Olena Borysova is a restaurateur, economist, and CEO of GastroFamily, one of Ukraine’s largest restaurant groups. Today, the company runs more than 60 establishments across Ukraine, Poland, Slovakia, and Portugal, from Ukrainian cuisine restaurants to steakhouses and bars. For 15 years, Borysova built the business together with her former husband, Dmytro. He was the public face of the brand, while Olena was responsible for operations.

When Dmytro left the company in December 2024, Borysova took full control over it. She now leads a team of more than 1,500 people, managing company-owned restaurants, franchises, a food delivery service, and projects that help veterans transit back to civilian life. She is also raising five children, a role she openly calls her most important work. In 2026, Borysova plans to introduce two new restaurant concepts, launch a strategic consulting agency, and publish a book for women based on her journey and experience.

Yellow Blue Business Platform journalist Sofiia Korotunenko spoke with Olena Borysova about operations in Ukraine and abroad, the group’s new projects, the realities of wartime, and how she balances it all.

1

I’d like to start by asking about the first days of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. How did you experience the beginning of the war?

I’m a romantic by nature, so I didn’t believe a full-scale invasion could actually happen. At first, we sheltered with our neighbors, but the explosions and helicopter noise kept the children crying constantly. Eventually, we decided to evacuate. The traffic was terrible, fuel was impossible to find, but we managed to reach family in the Carpathians.

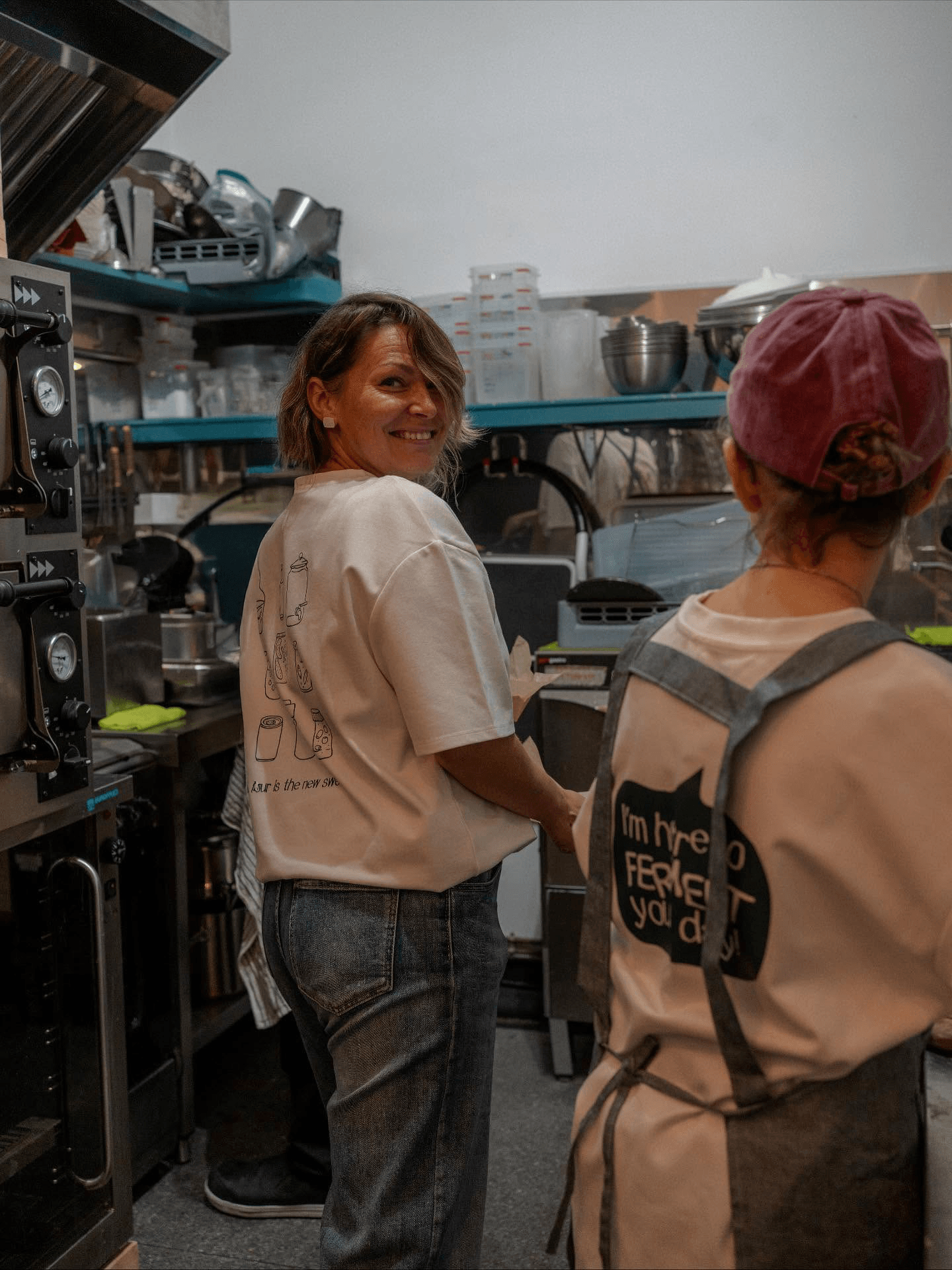

I kept in constant touch with my team. Some were evacuating, others stayed in Kyiv. My priority was making sure everyone was safe. Obviously, we didn’t open on February 24, but within days we’d turned our kitchens into volunteer operations, feeding soldiers and civilians, anyone who needed a meal.

My team was incredible. They got the kitchens running, pulled together chefs from all our locations, found organizations that could supply food, and brought hot meals directly to the front lines. They even made Molotov cocktails as no one knew how far the Russians would push. They risked their lives. The team worked everything out very well. By May, like other businesses, we’d reopened most of our restaurants.

You had establishments across Ukraine. Which were damaged in the war?

We lost our place in Mariupol. The ones in Kharkiv and Irpin were destroyed by Russian shelling, too damaged to rebuild. In Kyiv, our franchised Philadelphia at Lavina Mall was hit. We’ve had to rebuild our Barsuk gastrobar in the Lukianivka neighborhood six times after repeated strikes. Still, guests keep coming. They understand the situation and no one says, “The windows are broken, so I’m not going there.”

Aside from the constant shelling, what are your main challenges now?

Getting people to come out is extremely difficult. With continuous attacks and blackouts, going out to eat isn’t a priority. Dining habits have shifted too, even how Ukrainians choose where to go. Central streets like Khreshchatyk in Kyiv are empty, even on weekends. Instead of traveling across the city, people stick to places in their own neighborhoods, in residential areas.

We can see that diners are ordering less. The average check used to include three dishes, now it’s two. A glass of wine or dessert isn’t in the budget anymore. People are spending less, but still come for coffee and their favorite dish. I think it’s their way of holding onto some sense of normal life.

You mentioned that fewer people are going to restaurants in the city center. That’s where your higher-end venues are: Ostannya Barykada, Kanapa, and the Hutsul steakhouse Vatra. How has attendance changed, and how hard is it to keep these places running?

Kanapa lost its main audience of foreign tourists. The regulars at our Asian steakhouse Oxota na Ovets, in the Vozdvyzhenka neighborhood, mostly left in 2022. Traffic at classic format places has also dropped as people have less money to spend. They simply can’t afford to dine out as often as before.

Two of our restaurants are heavily seasonal. Vatra does well in summer thanks to its covered terrace with a fountain, but it’s harder in colder months. For Ostannya Barykada it’s the opposite. Without a summer terrace, it sees less traffic in warm weather but runs effectively from November through March. Of course, “effectively” means something different in wartime. Before the full-scale invasion, Barykada would see over 2,000 guests a day, many of them tourists. Now it’s 300–500, mostly locals, soldiers, and the occasional Kyiv visitors.

Our other locations have seen drops too, but not as sharp. We’re getting by thanks to staggered seasons across our restaurants, an anti-crisis plan we built with the team, and most importantly, thanks to Ukrainians. Young people especially want to buy local and support each other. It’s tough, but we’re not done yet.

How are your QSR spots doing during the war, places like BPSH and the Bilyi Nalyv cider bar?

Our QSR formats run on volume, and in that sense they’re actually growing. People are choosing more affordable spots than they used to.

At Bilyi Nalyv, for 200 hryvnias you get a glass of cider, a Fine de Claire oyster with lemon, a hot dog, and you can dance to a DJ set and relax with friends. People spend less per visit, but we’re seeing more of them.

Do you feel like you’re adapting to the full-scale war?

I’ve been in the restaurant business for 24 years, but I’ve never faced anything like this. My team and I aren’t just solving problems. We’re transforming how we operate and looking for new directions. Any crisis can push you to finally act on ideas you’ve been sitting on, or come up with new ones.

When COVID hit, we launched our own delivery service across all our restaurants. Now we’re developing formats that can work during and after the war, in small towns and big cities alike.

We’re adapting to what’s in front of us, but also planning ahead for the postwar period. I study history. I want to understand how HoReCa evolved after World War II, what people ate, what ingredients were available. Based on history, we’re looking at about ten really interesting and hard years ahead.

We haven’t rolled it out fully yet. It’s a franchise model designed specifically for veterans. The state offers grants and low-interest loans for these franchises, but there’s one big problem. The funding only covers alcohol-free establishments. All our current places serve alcohol. So for the past two years, we’ve been creating a format that fits those requirements, and we’re almost ready.

First, we’ll open one ourselves as a pilot, hopefully in 2026. Then we’ll scale it for veterans. I’m absolutely certain this is going to be huge. We already have veteran franchisees. Two soldiers who became friends during the war opened Bilyi Nalyv locations in Lutsk and Rivne on their own.

We also have another program for veterans. We help them transition into restaurant work, as chefs for example. Our professional cooks teach them, and military psychologists provide support. We launched this at Ostannya Barykada because the space is fully accessible. Braille menus, adaptive plates for people with prosthetics, wheelchair access, everything.

My friend, Ukrainian TV host Uliana Pcholkina, who has been using a wheelchair for many years, tested the space for accessibility. We thought through every detail. Not all our locations are there yet, but Barykada sets the standard in Kyiv.

Can you tell us more about the new franchise format for veterans?

It’s a smaller concept requiring up to $50,000 in investment. We’ll offer two versions. One with alcohol for regular entrepreneurs, and an alcohol-free version so veterans can access state grants and special financing.

Back to the war’s challenges. How hard has the staffing crisis hit you? How did the mass departure of women in 2022 and the new rules letting men aged 18–22 leave as of August 2025 affect you?

We employ around 2,000 people. Yes, we’re short-staffed, and the war has affected us. But honestly, I don’t even know how many people left, because it hasn’t impacted our operations. Our processes stayed smooth, and we’ve never had to close a location due to staffing. Shelling, blackouts, generator failures — that’s what really hits us.

Two thousand employees is a lot. How do you manage so many people effectively?

GastroFamily used to have 84 senior managers running different concepts and individual locations across Kyiv and the regions. In summer 2025, my team and I changed our strategy. I gave managers and restaurant leads more autonomy, because right now, decisions need to be made quickly.

I also cut those who didn’t believe in what we were doing or our strategy. Without belief, nothing works. I brought in fresh talent, but my core leadership has been with me for years. Eighty percent of them. And about 60% came from places like McDonald’s and KFC, so they understand operations. Our operating mode right now is “fasten your seatbelts, we’re taking off”.

2

In 2022, GastroFamily went international. We now have six Bilyi Nalyv cider bars across Poland and Slovakia, plus Mushlya, a seafood spot in Portugal. How hard was it to expand abroad, and had you planned this beforehand?

I’d already worked internationally. Back in 2017, we opened Kanapa in Warsaw but sold it when COVID hit. About ten years ago, we also had Crab’s Burger, a seafood place, in Spain and Kazakhstan. Both closed for various reasons.

When my former husband Dmytro and I created Bilyi Nalyv in 2018, we set out to make it Ukraine’s top cider bar. We did. Next came European expansion. The war accelerated everything. In April 2023, we opened Bialy Nalew in Wrocław. It’s already paid for itself and is doing very well. We’ve sold over 15 franchises total, though only six have opened so far. Five in Poland, one in Bratislava.

A lot of Ukrainians moved abroad, saw this war would drag on, and decided to build something. Those are the people behind our franchises. For them, it’s perfect. The brand is known, the model works, and it scales internationally. The setup is straightforward: small staff, tight menu, quick service. Way easier to run than a full-service restaurant.

Are all your franchisees Ukrainian, or do locals own any?

Every single one is Ukrainian. They’ve run restaurants or other businesses before. It’s critical that owners stay hands-on with daily operations. Only later can they hire a manager, once they understand the operation inside out.

Our European partners share responsibilities with their hired managers. That level of owner involvement is what makes the model work.

You mentioned Kanapa in Warsaw. Why did you have to close it? What would you do differently today?

Everything was going well until COVID hit. Restaurants across Warsaw shut down, so we had to sell Kanapa. It was bought by Ukrainian IT professionals. We took a €1 million hit. Today the place is called Willa Biała. It still runs on our menu, and there’s a line outside.

I don’t believe in failures. Everything is an experience. Some study for an MBA. I’m living it, risking real money. In 2016, we tried regional Ukrainian formats. I’m from Odesa, so we opened Bessarabia in Kyiv, with dishes like tartare and rapana necks. But guests wanted squid and salmon. It was a false start. A month later, we transformed it into Liubchyk, and suddenly there was a line. Clearer idea, more familiar: flounder and red mullet.

My partners and I actually ran a farm in 2012. We raised four cattle breeds to produce marbled beef for Oxota na Ovets and Vatra. We even grew a few unusual vegetable varieties, like heirloom carrots. But it didn’t work. A bull weighs a ton, but only 20% becomes sellable steaks: tenderloin and ribeye. Nobody wanted tomahawks or butcher’s cuts. So what do you do with the other 800 kilos? To make it work, we needed retail shops or a processing plant, not just restaurants. Was it a failure? I wouldn’t call it that. It was an extremely expensive lesson.

How does the average check differ between Ukraine and your international locations?

In Ukraine, checks average $4 to $4.70 at Bilyi Nalyv, depending on the city and location. In Poland and Slovakia, it’s higher, about $6.80 to $7.40, because guests order more.

When you open abroad, do you rely more on Ukrainians who already know the brand, or on locals? And do you adapt the menu by country?

The menu stays the same. Bilyi Nalyv is a cider bar, and what we serve works anywhere: hot dogs, cider, nalyvka, oysters. Most of our international locations are in Poland, where cider and nalyvka are already familiar, so there’s no need to reinvent anything. We want both Ukrainians and locals. The difference is that we communicate in the local language and tailor our brand identity to each country.

How strong is the competition for Bilyi Nalyv abroad?

In the cider category, there really isn’t any. There are no well-known cider bar chains in Europe. That said, about 90% of our locations are on central streets, so we do compete with places offering other drinks. People can always go for beer or prosecco instead.

How do you set up your venues abroad?

All the furniture, branding, signage, and part of the equipment come from Ukraine. It’s faster and cheaper. Even under shelling, we managed to complete everything for Bialy Nalew in Wrocław in just a month and a half.

We also have a product franchise abroad. Partners make cider and nalyvka under our brand. In Poland, there’s a company that imports Ukrainian products to our locations, like ingredients for hot dogs. I’m proud of that. Ukrainian products are already in Europe, and I hope we keep expanding.

What are the biggest challenges your franchisees face?

Real estate is the hardest part. Often, they have to buy the premises out from the previous tenant. We’re talking serious money.

For example, there’s interest in a Bilyi Nalyv in London’s Soho, where the lease transfer starts at £1 million. It’s a prime location. In central Prague, it’s around €180,000. In Warsaw, about €80,000. These are serious investments. We crunch the numbers with our team, give our partners our take, and they make the final call.

Every country has different legal requirements, especially for alcohol licenses. In Poland alone, the rules vary by city. Finding reliable staff is another issue. Every location needs a solid core team. A lot of our staff at Bilyi Nalyv are students, which isn’t always reliable.

Do you manage teams differently in Ukraine versus abroad?

No. These are Ukrainian teams. Ninety-nine percent relocated from Ukraine, from managers to servers. Business is part of my life, so my core values: trust, belief, love are written into the company’s values.

Your international locations are all affordable formats. Any plans for upscale places, like Kanapa?

If there’s demand for a franchise, then yes. But we don’t plan to invest our own money.

3

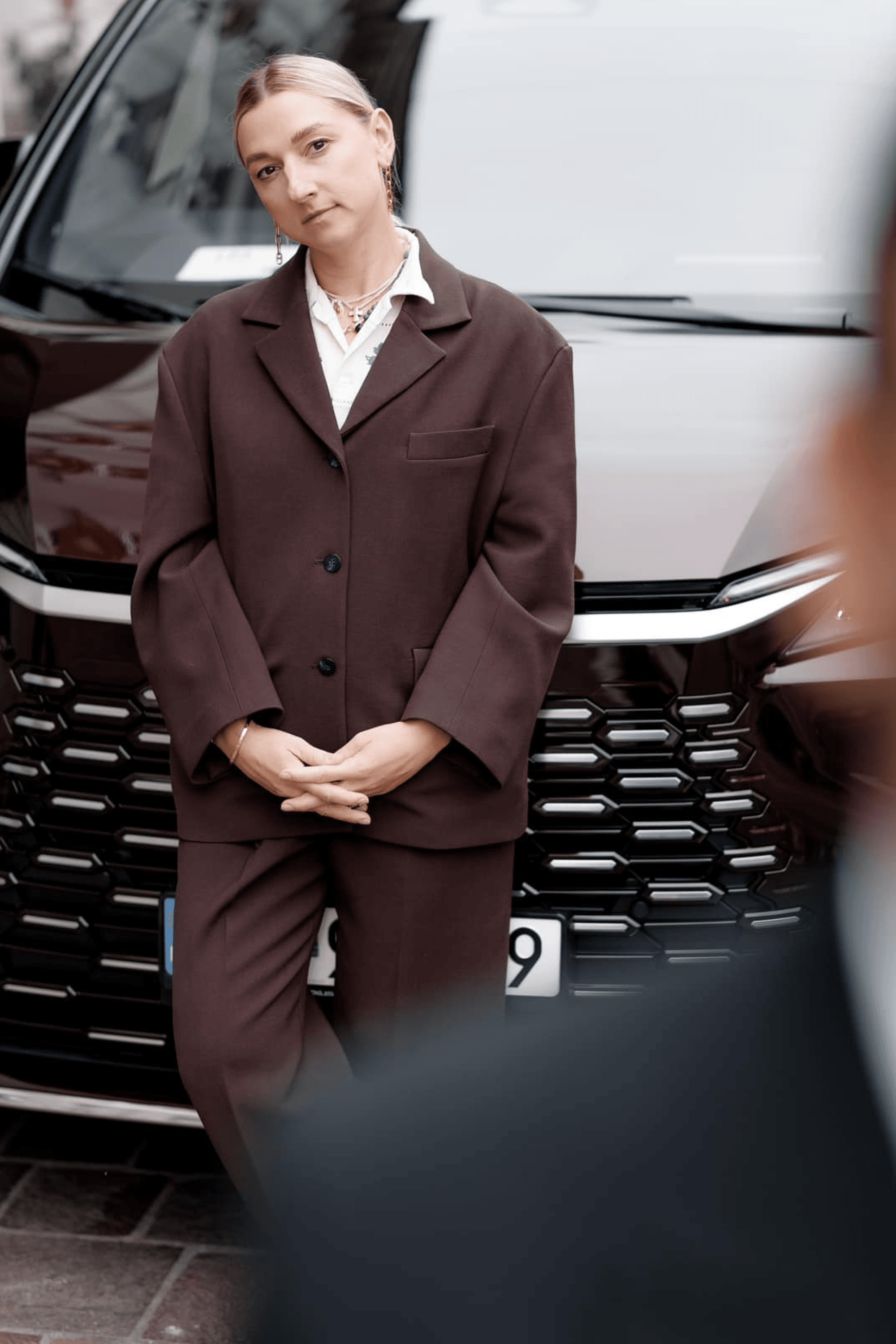

In January 2025, your former husband Dmytro Borysov left the business, and since then you’ve been running GastroFamily on your own. Do you feel being a woman in a leadership role helps in negotiations, or makes them harder?

In theory, business shouldn’t have a gender. But I’ve been in the restaurant industry for 24 years, and as a woman with five children, I’ve faced sexism constantly.

Back when Dmytro and I were business partners, I took care of all the day-to-day work.Yet some men at meetings would insist on speaking only with him. We’d come together, and they wouldn’t shake my hand or would act as if I wasn’t there at all. I wasn’t there as a wife or a mother of five children. I was the company’s operating CEO. And Dmytro often didn’t have answers to day-to-day questions, because he wasn’t involved in that work.

Now I see things changing for the better. In Ukraine, a woman can be anyone: prime minister, truck driver, crane operator, just like after World War II. Sexism hasn’t disappeared, but there’s less of it.

After Dmytro left, some restaurant critics wrote that GastroFamily wouldn’t be the same. How did you deal with that skepticism?

I didn’t read those posts, but my team did. We dealt with it because GastroFamily hasn’t been about Dima and Lena for a long time. It’s about the team. And nothing changed there. At our newer places like Mushlya, BPSH, and Bilyi Nalyv, which have been around for about seven years, guests don’t even know who Dima and Lena are. They come for the product. And the product hasn’t changed.

Of course, it was a difficult period. But I believe Dmytro and I handled it well, both as business partners and as former spouses. I’m deeply grateful to my team. I know competitors tried to poach our staff during that vulnerable time, but they stayed. People show who they really are in times of turbulence. I’m proud of the team I built. They stood by me. I have nothing to be ashamed of. If anything, I’m more confident now in my values, my team, my strategy, and what I’m doing. Our company is first and foremost about people. That’s why nothing has changed.

How do you see GastroFamily developing over the next few years?

It is an umbrella brand with several different directions. First, our own restaurants. Second, the concepts we grow through franchising. Then the educational, charitable, and social projects we run. We also have our own food delivery service, which will shift to a different model in September 2026.

We’re developing two new restaurant concepts that we’ll franchise as well. I’m confident they’ll work once we’ve tested and built the systems.

I’m also stepping outside GastroFamily to launch my own strategic consulting agency. It will be called Sapunova, my maiden name. My team and I have been advising entrepreneurs for years, and now I’m making it its own business.

For the past six years, I’ve been writing a book. I turned in the manuscript in late October 2025. It’s a major project, a manifesto for women. It’s also called Sapunova, about 200 pages across nine chapters. It tells the story of my 41-year journey: my experiences, thoughts, emotions, and what I’ve learned. This won’t just be for Ukraine. I want it to reach Europe and the US too. I’m not interested in simply selling copies. What matters to me is speaking about women and helping them.

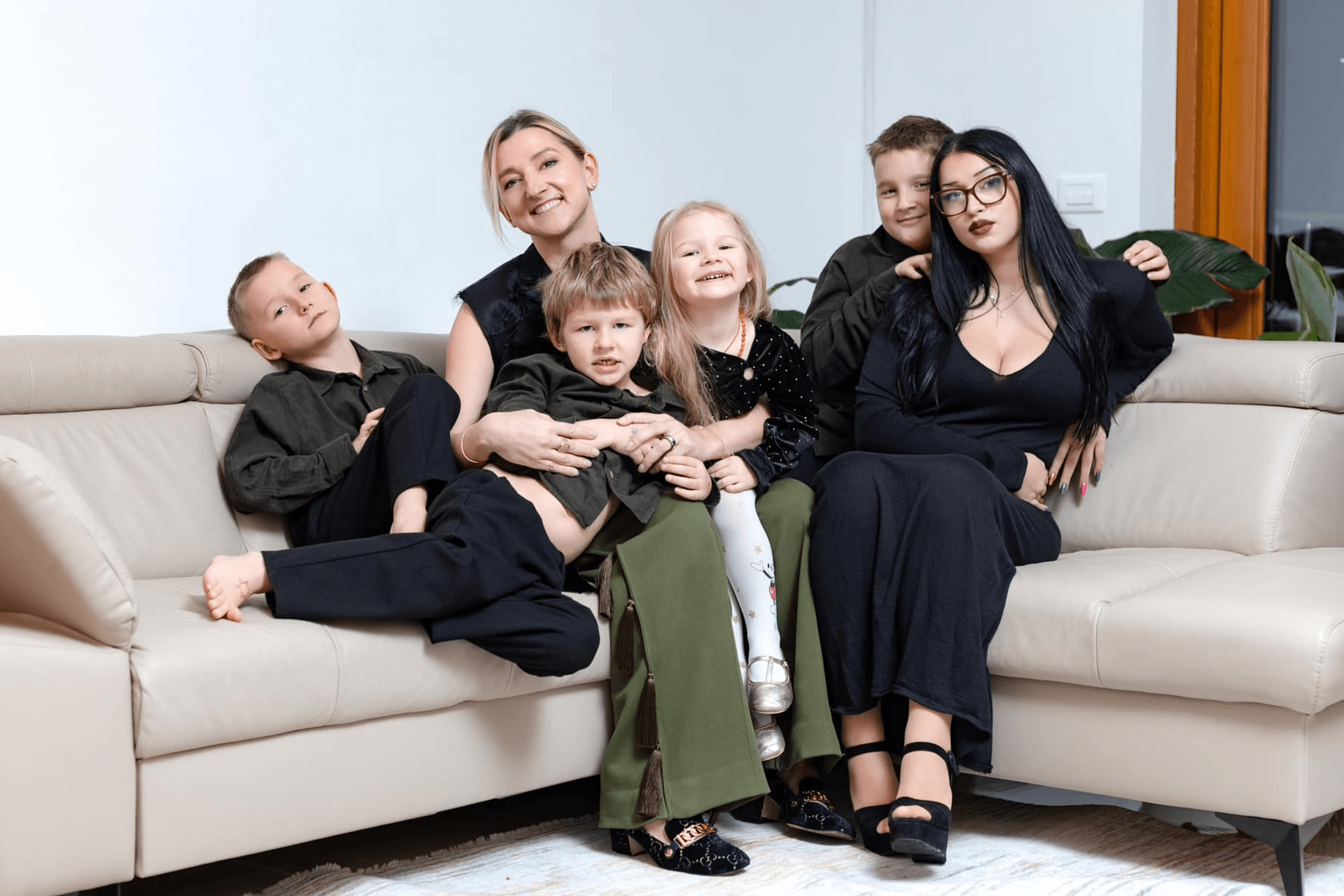

You run a large company and are also a mother of five. How do you manage it all? Is there any kind of balance between business and motherhood?

My life is made up of family, business, and my own interests. Right now, I split my time between two countries. Half the month I’m with my children in Ljubljana, Slovenia. The other half I’m in Ukraine while they stay with a nanny and their grandmother. How do I manage? I don’t have a choice. What’s the alternative? My children are the most important projects of my life. People often ask my parents, “Did Lena always want a big family?” No, it wasn’t planned. But Dmytro and I were deeply in love, and our children came from that. It was the same with my first husband. That’s how my oldest daughter, Katia, was born. She’s 16 now.

I like a scale. If it’s restaurants, then many of them. If it’s children, then many too. I know how to scale both business and family.

What helps me most is structure. I’ve had it since childhood. I trained professionally in track and field and got used to living by a schedule. I work every day, including weekends when needed. But I always make time for myself. I train at least five times a week.

The most interesting part of life is only beginning. There are so many new challenges in business. I’ve never been this scared and this excited at the same time. But I know I’ve got this.

What’s your advice for Ukrainian restaurateurs going international?

First, just start and do it. Second, learn and go through every single stage of the business yourself. And third, don’t be afraid. The scariest things are captivity and death. We can handle everything else.