Serhii Denisov was born in Batumi but grew up in Donetsk. Now 32, he began working in the industry at 19, quickly rising from waiter to sous chef. When Russia started the war in Donbas, Serhii returned to Batumi, where he received his first private commission—to create a menu for a restaurant. This launched his consulting career, which has spanned over 50 successful projects in Ukraine and all over Europe in seven years.

In 2018, Denisov turned down a contract in the Czech Republic to compete in the ninth season of "MasterChef Ukraine" instead, which he went on to win. He invested part of his winnings in training at Le Cordon Bleu in Paris, interned at Michelin-starred restaurants, and studied at the Basque Culinary Center. By 2022, he had his own establishments in Kyiv and Odesa. After the start of Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, he embarked on a gastronomic tour of Europe, holding charity dinners and promoting Ukrainian cuisine.

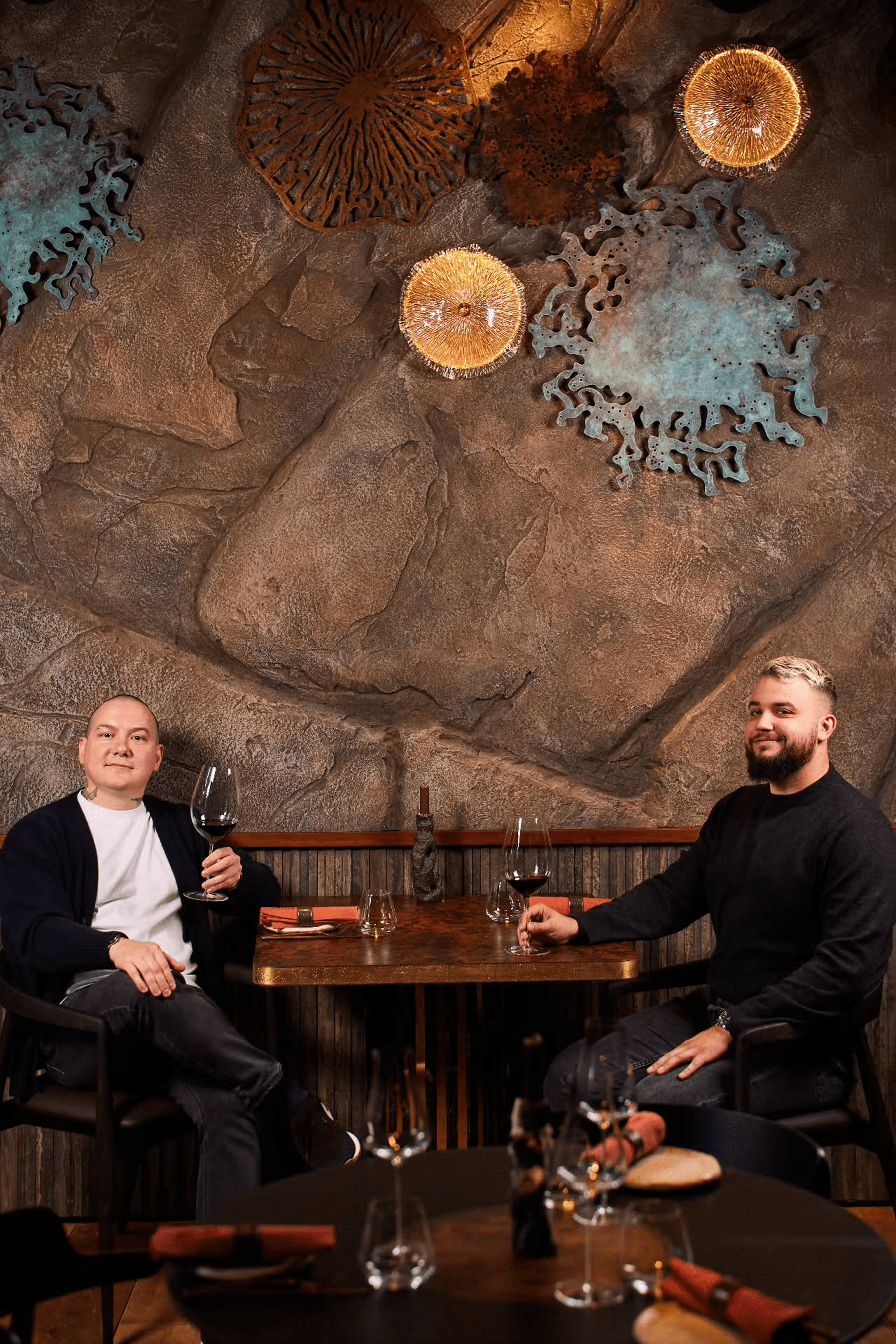

In 2023, alongside financier Oleksandr Chmeruk, Denisov founded the Mavka Group in Belgium and opened the restaurant MOLFAR in an 18th-century royal building in Brussels. The investment reached €2 million, with €700,000 being the partners' own funds. Within two months, the establishment surpassed its break-even projections and average check, announcing its goal to become the first Ukrainian restaurant in Europe to receive a Michelin star.

YBBP journalist Roksana Rublevska spoke with Serhii Denisov about how he managed to lease the royal building, secure a loan and two government grants, and why MOLFAR exceeded financial expectations just two months after opening.

Your first degree is in engineering. How did you end up in the field of gastronomy?

I listened to my parents' advice; they believed I needed a reliable profession. So, I enrolled at the Donetsk National Technical University. We studied some of the technical subjects in French. I had to learn the language from scratch, and it wasn’t easy. I made it to my fourth year but failed a few exams—the war started, and my studies were interrupted. It’s ironic that I now live and work in French-speaking countries, although my French is only intermediate.

Culinary arts always attracted me. At 19, I started working as a waiter in a premium Donetsk restaurant, and within six months, I moved to the kitchen. There, I learned to work with expensive ingredients—sturgeon, caviar, truffles, tuna, lobsters, crabs. In a few years, I became the restaurant’s sous chef. It was frequented by footballers, businessmen, and politicians.

After Russia started the war in Donbas, you left for your native Batumi, Georgia. Tell us about that period.

When the situation in Donbas escalated, I knew that under no circumstances would I work with Russians. At that time, I was offered a position as a demi-chef at the Hilton hotel restaurant in Batumi. I grew to be a sous chef there within a year. One day, a former colleague asked me to create a menu for his restaurant. Although I lacked experience, I realized I wanted to go into consulting: not just developing menus, but opening restaurants from scratch. Thanks to Hilton, I gained management skills and a huge number of contacts. In 2016, I went to open establishments in Germany, and over 11 years, I completed about fifty projects in Ukraine and Europe.

In practice, what does it mean to open a restaurant from scratch?

There are two approaches. The first is when the client already has a space, so a concept is created right for it. The second is when the idea comes first, and then a location is sought for it. If the location is poor—no parking, difficult access, or low traffic—it raises the question of whether it’s worth opening a restaurant there at all and what marketing budget is needed to compensate for these drawbacks.

My work varies. Sometimes I manage a project completely—from budget and concept to renovation, team building, and launch. Other times, I’m brought in for specific stages, like designing the kitchen or streamlining staff operations.

How did you find clients?

After working at Hilton, they started finding me. I didn’t have enough knowledge back then, so I did my first project with technologists, designers, and a chef, learning from them. With each new project, I gained more experience.

What is the income for someone who helps others open restaurants?

There’s no single rate; it all depends on the scale and format. Sometimes I took a fixed 1% of the project budget. If it’s a small project with a full cycle of work—from idea to launch—the fee could be up to 10%.

For example, opening a small coffee shop or sandwich bar costs around €10,000. This amount includes everything: design, equipment selection, menu development, staff training, implementation of the HACCP food safety system, and the launch, when everything is ready for the first day of business.

For mid-level or premium restaurants, the budgets and terms of cooperation are completely different. Owners often offer the role of brand chef—you don’t stand in the kitchen every day but manage the processes: update the menu, monitor metrics, optimize costs. You visit a few times a year and work online the rest of the time: analyzing data, checking documents, consulting the team.

Now, I only take on work with restaurant chains. A consultation costs €2,500 for two hours—this isn’t just a conversation, but a detailed, step-by-step action plan explaining where to move forward and what to focus on.

What is the role of a chef today, what falls under their responsibility? And how did participating in “MasterChef” affect your career?

In post-Soviet countries, it was long believed that a chef was just a person who stands in the kitchen. In Europe, however, they understand that a real chef is a strategist who creates demand and ensures maximum profit for the restaurant. Before “MasterChef,” my salary never exceeded €1,500. After participating, it never dropped below €7,000; the effect was colossal. My participation in the show was purely pragmatic: I wanted to build a personal brand, become recognizable outside of professional circles, and get more partnerships and orders.

In 2018, I had a signed work contract in the Czech Republic, but I backed out of it, paid a €10,000 fine, and joined the show. As a result, I won the ninth season of “MasterChef Ukraine”. I later studied at Le Cordon Bleu in Paris, partly with the TV channel’s money and partly with my own. Studying at Le Cordon Bleu in Paris, including living expenses, cost about €35,000, plus about €2,000 a month for rent, and an additional online course at the Basque Culinary Center cost another €3,500. After graduating, I received a De Cuisinier diploma. Simultaneously, I interned at two Michelin-starred restaurants.

Did you know foreign languages? How did your work abroad happen?

My English and French were weak at the time, but I communicated in a language everyone understands—the language of food. In Hamburg, I worked as a chef in a small fish restaurant opened by Ukrainians, and that’s where I first went out into the dining room to greet guests. Among the visitors were Czechs who offered me a contract: they already had their own beer restaurant and were planning to open several more, including a premium establishment with an evening menu. They needed a brand chef for the entire chain, and I was the right fit for the role.

At the time of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, you were in Warsaw. How long were you there, and why did you go to Brussels specifically?

I didn’t stay in Warsaw for long. Thanks to my network of contacts among chefs and restaurateurs, I quickly got involved in charity events with the Ministry of Culture and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine, representing the country through gastronomy. Later, I went to Brussels, London, and Paris.

As vice president of the Federation of Young Chefs of France, I organized charity dinners and culinary events. Due to the lack of official support in Ukraine, we created the Franco-Ukrainian Federation of Young Chefs in Lyon, with the support of the Institut Paul Bocuse and the city mayor’s office. Thanks to this, our team competed in the Culinary Olympics in Stuttgart, where we placed fourth among newcomers.

I had only been to Brussels once, but when I returned, I saw an opportunity to create a restaurant that could earn a Michelin star. The city has a traditional but stagnant gastronomic scene, with room for high cuisine. We held several large events, including the “Ukrainian Contemporary Gastronomy” exhibition at the Royal Museum, combining fine dining with an exhibition of Ukrainian artists and sculptors. The feedback was extraordinary. After that, I proposed to my partner, Oleksandr Chmeruk, with whom I had worked before, that we open a restaurant—and so the story of MOLFAR began.

In 2023, you registered the company Mavka Group. What does it do?

Financial and restaurant consulting—it helps open establishments, obtain loans, prepares dossiers for grants, and provides legal support. My European experience came in handy: here, you need to have a specialized chief manager or your own confirmed experience and education, which in my case, matched.

Together with Oleksandr, we also created the Ukrainian junior culinary team, which is financed by Mavka Group. This is part of our strategy—to show that Ukrainian cuisine can be modern, competitive, and that we have talented young chefs. The project is supported by the French kitchenware brand De Buyer, the oldest in its field, which is a true friend of Ukraine.

What was your vision for the restaurant at the idea stage?

From the beginning, I wanted to return to something sacred: origins, history, so the restaurant wouldn’t be like others. From the first glance at the building, I imagined an intimate chef’s table with stone, wood, and fire, where the cuisine is built on a certain primitivism and memories of the collective subconscious.

You are leasing a unique 18th-century building in the center of Brussels. How did you manage to get it?

Even Brussels residents are surprised by this story. For six months, I looked at various spaces, initially planning a restaurant with an accessible menu. One day, partners from a consulting company that works with Hilton and IHG suggested I look at an off-market location—a building from 1729, which had previously housed a Michelin-starred restaurant for over 20 years. After a fire before COVID, it never reopened: the owner tried to open a clothing store there, but failed, and put the building up for sale. He wanted to be sure I could breathe new life into the place, not just close it down in a month. After my dossier was approved, a lengthy procedure began: first, approval of the concept by the city commission, and then by the historical royal commission, which assesses how the project fits into the city center. The hardest part was just waiting for approvals, as every detail could affect the launch.

How did you convince the royal commission?

I communicated partly in French, partly in English, and sometimes with gestures and visual aids. There were no communication problems: I spoke simply and to the point. When the commission asked, “Why is this necessary?” or “How will this work?” I showed them numbers. I prepared detailed analytics—I researched foot traffic using city Wi-Fi points, heat maps, and my own observations, taking into account seasonality and the average check depending on the restaurant’s format. I also collected photos and videos to visually demonstrate which locations are truly popular.

You invested €2 million in the restaurant. What exactly were the investments for, and how much was the rent?

The rent for the space was €5,000 per month, plus taxes. The barrier to entry was high because we had to rebuild practically everything: strengthen columns, update electrical wiring and plumbing, install soundproofing and waterproofing, and redo the terrace and utilities. The initial investment was €700,000—split equally between me and my partner, Oleksandr. We covered the remaining amount—about €1.3 million—with a bank loan of €450,000 at 3.2% for seven years, two grants of €150,000 and €120,000, and additional financing from our other business projects—this was approximately €600,000.

How did you obtain government grants to open the restaurant?

We had been researching and preparing for them since September 2022. We started building the restaurant, but the project budget kept growing. We had to negotiate with contractors, working without upfront payments, to complete all the work and launch the project.

At first, seven banks turned us down, and only one agreed to issue a loan. This was expected: we didn’t have permanent documents, our status as foreigners made bankers wary, and the restaurant wasn’t operating yet. We dedicated all of 2024 to processing government grants. The community was skeptical of us at first, seeing us as newcomers “playing business”. However, when we consistently executed the project and showed results, attitudes changed: those who initially laughed were surprised by the scale and pace of development.

Did your reputation influence the bank loan and government grants?

Absolutely. The bank thoroughly vetted me and my partner; they knew about our contacts and professional achievements. They have questionnaires with detailed questions about relatives and acquaintances in influential circles; this was taken into account. My connections and case studies showed the bank that we were reliable and capable of delivering the project.

Were there many difficulties due to bureaucracy?

Yes. Countless permits were needed, and they often contradicted each other. Responses from state and local agencies could take weeks or even months. To move things forward, we constantly called, wrote, reminded, and sometimes even threatened legal action when delays became too long or we sensed prejudice due to our nationality. In Belgium, if you want to get something done, you have to be persistent.

How did you divide responsibilities with your partner, Oleksandr?

Oleksandr is responsible for legal and financial matters, while I handle the operational and creative parts—from construction and negotiations with contractors to managing the restaurant. We make all important decisions together, discussing each other’s vision. For us, partnership is about trust, a clear division of responsibilities, and mutual support when one of us needs a break or help.

What kind of cuisine does MOLFAR have?

We combine techniques from all over the world, keeping Ukrainian touch and using local, seasonal products. We adhere to a zero-waste philosophy—we use everything, even skins or bones, turning leftovers into powders, spices, and decorative elements.

The evening service is a true food theater: a set menu is served in the “Elements” hall, and a separate set is created directly in front of the guests at the chef’s table. During the day, the restaurant operates as a premium bistro for daily visits. Appetizers are served at the beginning of the set, including an amuse-bouche to awaken the appetite.

Do you still cook in the restaurant yourself?

Yes, I experiment and actively control the process. Every morning, I come in and check all stages of work: from preparation to serving. I might place an order at a random moment, check the temperature of the plates and the correctness of the preparation; I listen to how the waiters tell guests the story of our dishes.

Are there separate areas for lunch and dinner?

The restaurant’s area is about 200 m², with the main “Elements” hall taking up 70 m². There is a chef’s table with an open kitchen and a tasting wine cellar. The restaurant seats 40 guests. The space doesn’t change; the only difference is the atmosphere and table setting.

During the day, there’s natural light, lighter dishes, simpler plates and glasses, but we keep the handmade goblets and evening cutlery to add special accents. In the evening, there’s subdued lighting, exquisite tableware, wine glasses, and a more formal presentation.

The restaurant operates in a hybrid format. Why did you choose this—a bistro by day and fine dining by night?

The hybrid format emerged from our understanding of our guests and the rhythm of their lives. The location itself dictates the terms: the royal palace, embassies, national institutions, and expensive boutiques are nearby. During the day, people come for a quick lunch or a business meeting—they spend an hour or an hour and a half here and go back to work. In the evening, these same guests are looking for a different experience—calm, premium service, good wine, and gastronomic pleasure. This format allows us to combine high quality with accessibility for daily visits.

Who are your guests?

We target people with an upper-middle or high income. These are businesspersons, diplomats, politicians.

Our lunches are more accessible, but dinner is a ritual that lasts at least three hours. Guests plan this time and are willing to spend money on premium drinks. I already have reservations even three months in advance. This shows that people are willing to pay for the experience.

You previously planned for an average check of €150–€180, but now it starts at €250. Why did that happen?

Yes, that was my mistake at the beginning. We calculated the average check based only on food and pairing—about €110—and assumed guests would stop there. However, it turned out that they love expensive drinks: wine, champagne, tequila, brandy, whiskey. For example, in the last month alone, we sold four cases of wine that we buy for €80 and sell for €200. So, in fact, it’s the guests who are raising the average check by choosing premium beverages.

Is that why you expect to recoup the restaurant’s costs in 2.5 years instead of 3.5?

Yes. Our foot traffic is higher than we projected in our pessimistic forecasts, and guests are returning. Attendance depends on many factors: seasonality, public holidays, strikes, nearby construction, market days, weather. For example, when the authorities change the tram routes or close a parking lot, that’s 20% fewer guests. People are more likely to go out to the countryside on holidays or in warm weather. We adapt to this by reducing staff and procurement. Reservations help: for the chef’s table, we require full prepayment.

Is it impossible to get in for dinner without a reservation?

Correct. We have a clear rule: you can come for lunch without a reservation, but for dinner, it’s by appointment only. We prepare in advance, asking about guests' allergies and preferences. Once, three women came without a reservation: one was vegan, another didn’t eat seafood, and the third eats everything. We quickly adapted the menu, but one guest couldn’t even stand the smell of seafood. We had to replace everyone’s dishes—the evening went well, but it confirmed for us that reservations are necessary. It’s a matter of comfort and predictability: guests want everything to be taken into account—from allergens to the wishes of their children or even their small dogs.

How does the cancellation policy work?

If a guest cancels, the refund depends on the timing: two days in advance— we provide a full refund; one day in advance—50%; the day of the reservation—no refund, as the products have already been purchased and preparation has begun. We also have a “Last Minute” system: if seats become available, people nearby receive a notification and can book an hour in advance. Most people book well in advance, especially for weekends. Our guests are mainly Europeans: Belgians, Germans, Spanish, as well as Ukrainian diplomats. The restaurant’s doors are closed to Russians.

Does the Ukrainian identity influence the perception of the restaurant?

Yes, and very noticeably. Guests immediately learn about the restaurant’s history, philosophy, and team. For example, the main table is made from the wood of a destroyed house in the Donetsk region, and among the artifacts are fragments of an enemy drone shot down by the Armed Forces of Ukraine. We are not trying to shock—we are simply showing reality, the ability to rebuild, and the strength of the Ukrainian spirit.

Everything in the restaurant is unique: the dishes and furniture are handmade; no two items are the same. If something breaks, it’s not a tragedy, but part of a living history. The kitchen is autonomous: it can operate without gas or electricity, which allows us to continue service even in case of outages. All contractors are exclusively Ukrainian companies.

How many people are on the restaurant’s team, and how many of them are Ukrainian?

For now, the team is small: my partner and I are Ukrainian, and the rest of the staff are Belgian, Spanish, and Italian. There are four chefs in the kitchen, but the staff is gradually expanding. In Belgium, the social system is complex, and the law protects employees much more, so employers must select staff carefully. We don’t sign permanent contracts without preliminary checks and short-term trial agreements. Our “3-3-1” system involves two three-month contracts, then a one-year contract, and only after that, a possible full contract. This approach ensures security and transparency for both sides.

How do you plan to compete with other restaurants in Belgium or the Netherlands?

We don’t need to compete—we will collaborate. We already have two joint dinners planned with other high-end restaurants: one at our place, one at theirs. One chef is aiming for his first Michelin star, the other already has one. In Brussels, there are almost no other restaurants with our concept.

How are you perceived as Ukrainian restaurateurs in Belgium?

It wasn’t easy at first: Europeans looked down on us, as if we were some monkeys. But now they see real results: the partnership with Lanson, stable operations, and an original menu. People have started to approach us, thank us, ask deeper questions—the prejudice is gradually disappearing.

You said you want to get a Michelin star in the future. What’s required for that?

First and foremost—the chef’s style and the establishment’s story. An original idea and presentation, a high level of service. I am sure we will get it.