Daria Kolomiec is 37. She is a DJ, host, activist and cultural diplomat, the author and producer of Diary of War. What began as an audio diary of Ukrainians during the war has evolved into documentary plays staged in theaters across New York and Washington, D.C. We spoke with Kolomiec about documentary theater, advocating for Ukraine, and cultural diplomacy in the United States.

Daria, did you have any experience in cultural diplomacy before the full-scale invasion?

Not exactly. Though in hindsight, everything was leading me there. I took part in two revolutions — the Orange Revolution and the Revolution of Dignity. I traveled extensively, performed as a DJ, and always played Ukrainian music: in clubs, at private events, when working with international artists. Even then, I was weaving it into my sets. Real cultural activism began in 2022. From then on, I wasn’t just playing Ukrainian music — I was promoting it as a code of identity.

What does cultural diplomacy mean to you?

It’s when a foreigner gains new knowledge or personal experience of Ukraine and becomes an ambassador within their own circles. I think many Ukrainian artists abroad make a key mistake: they focus on Ukrainian audiences exclusively. Diplomacy only works when foreigners respond.

How did you decide to move from being an artist to cultural diplomacy? These are very different roles.

Absolutely. As an artist, you express yourself through form — music, voice, image. Diplomacy requires a producer’s mindset: building processes, managing communication and agreements, and taking responsibility not just for yourself, but for the idea you need to convey. In the first weeks of the war, I felt a mix of rage, helplessness, and an urgent need to act. Like thousands of Ukrainians, I shouted “Close the sky” and believed NATO would intervene. It felt impossible that the largest country in Europe could be facing genocide without an immediate response. When I realized that international institutions don’t work the way we imagined, that crimes can happen in plain sight — that was when something shifted in me.

What was your plan? Did you leave right away?

For the first six months, I stayed in Ukraine. February 24 found me in central Kyiv, in my apartment. When the war began, I woke up to an explosion and a phone call. I was still recovering from COVID: weak, drowsy. For a few seconds, I lay there, wanting not to open my eyes, to hold on to the old world just a little longer.

That was when I realized I didn’t know myself. That all my previous roles, experiences, and identities were not enough for this new reality. I wrote to the owner of my favorite café on the ground floor of my building. The day before, she had jokingly said she would turn it into a shelter. She opened the café's basement to everyone.

Is that when the idea for Diary of War emerged?

Yes. I wanted to document reality. In the café basement, I simply pressed “record” and described how February 24 began for me. The second recording, at my request, was sent by Jamala, a singer and close friend. After that, I started writing to friends and acquaintances: “How are you? Where are you? What do you feel? Record a voice message for me.” That’s how I began collecting audio diaries from people around me. As the invasion unfolded, horrific events were happening in Bucha, Irpin, Hostomel, and Mariupol. I knew the world had to hear these stories.

Did you ask for permission to use and share these recordings? After all, people were trusting you with very personal information.

Of course. Every time, I explained that the audio messages would become part of the Diary of War podcast.

On what basis did you choose whose stories to share, if it’s fair to ask?

At first, from my own circle. Then through Instagram and recommendations from friends. Sometimes people themselves sent recordings. It was important to document stories from different regions of Ukraine: Mariupol, Kyiv region, Kharkiv, Kherson. The recordings ran from 10 to 30 minutes. I edited them myself. A friend in Brazil created the cover art, and another friend produced the intro for Diary of War. I started posting them on YouTube with subtitles in English, Spanish, and Portuguese. Ukrainians from around the world helped with translations. None of this was monetized.

I searched for people, spoke with them, collected the audio diaries, edited, and published them. It was real journalistic work. The people were extraordinary: Olha Bulkina, a clown who works with children at Okhmatdyt Children’s Hospital; Yaroslav Semenenko, a Paralympic swimmer from Mariupol; Olena Nikulina, the wife of Azov fighter Maksym Nikulin, who spent more than three years in Russian captivity; Marat Shevchenko, a sound engineer and musician who escaped occupied Kupiansk on a motorcycle, carrying a vyshyvanka and a vinyl record collection; Olena Bila, a deaf woman from Kharkiv; and Anna Tymchenko, who gave birth in occupied Bucha.

Who was the most recent participant in the project?

Iryna Tsybukh. She recorded her diary in 2022 from Avdiivka. We met through Instagram and became friends. Iryna was a 25-year-old paramedic with the Hospitallers Medical Battalion. On May 29, 2024, during a rotation in the Kharkiv direction, Russia killed her.

When did you realize you needed to go abroad to pursue cultural and diplomatic work?

In August 2022. Before the war, I dreamed of studying acting in New York. In 2021, I was accepted to the American Academy of Dramatic Arts and planned to spend summer 2022 there. When the invasion began, I forgot about it. I thought only about safety and the Diary of War project. Later, my friends reminded me and said, “You can go and tell the world about Ukraine.” It was only five weeks of training. I packed a suitcase with vinyl records by Volodymyr Ivasiuk and Kobza, vyshyvanky, a Ukrainian flag, and left.

What was your first impression abroad?

Shock. On Instagram, it seemed like the world was actively supporting Ukraine. In reality, people were simply living their lives: going on dates, taking vacations, drinking cocktails. Some noticed my blue-and-yellow colors and complimented my outfit, without realizing it was the Ukrainian flag. That was also when I realized how strong Russian propaganda is, how much money is poured into it, and how easily the world tolerates the aggressor. It was there, in New York, surrounded only by Americans and Europeans, that I understood how difficult it is to reach the world and how important it is to adapt the format of my stories for a foreign audience, not only on YouTube.

How did you get through to people who knew nothing about Ukraine and had no emotional connection to it?

Showing photos and videos and saying, “Look at what Russia is doing to Ukraine,” only pushed people away. They didn’t know what to say. They stepped back, apologized, or stayed silent. I realized I needed to tell my own story. I always looked confident and sharp, and I didn’t hide the fact that I had built a solid career.

I told everyone that after five weeks I was returning to Ukraine. This shocked people. They couldn’t understand why I wouldn’t stay in a safe place, why I wouldn’t become a refugee in the U.S. or Europe. That shock turned into admiration. Then I began talking in detail about Ukraine: about my observations, the diaries, and the personal stories of people. Gradually, people became emotionally engaged. Through the combination of my own story and the truth about the war, they understood that this was really happening and that Ukrainians were fighting and staying strong.

Did you organize events, or was it mostly just talking to people at acting school and around the city?

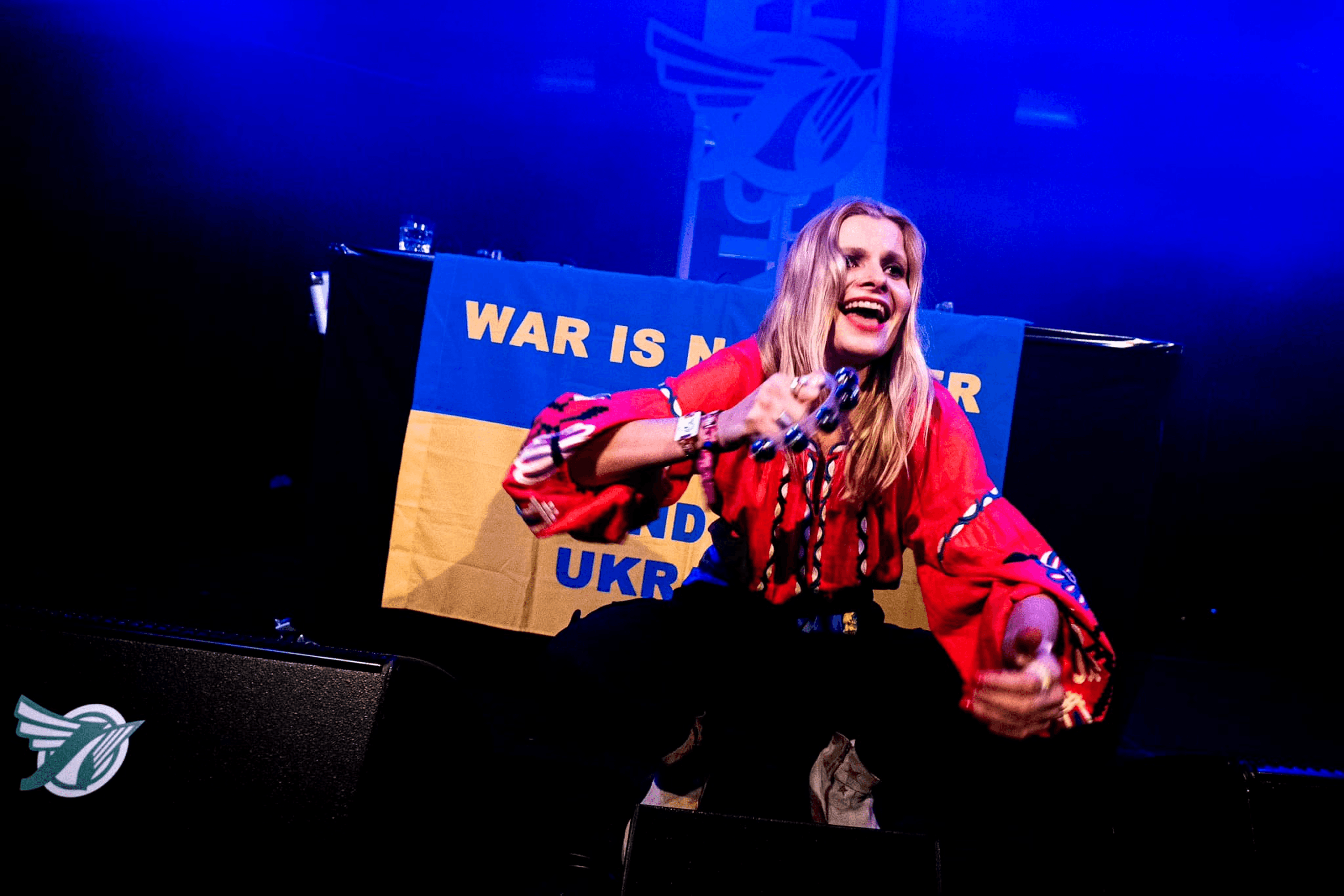

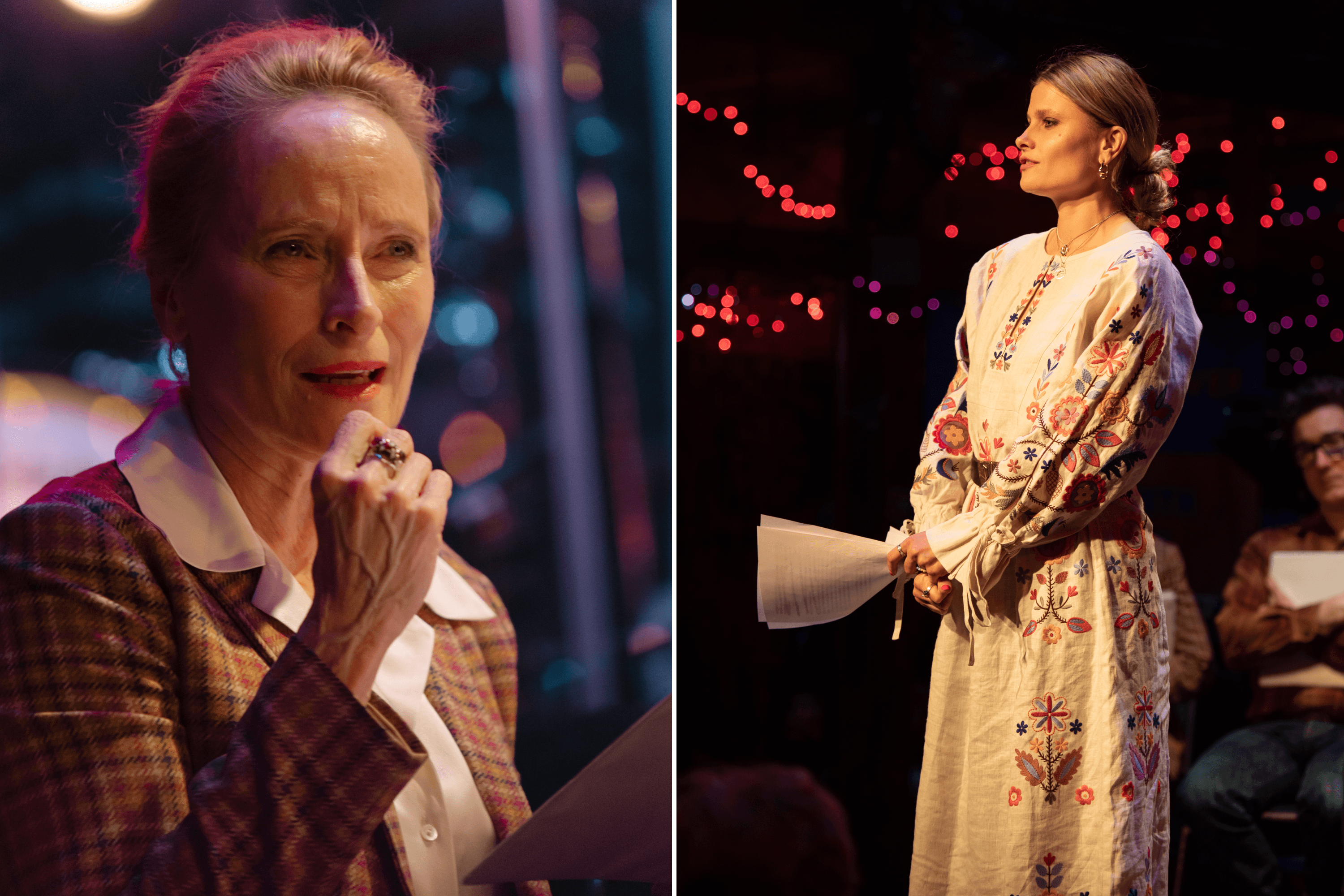

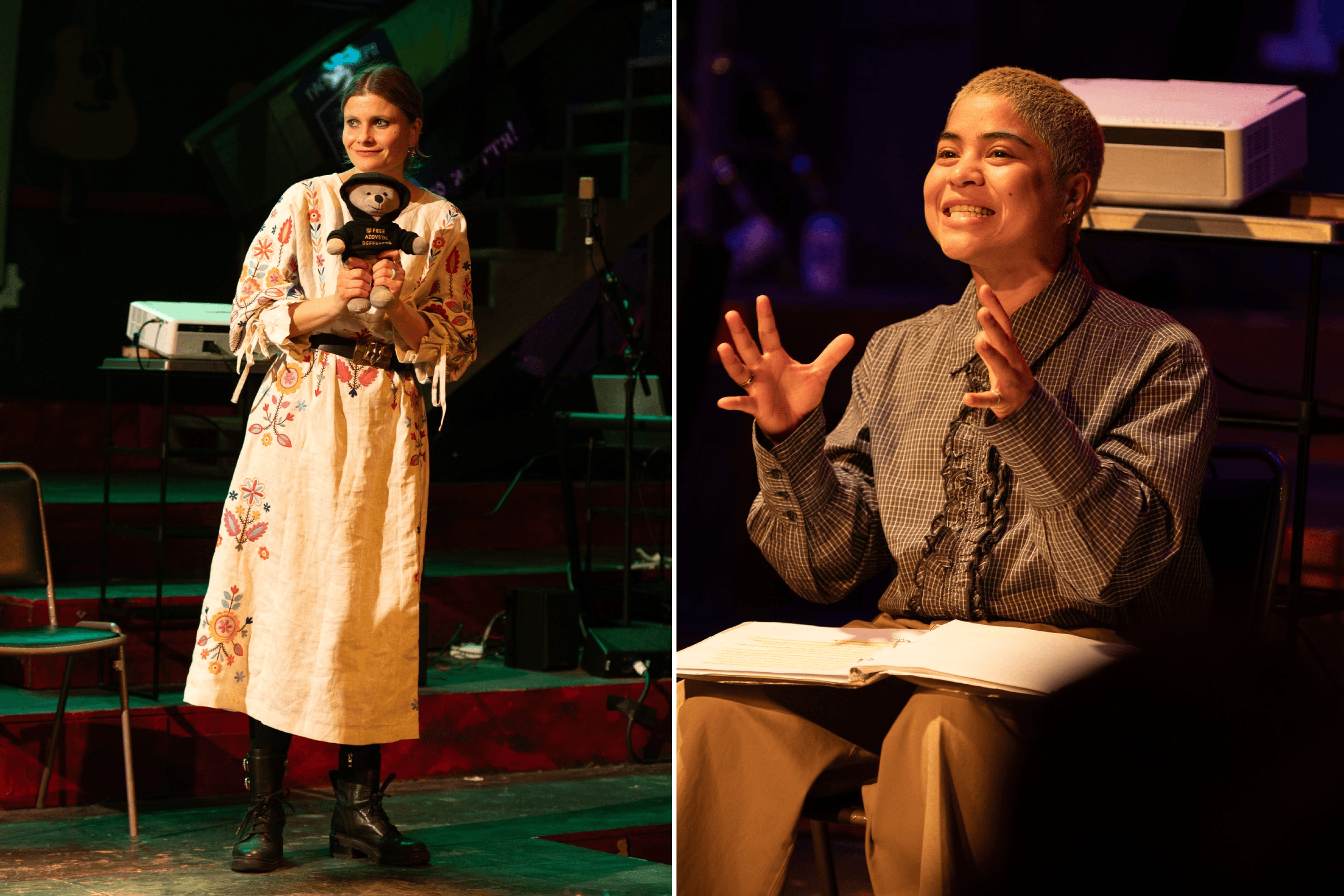

During those first five weeks, I was constantly looking for places where I could play Ukrainian music. I ended up at a large club event, where I played music by Volodymyr Ivasiuk, took the microphone, and said: “Hi guys, I’m from Ukraine. There is a Russian war in Ukraine,” while holding banners reading “War Is Not Over” and “Russia Is a Terrorist State.” This drew the attention of international media, including The New York Times. Later, during my second visit, I joined the Naked Angels community in New York, which hosts staged readings. They chose Diary of War as the first project for readings, and I felt that the material truly worked. Well-known actors joined the project, including Suzanne Shadkowski, and director Musa Gurnis became my partner. She organized the readings and connected me with actors.

At the same time, I created my own events. For example, on the second anniversary of the invasion, I organized a charity evening in New York with Suzanne Shadkowski. We raised more than $7,100 for the Women Veterans Movement.

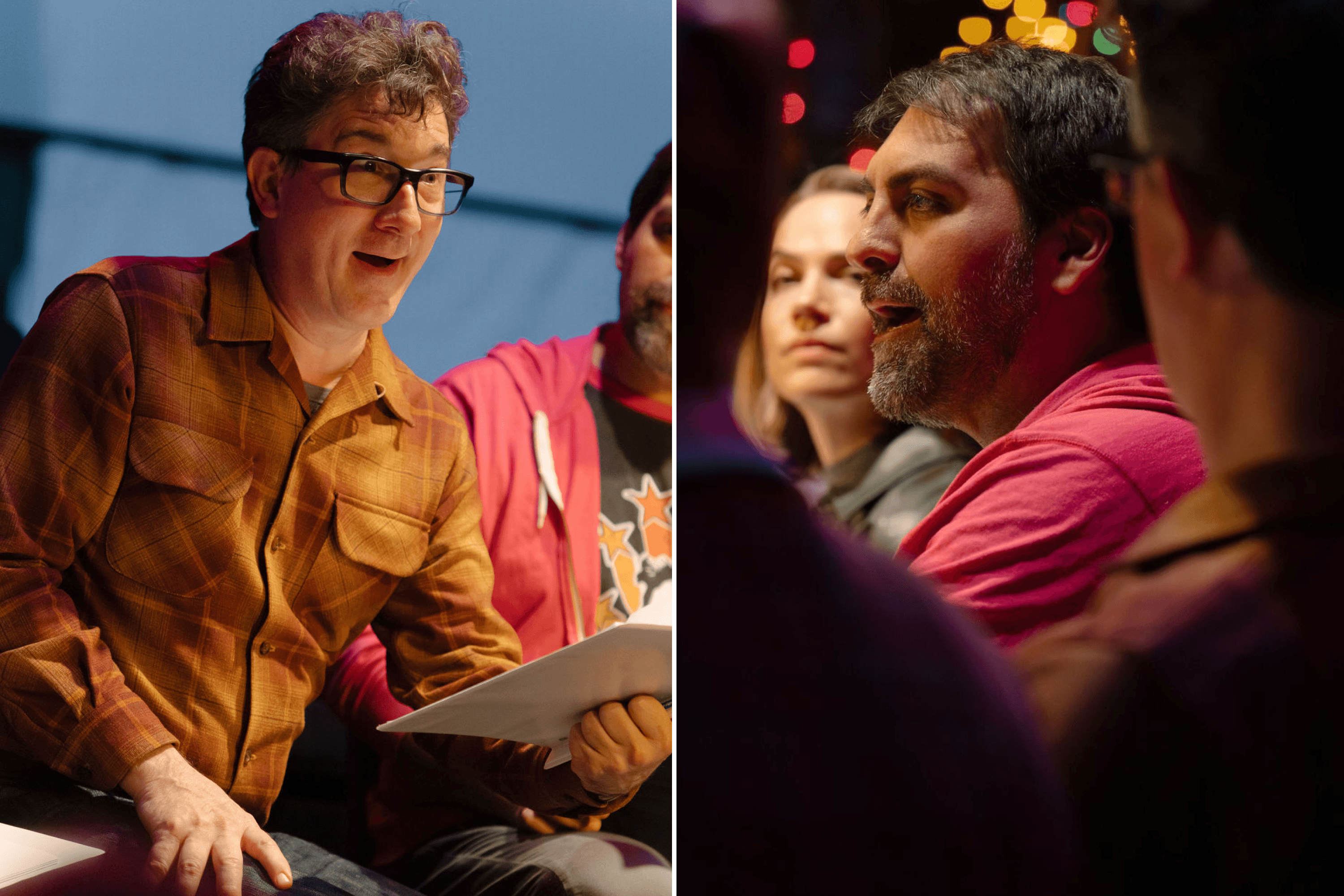

In the end, dozens of American actors read these diaries and then shared the stories with their families, friends, and artistic communities. People followed the diary contributors on Instagram, donated, and shared the stories. The impact wasn’t in the numbers. It was in how it changed people’s awareness.

How do you work with the actors?

Well-known actors volunteer their time, including Laila Robins, Ismenia Mendes, Suzanne Shadkowski, Kate Grimes, Jake Hart, Carson Elrod, Jason Bowen, and Holly Twyford. I walk each of them through the context and show how to correctly pronounce the names of Ukrainian cities and institutions. My partner is director Musa Gurnis, an American with no personal connection to Ukraine, who helps adapt the material for American audiences.

I feel a responsibility to Ukrainians as a whole, and especially to the people whose diaries we bring to the stage. Russia uses Chekhov to cover up its crimes. It would be disrespectful if an actor performing his work were to read the very next day the diary of someone from Mariupol. That’s why we have serious conversations with American artists about their role in cultural diplomacy, “soft power,” and the responsibility that comes with the material you present on stage.

This matters deeply. I see how participation in the project shifts how many actors think about their own theatrical practice. At the same time, this principled approach sometimes slows things down. We’ve turned down at least two prestigious venues for readings because they were staging Russian repertoire at nearly the same time. For the same reason, we don’t work with certain actors.

Forgive the direct question. You’ve been working almost continuously on charitable projects for the past three years. How do you support yourself? As I understand it, you travel to the U.S. two or three times a year, but live in Kyiv.

Yes. I live off savings I’ve been building since I was 18, when I started working toward an apartment in Kyiv. Now, at 37, I rent, and I sold my car to finance my work. When I return to Ukraine, I take on commercial projects and shoots to support myself. Diary of War, however, is my volunteer work.

What did American audiences react to most strongly?

Two moments stand out. Suzanne Shadkowski read the diary of Olena from Mariupol, a pregnant woman waiting for her loved one and giving birth during the war. It affected her so deeply that she said, “Why aren’t we giving them weapons?”

American veterans who performed in the readings understood the depth of the conflict. One of them said that they thought they knew war, but never defended their own land or their right to speak their native language. After reading the diary, he realized that Ukrainians are fighting for the very right to exist.

The diaries go beyond performances or fundraising for the defense forces. I also work with the press to get the truth out. After each reading, I would step onto the stage and explain what’s happening now to the people whose stories the actors had just embodied.

To be heard today, you need new formats of engagement. I’m always looking for them. In particular, we’re creating workshops for foreigners that do more than simply introduce the topic of war. They help participants transform their own experiences into documentary performance, theater based on the Diary of War methodology. This lets them carry Ukrainian stories forward, without direct pressure or moralizing.

How can Americans be convinced to support Ukrainian funds specifically? Private donations are declining, attention to the war in Ukraine is fading, and competition among global humanitarian crises is only growing.

I combine transparent fundraising with communication that resonates with American audiences. Through six Diary of War readings, I’ve sent more than $150,000 to the Women Veterans Movement and the volunteer medical battalion Hospitallers. But we can’t stop there.

Americans need to see that every donation has a concrete, immediate impact: treating wounded soldiers, buying medical supplies, evacuating people from the front lines. Fundraising for Ukrainian projects in the U.S. is extremely challenging because Americans mostly support organizations they already know, like the Red Cross or UNICEF. These are large international organizations with multiple layers of management. Their resources go everywhere, not just Ukraine, which means a donation may not reach where it’s needed most.

Russian propaganda also spreads stories about corruption in Ukrainian charities to undermine American trust.

What kinds of partnerships are you looking for now?

I’m looking for grants and partners in different countries to bring Diary of War to European audiences and show that the war is much closer than it seems. This needs funding and local partnerships: a director, actors, a producer, translation, and physical space. We also need auction items to raise additional funds during events.

How do you see the future of Diary of War?

I want to involve more theaters and actors worldwide. This keeps attention on Ukraine, raises funds, and shows global audiences that what’s happening here could happen to anyone if Russia’s aggression isn’t stopped.