At 49, Mykola Kobetiak has worked in the food industry for 22 years. Over 22 years, he’s worked his way up from a merchandiser to a factory director. In 2021, Mykola and his brother Oleksandr decided to build something of their own — a company that would specialize in waffle cones. Their friend, Oleh Miroshnychenko, joined them as the main investor — that’s how Nova Food was created. Today, the company employs a team of 40 Ukrainians and reached $1.6 million in annual revenue in 2024. Nova Food already exports to Poland, Lithuania, and Israel, and over the next few years plans to break into Bulgaria, the UK, and the U.S. This year, Nova Food was included in Next 250 Forbes Ukraine — a list of fast-growing small and medium-sized businesses expected to shape Ukraine’s economic growth in the coming years.

In more than three years of success, the founders of Nova Food haven’t been interviewed — until now. YBBP journalist Roksana Rublevska was the first to speak with Mykola Kobetiak about his journey to becoming a production leader, how waffle cones became an untapped opportunity in Ukraine, and how, in the middle of a war, he personally assembled the production lines that brought Nova Food to life.

Originally, you’re a programmer. Why did you choose not to pursue that career, especially since IT was considered a prestigious field in Ukraine back in the 2000s?

I graduated from Lviv Polytechnic and worked in my speciality for about a year and a half, but realized that the typical programmer’s career path didn’t really excite me. In 2003, I applied for a job at the Khlibprom Group because I was interested in the food industry. From the very beginning, I had an ambitious goal — I wanted to manage production. I started as a merchandiser. They gave me a company car, and I delivered fresh, warm bread to Fozzy supermarkets across Lviv. It might sound like an entry-level job, and it was, but I chose it deliberately because I wanted to understand how operations actually worked.

Within a year, I was promoted to assistant head of the confectionery department, and soon after, I headed it. Later, I was put in charge of launching a new production unit. I worked in logistics, inventory management, and sales, learning the ins and outs of production technology, and eventually transitioned into R&D. It was there that we created Ukraine’s first frozen bakery facility — an innovation that enabled supermarkets to bake bread on-site. Other producers later adopted this model. Altogether, it took me six years of hard work to become the director of one of Khlibprom’s plants.

Many people start at entry-level positions but never make it beyond middle management. How were you so confident at just 27 that you’d become a top executive?

When I became head of the production department, I had a rare opportunity to be in the company’s senior management meetings. The CEO was open to new ideas, even those that initially seemed unrealistic. I observed how the executives operated and learned a great deal about strategic thinking.

Proactive employees were given freedom. If you had an idea, you could turn it into a full business plan, present it to the finance team, and then pitch it to the CEO and commercial department. If the idea was viable, it was implemented. One of my projects was launching a production line for pastry fillings. I worked on it from documentation and cost calculations to test production and supply the main plant. Another project was our in-house dumpling production line. I calculated procurement volumes, selected equipment, and, together with technologists, developed recipes and launched our own dumpling production.

How long did you work at Khlibprom?

Nine years. And from my fourth year there, I was essentially managing large-scale projects in senior roles. For the last three years, I was the director of one of Khlibprom’s eight factories — a facility that produced confectionery goods like gingerbread, cakes, cookies, and bagels, and employed more than 2,000 people. When I took over, the plant was running at a loss. Together with the finance team, we calculated the profitability of each production unit and decided to close the unprofitable ones — the bakery and bagel divisions. That meant staff reductions, which was one of the hardest decisions of my career — a moment when you fully feel the weight of responsibility for both people and the business.

How many employees did you have to lay off, and how did you explain that decision?

We had to let go of about 25% of the workforce. I met with each person individually to explain the situation. I also promised that if the remaining production lines showed growth, we’d bring them back. Within two years, about 15% of those employees returned. We optimized expenses, automated and upgraded our equipment, and concentrated on product lines with the most growth potential. Thanks to those changes, the factory turned profitable in my very first year as director.

Why did you leave such a senior role to take what seemed like a lower position — becoming production director at another company?

In 2012, a company called Lutsk Foods, which owns the Runa brand, approached me with a very appealing offer with better pay, stronger benefits, and broader opportunities. I joined as production director and, within a year, was promoted to CEO, a position I held for another three years. But my family didn’t want to move to Lutsk. At the time, my daughter was still very young, and I could only come home to Lviv on weekends. I had the professional standing and experience to take a break, so I resigned and moved back home. About seven months later, I joined a waffle cone factory in Novoyavorivsk. Under my leadership, the plant grew from a single production line to eight. We invested in modern equipment, launched new product categories, optimized our operations, and built reliable sales channels. Over time, we expanded our product range, entered new markets, brought in partners, and reinvested our profits back into growth.

In 2021, you co-founded your own company. When did you know you were ready to take that step?

My brother Oleksandr and I had been thinking about it for quite some time. He started as a manager at Khlibprom, later became a financial director at several firms, and eventually launched his own business. We’ve always had a great deal of trust in each other. In my final year as production director, I began joining him on trips to European factories to check out equipment.

The company I was working for at the time had grown x6 under my management. That’s when I realized it was time to move forward — my brother and I were ready to start our own business.

But the company was founded as a team of three. Who is your third partner?

Our third partner is our childhood friend, Oleh. He had managed production operations for European manufacturers and also run his own business. When we told him about our idea, he said, “I want my money to work in production.” At this stage, our roles are well defined: Oleh is the main investor and strategist, while my brother and I focus on strategy, operations, and day-to-day production management. Our approach is that the company should not grow too rapidly. Technically, we could aim for 70% growth in 2025, but we’ve chosen to cap it at 50%. That decision enables us to maintain tight control over product quality and minimise risk.

How did you plan to stand out from existing competition?

While preparing financial reports for shareholders, I realized that there was a gap in the market. At that time, there were only two factories in Ukraine producing waffle cones. One was where I worked. The other produced cones exclusively for its own ice cream and didn’t sell to others. Essentially, there was a clear shortage in the market. At the same time, Ukraine’s demand for ice cream in cones was increasing by about 20% each year. There was also strong export potential — Ukrainian waffle cones cost several times less to produce than European ones. That’s when I knew it was time to open my own factory. We started the process at the end of 2021, purchasing equipment and setting up the production lines.

Did you need to develop or patent a unique recipe to stand out from your competitors?

This market operates under a completely different set of rules. If you want to become a supplier for major ice cream producers, your recipe has to match what they already use. These companies have their packaging already printed — any change to the ingredient list would mean they’d have to discard old stock and order new packaging, which would be incredibly expensive. So, cone makers don’t compete through special recipes. Instead, success depends on quality, price, and the ability to maintain stable, uninterrupted supply volumes.

If I start producing Coca-Cola, I’d be violating Coca-Cola’s rights because the recipe is identical. Is it different in your industry?

Yes. Coca-Cola is a brand with a patented formula — you can’t copy it without breaking the law. But in our industry, there’s no need to patent the recipe. Products like bread or waffle cones are basic goods. Our clients give us their product specifications, and we produce according to those requirements. The Ukrainian market is standardized — all cones are essentially the same. In Europe, though, recipes differ from factory to factory, so we adapt to the specific client.

Where is your production based now?

We have facilities with a total area of over 2,500 square metres. Our cone production line manufactures over 100 million cones per year.

Did Nova Food’s business model change after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine?

Yes, partially. In May 2022, we received Italian and German production equipment. But because of the war, European technicians refused to come to Ukraine to install it. We even offered them accommodation in Poland, daily transportation to the site, and even triple their standard fee, but they still declined because of safety concerns. Ukrainian contractors helped us assemble the first production line. And the second one, my brother and I built ourselves.

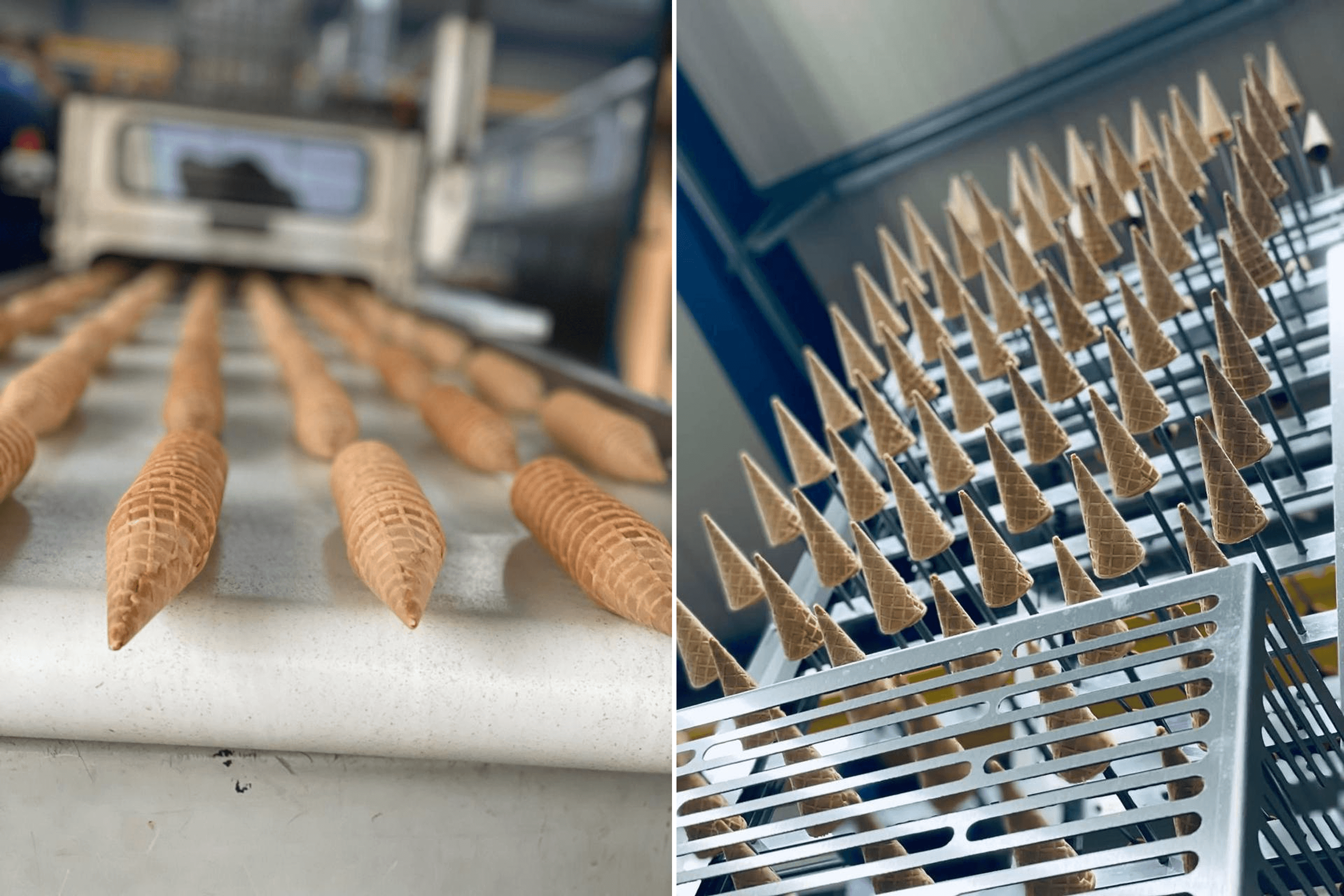

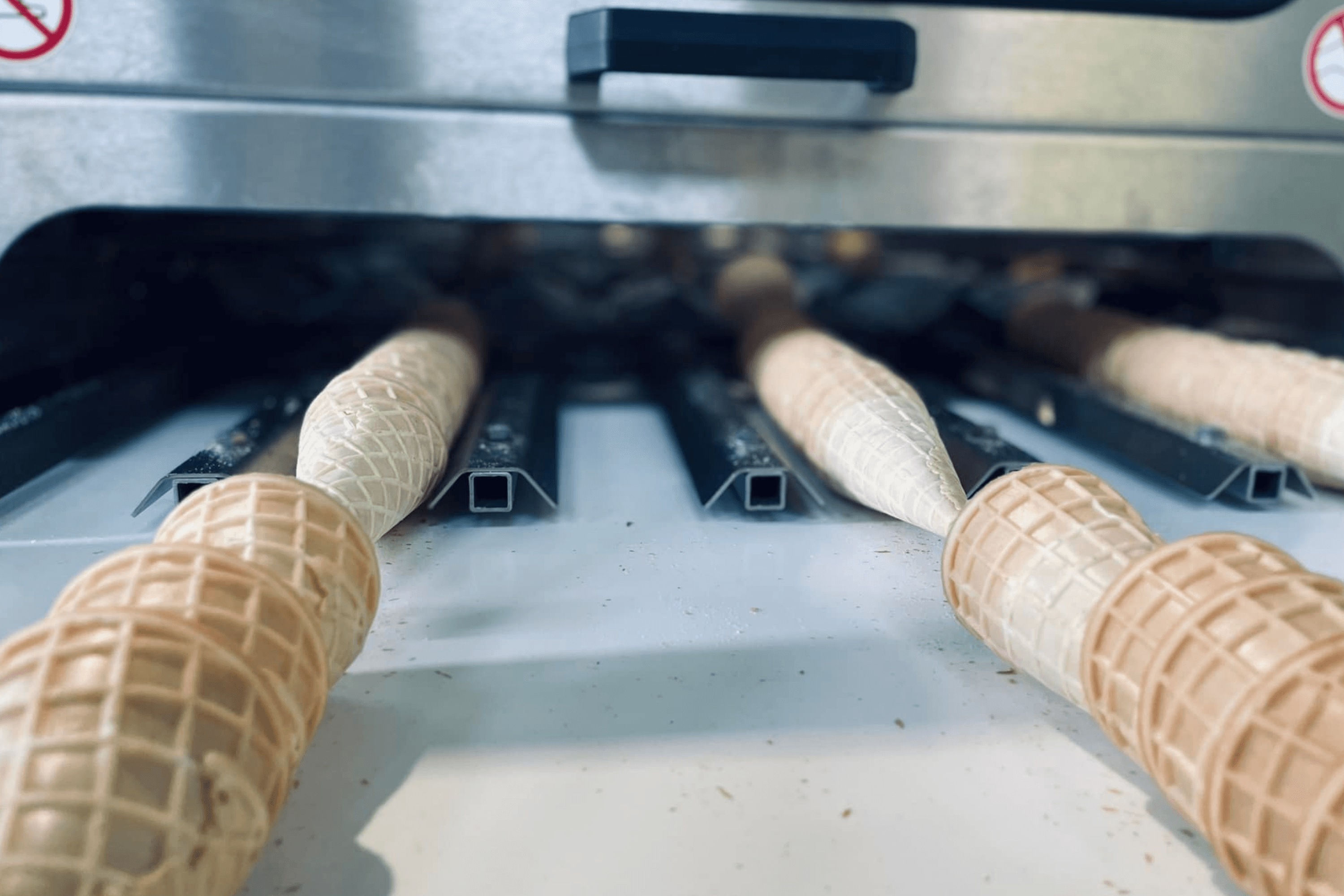

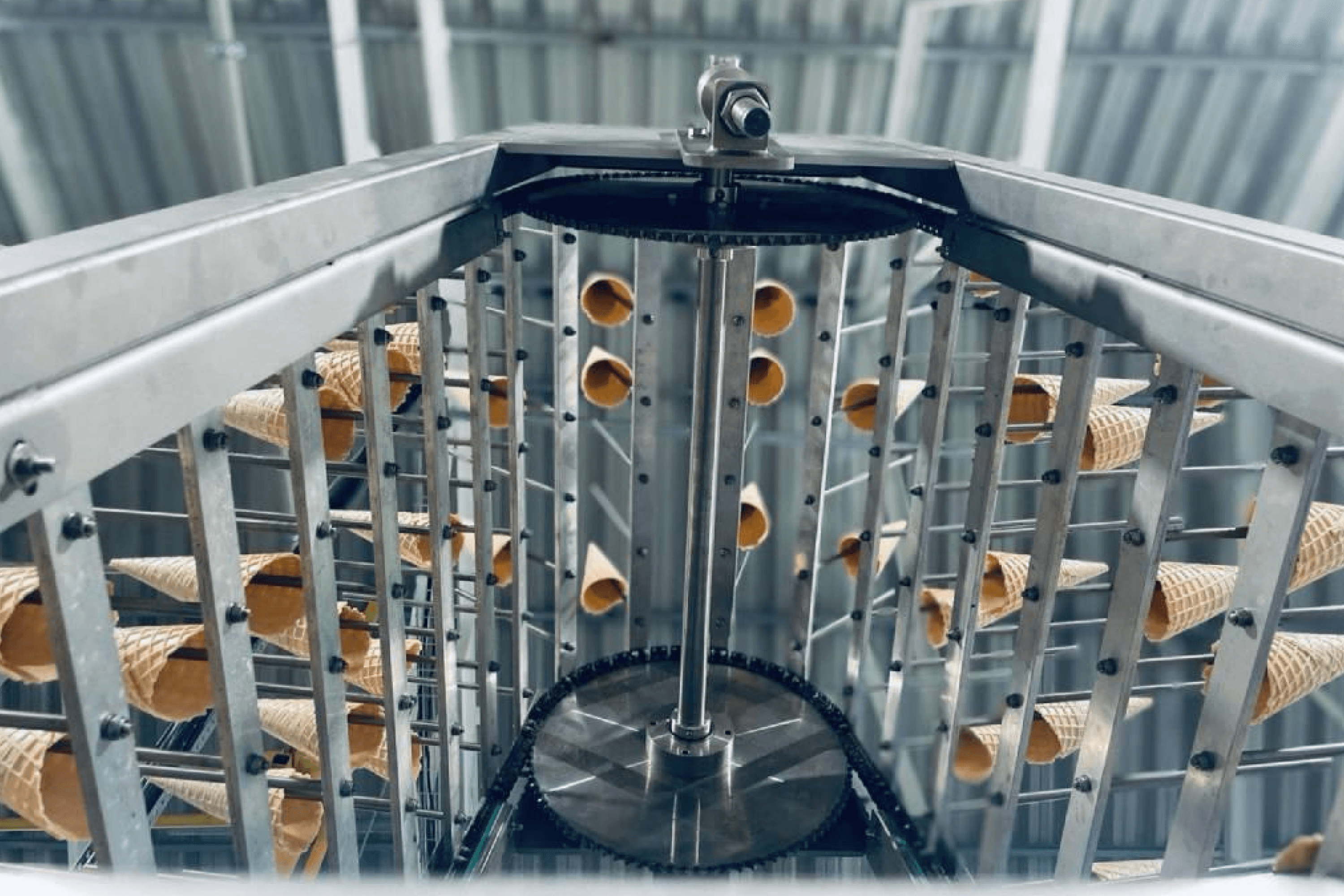

What does one of these production lines look like?

Picture the length of a nine-storey building — that’s how long the production line is. It handles the entire process from start to finish: mixing and feeding the dough, baking, shaping the cones, cooling, and packaging them.

How long did it take you to assemble the production line? And how did you know how to do it?

It took about six weeks. To put that in perspective, a German engineer familiar with the system could have done it in two weeks and spent another two training the staff. At first, I thought we wouldn’t manage without detailed instructions. But once I started, it all turned out to be quite logical: the boxes were numbered, and the assembly was step by step, just like building IKEA furniture. We launched our first production in early July 2022. Those were small batches that we sold to our first clients as test samples to build future partnerships. Because of that, in 2022, we made virtually no sales.

You began selling in January 2023. Who was your first client?

It was the company “Try Vedmedi” (“Three Bears”), to whom we’re very grateful for believing in us. They also have a plant in Poland under the Nordis brand. I already knew the market well and had open communication with top managers of all major ice cream producers, including this one. That helped me quickly reach out, present our facility, and propose a partnership that made sense for both sides. The details of the deal, of course, remain confidential.

At first, when we offered prices that were significantly lower than our competitors’, many clients were sceptical: “Something’s — are you cutting corners or hiding something?” There were even rumours that we were working off the books or avoiding taxes. But from day one, we committed to running a fully transparent business. The reason for our low prices was simple: we had a modern and efficient production line. Even at full capacity, it operates with fewer than 35 employees and requires much less energy and maintenance than competitors’ facilities. This directly affects production costs.

How much does your equipment cost? And how many production lines do you have now?

We’ve invested more than $1.5 million in production equipment. Additionally, we have machinery for producing children’s cookies and decorative ice cream elements. Every fall, we shut down the factory for about two weeks to replace consumable parts. The equipment is modern, durable, and built by leading manufacturers in Germany and Italy.

Did you take part in any government support programs?

Yes, we received ₴1.6 million from the state, but committed to contributing the same amount of our own funds. In total, we had ₴3.2 million to invest in additional equipment. In return, the government required us to hire five new employees, something we were planning to do anyway as the company grew, and to repay the funds through taxes and mandatory contributions. We met those obligations ahead of schedule. We’re also using the “Affordable Loans 5–7–9%” program from Oschadbank.

You mentioned that you considered moving production abroad but decided to stay in Ukraine. Why?

We already had one production line built, and most importantly, we wanted to stay and work in Ukraine. We wanted to create local jobs, contribute to the national budget, and do our part for the country’s future victory.

How did the European market respond to you?

When we first showcased our products at B2B trade fairs in Europe, we ran into some bias. At the time, many Europeans were cautious about working with Ukrainian companies; no one wanted to sign contracts because of the force majeure clause, which includes war. On top of that, we were a young company. European manufacturers generally don’t respond to initial emails or phone calls. If they don’t know you personally, you don’t get a chance. We packed boxes of our products and headed straight to the trade shows. Wherever ice cream producers were exhibiting, we’d walk up, introduce ourselves, and hand them samples to taste.

But you mentioned earlier that your cones aren’t really different from others. So what would make buyers choose your product if it’s basically the same, just less expensive?

What I meant is that the recipe and production process are the same. And that was precisely our goal — to make one that’s as good as the best on the market. For example, Romanian cones are cheaper, but their quality doesn’t match European standards. Our equipment is brand-new, which ensures a clean, consistent grid pattern, perfectly uniform size, and no white spots. These are the basic features that ice cream manufacturers notice immediately. Another crucial aspect is the edge of the cone — the part where it’s rolled. If that edge starts to curl outward, the cone is rejected as defective. Our cones don’t have that issue.

When the war began, did you expect to rely more on exports, since waffle cones aren’t exactly an essential product?

That was what we hoped, but the reality turned out to be more complicated. When the war started and we began actively supplying our products to ice cream factories in Europe, approaching ice cream manufacturers across Europe, many of them took a negotiation approach. They knew our options were limited and would be forced to accept almost any terms. When we named our prices, they’d respond, “No, we need them even lower.” From my experience, European companies can be quite conservative and very slow to open up to new partnerships. They were clearly assessing the risks, told us directly: “If you want to start working with us, we’re not talking about a 5% discount — we need at least 20–30%.” Naturally, we couldn’t agree to those terms. So we decided to focus on the domestic market and looked for mutually beneficial partnerships instead.

So, when did you first enter international markets, and what product did you start with?

That happened in 2023. It wasn’t with our cones, though. It was with brownie crumbs — crushed cookies used as toppings for ice cream in cups or cones. Our first international client was a large Lithuanian company, Dione. It all started at a trade fair: my brother Oleksandr was there, handing out small presentation boxes with samples of our product. The Dione team reached out afterward. They already offered a similar topping and sent us their specifications. We reworked our recipe to match their ingredient list, produced a test batch, and sent it for approval — a standard practice for us to make sure everything aligns with the client’s production technology. After a successful start with the Lithuanian company, we expanded to Poland at the beginning of 2024. In Poland, we currently operate only through distributors serving the HoReCa sector. We haven’t started direct factory partnerships yet.

Is it true that your export prices are sometimes much lower than what you charge in Ukraine?

That’s right. However, considering that export operations provide us with additional financial benefits, like VAT exemption, it still works out and helps balance out the lower selling price. In addition, our foreign partners pay upfront, without delays, whereas many domestic clients tend to take the product first and pay later.

Are there any changes in EU food regulations that make it difficult to enter European markets?

Not really. The process is actually quite straightforward. Last year, we were audited by a German certification body, and this year by a Belgian one. We received an international ISO 22000 certificate confirming our compliance with global food safety standards. This certification is also mandatory in Ukraine.

Which other markets are you active in besides Poland and Lithuania?

We’re also present in Israel, where we operate through a distributor who mainly works in the HoReCa sector. In addition to supplying him with cones for restaurants and cafés, we also produce B2C versions, package them in boxes, and he sells them in supermarkets. I can’t say exactly where the products end up — it could be just Israel, or the distributor may resell them elsewhere. He’s not required to report that to us. This product has its own specifics, as each batch must be accompanied by a kosher certificate.

Which market segments do you currently target?

We divide our business into four segments. The first — and our main one — is B2B partnerships with ice cream manufacturers. Pricing in this segment depends on order size, payment terms, the history of collaboration, and plans. We set the terms for an entire season so both sides can plan production and logistics in advance. The second segment includes distributors in both domestic and foreign markets that operate in the HoReCa sector. The third is contract manufacturing, where we produce cones under other companies’ private labels. The fourth segment, while still small in total sales, has the greatest potential for future growth — B2C, where we sell finished products under our own brand through national retail chains. Prices in this segment are based on product margins and marketing costs.

We entered the B2C market for the first time this year with a family box of cones sold in Fozzy supermarkets. Essentially, we’re introducing Ukrainian shoppers to a model common in Europe and North America — people buy cones separately, add their own ice cream, sauces, sprinkles, or berries, and make it a family ritual. Buying pre-filled cones costs more. There’s a catch, though: in B2C, payments usually come in only after six months. That’s expected, but companies need to plan for it. We haven’t yet entered major chains like ATB, which operates more than 1,500 stores. First, we want to fine-tune the process. Large chains can create sudden spikes in demand that are hard to handle, since it’s not just about making cones — you also need to wrap, pack, label, palletize, and ship them efficiently.

What’s the current split between your B2B and B2C sales? And how much of your production goes to the domestic market versus exports?

B2C makes up 1% — about 150 supermarkets — and we independently invested in 150 display stands for our product in those stores. The remaining 99% is B2B. Around 85% of our production serves the Ukrainian market, while roughly 15% goes to export.

Tell us how you plan to enter the U.S. market.

That opportunity actually began through a Stanford University program for Ukrainian entrepreneurs called Stanford Ignite Ukraine. My brother met potential partners there who were interested in a very small cone, just 60 mm. They told us they’re ready to buy as many as we can make. However, our production line is designed for cones ranging from 85 to 160 mm. This puts us in a position where we have to decide whether to invest in a new line or not. The U.S. market is enormous, and we already have interested partners, but we’re limited by technology. Even so, we’re leaning toward taking the leap and giving it a try.

Why are those few centimetres so important for the U.S. market?

It’s very simple: every additional 2 centimetres of the cone increases the weight of the ice cream. American producers sell small portions at high prices. If they make the cone larger, they have to add extra ice cream, and that’s not profitable for them. In the U.S., everything is calculated down to the millimetre.

Which new markets, besides the U.S., are you looking at?

We’ve received inquiries from Bulgaria, Latvia, Moldova, and several Middle Eastern countries. I also recently visited the United Kingdom. We were invited as part of a delegation from local governments: deputies and mayors from western Ukrainian cities to attend the Royal Norfolk Show. It is the biggest agricultural exhibition in Norfolk. It was an honour to meet His Royal Highness Prince Edward there. The British side has promised to invite us to future local B2B events where we can present our products, introduce us to representatives of regional chambers of commerce across the UK, and help us connect with British businesses.

And what’s unique about the product for the UK market?

British consumers prefer cones with a rich, buttery flavour, which means using real butter. But that automatically shortens the shelf life. Our cones can normally be stored for up to two years. This raises logistics questions: how to deliver the product to the UK, how long it can be stored, and how to handle potential returns. It’s an appealing but complex market, and it can’t be conquered quickly. Still, we’re in the process now — developing a strategy to enter it step by step.