For 36-year-old Olga Tsybytovska, London has always played a special part. Born in Dnipro, she was drawn to British culture from a young age. In 2005, she moved to Kyiv, where she earned a degree in international analysis and English translation. To broaden her expertise, she headed to London and studied fashion business at Istituto Marangoni from 2009 to 2010. Later in her career, she worked for an agricultural holding in Kyiv, and in 2017, she returned to London for a summer course in art at Sotheby’s Art School. By 2019, Olga was back in Kyiv, building Foodmate, a culinary project that brought together tastings, dinners, and curated tours of craft producers. All the while, she continued travelling to London and actively following the city’s restaurant scene.

In February 2022, Olga came to London, this time on a romantic trip. But Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine changed her plans. Just two months later, together with her then partner, chef Yurii Kovryzhenko, and two colleagues, she opened Mriya Neo Bistro — a Ukrainian restaurant that quickly gained recognition in the British capital.

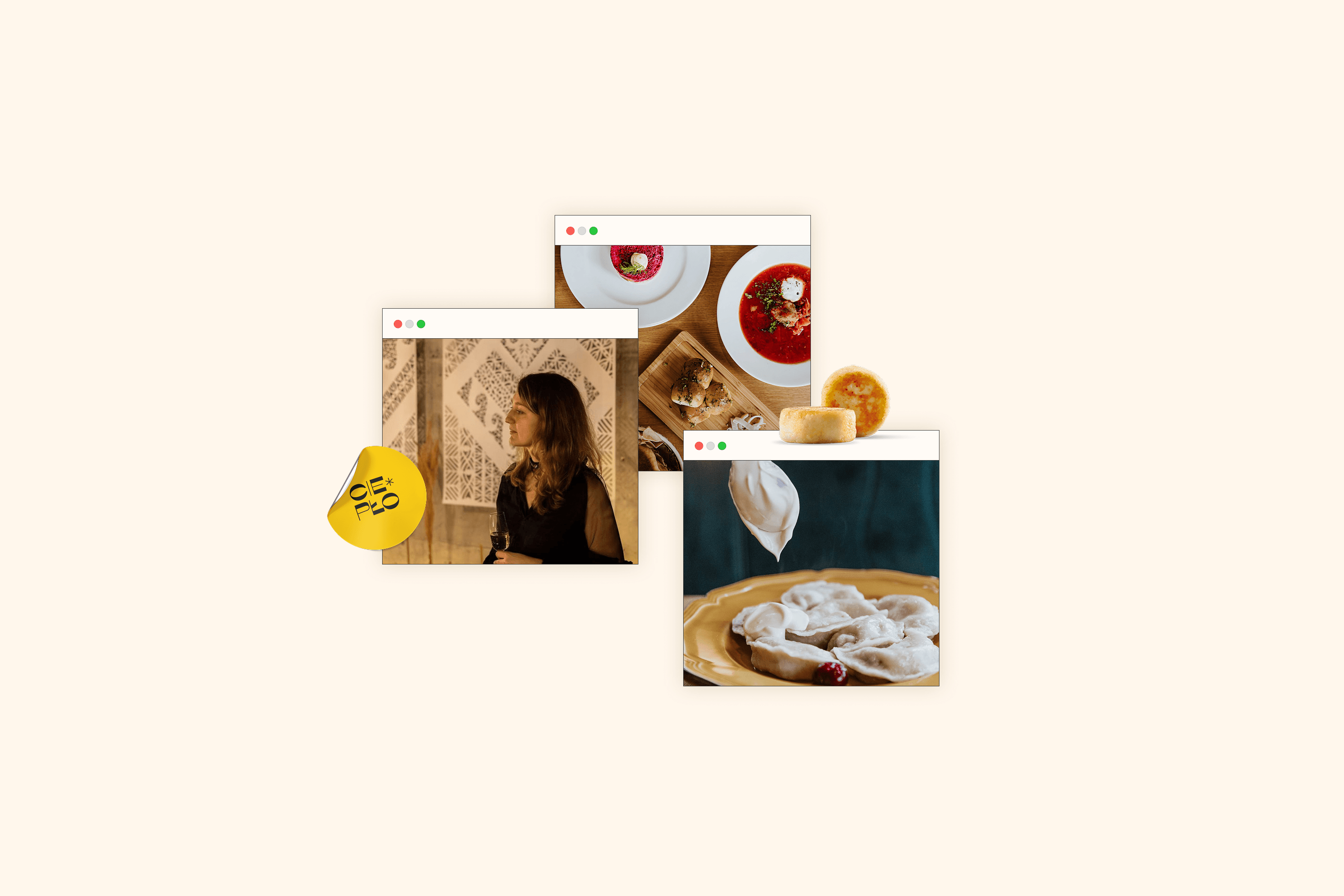

In this interview with YBBP, Olga talks about creating a restaurant in central London in just two months, the chef leaving three days after its opening, and how food has become her tool for cultural diplomacy.

Mriya Neo Bistro has been included in the following rankings:

- GQ Food and Drink Awards 2023 (Finalist in the “Best Breakthrough” category);

- National Restaurant Awards 2023 (Shortlisted in “Opening of the Year”);

- The Good Food Guide by CODE Hospitality (2023, 2024, 2025);

- CODE Hospitality’s Happiest Places to Work 2024;

- CODE Hospitality’s Women of the Year 2023: Campaigner of the Year.

You and your former partner, chef Yurii Kovryzhenko, were in London at the time of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. What followed?

At first, we volunteered at the Ukrainian centre. But it quickly became clear we could contribute in a much more impactful way. I knew London’s food scene well and had the right background, while Yurii was already an acclaimed Ukrainian chef.

The very next day, I approached a local restaurant with an idea for a fundraiser: a Ukrainian-themed menu, with all proceeds donated to World Central Kitchen. They immediately agreed. Soon after, Yurii was cooking at Jamie Oliver’s headquarters alongside chef and food writer Joe Woodhouse. This became possible thanks to our connection with food writer Olia Hercules, author Alissa Timoshkina, blogger Clerkenwell Boy, and their joint project Cook for Ukraine. That summer, we took things further by organizing a charity dinner featuring Yurii and four Michelin-starred chefs. The evening’s special guest was boxer Oleksandr Usyk, who generously contributed unique items for the auction: I had contacted his foundation and arranged his involvement through their director.

And that’s when the idea of your own restaurant came about?

After six months of charity work, we realized there was genuine interest in contemporary Ukrainian cuisine in London. Around that time, Yurii and I met our future partners — Bachi Gabunia, a Georgian who has lived and worked in the UK for over 20 years, and Ukrainian entrepreneur Olena Horbatiuk. They became our partners. Today, we are a team of three. About six months after the launch, Yurii decided to step away from the project.

Did each partner invest financially? How did you divide responsibilities?

Yurii was responsible for developing the menu, the kitchen, and the restaurant’s overall concept, but he didn’t contribute financially. I handled PR, communications, marketing and invested my own funds. Bachi invested funding and also handled the legal and administrative side: liaising with the local council, getting licences, opening bank accounts, and registering the company. For Ukrainians who had just arrived in the United Kingdom, going through all these stages on their own was nearly impossible. Having a partner with local experience and status was absolutely essential. Olena Horbatiuk also invested money.

A restaurant is a long-term project that lasts for years. What gave you the confidence to trust your partners so much at the very beginning?

That’s a very good question. We met Bachi Gabunia only a few months before setting up the company. As for our Ukrainian partner, Olena Horbatiuk — who remained in Ukraine after the full-scale invasion — we didn’t meet her in person until the restaurant had already been operating for five months. Before then, we only knew her online.

Yet, at the start, we were all so inspired by the idea and believed in the common cause that we didn’t even allow ourselves to think about risks. I relied completely on Yurii: he had been in the restaurant business since his youth, had prior experience opening restaurants abroad, and I was confident in his expertise. Bachi understood the UK business system inside out, had valuable connections, and a stronger command of legal English. Olena, meanwhile, was meant to be a “silent investor,” without involvement in day-to-day operations. At that stage, we believed we each understood our roles in the venture.

Can you share more on how and when Yurii left?

It never even crossed my mind that we might face conflicts. Yurii was the face of the restaurant, the creative force behind its menu and concepts. He hadn’t invested financially, but his expertise was invaluable. At the time, we often said: anyone could leave, but never him. Yet, just three days after opening, he left on assignment — supporting the Ministry of Foreign Affairs with events promoting Ukraine in Asia. The kitchen was suddenly without its head chef, and that was a huge challenge. The third dinner was already happening without him. When Yurii returned, it was time to refresh the menu, but by then he was sharing his time between Mriya and a project in Latvia. He was working on two fronts while our restaurant was still only a few months old.

Looking back, I know for certain: a chef must be present daily, especially when the team is still inexperienced. His absence dealt a serious blow to all processes. At that time, the kitchen was held together by Natalia, our sous-chef, who kept the kitchen afloat during that time, and I am deeply grateful to her. I sincerely relied on Yurii — as a partner and as an artist. In the Western world, the chef is the heart of the restaurant. And when a much-PRed opening in London loses its chef, it’s quite close to a disaster. I insisted that we redefine his role as a brand chef — an executive chef who would return periodically to update the menu and host special events.

Did his departure from the business and from your relationship happen at the same time?

Yes, they happened simultaneously. But the end of our relationship wasn’t the reason he left the business. Our relationship began to fall apart after his departure on the third day after the restaurant’s opening. Amid emotional exhaustion, it felt like a betrayal.

Did he disengage right away?

For the first six months, he would come, work for a while, and then leave again. But in February 2023, he formally stepped away from the project. We found out through a WhatsApp message: “Thank you all, it’s time for me to go.”

Did you have any legal agreements in place regarding his responsibilities?

None at all.

Do you believe he would not have left if there had been formal legal obligations?

If he had invested his own money or had clearly defined obligations for several years, he would not have left so easily. But with Yurii, everything was based on trust. There were no formal contracts — only a verbal understanding and a shared belief in the idea. By then, he had already started another restaurant project in another country.

What would you do differently now?

First of all, before putting in any money, it is crucial to hire a lawyer. Roles, duties, and responsibilities must be set out in writing, regardless of the kind of relationship you may have.

How did you cope after his departure? Who took charge of the kitchen?

We tried to maintain quality through internal resources: the sous-chef, Bachi’s vision, and my own. Formally, we kept Yurii’s menu. But when spring came and seasonal ingredients appeared, we had no choice but to update it — a winter menu simply couldn’t stay.

Who developed new dishes after him?

In the fall of 2023, Oleksii Krakovskyi came from Ukraine for a month to design a new menu, train the kitchen staff, and lead special events. The role of head chef went to Tetiana, who had originally joined us as a pastry chef. She is the only member of the team who has been with us from day one and is still here today.

In September 2024, executive chef Anton Vasyliev joined the team. Based in London, he is a regular presence at the restaurant and now leads the creative component and seasonal menu updates.

Why did you choose the name Mriya for the restaurant?

Honestly, there were no other options. Mriya was the first and only name that came to me. And interestingly enough, it was also the first idea Yurii had. We met, exchanged ideas, and it turned out that both of us had thought of the same thing. The name “Mriya” is very symbolic. At the entrance, it says: “Mriya means dream.” It also refers to the legendary Ukrainian aircraft Mriya, which became a symbol of strength, hope, and talent. And beyond that, it is also my personal dream to make Ukrainian cuisine recognizable in the world. I am convinced we have every opportunity to achieve this.

You opened in August 2022. How much time did you have for renovations, furniture procurement and developing the concept?

We moved into a 120-square-metre space in mid-June 2022. By August 10, we held the first dinner — the so-called Soft Launch. The official opening and the start of reservations took place on 31 August. Within those two months, we managed to renovate the space, hire and train a team. Yurii developed a menu of 24 dishes. We launched a communications campaign — almost all local publications covered our story. There was also international attention: CNN from the United States, as well as television from China and Germany.

Did you move into a ready-to-use space, or did you have to build everything from scratch?

The premises already had furniture and equipment — there had also been a restaurant there before. However, we needed to renew licences and certificates, set up and implement food and safety procedures, have the team go through certifications, find suppliers, sign contracts for product deliveries, and connect essential services (internet, phone, booking system, laundry). We signed a lease agreement — the building is fully owned by our landlord, who had previously managed a restaurant there himself. The restaurant is located on the ground floor and in the basement, with apartments above it that are rented out and occupied by tenants. It’s located in Chelsea–Kensington, near Earl’s Court in West London’s Zone 1, close to the Victoria and Albert Museum. The restaurant seats 70 guests.

Who designed the space, and how did you choose Ukrainian makers for the interior?

The renovation and overall design of the space were done by the Lviv-based studio RePlus. They also produced and assembled the furniture and sourced the facade tiles from the company Leoti. Our textiles are from the brand Gushka, and ceramics from Guculia. The wall art — by contemporary Ukrainian artists, including Leonid Bahrii, Alla Alekseieva, Arkhip Nizhenskyi, and Vasyl Yolokhov. We also had a piece by Anastasiia Bilous, who helped us with communication with the artists.

One particularly meaningful detail is “Kvitucha” (Blooming), an art piece by Andrii Matviichuk created on the front line. For the kitchen, we ordered aprons and jackets from Abrikos, while the T-shirts came from Khomusko Design Studio. And for borshch, we had plates made specially by Maistrenko Ceramics.

What makes the restaurant Mriya unique among other Ukrainian restaurants in London?

When we opened, there wasn’t a single Ukrainian restaurant in central London. The others were further out, with a more traditional approach.

Our concept is a neo-bistro showcasing contemporary Ukrainian cuisine without old-fashioned attributes. We bring tradition and modernity together in the interior, the menu, and communication: antique furniture and tiles from Lviv alongside modern Ukrainian design. And in the menu, where classics like borshch are placed alongside new ones — for example, our tomato and stracciatella salad, dressed with roasted sunflower oil for a distinctly Ukrainian accent. For us, the kitchen is a living organism that evolves.

Please tell us about your collaboration with Rick Stein. Did it have an impact on the restaurant’s popularity?

Rick Stein — a well-known British chef and host of the BBC program Food Stories — visited us in the summer of 2023, as he was planning to film an episode on borshch. It was a meaningful moment for us, because his audience is primarily British. When the episode aired in February 2024, we noticed a significant increase in visitors who came after seeing us on the BBC. This helped not only to popularize our cuisine, but also to present Ukraine through culture and food, and not only through the war. The experience confirmed for us that Ukrainian cuisine has a rightful place in multicultural London.

How do foreign guests usually react to Ukrainian dishes?

Overall, they respond well to Ukrainian cuisine. In all my experience, I haven’t seen guests reject a dish due to misunderstanding or dislike. The only exception was a period when we served red mullet — a small fried fish with many bones, which frightened some guests. This is the only significant cultural difference I noticed. This is the only significant cultural difference I noticed. Borshch can sometimes feel unusual to them when the vegetables are served separately from the broth, but they still enjoy it. Fatty pork doesn’t surprise them either, since the British also enjoy it.

In the early days, many guests came because they wanted to support Ukraine and experience our culture through food. Now, many people are tired of the war. Do you notice this?

At first, many guests came because they wanted to support Ukraine. But over time, the audience has broadened. Today, many of our guests are simply curious about our cuisine and culture. The restaurant has grown from being a place of solidarity into a popular dining destination in London. And that’s important to us — we don’t want people to come out of pity. The social and cultural elements remain, but visitors now see us like any other restaurant.

From the very beginning, we focused on introducing people to Ukrainian food. When Ukrainians tell us that the flavours remind them of their mother’s cooking, it gives us wings. And when British or international guests say they’d never encountered Ukrainian cuisine before, but tried it here and plan to return — that’s equally inspiring. We are open to all guests, not only Ukrainians. Overall, Ukrainians make up about half of all our visitors.

Has the restaurant reached financial self-sufficiency? If not, when is it expected?

We have not yet reached full self-sufficiency, we need about three more years. In the UK, restaurant industry profitability is generally no higher than 15%. If you’re achieving 12%, you’re already doing very well. We’re only now moving closer to that benchmark.

Do you collaborate with other Ukrainian businesses in London?

Since the beginning of 2024, we have been working with the supplier Ukrainian Wines in UK, a supplier of Ukrainian wines. Together, we’ve hosted wine evenings featuring winemakers such as Beykush and Kolonist, as well as themed tastings with Koblevo (Bayadera Group). For three years running, we’ve also organized Christmas and Easter markets with boutiques like I am Volya, Izum Antique Store, and floral designer Mariia Yaremchuk.

What is your team like? Are all of your staff displaced from Ukraine?

We opened with the idea that the restaurant was created by displaced Ukrainians and staffed by people who had come from Ukraine. This concept remains relevant to this day. Our entire team, apart from one colleague from Honduras, consists of Ukrainians who arrived in London after the full-scale invasion. From the beginning, media coverage of our opening emphasized that we are a Ukrainian restaurant. Beyond the culinary side, there’s also a social component, as we operate in a very difficult time for Ukraine.