The Ukraine Global Scholars (UGS) charitable foundation has existed for over a decade. During this time, it has helped hundreds of Ukrainian teenagers enroll in prestigious foreign institutions, including Harvard and Yale universities. Yellow Blue asked the foundation’s president, Julia Lemesh, and Brandeis University student Sasha Lintovska to share how the foundation operates.

- Julia Lemesh, Harvard alumna, foundation volunteer (2015–2019), and President of the foundation since 2019:

We select the most talented teenagers and help them gain admission to top boarding schools and universities worldwide—from the US to the UAE, Germany to Qatar. While tuition at these institutions costs hundreds of thousands of dollars, the schools provide generous scholarships. Our teachers are volunteers and alumni from previous cohorts. We encourage all participants to remain active in volunteering. This includes working at our annual summer camp, managing social media, supporting marketing campaigns, and mentoring the next generation of UGS scholars. We also find host families within the Ukrainian diaspora for short breaks and regularly host events to help young people build professional networks in Ukraine. Currently, we have nearly 200 volunteers and a professional team of nine, most of whom live and work in Ukraine.

The foundation launched in 2015. Following the Revolution of Dignity, we wanted to find a way to support Ukrainian youth. Looking at the educational market, we realized most opportunities were geared toward Master’s students. That is why we decided to focus on teenagers aged 14 to 18. We started with $7,000 of our own funds and contributions from close friends and family. In 2015, 150 students applied, and we selected 13. With our help, five of them were admitted to top American universities and boarding schools.

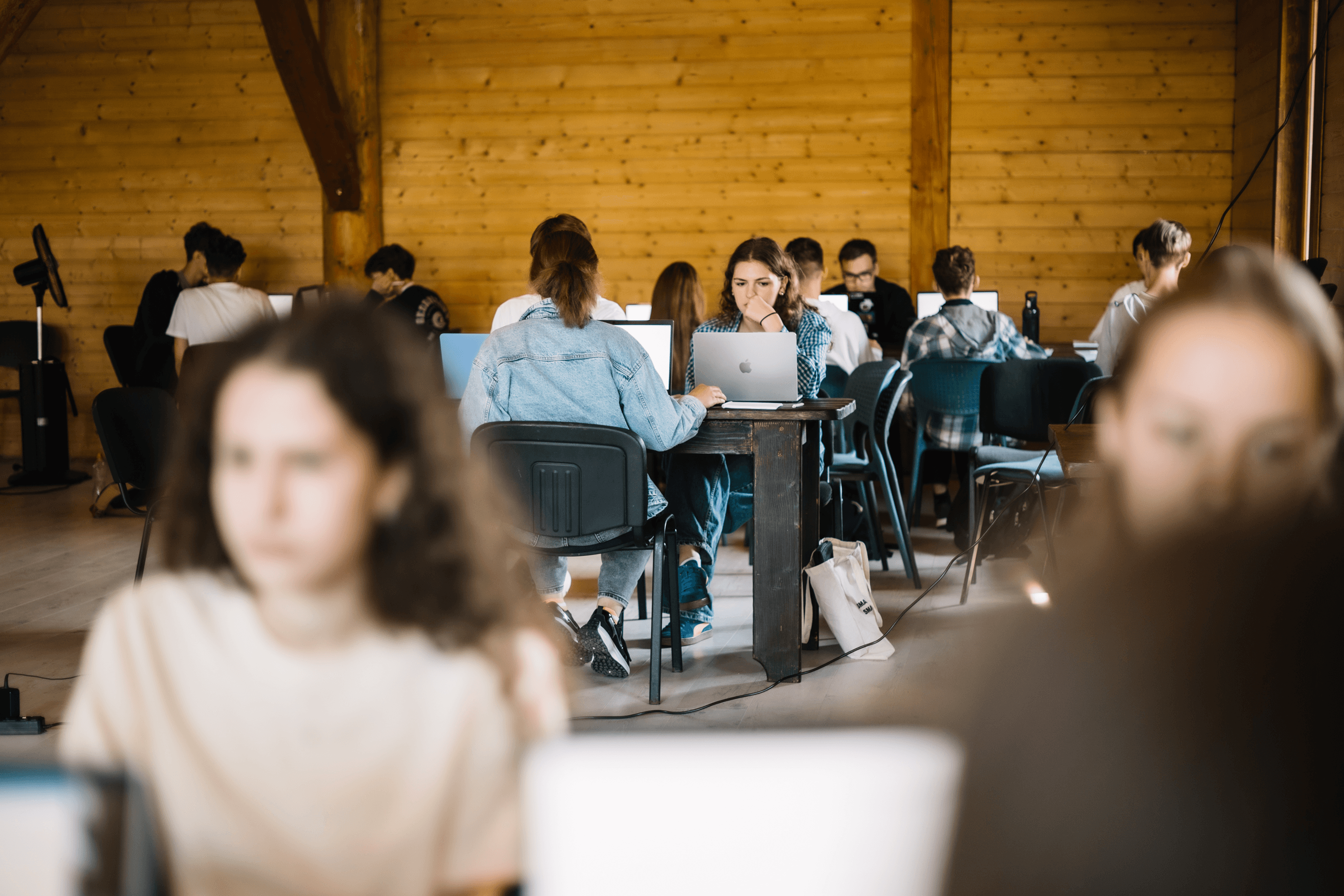

The admission process consists of three online stages: an application, English and Math tests, and an interview. Finalists must participate in a five-week online SAT school and a ten-day intensive training camp involving mock SAT tests, lectures from volunteers, and sessions with psychologists. This is followed by a year of working with individual mentors and the foundation’s team to select schools. We also offer masterclasses, workshops, and lectures from specialists on essay writing and admissions strategy.

During the camp, we continuously gather feedback from volunteers who grade homework and deliver lectures. They meet with applicants online weekly, providing strategic and tactical support.

We aim for approximately 500 applicants per year, with UGS accepting 7-10%. Key requirements include a high GPA and strong English proficiency. Extracurricular activities—such as sports, volunteering, or community involvement—are a significant advantage. We specifically support children from low-income families with an annual household income under $35,000.

Crucially, we look for students with a deep passion and clear achievements in one or more areas. Ideal candidates might be aspiring writers with published works, students who have their own startups, or those deeply involved in fields like robotics.

Every year, one to three candidates leave the program after selection. This is normal, as not everyone realizes the level of effort required during the admissions process.

Each student costs the foundation between $1,000 and $3,500. This covers preparation, application fees, and relocation—excluding the countless hours our mentors volunteer. We also provide stipends for unpaid internships in Ukraine, travel expenses to host families in the US, emergency family aid, a loan repayment fund, and additional academic resources. Thus, the final amount depends on many factors.

Historically, the US has offered generous scholarships, but that window of opportunity is narrowing. As a result, our finalists are increasingly attending universities in Europe or Asia. There are various support levels. The best scenario is full coverage—tuition, flights, insurance, and airport pickups. The lowest level might require a student to contribute $6,000–$10,000 per year, often covered by a 10-year university loan. Students don’t receive cash directly; stipends or meal plan funds are credited to their accounts. If funding is partial, we provide a small grant of $2,500, and students often work on campus or take out loans.

Program alumni are required to return to Ukraine and work there for at least five years. The foundation’s goal is for students to apply their knowledge at home, especially during the war when Ukraine faces a critical talent shortage. To ensure this, we sign a contract with students and their parents outlining all obligations.

Educating some Ukrainian children at the world’s best universities does not hinder the development of educational institutions in Ukraine; these are parallel processes. While some see “brain drain,” we see the opposite. Ukraine only stands to gain from a larger number of young people with top-tier educations and international connections. This is proven by the experience of countries like China, India, South Korea, Singapore, and Israel, which heavily support their youth studying abroad.

Currently, we have over a hundred partners, including universities, boarding schools, companies offering internships in Ukraine, and organizations providing in-kind support like Duolingo, UWorld, and Grammarly.

We are looking at horizontal growth through the Back2Impact Ukraine platform. The idea is to centralize resources for short- and long-term employment and internships in Ukraine for returning students and foreigners interested in careers here. Our goal is not just to send youth abroad but to become a center of gravity for those seeking career opportunities in Ukraine.

Ukrainians possess unique expertise in sectors ranging from defense to wartime mental health support. We have much to offer the world. Our students constantly strive to show their peers that Ukraine should not be viewed solely as a victim. For instance, our alumna Maryna Hrytsenko co-founded the Snake Island Institute in Kyiv. The institute uses practical knowledge gained from the battlefield to better understand modern warfare. Maryna frequently travels to the US with her team to share Ukraine’s combat experience.

For those aspiring to study abroad, proficiency in English or other foreign languages is vital. The earlier a child starts to learn them, the easier the adaptation. I recommend watching movies in English and finding friends to talk to weekly, such as through the ENGin program. Don’t forget extracurricular development; our partner Svitlo School offers various activities in English. Early SAT prep is also essential using resources like Khan Academy or UWorld.

A third key element is essay strategy. What do you want to tell about yourself? Study the prompts and plan your answers to reveal different facets of your personality without repeating yourself. Also, check out our free course on the Prometheus platform.

- Sasha Lintovska, UGS Alumna and currently the only Ukrainian undergraduate student at Brandeis University in Boston:

I first applied to the UGS program in 2022 when I was 15. That year, due to Russia’s full-scale invasion, the foundation extended the application deadline by a month. There were about 500 candidates, and 80 made it to the finals—more than five applicants per spot. During my interview, I talked about organizing literary evenings and playing in a band. I was involved in poetry, fascinated by cinema as an art form, and served as school president. After every selection stage, I thought it would be my last. Finalists usually undergo a six-week exam preparation program. I remember spending dozens of hours on math tests.

I had an incredible interview with a school I truly wanted to attend. Usually, interviews last 30 minutes, but I spoke with the head of admissions for an hour and a half. He said the school would be lucky to have a person like me. I was already packing my bags in my mind.

On March 10, 2022, the results were announced. It turned out I wasn’t accepted because, as they put it, I was “rowing” [working hard] but wasn’t a “rower.” The school gave preference to American students who were competitive rowers. At that point, I wondered if I wanted to apply again. I decided that it wasn’t the right time for admissions; I would take a gap year to reflect, prepare, work with film, and then apply to an even better institution. I have an amazing mentor who guided me through all these three years and supported my decision to postpone the process.

I realized that I could achieve more in Ukraine during that time than in the States. Indeed, I got to know myself better, visited different countries, presented our projects, and worked with the Educational Human Rights House in Chernihiv on documenting Russian war crimes, among many other things. I had no desire to leave at any cost; I consciously sought a high-quality education. We have an example of a girl who didn’t get into a US school and is now studying at a Ukrainian medical university. At 18, she is already collaborating with Ukraine’s top neurosurgeon. To gain such practical experience in the US, one would need several years of study. She’s doing it now and wants to work at home country. UGS supports people like her.

My strategy in the following years [after the first unsuccessful attempt] was simple: to live my life well enough so that if I didn’t get in again, it wouldn’t matter much. Also, I had the largest mentoring team in history because all the alumni from previous years were rooting for me and helping with everything—essays, financial documents, you name it. By then, I was too old for boarding school, so I applied to universities. For admission, you need good grades in all basic subjects and a lot of paperwork: financial documents, teacher recommendations, a resume, activity descriptions, and essays. You have 600 words to show how you think, explain what shaped you as a person, and what perspective you will bring with you.

In March 2025, five days before my 18th birthday, an acceptance letter arrived from Brandeis University. That same day, I received a dream job offer in Kyiv—in marketing for a film streaming service. During the three years I spent applying through UGS, I didn’t have an “American dream”; I had actually grown disillusioned with the US and was super skeptical. I thought: “I’ll go to work, and we’ll see if they give me a visa, if the funding is okay, or if there are any 'buts'—there are a hundred million things in the world that can go wrong.” But the university provided a full scholarship covering tuition, living expenses, health insurance, and flights. I got my visa two months later, traveling to Moldova for it. On August 20, I flew to Boston. This year at Brandeis, I’m the only Ukrainian among all 3,500 undergraduate students.

I applied to 23 universities and only added Brandeis at the last minute. As it turns out, it fits my personality perfectly. We have this incredible tradition here—putting on a play in just 24 hours. You’re given the title at 8:00 PM on Saturday, and you’re on stage by 8:00 PM Sunday. It’s wild. I only got two hours of sleep, but I ended up being the only international student to land a lead role.

The university has a system of majors and minors. I have two majors—Film and Business—and a minor in Creativity, the Arts, and Social Transformation. We explore the impact of art on sociopolitical changes in the world. I joke that I have another “minor” in promoting Ukraine, which I should list on my diploma, as I spend no less time on it than on my studies. I share a room with an American student. In my corner, there’s a Ukrainian flag, a film camera, and a lens case from the university film studio. Above my desk hangs a shooting schedule from my first film set and a poster for the film Luxembourg, Luxembourg signed by its entire team.

I organized a screening here of Mstyslav Chernov’s documentary 2000 Meters to Andriivka. In one of my classes, I spoke about the abduction of Ukrainian children by Russians, drawing an analogy with Canadian and American policies toward indigenous peoples aimed at erasing national identity. I explained that this is exactly what Russians are trying to do to Ukrainians right now.

I understand that Ukraine has incredible opportunities and a great future. Many companies dream of scaling to the US. When I return, I will be a specialist with unique experience and an exceptionally deep understanding of American society. This applies not only to film but to various fields necessary for Ukraine’s reconstruction.