YBBP journalist Roksana Rublevska and Masha Zhartovska met with Nomad’s CEO Mykola Kukharuk to find out how a small group of enthusiasts in Ukraine gave rise to a company that has became a symbol of flawless gem cutting.

In 1992, 20-year-old Mykola Kukharuk, originally from a village in the Kherson region, graduated from the Physics Faculty at Odesa I.I. Mechnykov National University. He was interested in mountaineering and rock climbing and went on to pursue a PhD to become a scientist. But the academic system couldn’t withstand the upheaval following the collapse of the USSR. When his scientific advisor he deeply respected — asked him to sell a coat at the market, Kukharuk realized, once and for all, that the state had no funds for science.

Like many at the time, Mykola turned to trading at the local market. He bought fruits and vegetables from Kherson state farms and sold them at a market in Odesa. Within a year, he had saved $5,000. Meanwhile, a university friend from their mountaineering club, Vladyslav Yavorskyy, had started selling crystals mined in Ukraine to buyers in Europe. Early exhibitions brought small deals, but Vladyslav saw potential in mineral fragments that held no value as collectibles. If cut properly, they could become valuable merchandise. Two of their mutual university friends joined Vladyslav — biologist Maksym Stepanov and geologist Sviatoslav Grygorenko. They moved to Kyiv and using descriptions from a book assembled their first cutting machines at the Arsenal factory. At that time, the factory accepted any orders just to avoid shutting down. In 1993, Vladyslav suggested to Mykola that they join forces to start a company, bringing the business plan, minerals, market insight, and connections, while Kukharuk contributed his trading experience — and together they entered the venture as partners.

That’s how the company Geoklyuch (Geokey) was born. They purchased Ukrainian topaz and beryl from the Volodarsk-Volynskyi mine — a site that, during Soviet times, supplied the military industry. Raw materials were bought for about $1 per gram, while cut stones sold for $2 to $6 per carat. Cutting increased the value of each stone by 5 to 10 times. That was the business model: buy cheap raw materials, invest skill and labour into cutting, and sell at a premium thanks to quality and unique shapes. The team cut stones right in the kitchens of rented apartments. Mykola also moved to the capital, which made business trips easier.

Kukharuk immediately began expanding Geoklyuch into the American market. He bought a car in the U.S. and, on a visitor visa, spent up to six months at a time travelling to trade shows from Dallas to Pittsburgh between 1994 and 1996. There were three types of exhibitions: one organized by local collector clubs, another — B2B exhibitions for local jewelers, and a third — weekend exhibitions aimed at retail sales of gems and jewelry.

The company’s weekly turnover then ranged between $5,000 and $7,000. The team spent money only on living expenses, reinvesting profits to purchase larger batches of stones. In 1998, Yavorskyy left the partnership to pursue work on his own. The remaining three — Kukharuk, Grygorenko, and Stepanov — launched a new company with the symbolic name Nomad’s.

By 2002, Ukraine’s reserves of topaz and beryl had been depleted. The team shifted their business model. Mykola began travelling to mines in Africa to source tourmaline and garnet, importing the stones to Kyiv for processing and selling them in Europe and the U.S. Rather than running their own mining operations, they bought directly from licensed local miners in Tanzania and Namibia. Local sellers were interested in making deals, so they handled export paperwork themselves.

In 2003, Mykola and Maksym relocated to Bangkok — the global capital of gemstone cutting. There, they opened a sales office and a workshop. Over time, they began to hire and train new craftsmen in cutting techniques. In 2011, Nomad’s opened a permanent office in New York City, on Manhattan’s 47th Street — the center of the U.S. jewelry industry — followed by an office in Milan in 2018. Since 2020, Nomad’s has also sold stones through a limited-access online store with access limited to professional jewelers, allowing them to keep pricing confidential.

Nomad’s presents itself as an international company with Ukrainian roots. The team has 20 people, four of whom are Ukrainian — and they were the ones who founded the brand: the three founders and Mykola’s daughter Maria, who now manages administration and marketing. Each year, the company donates a portion of its profits to the “Come Back Alive” fund and United24 to support humanitarian aid in Ukraine.

You dreamed of a career in physics, knew nothing about gemstones, were temporarily selling produce at the market, and then a friend started buying minerals, cutting, and selling them. What made you agree to join him and invest your entire savings?

I didn’t see myself selling vegetables at a market for the rest of my life. I had always felt a strong pull toward travel and adventure. Yavorskyy had a rare quality — he could inspire people with his ideas. When he suggested in 1998 that we each work on our own, I already couldn’t leave this business. I was completely captivated by it. By then, I had been successfully selling stones in the U.S. for four years.

When you founded the company, what was on your mind, and what was your vision?

It took us a few years to develop our own philosophy, which evolved and changed over time. At its core was the idea of building a company of friends, living an interesting life full of adventures and search for knowledge. In the traditionally closed world of the gemstone business, this approach was rather an exception.

Once we earned our first money and stopped worrying about our livelihood, the business became an adventure and a path of self-development. We sought not only results but also genuine relationships with different people. We also wanted to create the patterns of a stone’s facets that would reveal its beauty and bring out a genuine smile. For us, money was more an indicator of success than a goal.

Later on, our philosophy evolved to embrace a social aspect: we created a company where young enthusiasts, who have loved gemstones since childhood and have the proper education but cannot find a place in the industry, can realize their potential. Today, our team brings together people from different continents, and they enjoy working together.

We value beauty, friendship, and adventure. Now that I am over fifty, I think my next pursuit will be wisdom. When I find it, I’ll share it with you (smiles).

You said this business is secretive. Why did you take a different approach?

Because it felt closer and more enjoyable to us. I cared more about living an interesting and harmonious life than about which business strategy was “best.” We wanted a company built like a friends’ collective, not a rigid hierarchy.

We stood out not just in structure. We were almost the only representatives from post-Soviet countries. Our cutting style was so distinctive that professionals could immediately say, “This stone is theirs.” Our approach to presentation, communication, and even clothing — all of it made us stand out strongly against the rest.

Innovation is rare in the gemstone industry, so our originality at first sparked suspicion and absurd rumors”. Over time, people got to know us, became friends, and even adopted aspects of our style, including our cutting techniques.

Our openness helped too: we treated even competitors with friendliness. First, we thought, “Is there an opportunity for collaboration or partnership here?” rather than, “They’re competitors; don’t let them steal our secrets.”

How did you find your first stone suppliers in Africa in the early 2000s? There were no social networks or websites. Did you just fly in blind?

I first arrived in Tanzania in 1999, knowing only one thing: they had good-quality gemstones at affordable prices. I didn’t have a single contact or any kind of plan. I just walked the streets of Dar es Salaam, the capital, going into jewellery shops and asking about raw stones. One jeweller told me, “I buy my stones from those people,” and connected me with them. It turned out the main market wasn’t even in Dar es Salaam, but in another city — Arusha. I got on a bus and headed there. It was like a network: one person introduced us to another, and that person introduced us to someone else. None of the suppliers had websites. Everything was done in person. To find sellers, you had to speak directly with locals. For my first trips, I took $15,000–20,000, almost all of our working capital at the time. Payments were made in cash only.

How did you assess which sellers you could trust?

At first, it was purely intuition. But over time, rules formed. You learn who operates consistently, who has connections with exporters, and who has access to legal goods. Very quickly, you realize that reputation is everything in this industry. One lie, and a person is no longer recommended.

What stones did you buy back then, and how much?

Mostly rhodolites and tourmalines, priced from $20 to $30 per gram. There were also cheaper minerals that could only be sold with quality cutting — iolites, scapolites, and labradorites. With our level of craftsmanship, they became commercially attractive. One trip meant buying 100, 200, or at most 500 grams of raw material. It’s a small pouch. You buy the raw material by the gram, and when you cut a stone, you get about one and a half carats from one gram. Sometimes a little more, sometimes less.

That’s still a small volume. How did you manage to stay profitable? What kind of return could you get from, say, $15,000?

The entire model relied on the quality of cutting provided by Maksym and Sviatoslav. We weren’t aiming for volume. Our approach was to buy low-cost raw material, cut it with precision, and sell directly in the U.S. market. That allowed us to sell at five to ten times the purchase price. You’d buy a small pouch of rough stones, cut them, and end up with 40 to 50 finished gems, sold one by one. On average, turning $15,000 into $50,000-70,000 took at least six months of work — sourcing, cutting, and selling.

How did you achieve such high cutting quality?

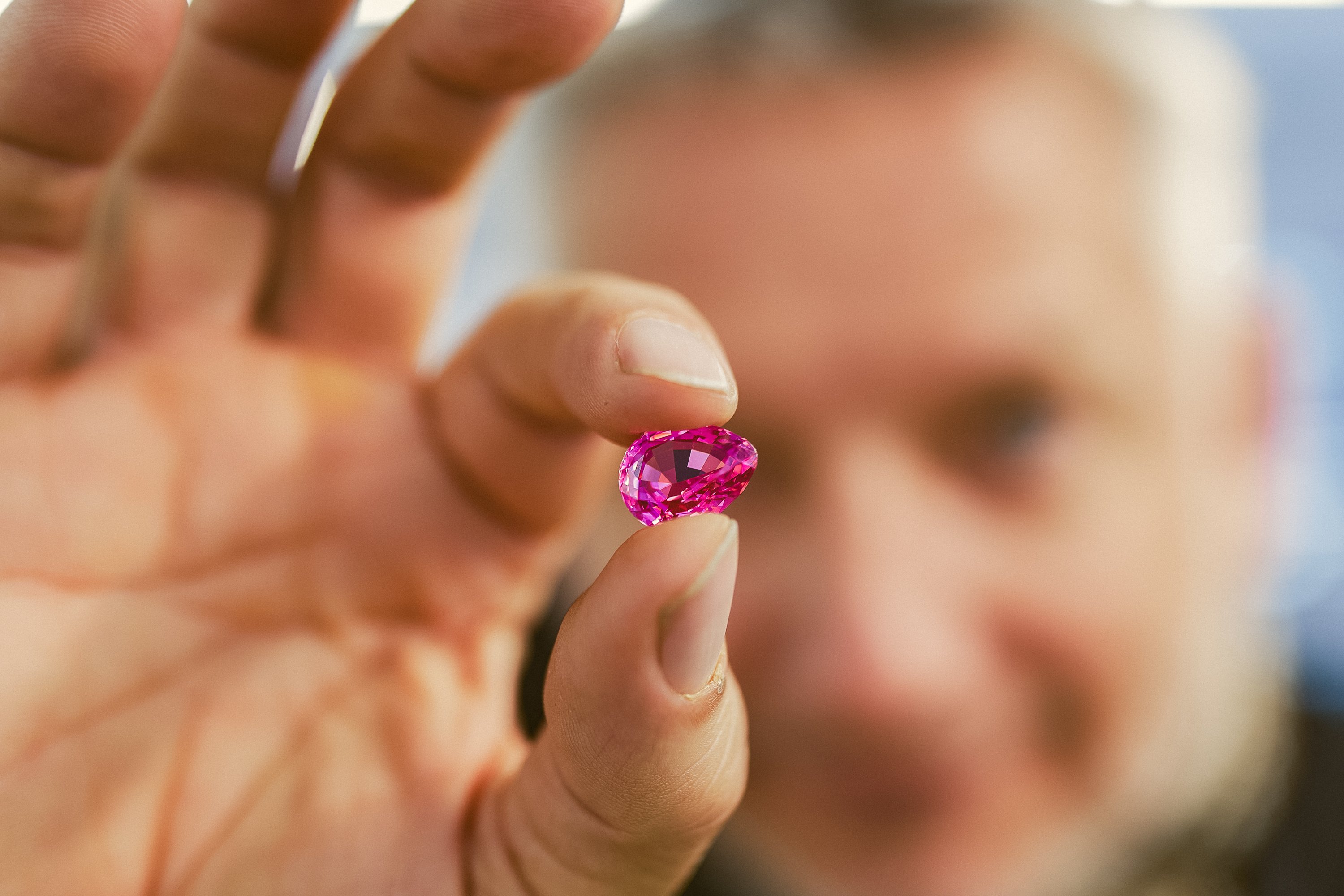

Creating a precise and unique cut takes more than manual skill. It’s a blend of science, experience, and a feel for the stone. You need to understand the mineral’s optical properties, especially its refractive angles, to enhance the way it reflects light and reveal its colour. Proportions must be pleasing, with every millimetre affecting the balance between beauty and weight. You also have to understand the raw material — recognize the type of inclusions, fractures, and stress zones to avoid losing weight or devaluing the stone. You work step by step: first comes the rough shaping, then the faceting, and only then — the delicate final polish.

You say you’re building a team across four continents. What principles guide your hiring?

Our first principle is enthusiasm. The daily lives of our buyers and sellers are nomadic: planes, cars, hotels, constant travel. Without enthusiasm, we would lose someone after a few years at that pace. A gem-cutter’s life is the complete opposite: day after day, in the same room, hours spent focusing on tiny details visible only under a magnifying glass. Without passion and love for their craft, a career like this is also short-lived.

Often, the people who join us are the “one in a million” — those who have loved minerals since childhood, became collectors, and dreamed of working with gems. After taking the first step graduating from a gemology school, such young people often find there’s no place for them in the closed and secretive industry. At Nomad’s, they get a chance to pursue their passion.

The second principle is harmony within the team. A new candidate must naturally fit in, be accepted by everyone as “one of us,” and share our philosophy.

The third principle is initiative and contribution. We’re a small company where everyone takes responsibility and finds their own niche. For example, our newest team member suggested developing our presence on social media, where we hadn’t been active at all before. She now manages Instagram, creates content, and interacts with clients who prefer to communicate through this channel.

We strive to cultivate a culture of friendliness, curiosity, self-improvement, and an aesthetic outlook. We aim to minimize hierarchical structures, listen to everyone, and give maximum freedom in decision-making within each person’s area of responsibility.

Does the company have an internal school or knowledge-sharing system for the craftsmen?

Some skills are passed from master to apprentice individually — almost like in medieval guilds. But most skills have to be built from scratch, with the support of colleagues. It’s similar to how a child learns to walk independently while relying on the help of those around them.

How did you handle logistics, especially moving stones from Africa to Ukraine and then to the U.S.? Were there any issues with customs?

Getting stones out of Africa wasn’t difficult. Each country had its own export procedures, and sellers handled the paperwork themselves. But importing them into Ukraine was much harder. Post-Soviet customs didn’t officially process gemstones, so we had to hide them in our pockets — it was deeply unpleasant. That’s one of the reasons we eventually moved production out of Ukraine. We’ve always aimed to run a transparent business.

Over time, our geography shifted. Raw materials were sourced from Africa, Asia, and Pakistan, while Bangkok served as the gemstone trading hub and a key market for buying and selling raw materials. In 2003, the two of us — Maksym and I — moved there and began hiring and training new craftsmen as demand grew.

How difficult was it to bring goods into the U.S.?

For many years, there was no import duty on gemstones in the U.S. You could declare them openly as goods for sale and pay nothing at customs.

If you made a purchase of $15,000 today, how much profit could you expect to make?

The money from the initial purchase comes back almost immediately, but the seventh or tenth stone tends to sell more slowly. Competitors took a peek at our designs and started copying them. There’s less raw material on the market now and more competition, so we currently operate with a markup of about 1.5 times the purchase price. What we buy for $15,000 sells for $22,500 — and a large portion of that margin goes toward company expenses.

Have you encountered ethical issues related to gemstone mining in your business? Or since you buy only from resellers, has that not been a concern?

We buy from resellers because purchasing directly from miners requires being at the mine at the time of extraction — which is time-consuming and complicated. The reseller collects and stocks the stones, so you either visit them or they send photos and offers. However, we have also been to the mines ourselves and have firsthand experience. For example, we have a partnership in Namibia where everything is official: the owner bought the land, holds a license, and pays taxes and export duties. We do not work with “grey” sellers.

Who are your clients?

They’re major jewelry giants whose pieces every woman dreams of. You probably know them all, but due to their confidentiality policies, we can’t mention their names.

Besides that, we work with independent designers and small jewelry businesses. Often, we don’t know the end customer — the stones are crafted into finished pieces by those closer to the client. These can be dealers, who take the stones from us on consignment.

I want to emphasize that we sell only natural stones, not synthetics. Jewelry brands working in the lower-priced segment of the market, due to high demand, offer pieces with synthetic stones. For the average buyer, the difference is hard to notice. Synthetic stones are prized for their perfect clarity, quality, and lower price compared to natural ones. They’re never tied to ethical mining issues and are widely available. But we operate in our own niche, legally, putting authenticity above all else.

How many regular clients do you have: independent designers and large brands?

We have about 12 large clients and roughly 50 medium-sized ones. There are many small clients, so many we don’t even keep track. Overall, our regular client base is around a few hundred.

You mentioned starting prices around $100 — but how much do the most valuable specimens cost?

Unique or very large orange garnets, sapphires, rubies, or emeralds. Our price range mostly spans from $100 to $200,000.

Does precious gemstone value always increase?

No. Sometimes you have to sell a stone for the purchase price — or even less. This happens when the initial appraisal was too optimistic, or when a stone sits on the market for years without attracting interest. What seemed unique and promising turns out to be hard to sell. The stone might be technically perfect, but it just doesn’t connect emotionally with buyers.

But do you somehow minimize the risks of these “slow-moving” stones?

With experience, intuition develops: you learn which stones have a good chance of selling quickly and which don’t. We learn from our own purchases.

Where do you find your clients?

Mostly, clients find us at trade shows. After the first deal, they recommend us to their contacts, and that’s how the network grows. For example, when we sold stones to a client in Taiwan, he helped us connect with other jewelers there.

Is that how you entered the closed markets of Taiwan and Japan?

So far, only Taiwan. We tried working with Japan and even traveled there, but couldn’t quite “shake hands” properly. The culture is very different, and doing business there isn’t easy. Each client requires a lot of time and effort. However, there are Japanese dealers and brand representatives who travel abroad to exhibitions, and deals with them are possible. Taiwanese clients, on the other hand, focus more on price-quality balance and are more open to collaboration.

Which trade shows do you participate in?

Tucson Gem and Mineral Show (once a year, in winter), JCK Las Vegas (once a year, in summer), Geneva Jewellery & Watch Fair (once a year, in spring), Inhorgenta Munich (once a year, in spring), and Hong Kong Jewellery & Gem Fair (three times a year).

I used to attend retail shows in the U.S., but now we focus on B2B, working with jewelers and industry professionals. Trade shows are a great opportunity to network. Often people ask, “Do you know anyone else who might be interested?” In major jewelry hubs like Paris, Geneva, and Northern Italy, there are brokers who help make introductions to clients or even take the stones themselves to sell to jewelers.

Our biggest breakthrough came in 2017 when we started actively managing our website and Instagram. That made us more visible online, and now people find us through Google, Instagram, and Facebook. It’s a completely different channel for attracting clients that complements traditional trade shows.

We also have a private online store accessible only to professional jewelers and business partners. This helps maintain confidentiality.

How do you stand out in the online space?

We currently have a team of 20 people, five of whom focus on photography, image editing, website management, and inventory tracking using specialized software. They also produce stylish presentations and Instagram videos, which play a big role in keeping clients engaged.

It’s not enough to simply find new clients. How do you keep them for the long term?

First and foremost, each of our stones is highly attractive, with a unique shape and play of light. Such a piece quickly finds a buyer at a jeweler’s and earns compliments, encouraging the jeweler to return.When a client comes looking for a new stone, it’s an important and difficult decision, as it involves a significant investment. That’s when they are met by our friendly team, who listen carefully, offer guidance, and assist without rushing. This builds trust, which can eventually grow into genuine friendship. About two-thirds of our sales come from repeat clients.

How do you verify the authenticity of the stones you purchase?

We don’t buy anything without proper verification. First, we take the stone for analysis, send it to a lab, and wait for the results — usually a few days, though it can take up to a month, which happens rarely. Only after receiving confirmation of authenticity do we proceed with payment. We need to check that it’s not synthetic. We evaluate the stone’s appeal and quality, including its color, clarity, and shape.

What about markets in less regulated regions, like Africa? Is it possible to operate there the same way?

The closer you get to the mine, the higher the risk of encountering synthetic stones. Reputation matters less there because the main goal is simply to sell. We’ve lost money a few times on synthetics but have learned to be cautious, especially with cut stones, since they’re harder to identify, so we rarely buy them. However, we know raw stones well — their shape and texture are almost impossible to imitate.

How is logistics between continents organized now? Do you ship cut stones?

Yes, only after cutting. We work with professional brokers and logistics companies who take care of customs and secure shipping — often, packages are delivered with armed escorts.

What does your company’s internal logistics look like?

It’s a complex system: our collection is spread across three offices. For example, a stone might be purchased in Milan but physically stored in Bangkok or New York. We centralize shipments through brokers, then deliver via FedEx or DHL. It’s crucial that all offices stay coordinated to avoid selling the same stone twice.

What is the company’s profit today, in 2025?

It’s hard to calculate profit precisely, but most of it gets reinvested into raw materials, production, marketing, and participation in trade shows. The company doesn’t have regular profit withdrawals. Each partner takes their share only when needed, usually for significant personal expenses.

Which stones are trending right now?

Blue tourmalines, red spinels, orange garnets, and aquamarines are currently popular.

How is the price of a stone determined?

The price depends on the classic “four Cs”: color, clarity, cut, and carat weight. But with colored stones, the most important factor is the hue. If it’s unique, vivid, and rare, the price goes up significantly. A stone without inclusions is valued much higher. However, even stones with inclusions can be valuable if the color is special — like Burmese rubies or tsavorite from Kenya, which are rare. And naturally, fashion influences demand for certain shades.

So, are trends in precious stones driven by brands?

Fashion is shaped organically by the people who wear jewelry. Mines and jewelry brands have only an indirect influence. I’m not sure anyone truly understands the details of how trends in gemstones are formed.

Are you planning to scale up to the mass market?

We won’t be working with brands like Pandora, for example. This is the quality segment of the mass market; such brands require perfectly calibrated, uniform, and inexpensive natural or synthetic stones. We’ve consciously chosen a different path. We want to keep two product lines: very expensive stones — unique, rare, investment-grade — and more affordable ones priced around $300 to $500 each. Even those affordable stones require a custom approach. It’s not a conveyor belt process. Each stone needs a handmade setting. Mass production is not our goal. We are growing horizontally but staying in the realm of one-of-a-kind pieces.

Do you ever keep any special stones for yourself?

Not yet. I tried to keep a few, but our salespeople convinced me to sell since there were interested clients. From a few specimens, I made gifts for my family — for my wife and daughters. I love stones, but more as stories and adventures rather than possessions. It’s enjoyment without ownership.

Is it important for you to be recognized specifically as a Ukrainian company?

We are not seeking recognition in Ukraine in time of war, we understand that people have other matters on their mind. Within the country, we aren’t thinking about it right now. Abroad, we used to present ourselves as cosmopolitans — global citizens with Ukrainian roots. Since the start of the full-scale war, however, we have consciously shifted our image and now emphasize that we are Ukrainian. We hope this at least somewhat helps remind foreigners about Ukraine and influences government and private support programs through democratic processes. For Ukrainians, it’s also a small but meaningful sign of support.