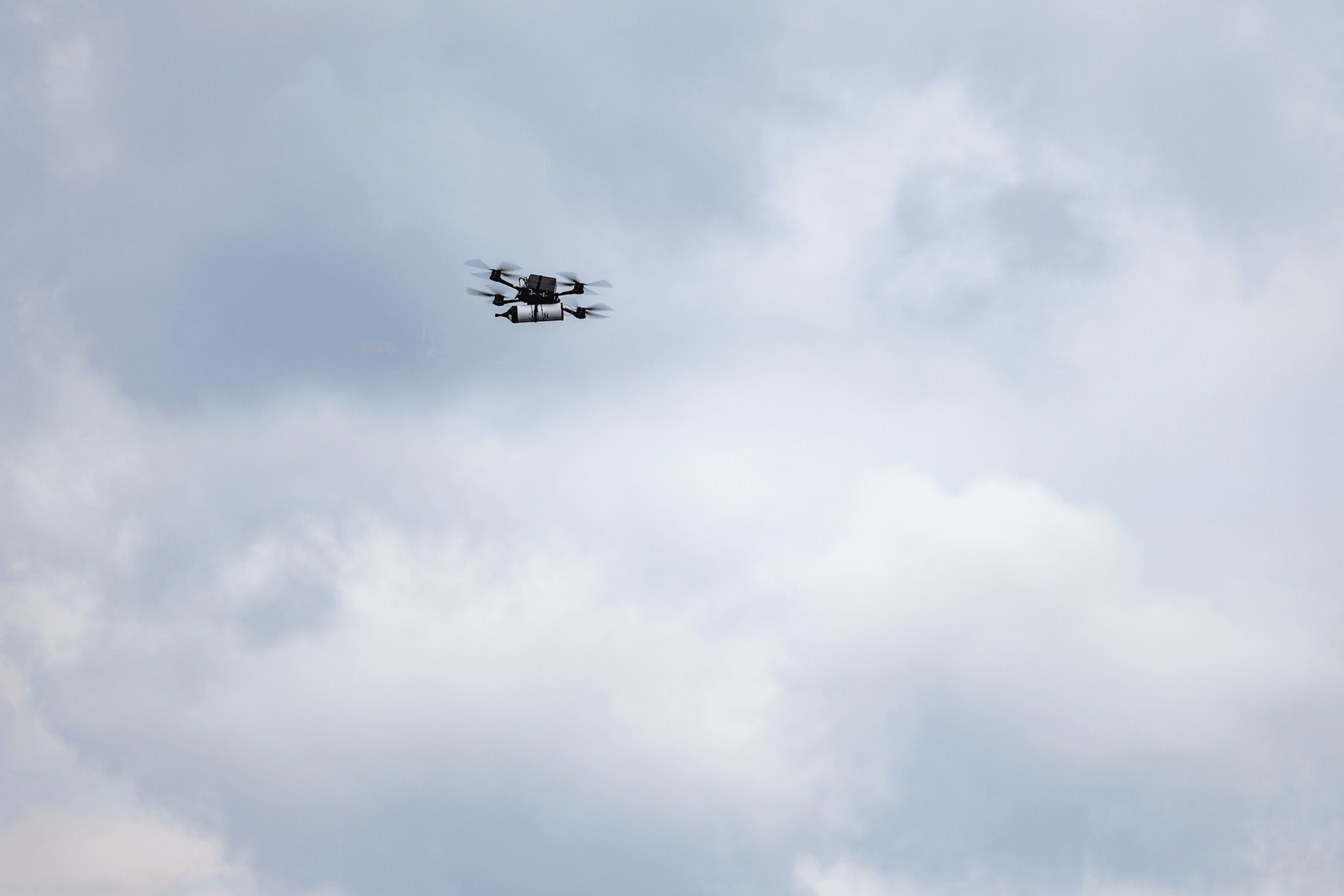

The shortage of artillery shells is pushing Ukraine to focus on domestic production of ammunition and drones. According to the Ministry of Digital Transformation, about 200 drone companies are currently operating in the country, with production in 2023 rising by tens of times compared to 2022. The trend has continued: in 2025, Ukraine is producing 900% more drones than in 2024. The combined value of government and volunteer procurement is estimated at $0.5–1 billion annually, while the Brave1 cluster has already brought together more than 3,600 defence projects, over 260 of which have been codified to NATO standards.

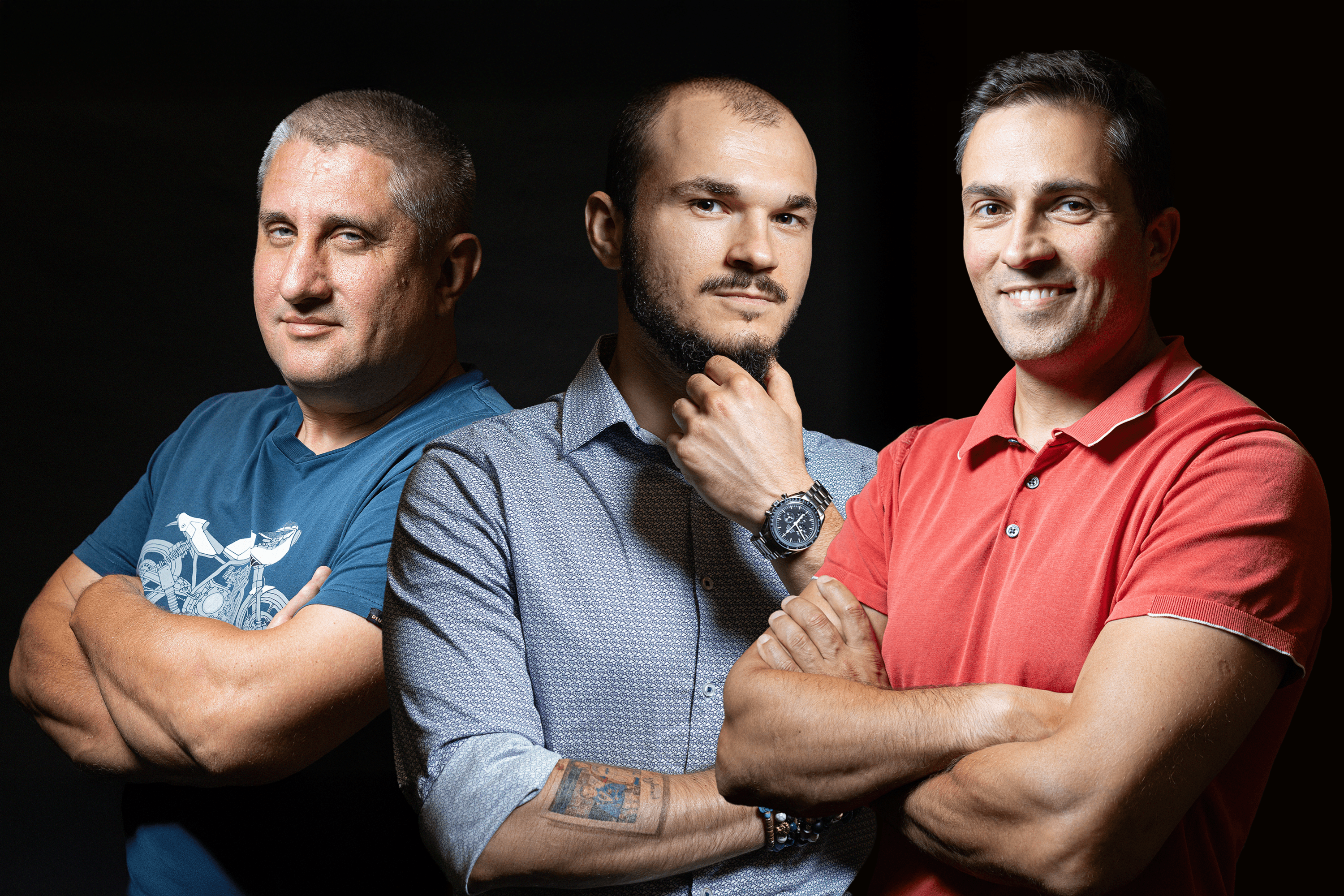

In 2022, former banker Roman Sulzhyk, along with his partners, launched the direct investment fund Resist.UA. Its goal is to strengthen the military technology sector, seize the opportunity to test new solutions on the battlefield, and ensure long-term growth after victory. The fund’s strategy is to invest in a portfolio of Ukrainian start-ups whose technologies are already in use at the front lines and have the potential to enter global markets, while also offering investors medium-term returns.

YBBP journalist Maria Zhartovska met in Kyiv with Resist.UA partners Roman Sulzhyk, Oleksiy Komlichenko and Taras Zharun to ask how Ukraine’s military-tech market works, where it is better to invest and what risks foreign players fear most.

Why did you decide to invest specifically in MilTech, and in Ukraine during the war?

Roman Sulzhyk: We founded the fund back in 2022 because we realized that Ukrainians would create many unique developments. It’s important that after victory in the war with Russia, this industry stays in Ukraine. We want strong MilTech companies to emerge, valued at tens or hundreds of millions of dollars, and capable of exporting technological products worth $1–2 billion annually.

We also want to build a new generation of entrepreneurs — veterans and young people — who operate transparently and help change Ukraine’s image in the world. Foreign investors need to see that it is possible to earn honestly in Ukraine. At the same time, we agreed that neither investors nor founders will receive dividends from the companies during the war.

How do you motivate investors to put money into Ukrainian military technologies, knowing they will not receive dividends during the war? And how do you ensure that companies actually use these funds to grow their business and not on personal needs?

R.S.: We work so closely with the companies that we almost become one family. We pay close attention to their accounting and reporting. But if someone wants to cheat, they will. That’s why we work only with those who share our values. We lead by example and communicate this to our investors.

Right now, it’s very easy to make money on government contracts, especially in FPV drone production. I’m not saying everyone there is bad, but there are many cases where people simply pocket the money. One of our major investors told us about an acquaintance who started such a company, made a profit, and paid himself $5 million in dividends. The investor said to him, “How can you do this during a war? Someone else lost out on these $5 million.”

We are fundamentally different: we don’t withdraw money, and neither do our investors. Only after victory, if the companies achieve high market value, will we and our investors profit.

Are most of your investors from Ukraine or abroad? If I’m a potential investor looking to enter Ukrainian MilTech, who should I contact and how can I tell which companies are truly promising?

Oleksiy Komlichenko: When we created the fund, none of today’s infrastructure existed yet. There was no Brave1, no hype, no, excuse me, madness like we see now. Back then we set out a philosophy: our fund was created first and foremost to develop companies that could succeed both during the war and after victory, where the founders’ main goal would be to win, not to make a quick profit.

As for the market today, venture capitalists have already entered. Everyone sees the innovations and the emergence of a large number of start-ups. There is financing from both the state and the private sector. Ukraine also has a unique advantage: unlike other countries, we have an “end consumer” — Russia (he says ironically). There is a direct front where you can immediately get feedback on what works and what doesn’t. Thanks to this, it became clear that sometimes a mass-produced and inexpensive drone is more effective than expensive and complex solutions. This is changing the very nature of war.

As for where to invest, today there are both Ukrainian and international funds, most of them registered abroad, since it is safer for investors. But we can honestly say that our fund is one of the few that has built specifically Ukrainian infrastructure: we collected Ukrainian money, received a Ukrainian license, and work with Ukrainian investors. The market is growing very quickly, with thousands of companies having already appeared.

You mentioned Brave1 — how do you assess the work of this initiative?

R.S.: It’s very important for us that there are institutional players in the market. We find companies partly through Brave1. Credit where it’s due, Brave1 does excellent work. They have created a strong ecosystem, hold Investor Days, teach teams to pitch their developments in five minutes, and award large grants of $50,000–100,000 without corruption. If a team delivers on its promises, it receives the next grants. This is exactly the right approach at the stage of creating product prototypes. I’ve attended all the Investor Days: if the first one had ten participants (5–6 from Ukraine and only 1–2 foreigners), now there are about 60, of which 55 are international.

Our model is different: we enter at the early stages because, besides money, we provide support — help with documents, recruiting, and networking. Teams become part of our “family.” We work fast: if the process with foreigners takes several months, with us a handshake is enough, and within a month, the money is in the account. Yes, we ask for a lower company valuation, but we compensate with speed and involvement. Final decisions are made by our investment committee together with the investors.

Brave1: Key Achievements and Focus Areas

- 1. Scale of developments: Over 3,600 defence projects, nearly half of which have undergone military assessment, and more than 260 codified according to NATO standards.

- 2. Funding: Since July 2023, the platform has issued over 540 grants totaling ₴2.2 billion (₴500,000 to ₴8 million) for R&D and product development. The platform has attracted over 290 investors, who invested more than $40 million in 2024 alone.

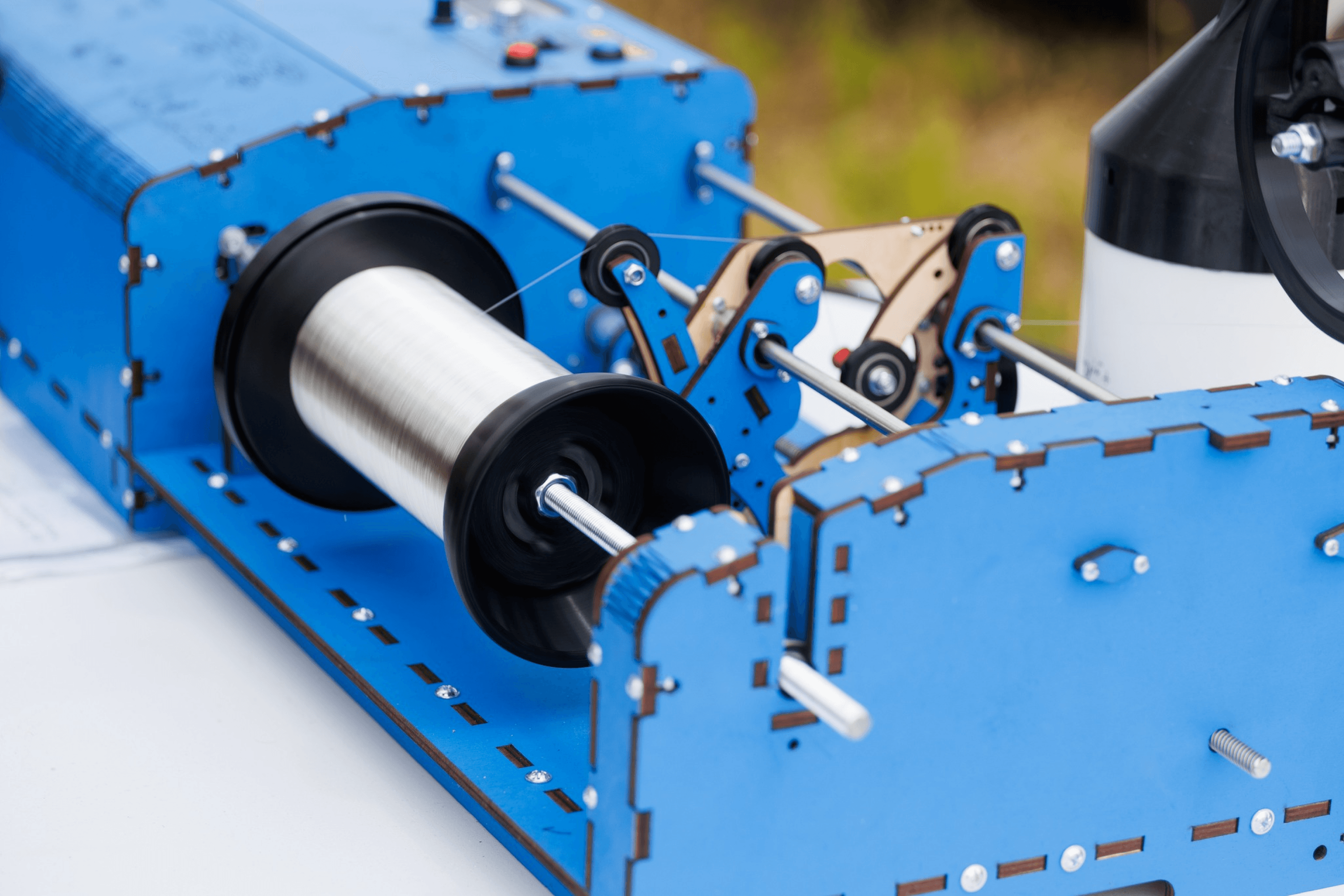

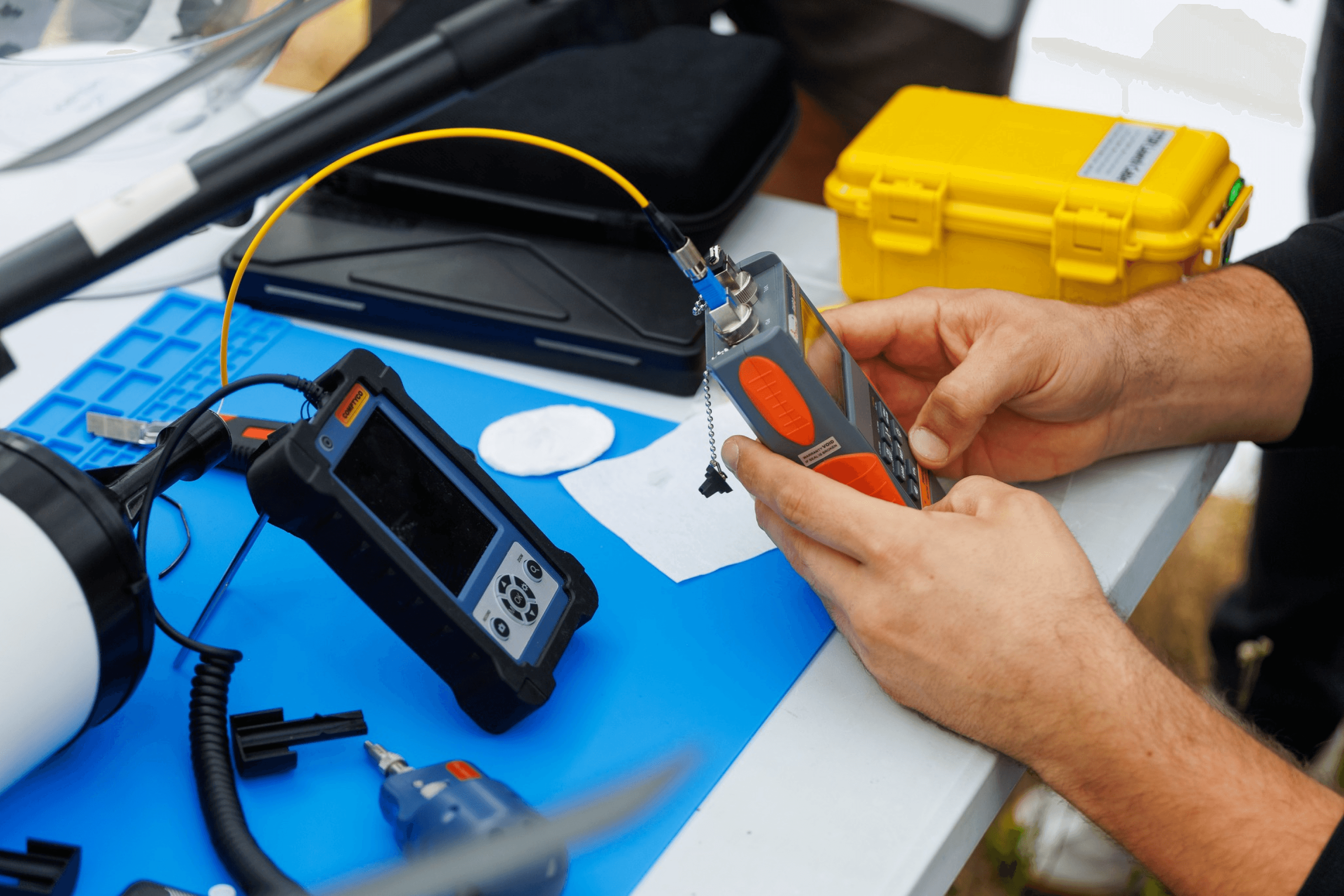

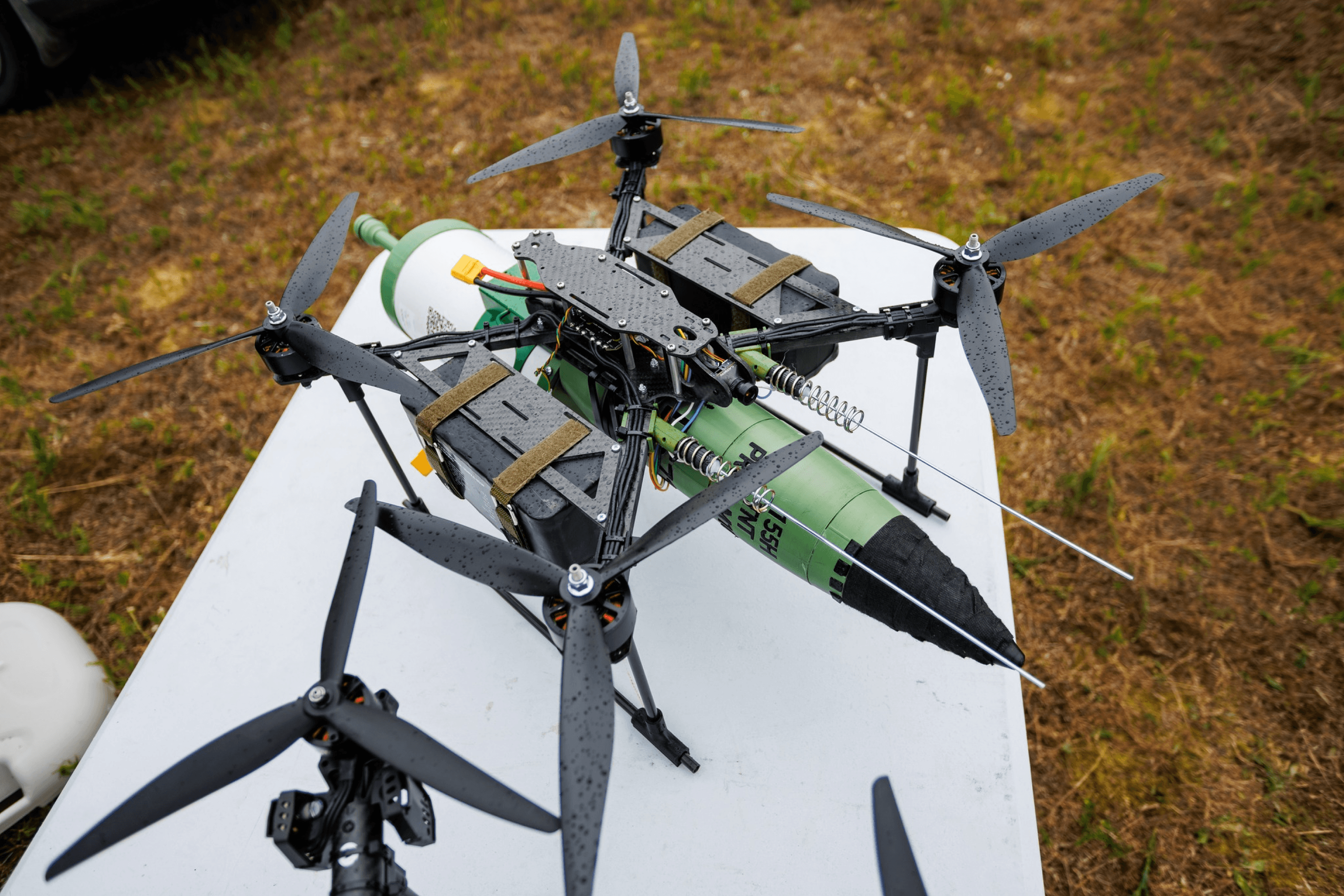

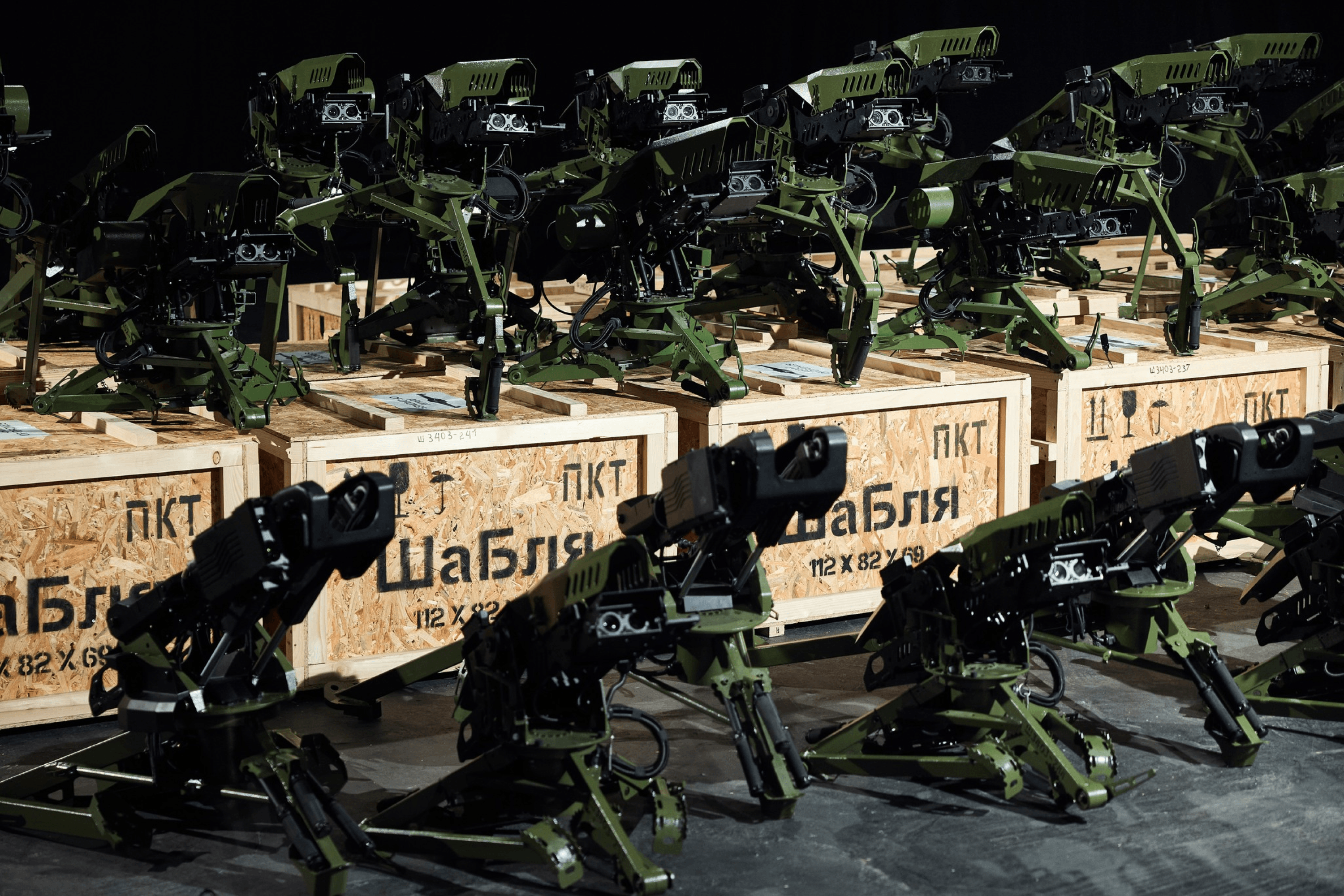

- 3. Technological priorities: Missiles, laser systems, drone swarms, autonomous strike systems, surface and underwater drones, countermeasures against Shahed drones and guided aerial bombs, guided munitions, a Ukrainian version of the Mavic drone, and electronic warfare (EW). More than 280 companies have produced over 470 developments in these areas.

- 4. Integration with international markets: Active collaboration with investors (Investor Days, matchmaking, mentorship programs), and partnerships with institutions in the U.S., France, Italy, the U.K., and other countries.

- 5. Testing and development: Regular demo days to evaluate solutions with military personnel, creation of laboratories for testing (including CRPA antennas), and deregulation of drone production (20 key decrees), allowing the sector to scale rapidly.

What conditions does your fund require of investors and companies, other than the ban on dividend payments during the war?

Taras Zharun: We must have a shared philosophy. We make the prohibition on taking dividends during the war official in our statutory documents. At the same time, we fully support market-level salaries: if the CEO of a successful company earns $10,000, $15,000, or even $20,000 depending on turnover, that’s fine.

For investors, we have two-step verification process. The first is formal KYC: passport, sources of income, etc. The second is informal: we talk with them and assess whether their principles align with ours. Roman aptly says that our fund and our companies are a “family.” To be part of this family, you need to share the same values and interests.

What money will you not accept?

T.Z.: First and foremost, Russian money.

O.K.: When we were fundraising, we quickly identified which investors we were interested in. There are certain industries and businesspeople with questionable reputations that we do not work with. I don’t see the point in naming them specifically, ut the principle is non-negotiable for us. It’s important that our investors join the fund not just for profit. For them, there’s also an emotional attachment to the industry, a desire to help, and to be part of something bigger. If we make money — great; if not — that’s also acceptable.

Now the Ukrainian military technology sector is like a wild frontier. Which companies do you actually work with?

T.Z.: In reality, companies are very different. But we don’t invest in “garages.” We work with companies at a very early stage, but it’s no longer at the level of artisanal workshops. Before investing, we always check contacts and basic processes.

I constantly emphasize, both in conversations with the authorities and with Brave1: “garages” can hold back the enemy at certain stages, but they cannot win the war. Wars are won by systems. Yes, in 2022, “artisanal” solutions helped, and that was important. But now, as Russia has shifted its economy onto a war footing, this alone is no longer enough.

So you need serial and large-scale production?

T.Z.: Exactly. In Yelabuga, for example, tens of thousands of people work there: there’s a university, laboratories, a technical school, and pilot training. It’s a full-fledged military-industrial complex. You can no longer counter it with “garage” solutions — you need a system and scale.

R.S.: We help teams move their companies beyond the “garage” stage. We create infrastructure for them: help register a legal entity, set up processes. We look for “normal” people — not those who, without a product, ask for $20 million on a $2 million valuation, with only “serial” founders and a marketing team.

Our ideal story is a guy who spent $200,000 of his own money, brought together chemistry and engineering students in a garage, and started making a missile that could shoot down Shaheds. This is a real example. My first question was, “Where did you get $200,000 at 20?” He replied, “I’m 31.” But that didn’t change my question. It turned out he’s an IT specialist, earned the money himself, and invested it. Then Brave1 got involved, we supported him too, and now his project is in the final stage of development.

O.K.: In Europe, no one will pay attention to “garage” solutions. We focus on those who may have started “in a garage” but have since grown, with a functional product and the right legal structure in place — people who understand that without systemization, they won’t survive. For the project Roman mentioned, we didn’t have to build a system from scratch, as we did with some others. That’s why it has become one of the best examples in our practice.

Once systemization is in place, we build the next level, creating infrastructure for projects that interact with each other, are well-structured, and understandable to foreign investors. To ensure companies don’t disappear after the war, they need to expand to international markets.

What else is important when selecting companies for investment?

R.S.: First and foremost, we evaluate the team and its values. We look for people who aren’t trying to make a quick profit, but who are creating products that are genuinely needed. We examine the technology or product. For example, FPV drones are trendy right now, but with hundreds of companies in the market, a low entry barrier, and high risks, we generally avoid this segment. Instead, we focus on unique technologies such as interceptor missiles, radio systems, and other solutions that the military truly needs. In each segment, there are a few players, and some have a chance to succeed and be acquired in the future by major corporations like Rheinmetall or Raytheon.

We invest in teams at the prototype stage. If we see that it actually works, we’re ready to invest. For example, an entrepreneur came to us with a laser. We said, “Okay, let’s go to the test range, launch an FPV drone, and if you can take down at least one out of ten from a distance of 100 metres, we’ll fund it.” It’s important to us that the solution is already proven to work.

O.K.: If a company already has financial performance data and plans, we conduct a full investment assessment. But above all, what matters to us is the product’s potential and whether the team is a good fit for the chosen segment.

What is the average investment in a single company?

T.Z.: On average, about $200,000.

Can you tell us about the number of investors, the amounts, and the companies you’ve invested in?

We accept investments starting at $100,000, which is the entry ticket. Our fund is aimed exclusively at qualified investors, not retail investors. Perhaps in the future, when some companies go public, there will be options for smaller investors, but right now it’s too risky, as small amounts are almost guaranteed to be lost. That’s why we have few investors, up to ten, and we’ve funded roughly the same number of companies.

In fact, we became the first in 30 years to try to create a real fund in Ukraine. Until now, the entire fund market infrastructure was built mostly not for investments, but to evade taxes and hide ownership. I remember a manager at a bank being surprised: “Everyone who registers a fund knows where they’ll invest,” and she was shocked that we were actually raising money to then select companies. This clearly shows how unprepared the system in Ukraine is for a transparent fund.

You mentioned in an interview, before the fund’s launch, that it would be small.

R.S.: Yes, it’s very boutique — just a few million euros. The initial plan was exactly that: create a small fund, close it, and then launch a larger one, either in Ukraine or abroad. Now we’ve become serious players, and partly due to the peculiarities of Ukraine’s fund market infrastructure I mentioned earlier, it became clear that the next fund really needs to be established abroad.

It will be significantly larger — $20–50 million, possibly up to $100 million. There, we’ll work with more mature companies that already have a product and real revenue. Right now, we’re choosing the jurisdiction where we will launch the fund. This will give investors proper rights and transparent valuation. We’re open to dialogue and collaboration, including with the Ukrainian diaspora. You can easily find us on LinkedIn.

How do you choose the jurisdiction where you plan to launch the fund?

O.K.: We’re considering the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Ireland, Liechtenstein, and Estonia.

R.S.: These are standard European jurisdictions — not the Cayman Islands, which are more geared toward American investors. In Europe, a new system is taking shape, and real tectonic shifts are happening.

Why, for example, have Rheinmetall’s shares doubled? Previously, European state funds couldn’t invest in MilTech. Now, due to Europe’s massive rearmament and the war in Ukraine, they can invest in Dual Use companies — so-called “dual-purpose” firms. If a company produces a product that can be used in both military and civilian spheres, it’s considered dual-use. This effectively paves the way for investment.

Of course, this market carries the risk of inflating into a “bubble.” European-Ukrainian MilTech will grow very rapidly in the coming years, but inevitably some companies will disappear. I’ve already seen this in New York: a company valued at $1 billion went bankrupt just three months later. Similar stories will happen here too.

What’s really important is this: even after the bubble bursts, the strong players will remain. Out of the “internet bubble,” companies like Apple, Google, and many others emerged.

Likewise, we hope that MilTech companies in Ukraine will emerge that actually operate, export products worth several billion dollars a year, and create and create jobs here. That is our main dream.

Is the state the main buyer right now?

O.K.: Mostly, yes, but it depends on the product. For example, components like antennas may be purchased by other drone or reconnaissance aircraft manufacturers. So, the direct client is private, but the end customer of the finished product is usually the state. There are several models: volunteer funds that buy large batches using business contributions and donations; military units, for which procurement is handled by the Ministry of Defense, the Defense Procurement Agency, the Ministry of Digital Transformation, or the State Special Communications Service; municipal budgets that allocate funds to specific brigades; and foreign donors who directly fund units. There’s also a “Danish model,” where foreigners buy equipment from local manufacturers for Ukrainian troops. There are many variations, but the bottom line is the money ultimately goes to the defense sector.

R.S.: Another important point: billions are currently being spent on defense procurement in Ukraine, but after victory — or even a ceasefire — procurement volumes will shrink dramatically. The market will undergo a major transformation. That’s why we don’t invest in companies that earn only from government contracts. It’s not a bad business, but we take a strategic view: the requirements for a company receiving large government contracts are very different from those for a company aiming to compete successfully on the global market. So those who are currently doing well selling to the state won’t necessarily become winners in global competition.

How do you know that an idea is valuable not only now but will also work after the war?

R.S.: It’s always a matter of experience. There’s a joke: “How do you make a company successful? Two words: good decisions. How do you make good decisions? One word: experience. How do you get experience? Two words: bad decisions.” The best example is a company that came to us in 2023 with what was, at the time, a fantastic idea. I even advised them to focus on a single product. They made it, and it was very well received on the front line. I could have invested at the start at a $2 million valuation, but I didn’t. By the time I returned, their value was already $8 million. In the end, they raised €1 million from foreign investors, and we missed the opportunity. This shows that we’re not all-seeing; we learn on the go, trying to “feel with our fingertips” what works.

O.K.: And we have a lot of ‘fingertips’: we communicate with military personnel and end users, and we created Resist Hub under the fund, where current and former soldiers with expertise and contacts work. They help to verify products. When a new idea emerges, we see which experts can evaluate it, organize a meeting and check it. This is how we determine whether a product is promising.

Can things like weapons testing ranges or expert services be promising investment opportunities?

O.K.: A startup approached us with military rations — MREs and other products. And not just for the army — it’s a huge market. It’s very promising because it’s export-oriented. Just as Ukrainian manufacturers of body armor and gear have proven to be better than American equivalents, food producers could also become the best. It’s not just about technology; it’s about every niche.

T.Z.: The key thing is that there’s an end consumer.

Roman, in one of your interviews you mentioned a conversation with a potential Lithuanian investor. What are the main concerns foreign investors have when considering investing in Ukrainian MilTech, and do our investors share similar concerns?

R.S.: For Ukrainian investors, it’s simpler: we operate in hryvnias, and they can see the potential in assets that may grow even in dollar terms. For foreign investors, it’s more complicated because of currency controls. One Lithuanian said to me outright, “I’m afraid to invest in Ukraine.” That’s why we created the fund — so investors understand the risks right away. If you transfer $100,000 today and change your mind tomorrow, the money won’t come back; the National Bank of Ukraine won’t allow the payment. It’s a one-way street — investors stay with us until victory, which is exactly what foreign investors worry about most. At the same time, we see strong interest and are already working on creating a separate fund for them.

By your estimate, how many companies are currently operating, and what is the total volume of money circulating in Ukrainian MilTech?

O.K.: The amount of money can be counted based on government procurement. About $50 million has already been confirmed.

R.S.: We expect investments in startups at the $200–500 million level, plus large-scale projects. For Ukraine, this is a significant figure — even $0.5 billion in MilTech is a substantial contribution, considering the average annual FDI is $3–4 billion.

How do you see the market changing after victory? Where will companies be able to export their products, and how many will survive?

R.S.: First and foremost, exports need to be allowed — and they definitely will be. Europe’s rearmament will rely heavily on Ukrainian know-how. But only companies that can work in partnership will survive. We ourselves invest as minority stakeholders, and this is an important test: if a founder is ready to collaborate honestly with a partner for 5–10%, that’s a strong signal for major investors. We’re essentially teaching companies that partnership is about trust and long-term stability.

After the victory, Ukrainian manufacturers will need to establish similar partnerships with Western corporations — either in a 50/50 format or via partial buyouts, where the founder retains 20%. Only those who prove their reliability and ability to integrate into global supply chains will have a chance to survive. Few purely Ukrainian players will remain.

You mentioned that your fund, like others, helps companies with systemization and partnerships. Are there many similar funds in Ukraine, and do you collaborate with them?

O.K.: Yes, we have joint investments with other funds. For example, in two projects, we’re working alongside a colleague we previously worked with at an investment company. We can easily meet or call to discuss deals. It’s not about competition — if someone else wants to join a deal, that’s only a plus. That said, there is some competition: the higher the demand, the higher the offer.

R.S.: There are enough funds overall; some have Ukrainian founders but are registered abroad. Purely Ukrainian, we’re essentially the only ones. A very active fund is D3, into which Eric Schmidt invested. He quickly recognized MilTech’s potential and has the resources to involve global experts in product development.

The infrastructure is growing, and new players are emerging. For example, a European fund we also collaborate with runs bootcamps and hackathons, selects projects, and invites startups, manufacturers, and other funds to joint presentations and networking on the final days. This is a classic example of coopetition, combining collaboration with competition.

Your fund has been around for three years. Have you made any mistakes?

R.S.: We’ll find out about our mistakes only after a few years. So far, all the companies are afloat; there isn’t a single one we would have needed to close.