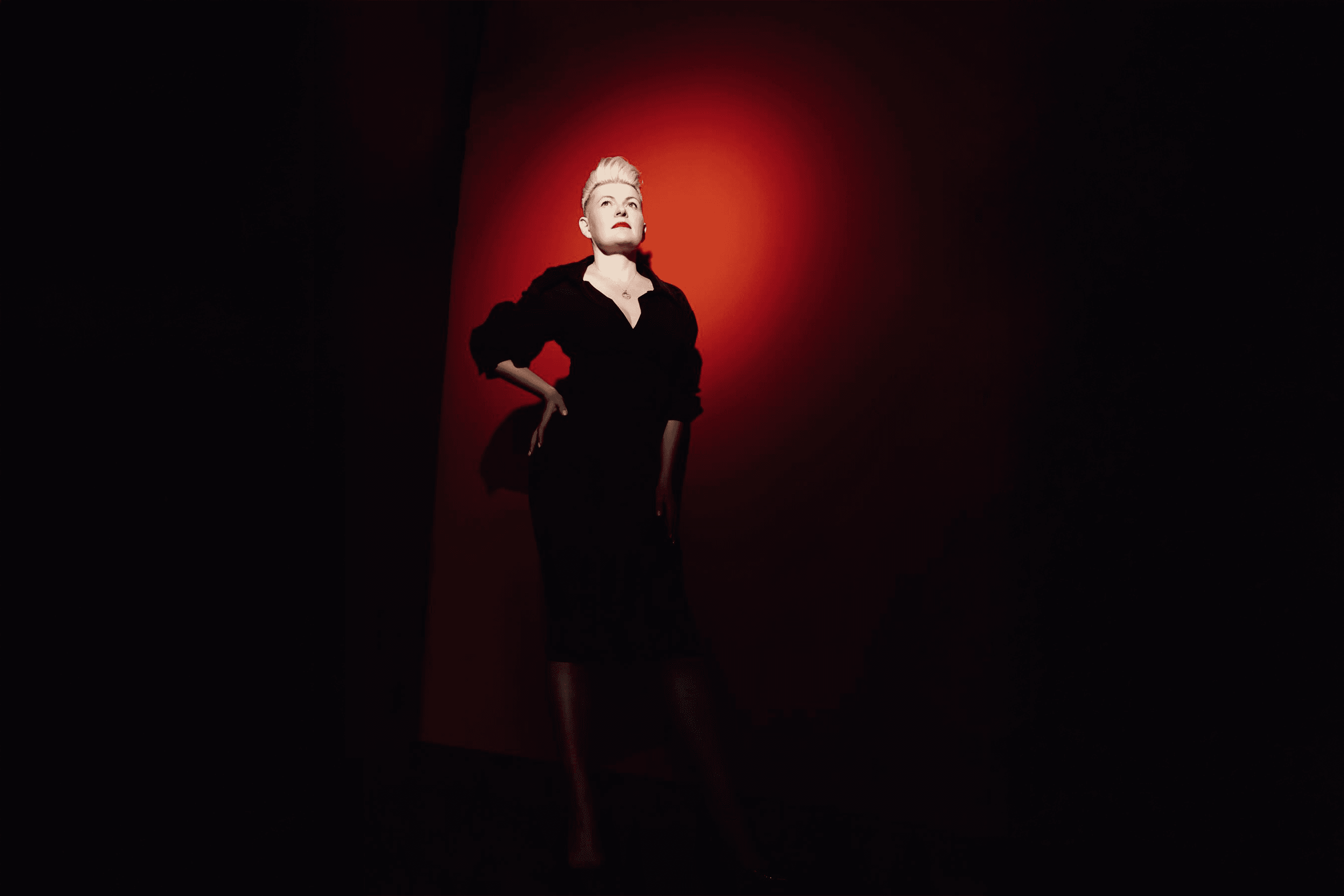

Forty-six-year-old Alla Lopatkina from the Ivano-Frankivsk region has never been afraid to take risks. At just 19, she turned her boyfriend’s bar into a restaurant and a few years later, after receiving her green card, she set out for the United States. In Chicago, she worked as a cashier, an assistant to a bank advisor, and even as deputy vice-president of the holiday decorations corporation, Santa’s Best. In 2009, she and her husband launched RoadLynx Inc., a logistics firm in the U.S., which went bankrupt during the 2011 financial crisis.

Alla did not give up: she advanced to Chief Operating Officer in the logistics sector, secured a bank loan of $260,000, bought a stake in the company where she was employed, and in 2019 established Nortia Logistics, growing it into a business with annual revenues of over $50 million in 2021.

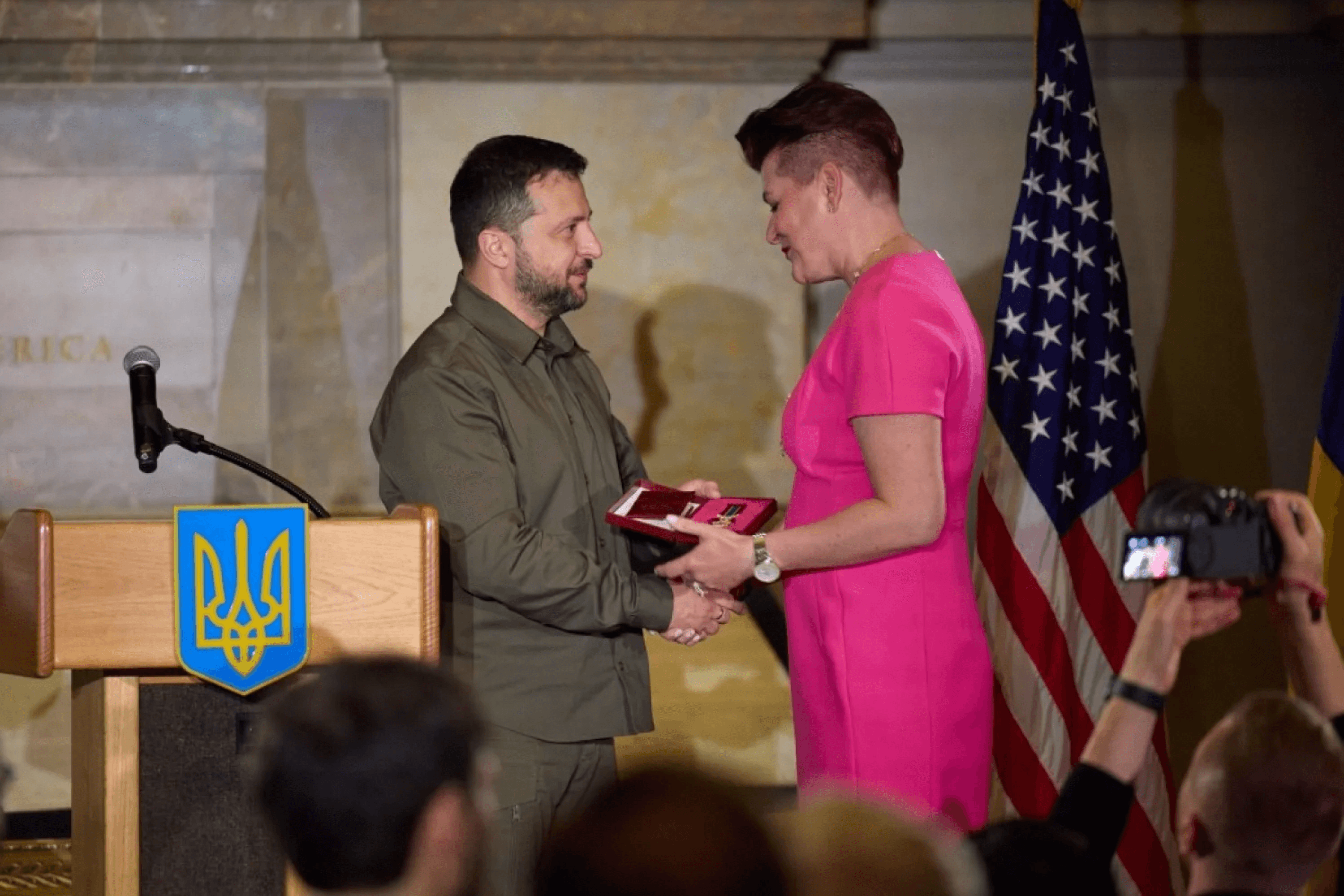

Since the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Lopatkina has been actively supporting the Armed Forces of Ukraine: she established the Ukrainian Resistance Foundation and financed the purchase of medical equipment and vehicles. In 2023, she sponsored the Ukrainian Phoenix installation at the Burning Man festival, a symbol of resilience. That same year, she was awarded the Cross of Ivan Mazepa by President Volodymyr Zelenskyy.

Today, while navigating a divorce and mounting business pressures, Lopatkina continues to volunteer, lead cultural projects, advocate for Ukraine before U.S. congressmen, and fight to keep her company stable through a new crisis. This is her story.

1

Alla Lopatkina was born in 1979 in Tysmenytsia, a small town in the Ivano-Frankivsk region and by the age of 11, she already sensed that the place felt too small for her ambitions.

Her childhood unfolded during the final years of the Soviet Union and the turbulent 1990s, when Ukraine was going through an economic crisis. She grew up in a family of three children: Alla and her two brothers. They lived modestly: her mother was a hairdresser and her stepfather was a truck driver. From an early age, Lopatkina showed an interest in business, which led her to pursue studies in economics at a university in Ivano-Frankivsk.

At 19, Lopatkina was dating a guy who owned a small bar near the railway station. She saw potential in it to become a restaurant. Together, she and her boyfriend took on the renovations themselves. Along the way, she learned how to plaster and paint walls, cut tiles, and design a functional space. The bar soon transformed into a restaurant and started generating steady income. The couple reinvested their earnings into the business, expanding the menu and upgrading equipment.

Alla’s workdays were close to a marathon, often stretching to 14 hours. She was the bookkeeper, buyer, cook, bartender, and manager all at once. She hauled sacks of potatoes and meat, made dumplings, fried cutlets, and served guests. It was difficult and exhausting, but she found joy in seeing the results, knowing they were achieved through her own effort.

This experience shaped one of her guiding principles: “Even as a leader, I will never stand aside and watch others do the hard work. When necessary, I will work shoulder to shoulder with the team.”

In 1999, Lopatkina’s stepfather won the U.S. green card lottery. Her 21st birthday was still six months away, which meant she was eligible under U.S. law to immigrate with her parents and younger brothers. She had no plans to leave Ukraine permanently, but she was the only one in the family who spoke English, so she felt a responsibility. Her plan was straightforward: take a leave of absence from university, spend six months in the U.S. helping her family settle, and then return to Ivano-Frankivsk to her studies, her business, and her boyfriend.

In December 1999, Alla came to Chicago with $200 in her pocket and followed through with her plan. But when only a few weeks remained before her return to Ukraine, she found herself hesitating. She remembers sitting on the windowsill of her rented apartment in Chicago, clutching her return plane ticket in her hands. She cried from exhaustion and helplessness. Chicago felt like a city of opportunities, a place where she felt the freedom, while back in Ivano-Frankivsk, what awaited her was another 14-hour workday, complete chaos, and a failing relationship.

“At one point, I thought: if I managed to build something in a country that offered no real path to success, then here, in the United States, I could realize my potential fully. Yes, it would be hard. But it would be easier to work within a system that rewards effort instead of obstructing it,” she says, recalling her decision to remain in Chicago.

Lopatkina’s first job in the United States was as a cashier at a Ukrainian bakery, which was a community hub for Ukrainians. The pay was just $5 an hour, but it gave her her first English-language experience working with customers. At the same time, she attended free language courses at a local college and began building a family: at the bakery, Alla met her future husband, Oleksii, who had come to Chicago from the Kharkiv region. He worked as a long-haul truck driver but spoke no English, so Alla took on most of the dispatching and administrative tasks: planning routes, managing paperwork, and even securing loads.

Within a year, she moved on to a cashier position at a bank and was soon promoted to personal banker. For many immigrants, this would have been the end goal. For Alla, it was just the beginning.

In 2001, Lopatkina became an assistant to a bank advisor. Within just a few months, she passed the exams for two of the industry’s most demanding licences: stockbroker and financial consultant. She studied for them on her own while working 16-hour days, six days a week.

2

In 2007, Alla made a sharp career shift, joining Santa’s Best, a U.S. manufacturer and importer of Christmas decorations. She became assistant to the Vice-President of Sales and, for the first time, was working directly with major American retailers.

In this role, she went through the full lifecycle of holiday products: from R&D and product selection to overseeing production in China and coordinating delivery to retail chains. The position required frequent trips to Hong Kong, negotiations, and team management across different countries. It was here that Alla developed the ability to handle large volumes of information and manage multiple processes at once.

At Santa’s Best, Alla earned about $50,000 per year. This was hardly enough even to rent her own place, so she had to look for roommates. She and her husband also sent part of their income back to Ukraine to support his children from a previous marriage.

In 2009, the couple registered their own logistics company, RoadLynx Inc., specializing in freight transport and cargo consolidation. The initial investments were small, but they had other strengths: Oleksii’s industry experience and knowledge, and Alla’s organizational, language, and communication skills. She took charge of finding contracts, negotiating with brokers, and optimizing processes. Their efforts paid off: within a short time, the fleet grew to 12 trucks, used, but still an impressive milestone for an immigrant-owned business.

At that time, the U.S. transportation market operated through intermediaries, and small newcomer companies had to fight to earn trust. Alla soon realized that in logistics, trucks were just tools, the true value lay in people.

However, 2011 brought a crisis to the entire trucking industry. Freight rates plummeted, trucks outnumbered available cargo, and small carriers were hit the hardest. For Lopatkina, it marked a turning point both personally and professionally. She had warned Oleksii that the market wasn’t ready for expansion, but his drive to scale up exceeded the market’s capacity. The business collapsed, and the couple lost about $200,000 of their joint savings. That same year, they had to sell off the fleet to recoup what they could, keeping just one truck so Oleksii could return to long-haul driving.

At the same time, Alla was dealing with preparing documents for Oleksii’s children’s immigration to the United States. His daughter was 20 and his son — 18. She knew this opportunity might never come again, so she did everything she could to help.

“If you can do at least something to improve someone’s life, but you don’t do it, you will never forgive yourself later,” Alla believes.

In the end, everything worked out: Oleksii’s children joined them in the United States. They all crammed together — eight people in a small two-bedroom apartment in Chicago: Alla, her parents and brothers, Oleksii, and his children.

After shutting down their own company, Alla took a job as a dispatcher with a Polish logistics firm. The pay was modest at first, but she quickly proved herself, earning a raise and expanded responsibilities within a few months. From 2012 to 2015, she worked as general manager at DDM Logistics, while also finding freight contracts for her husband. In 2012, the couple also founded Nortia Logistics, a consultancy providing operational and strategic support to logistics companies. From then on, much of Alla’s work was structured as contracts under Nortia Logistics.

By mid-2015, she had mastered every aspect of the business’s internal operations. One client, AmTrans Expedite, invited her to lead a project and implement the same system within their company, integrating both road and rail freight. Alla accepted the role and became COO, increasing her annual income to $130,000. Her schedule was relentless: six days a week, 12 to 14 hours a day.

Lopatkina candidly admits that her marriage was in many ways shaped by her “rescuer complex” and an overdeveloped sense of responsibility for others, which roots in childhood trauma. She recognizes that the relationship offered little real support. Instead, she was met with criticism and the persistent expectation that she should “always do more.” In her own words: “I know how to move myself away from the place where it hurts, to the place where I feel comfortable — and that place is my work.”

3

In 2017, Alla became a mother to a son, Maksym. On the morning of his birthday, she was still at work, onboarding a new employee. For the first eight months after, she continued working from the office with her baby beside her, hiring a nanny only once he started crawling. Around the same time, her husband stopped working, explaining it by fatigue, depression, and resentment that his wife was not building the business together with him.

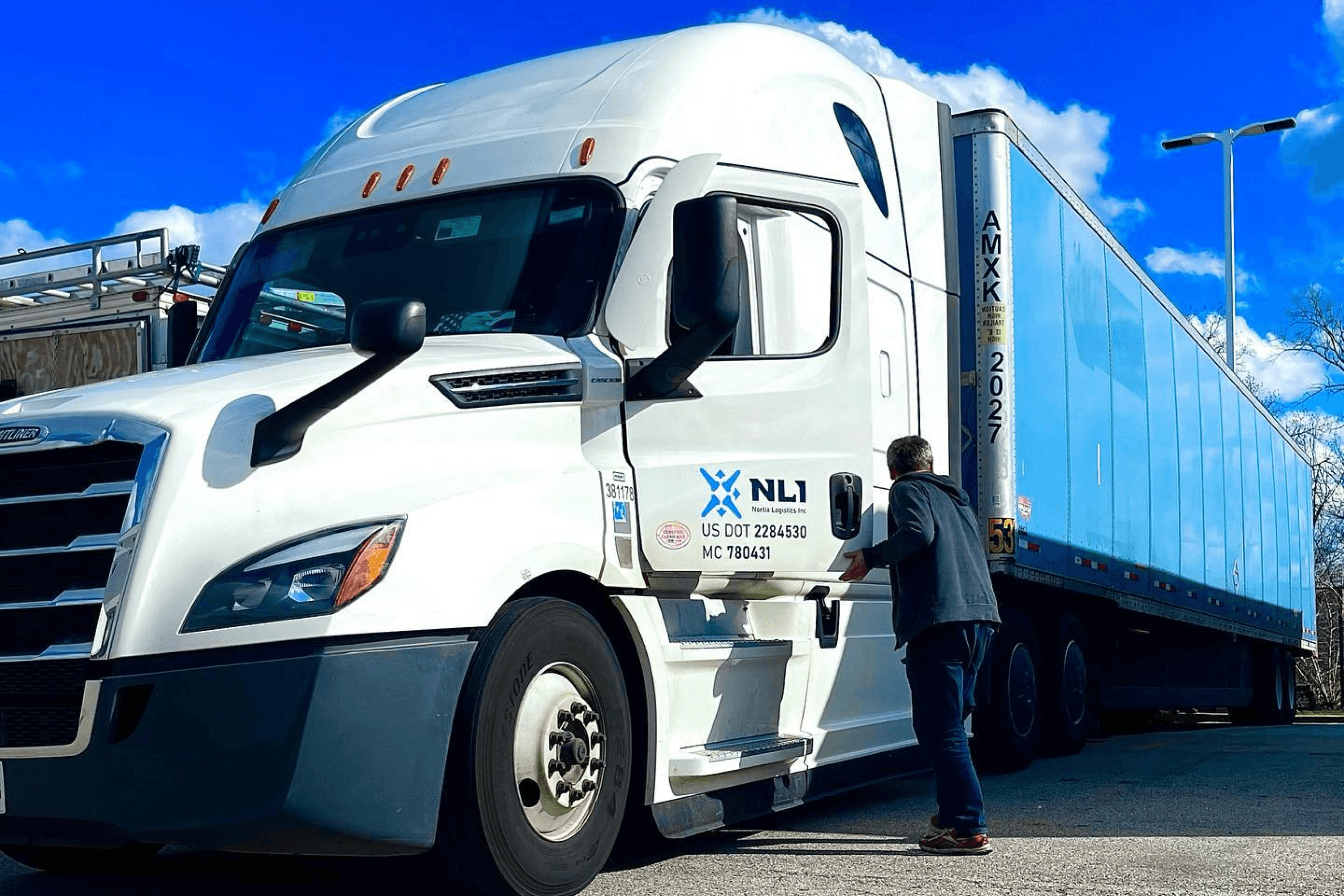

In 2019, the company where Lopatkina was employed merged with a private equity fund, triggering a wave of restructuring. Several departments were closed, particularly those whose performance depended on key employees. One of them was the department managed by Alla: the entire operating system and contacts were concentrated around her. Lopatkina proposed an alternative: to buy out the department and turn it into her own venture. That September, Nortia Logistics made the transition from a consulting service for logistics firms into a full-fledged carrier with its own assets.

To make her plan a reality, Alla got a loan of $260,000 and took on roughly $500,000 in the company’s truck-related debt, including lease payments for the next two years. At that time, her annual income was $200,000, with nearly no personal savings — she had purchased a home shortly before.

Within only two weeks, Alla launched the business. This was how the new Nortia Logistics was born. The company quickly became profitable, generating $5 million in revenue in its first three months and $26 million in its first year. Alla even managed to pay off the remaining $180,000 of the loan ahead of schedule. She built a business model that combined intermodal shipping — blending rail and trucking — with cargo consolidation, grouping shipments from multiple clients into a single container or truck. This approach allowed for more efficient use of equipment and capacity, enabling higher volumes without added resources. “We achieve greater output with fewer resources, while preserving additional margin,” Alla explains.

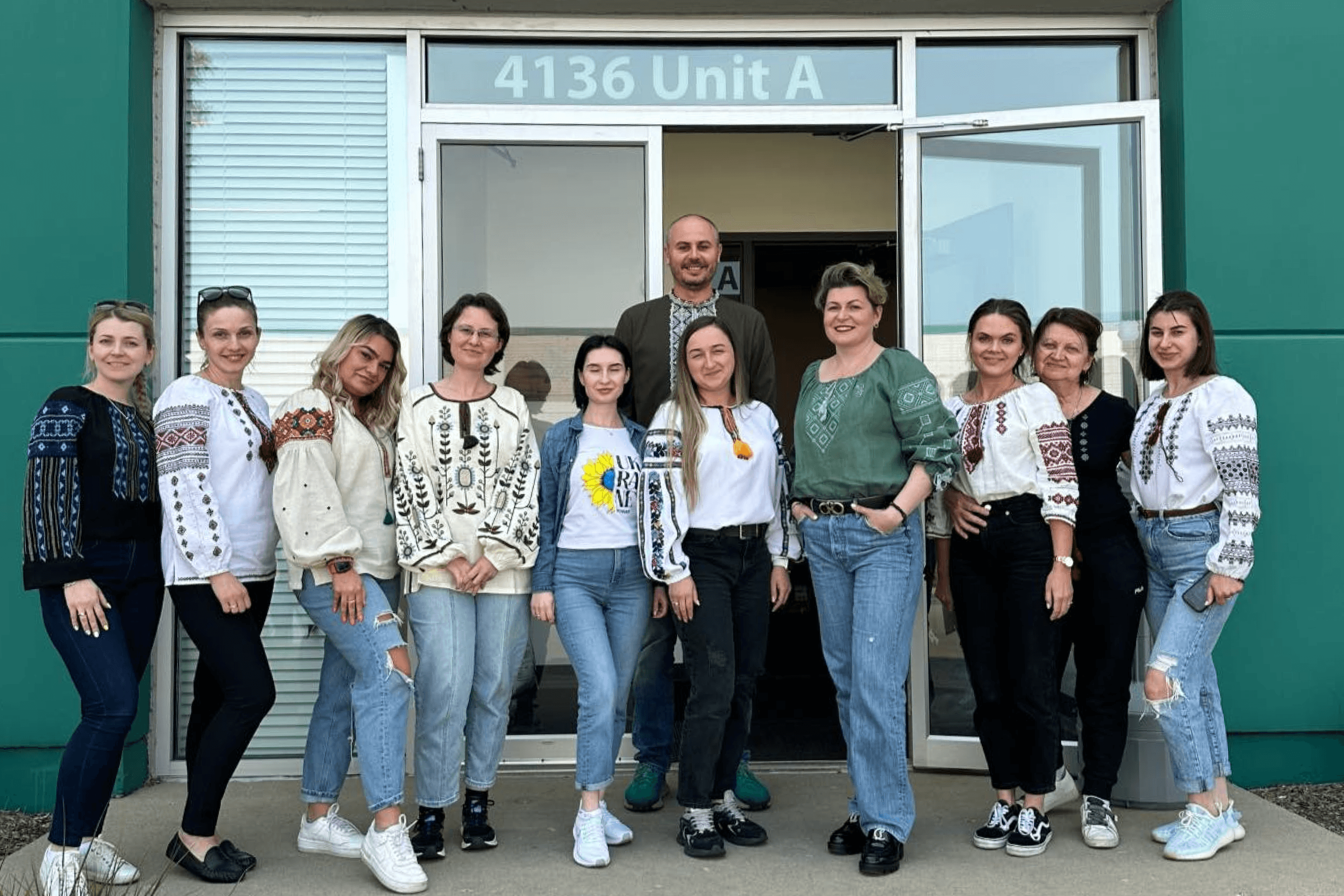

Her company employed around 100 office and warehouse staff and 60 drivers, the majority of them originally from Ukraine, Poland, Jordan, Mexico, and the Philippines.

In 2020, the coronavirus pandemic triggered a global financial crisis. The world stock market collapsed, but this worked in Alla’s favour: she was able to purchase trucks, trailers, forklifts, and industrial real estate at low prices.

“If I had to choose again, I would start a business during a crisis,” she says with confidence.

In 2021, during the post-COVID boom, Alla’s company revenues reached $53 million, and in 2022 climbed to $56 million with a profit margin of 30%. This is a high indicator for the logistics business.

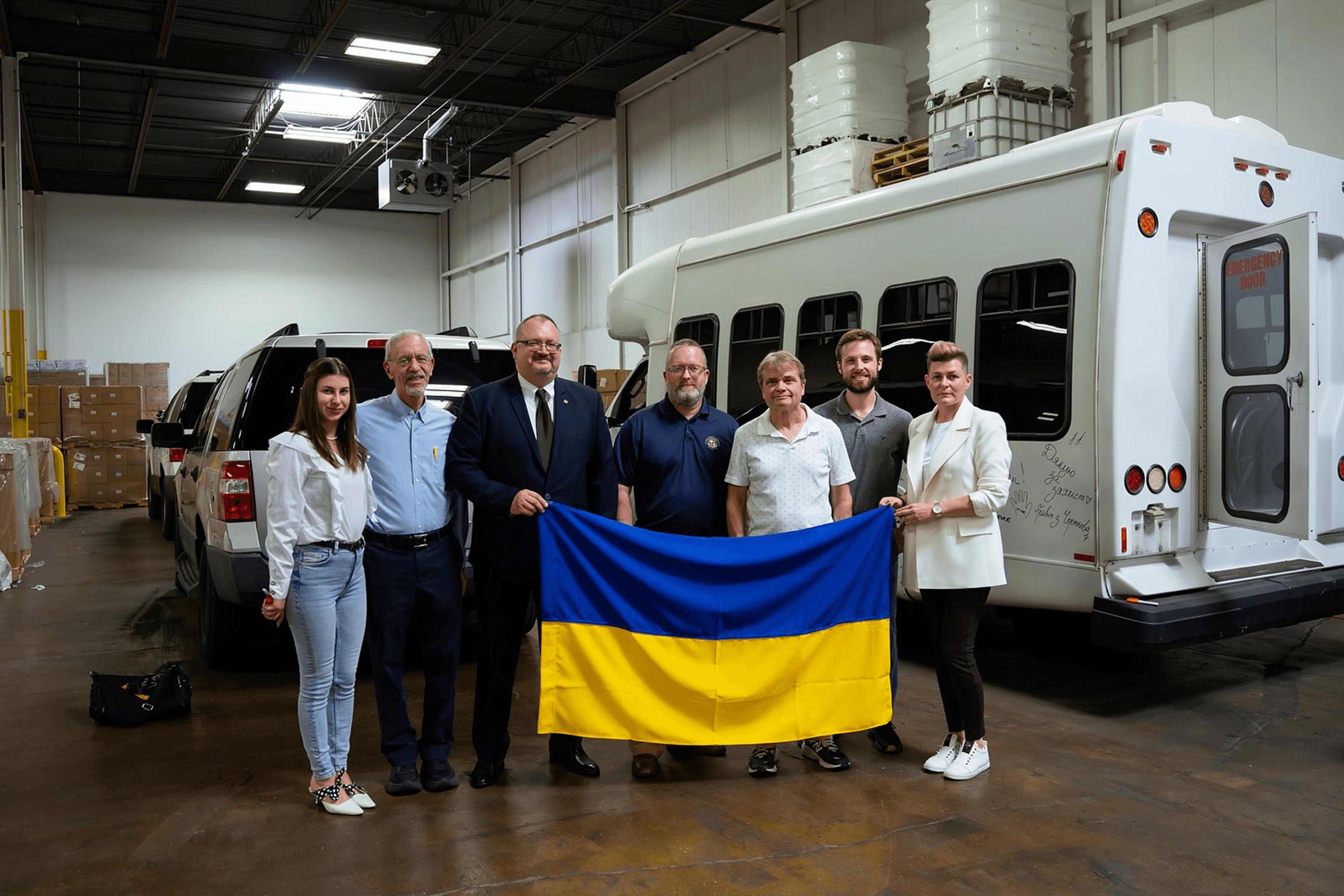

In February 2022, using her company as its base, Alla launched the Ukrainian Resistance Foundation and started directing part of her profits to support Ukraine funding aid for the military, families with children with disabilities, seniors living alone, orphanages, and animal shelters.

4

The start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine deeply affected Alla. For the first time in 24 years, she returned to Ukraine and fully switched to volunteer work. In 2023, she travelled to Kramatorsk and Toretsk. And her planned trip to Bakhmut was cancelled when access for civilians and journalists was shut down due to heavy fighting.

For Alla, the journey home was about reconnecting with her country and reassuring herself that she still belonged. The most daunting moment came as her train pulled into Kyiv’s central station. “I was afraid I would step onto the platform in Kyiv and feel like a tourist. But that never happened — and I was happy,” she recalls.

To deliver aid to Ukraine, Alla established cooperation with international donors who provided medical equipment and vehicles. Her foundation managed the logistics — designing routes, handling paperwork, and distributing supplies. Some shipments were coordinated through Serhiy Prytula’s foundation at the time, it was almost the only Ukrainian organization able to legally process such deliveries. Over three and a half years of full-scale war, Lopatkina’s foundation has spent more than $4 million in support of Ukraine.

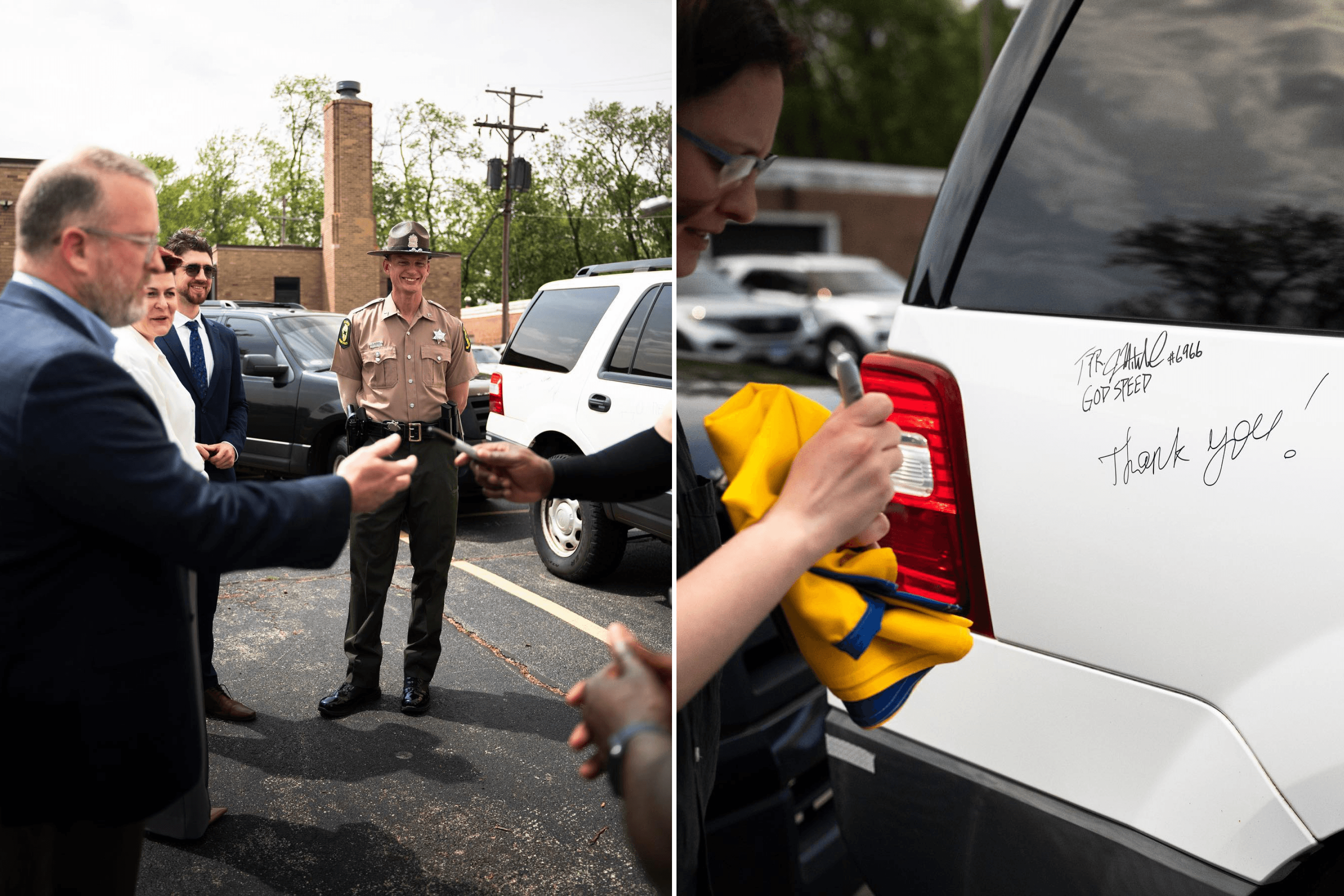

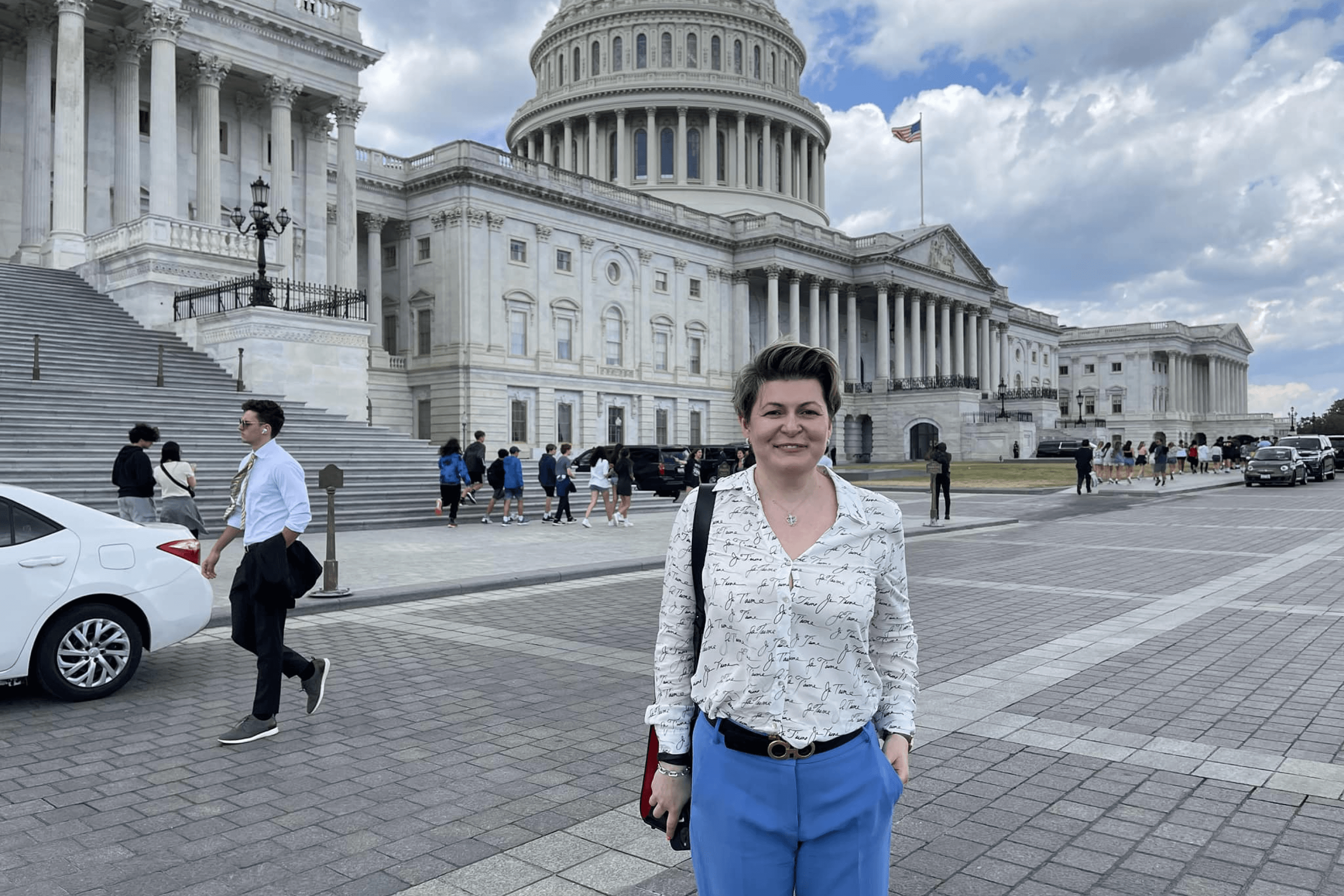

Alla also advocates for Ukraine’s interests in the United States. She regularly meets with senators and members of Congress to explain the context of the war and encourage legislative action. Lopatkina’s team promotes resolutions to ensure international recognition of the Holodomor as genocide, documenting Russia’s abduction of Ukrainian children, designating the Wagner Group as a terrorist organization, and tightening sanctions against Russia.

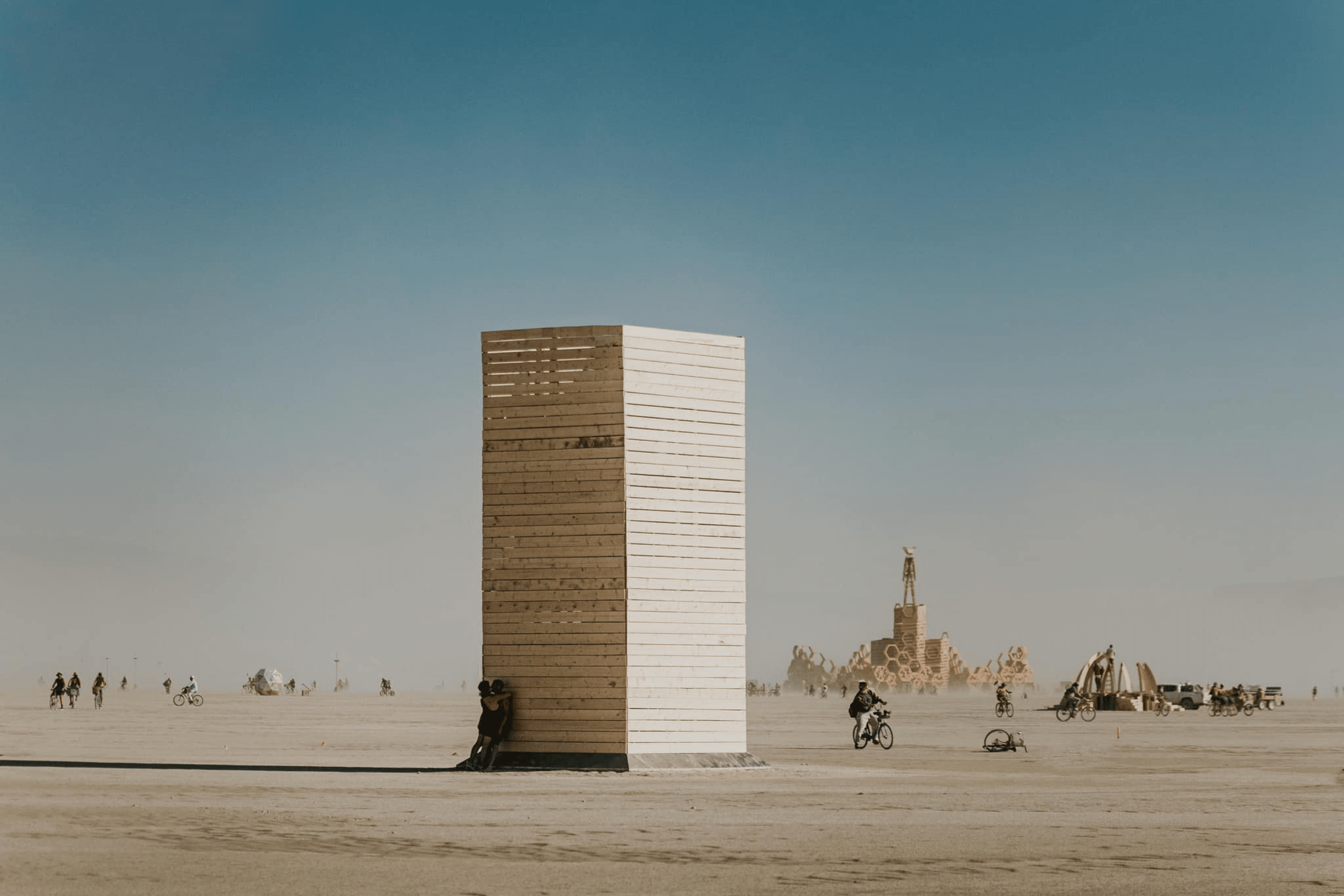

In 2023, Alla organized and funded the Ukrainian installation Phoenix at the Burning Man festival. The idea of bringing Ukrainian art to the festival had been proposed to her a year earlier by Vitaliy Deynega, Deputy Minister of Defence for Digital Development and founder of the Come Back Alive foundation.

Alla recalls: it was a real challenge. She had never been to Burning Man, considers herself an extreme introvert, yet has always been fascinated by art. The installation alone cost her $156,000. In addition, she covered expenses for logistics and setting up the Ukrainian camp, but she does not disclose those amounts.

That same year, Lopatkina also organized a major C Ukraine pop-up event in the very centre of Chicago, bringing together a hundred Ukrainian brands. The event cost around $250,000. Although it did not generate profit, part of the expenses was offset through sales. The remaining goods were transferred to Alla’s foundation, with the proceeds directed to the Armed Forces of Ukraine. After the success of C Ukraine, similar pop-ups began to appear in various cities across the United States. For Alla, the message was clear: “If Ukrainians can work under wartime conditions, it proves they can succeed under any circumstances.”

5

Alla says that in 2022, she realized that Ukraine needed her. This deepened the crisis in her marriage. For her, meaning and the desire to help mattered most, while for her husband, it was financial security. At a family gathering, Oleksii once joked, “Sometime this year, my wife was kidnapped and replaced with this one. And it’s uncomfortable. Take her back and return the real one.” Lopatkina admits there was a grain of truth in his words, even if they were meant as a joke. Still, she had no intention of becoming the “comfortable” version.

In 2025, she filed for divorce. The process has been long and painful. Oleksii does not want the separation as he depends financially on Alla’s income. “My husband’s position is: ‘I was the homemaker, I supported her. Now I deserve half of everything she earned.’ He’s even demanding spousal support from me,” Alla explains.

Her greatest source of support has been her eight-year-old son, Maksym. “We have an unusually close, open relationship — exactly the kind I always wanted to have with a child,” she says.

But with so much of her energy devoted to volunteering since the start of the full-scale invasion, her business began to suffer. She handed over her responsibilities to her team, confident they could manage after years of experience with the company. In 2024, revenue fell to $36 million.

The revenue drop, combined with an overall decline in shipping demand related to the ongoing post-COVID crisis, forced Alla to cut half of her workforce. Today, her company employs 60 people. She notes that she kept staff on the payroll far longer than her competitors, reluctant to leave them without jobs.

People have always meant a lot to Alla, and she has never treated them as just a resource. She has invested in her staff, promoting those who excelled, and in return gained fresh perspectives on how to improve processes. Having “Nortia” listed on a résumé became a mark of distinction within the logistics sector. “We know you would never keep someone on the job who wasn’t delivering quality work,” Alla recalls a colleague from the same industry saying.

To strengthen her leadership skills and improve the company’s operations, Alla decided to continue her education. In December 2025, she is to receive an Executive MBA degree from the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University. The program covers all key aspects of business management, from finance and accounting to operations and strategic marketing.

As much as in business and volunteering, in her studies, the main value for Alla has been communication. She has connected with professionals from different business environments and has had the opportunity to gain experience and see her own from a new perspective.

Looking ahead to next year, once restructuring is complete, Nortia Logistics plans to enter a new stage of development: Alla wants to expand its geography and integrate advanced IT solutions — a step toward offering a more comprehensive service that combines traditional logistics with innovative digital tools.

At the same time, Lopatkina is considering another sharp turn: to move into the legal sector with a focus on the defence industry. This involves work on the regulation of arms trade and dual-use goods.