Ladó Agency is now among New York’s most dynamic PR firms, partnering with brands across Ukraine, the U.S., and Europe. Its founder, Armenian Lado Kostandian, is a true example of how one can fight for their passion. Born in Poltava, a provincial city in central Ukraine, Lado dreamed of the stage from a young age, resisting his father’s strict belief that creativity was a disgrace for a “real man.” Eventually, Lado grew to be Poltava’s leading event manager.

At 19, he moved to Kyiv, where he founded Ladó Agency, soon working with global giants like H&M, Guerlain, Givenchy, and L’Oréal Paris. Since 2024, Lado has been based in New York. His agency helps Ukrainian brands break into one of the world’s toughest markets.

This is his story.

1

Lado’s parents grew up in the mountain town of Alaverdi in Armenia, and had been school friends. Life, however, took them on different paths for a time. In the late 1980s, Lado’s grandfather, a professional chef, moved to Ukraine with his three sons. In Poltava, he opened Café Caucasus, an authentic slice of Armenia in the heart of Ukraine, quickly earning fame for its traditional meat dishes. Lado’s father grew up, returned to Armenia for his future wife, and brought her back to Poltava. There in 2005, he established a transportation company that operated throughout the entire Poltava region, with a fleet of nearly one hundred buses and minibuses, half of which were owned by Lado’s father. Around that time, he got married. In 1996, Lado was born, named in honour of his grandfather.

The Kostandian was a traditional family, reflecting the Armenian community’s conventional view of “male” pursuits — business, technology, crafts. Creativity was not part of that list. But Lado’s mother, recognizing his natural expressiveness, insisted that her son belonged on stage. For their conservative relatives, it was an unconventional choice. Still, at the age of 7, Lado enrolled in the theatre department at the Youth Academy of Arts. There, he studied art history, choreography, puppetry, rhythmics, and acting. The experience gave him a profound appreciation of art, complemented by knowledge of the Armenian language and the national traditions of both his Armenian roots and Ukrainian upbringing.

Lado’s childhood was full of contrasts. He grew up as his mother’s favourite. His father was more interested in gambling than in the family, and gradually gambled away cars from his own business at the casino. To keep the household afloat, Lado’s mother began working as a cosmetologist. Eventually, the marriage collapsed, and his parents divorced when Lado was 15. That was the moment he first realized he would not stay in Poltava. He was drawn to Kyiv and the world of television. He even appeared on Masha Yefrosynina’s show, “Dreams Come True,” an experience that convinced him he would one day return to Kyiv. In Poltava, his father insisted that he enroll in the local transport college to manage the family business later. Lado went along with it, even as the father’s business itself was crumbling year by year.

Lado never quite fit in at the college — his skinny jeans and Ugg boots set him apart, and the classes did not interest him either. Instead, he found work as an entertainer and event manager, which soon led him to meet Yuliya Rud, owner of Poltava’s Podium club. She was looking for someone who could shake things up with fresh formats and keep the young crowd coming back. Within a month, Lado became the club’s art director with a salary of $1,000, and completely abandoned college, so he was expelled in his third year.

Podium was more than just a club. It was a kind of micro-world: karaoke, a terrace, a beauty salon, a restaurant, and, symbolically, an actual runway. Fashion designer Andre Tan cut the ribbon at its opening, and its parties drew visitors from surrounding towns. Lado brought in new electronic music and popular DJs of the time, such as Ira Champion, Armo, Kemper, King Kong and Faraon. Young people posted photos on Instagram and tagged the club, turning Podium into a local sensation. Lado was not even twenty, Lado was staging events that reshaped the city’s nightlife. At one party, when trendy DJs from Kyiv played, 800 people packed the club — nearly triple the 300 expected.

In 2013, Lado took a gamble: he booked Monatik — who was then just starting his career — to perform at Podium. Covering the $12,500 fee and rider out of his pocket, the risk that club owner Yuliya Rud wasn’t prepared to take. And although he collected only $10,000, he did not regret his decision. “I lost $2,500 that night, but within a year Monatik’s fee had jumped to $30,000. That proved to me I could spot what was going to be a hit,” he recalls.

Alongside organising events, Lado began hosting them himself — parties, presentations, weddings. His style was light and modern, far from the old-fashioned contests and overused lines common at the time. By then, he was making about $2,000 a month.

2

In the wake of the Revolution of Dignity, the feeling of crisis hung in the air. The creative industry was undergoing a deep restructuring: big agencies were tightening their budgets, but new fashion and art clusters were emerging. It was then that Lado, already recognized event organizer in Poltava, got a call from Myroslava Bayun, owner of U21, a multi-brand boutique featuring Ukrainian designers. Her request was straightforward: “I need people in Poltava to start buying Ukrainian brands.” Lado’s suggestion was to organize Poltava Fashion Days. An event of this scale elevated Poltava’s status as a modern cultural hub that could set trends and draw a fresh audience — designers, journalists, bloggers, stylists. And, of course, customers.

Lado compiled a database of hundreds of Ukrainian brands and personally reached out to them. The cost of participation for a brand was a symbolic 2,500 UAH, just enough to cover the basics. “We promised them an audience, a new region. It was pocket change for Kyiv brands, but it opened a new market,” he recalls.

The debut season of Poltava Fashion Days brought together 20 brands. Lado used his personal connections. Among the guests were Vika Maremukha and Anya Sulima, contestants on the TV show Ukraine’s Next Top Model, who came to support the project. The event offered more than runway shows — there was also a market where visitors could buy items, and public interviews with designers. Although Poltava Fashion Days never turned a profit and lasted only three seasons, it later evolved into Verholy Fashion Weekend — resort-style shows at Poltava’s Relax Park. By then, however, major industry figures from Kyiv, like ARTEM KLIMCHUK, were coming to the show, and coverage of the events appeared in Vogue Ukraine.

During this period, Lado continued working at Podium while also travelling to Kyiv for fashion lectures, essentially living between the two cities. By 2015, Ukrainian brands he met at fashion events in the capital started approaching him for PR support. But he didn’t yet see himself as a fashion industry professional. Having moved to Kyiv and rented a tiny one-room flat in Podil with a friend, he completed the Professional Management program at Mercedes-Benz Fashion Days.

In Kyiv, Lado had no steady income. Occasional projects back in Poltava, and his old connections kept him going. He started job-hunting and going through his first interviews in the capital to understand what the market needed. With his last savings, he rented a separate tiny one-bedroom apartment and asked his friend Ruslan to design a website and help visualize his commercial offers.

In August 2016, at home, he launched Ladó Agency, his own PR agency. The monthly brand support cost was from €300 to €500. The agency promised full-service solutions: everything from photo shoots to placements in marketplaces like Vsi Svoi, plus visual concepts, PR, and creative management. Three brands he’d first connected with through Poltava Fashion Days immediately signed on, giving Lado his first steady income of more than $1,000.

One day, Lado got a call from Lidiya Smetana. Back then, her brand was known as Once LV. Today it’s One by One — one of the most powerful players in Ukraine’s mass market, with more than 25 stores across the country. Lado worked with the brand for five years. He enjoyed being close to new labels, watching how, with the right PR strategy and consistent support, an unknown name could rise to the top. At One by One, he managed it all, from rebranding — it was Lado who suggested the name now recognized nationwide — to collaborations famous across the whole country.

In 2017, Lado was invited to work as PR Director of Mercedes-Benz Kyiv Fashion Days, bringing his monthly take-home income to nearly $5,000. A year later, he took out a mortgage on a two-bedroom apartment — and paid it off in just two years. By 2021, his agency was managing projects for global giants like Givenchy, Guerlain, and Kérastase, primarily organizing events for new cosmetics launches.

Lado credits his success to a unique market offer his company had at that time. His agency stood out with creative newsletters, tailored events, and influencer collaborations made possible through the network of personal connections he had been building since his early days at Podium.

Before the Covid-19 pandemic, he rented an expensive office in central Kyiv, but he dreamed of working online to have more freedom and efficiency. When the pandemic gave him a legitimate reason to work from home, he felt relieved — Zoom meetings, a new format of planning, and cutting out unnecessary communication. During lockdown, the agency rebranded: a new website, logo, visuals, along with a broader range of services. By then, Lado had a team of seven working alongside him.

3

In early January 2022, Lado was preparing to move to the United States to study. He had enrolled in marketing and language courses at the University at Buffalo (SUNY), getting a student visa, and was about to pack his bags. Then came February 24 — the start of the full-scale war. Within days, Lado left for Ternopil to stay with friends, carrying with him $10,000 in savings.

Two weeks later, he legally crossed the border in his car, using his valid U.S. student visa, and headed to France. There, he joined communication work initiated by Ukraine’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, helping to organize fundraising events for Ukraine in Paris, Prague, Warsaw, Nice, and New York. The events featured MasterChef celebrities, pop stars Tina Karol and Monatik, and were hosted by television presenter Timur Miroshnychenko. In total, the initiative raised more than 20 million UAH (over half a million Canadian dollars) for United24 and the Ukrainian armed forces.

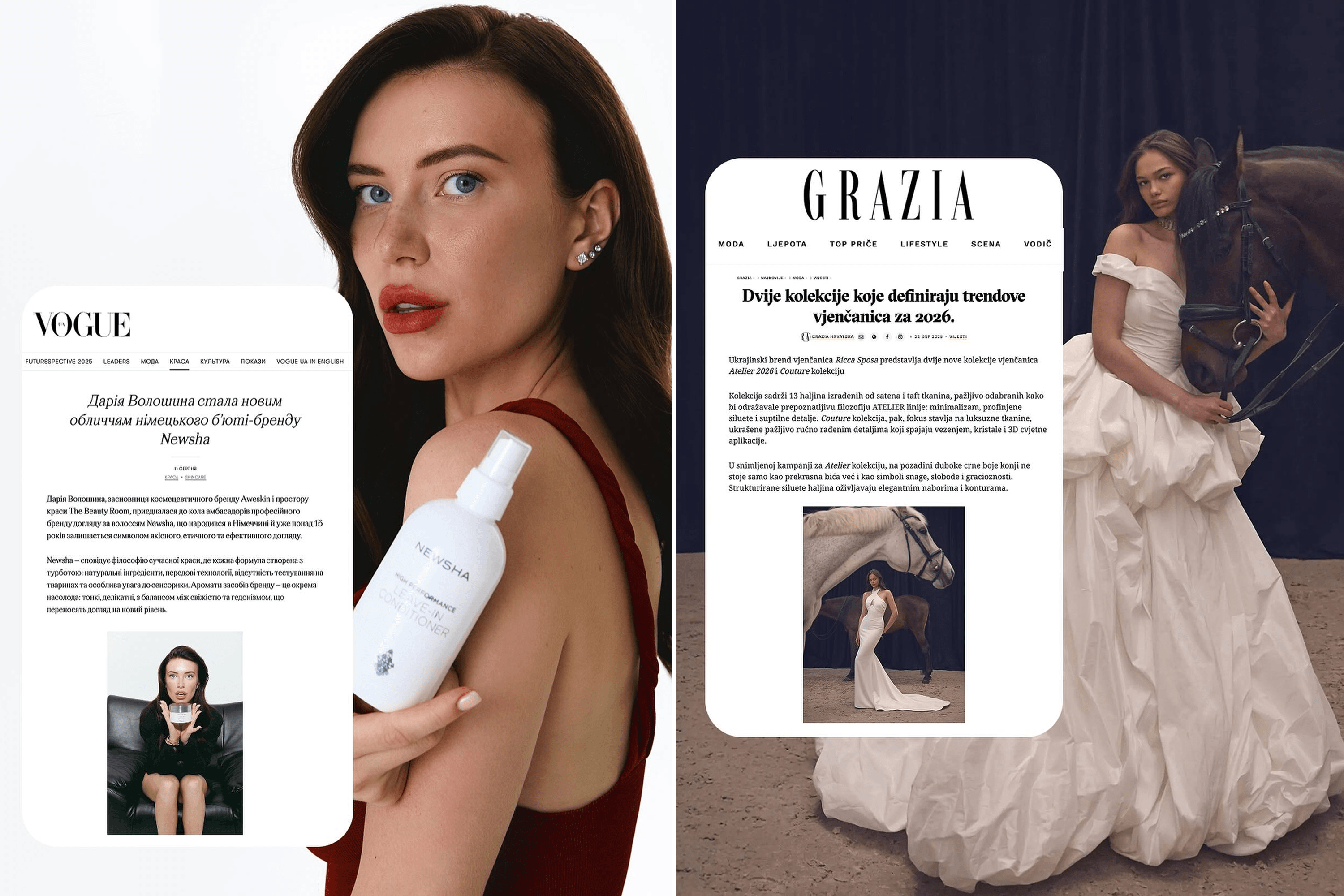

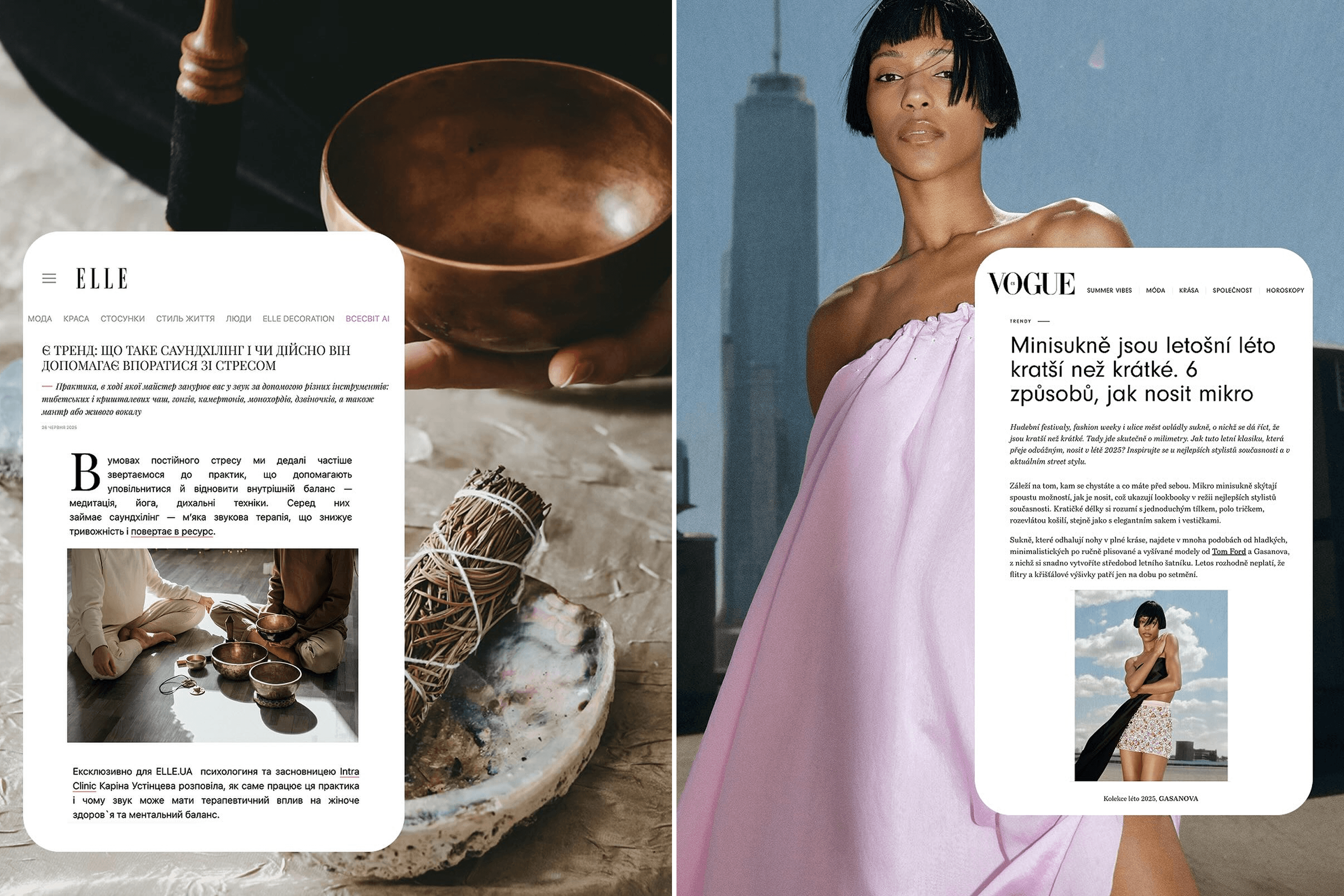

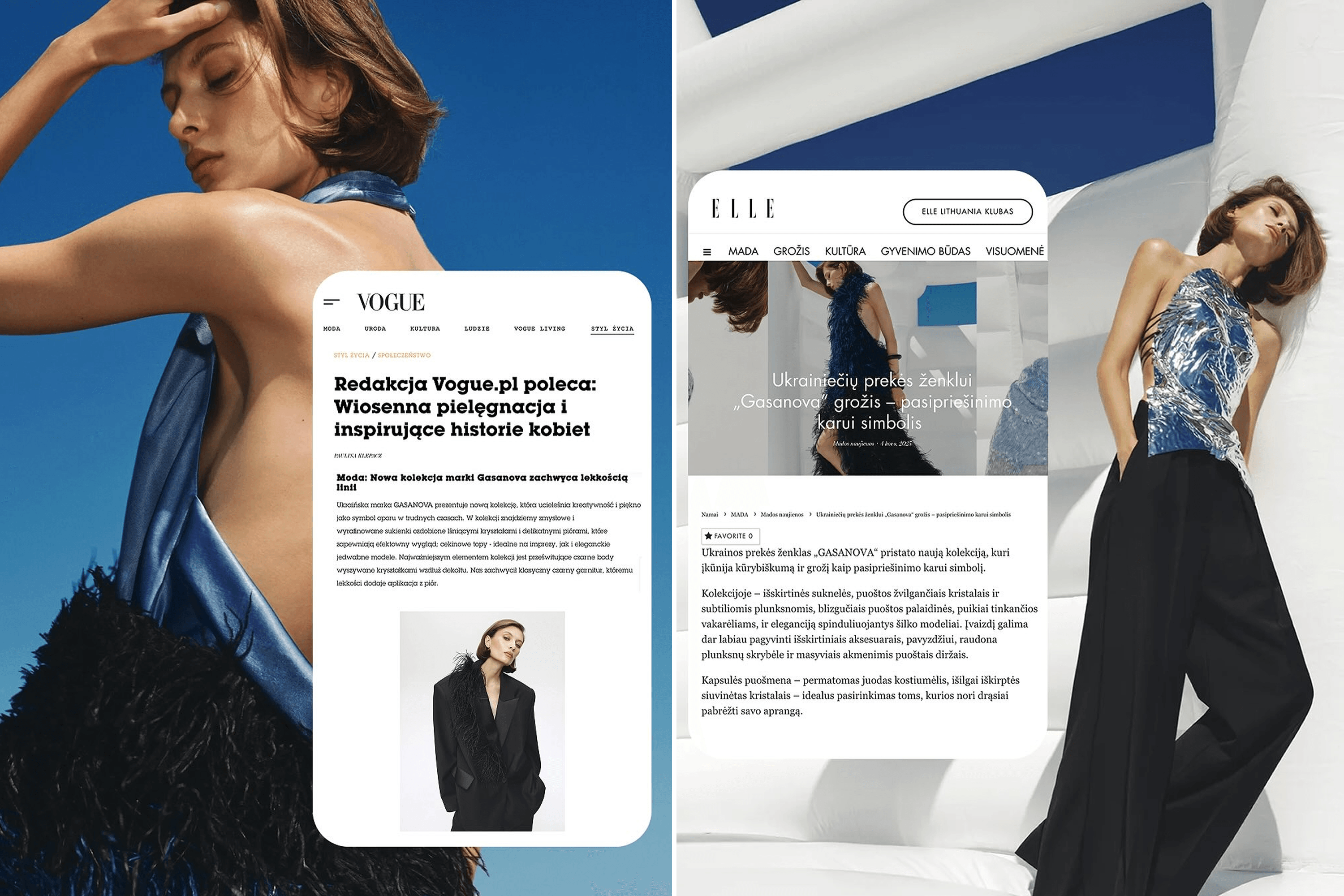

Within just two weeks, Lado’s PR agency was back in business. Some clients returned, while new ones came on board, thanks to its focus on European and North American markets. The company was mentioned in Western media, and influencers helped spread the word, many handling Ukrainian brands for the first time.

“Through the lens of our clients’ cases, we spoke to the world about the war in Ukraine,” Lado recalls. “One of the most impactful collaborations was with Alina Frendiy, who organized large-scale anti-war demonstrations in Milan and Paris. We highlighted this activity across social media and in the press — in particular, VOGUE Japan published a major article. At that time, the agency was working under exclusive conditions, at-cost basis, simply to keep paying salaries to the team,” he says.

In September 2024, Lado moved to New York under the U4U program, sponsored by his longtime friend Anna. He registered his own LLC, signed a long-term housing lease, and settled into life in the city. “In the U.S., I immediately felt at home,” he says. “Here, everyone is in the same position. This is a country of immigrants.”

To make himself known, he needed a high-profile project that could bring together interesting people and create a community. “I needed a reason to invite leading American influencers,” he recalls. That chance came when his client Rita Molchanova, founder of Grains de Verre, asked him to organize a pop-up. The project ran for 26 days in New York’s Soho district. It was there that the agency made its entry into the American market.

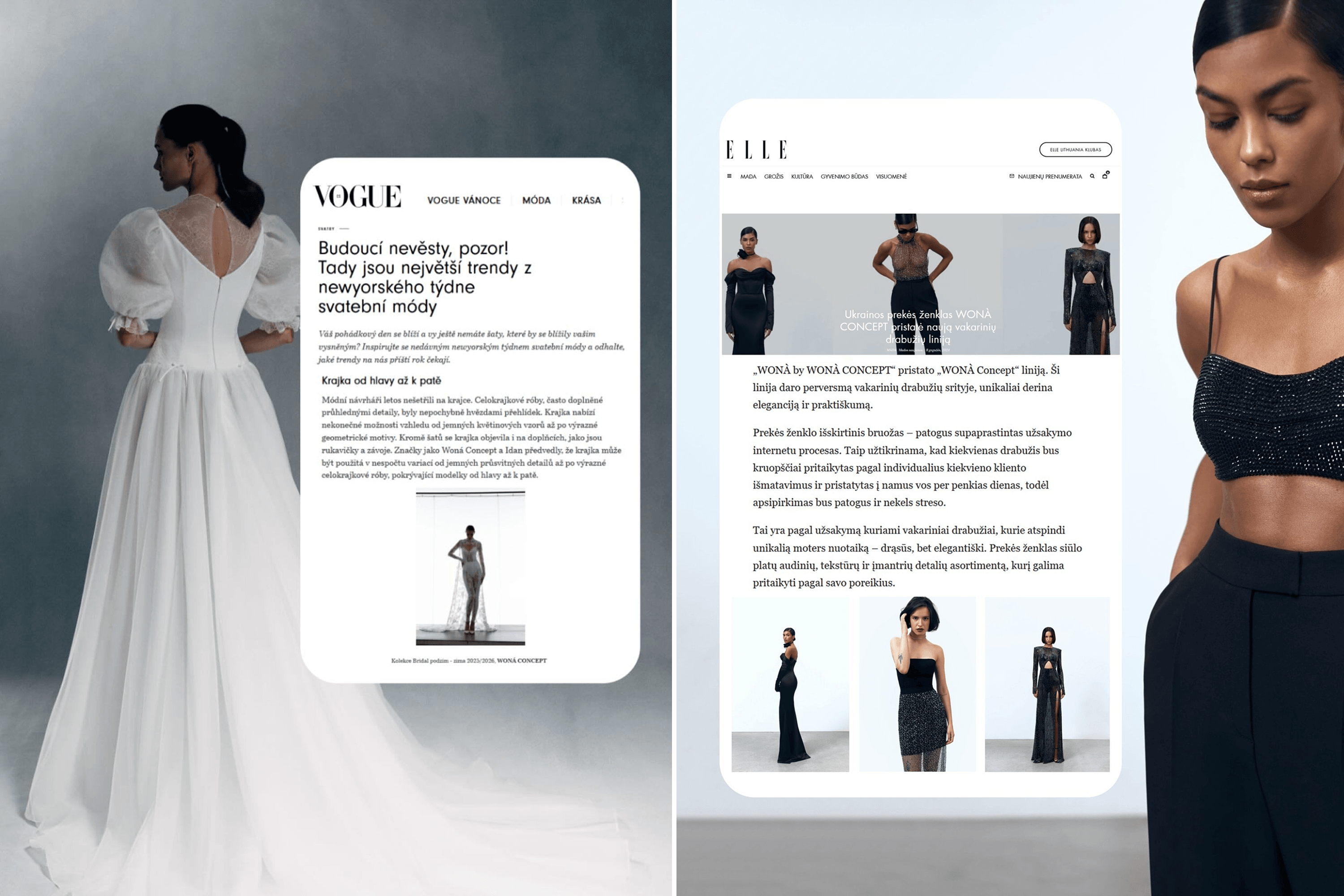

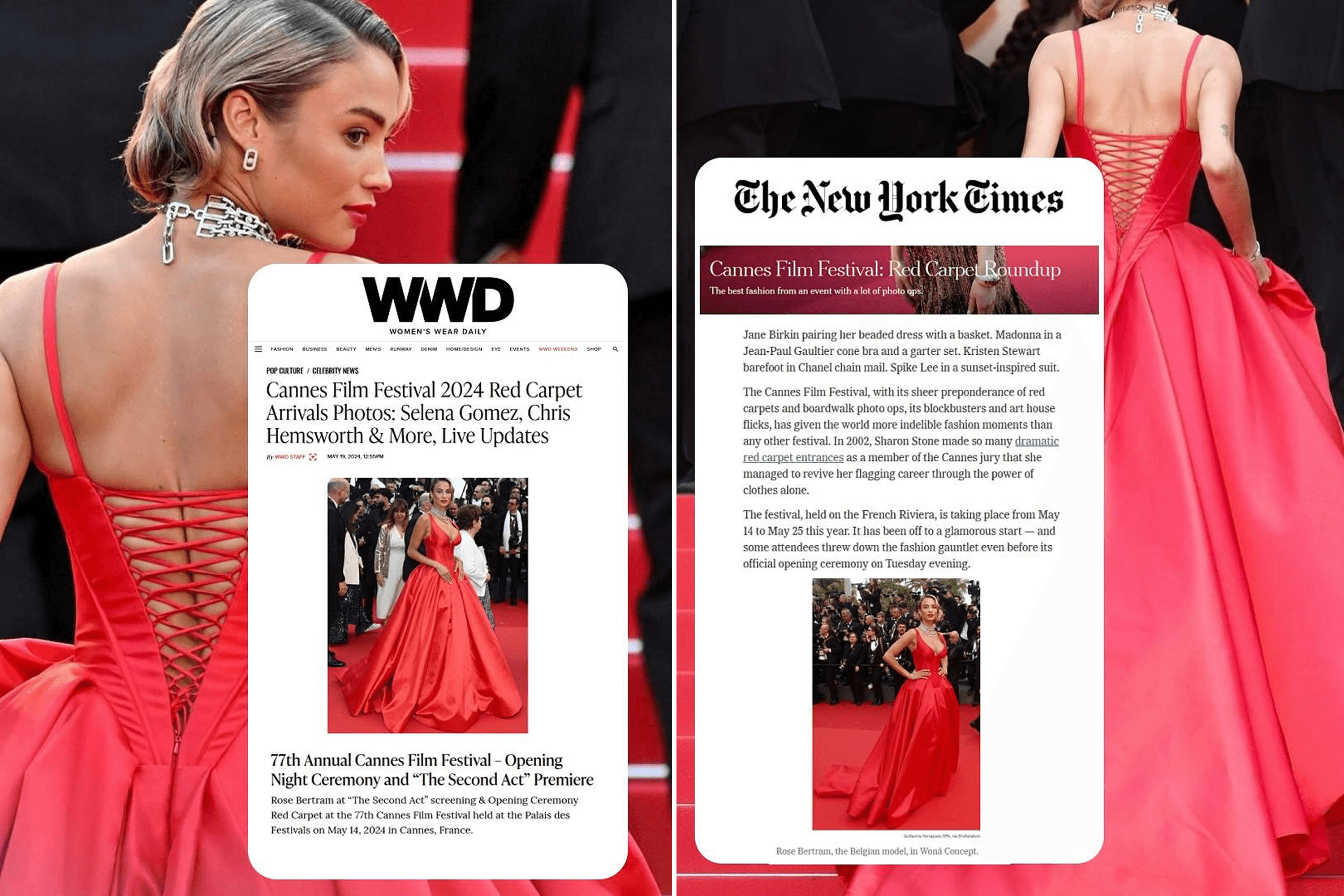

Today, Lado works with more than 20 clients from Ukraine and abroad. His portfolio includes brands like WONA Concept and Eva Lendel, both of which now have stores in New York and Los Angeles. In New York, he provides end-to-end support for Ukrainian labels — everything from strategy and PR to organizing pop-up events. Lado’s goal is not just to present Ukrainian products in the U.S., but to position them as serious players in the market.

Lado’s team also manages targeted pop-up projects for brands that are still testing the American market. Launching projects like this can cost up to $80,000, with only a few thousand profit for the agency. The rest goes into rent, production, logistics, and publicity, which Lado sees as the crucial factor: “To make a pop-up speak, you have to drive the conversation yourself. That means sending releases from media and Telegram channels, Facebook groups and WhatsApp communities to influencers in New York, Ukrainian stars in emigration, press kits — everything has to work in sync.”

Lado’s strongest network is the celebrity stylists, along with influencers and journalists from leading fashion and lifestyle publications. He constantly scans the market, tracking down contacts through LinkedIn, websites, email, personal assistants, and word-of-mouth referrals. Today, about 70% of his agency’s revenue comes from PR and brand support, with the other 30% from strategy, branding, and positioning. Most of his clients are Ukrainian, but their legal entities are already registered in the U.S., France, Poland, and the U.K.

“I sell chances, not illusions,” is how Lado formulates his business strategy. Every campaign is measured — traffic, reach, CAC, ROI. “Creativity matters, but it isn’t everything. Success doesn’t come to the most talented, but to those who know how to build a process — from data-driven analytics to multichannel reach.”

Today, his team includes 15 Ukrainian specialists working remotely — most of whom are based in Ukraine. The agency deliberately does not manage clients’ social media accounts, keeping its focus on strategy. Scaling up is not part of Lado’s plan: the agency will remain boutique, focused on trust and delivering results.

4

According to McKinsey research, customer acquisition costs in the U.S. fashion sector are among the highest in the world, ranging from $2,000 to $4,000 a month. The reason is fierce competition and information overload. Winning consumer attention means literally buying it — and it takes time and money,” Lado explains.

Lado believes that while Ukrainian craft and fashion are growing in quality, many brands struggle to break into the U.S. market. The key reason, he says, is the lack of tailored promotion strategies and in-depth market analysis. Tactics common in Ukraine — like gifting products to influencers and expecting sales from a single Instagram post — simply don’t work in the U.S. ROI in such campaigns is either minimal or non-existent.

Many Ukrainian brands often misjudge their business model. They try to operate in B2C, when their products actually fit more naturally into B2B. Young designers often point to the success of Ruslan Baginskiy, who built recognition through gifts to celebrities. However, what they overlook is that the brand’s sales were driven by buyers, the key players in fashion retail. “If you want to break into the U.S. market, you have to show up at B2B events and build direct relationships. It matters most for buyers that your brands are worn by celebrities — and only then does it matter for consumers,” says Lado.

Another strategic mistake of Ukrainian brands is the attempt to enter the market as a premium brand without the reputation to back it up. At its pop-ups in the U.S., Guzema Fine Jewelry competes in price with products from Tiffany or Bvlgari, but so far does not have the same level of recognition among American consumers. By contrast, Odesa’s Grains De Verre has taken a different path — positioning itself in the mid-range ($100–300), making it attractive for a first purchase from a new label.

Lado believes that brands also lack adaptation in their visual communication with consumers. Too often, their content looks like it was shot for a Kyiv shopping mall campaign: the same type of models — white, extremely thin, in typical poses. But the U.S. market is about diversity: different races, body types, and gender identities. A successful visual strategy requires localization built on authentic, relatable images that truly reflect its audience.

Another challenge is pop-ups in the U.S., especially in New York. Typically, they run from three weeks to a month. This is the optimal time for a brand to build awareness, securing a place in consumers’ minds and to build a steady flow of visitors. Shorter campaigns of 3–5 days only make sense for brands that already have an audience.

Planning a pop-up can take from a few weeks to several months. It’s a complex process — from finding the right location with large windows and a convenient entrance, to designing the space, handling logistics, and launching a promotional campaign. It is important to have a well-functioning sales system, a functional website, active social media channels, a team of brand managers and digital marketers, and above all, a clear marketing strategy.

The promotion of a pop-up relies on a few essentials: hosting special events, engaging local influencers and media, proactive press outreach, and well-placed targeted ads. Done right, it creates real lineups and helps the brand gain the necessary level of recognition among its target audience.

“A successful pop-up is not just about sales,” Lado explains. “It’s about creating a brand story that resonates with local consumers and lays the foundation for long-term growth in the U.S. market.”

While the U.S. market is open to international brands, it doesn’t hand out favours. Neither the “romance of war” nor a Made in Ukraine tag matters without a competitive product. The American consumer chooses goods based on quality and price.

“Ukrainian brands are genuinely strong — often much stronger than the average American retailer, many of whom have relied on outsourcing for years, without knowing what handwork or craftsmanship is,” Lado says. “Our craft is a competitive advantage. But without a system, it will remain just a beautiful hobby.”