Beykush Winery is a wine estate with a decade-long history, situated on Cape Beykush in the Mykolaiv region, where the Black Sea meets two estuaries. Although the Russian-occupied Kinburn Spit lies less than 20 kilometers away, the winery continues to thrive: planting new vineyards with unique varieties and exporting its wines to 10 countries worldwide. Yellow Blue journalist Artem Moskalenko sat down with Beykush Winery CEO Svitlana Tsybak to discuss the history of the wine house, the challenges of operating near the frontline, and the evolving global demand for Ukrainian wines between 2022 and 2025.

I have been in the wine industry since 2007, starting my career in wine imports. In 2013, I met the founder of Beykush Winery, Eugene Shneyderis, at a tasting he hosted in Kyiv. Eugene invited me to join as an external consultant, and two years later, I became a full-time member of the team.

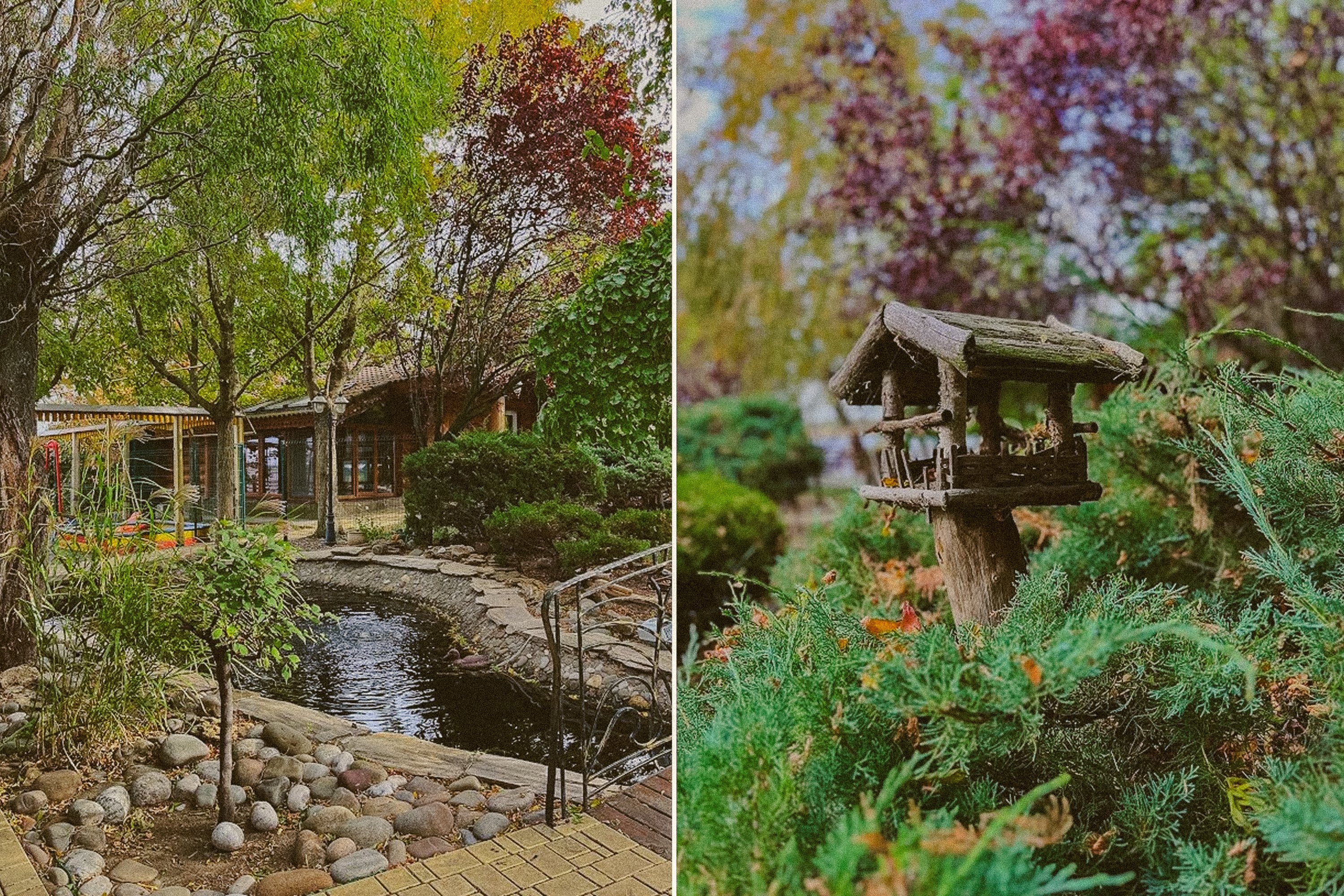

Eugene founded Beykush in 2010, inspired by a family vacation to Europe. After visiting several estates, he became so captivated that he decided to start his own. Upon returning, he set up a boutique operation right at his home near the Black Sea in the Mykolaiv region. For the next few years, he experimented: sourcing grapes, using basic equipment, and gradually mastering the craft.

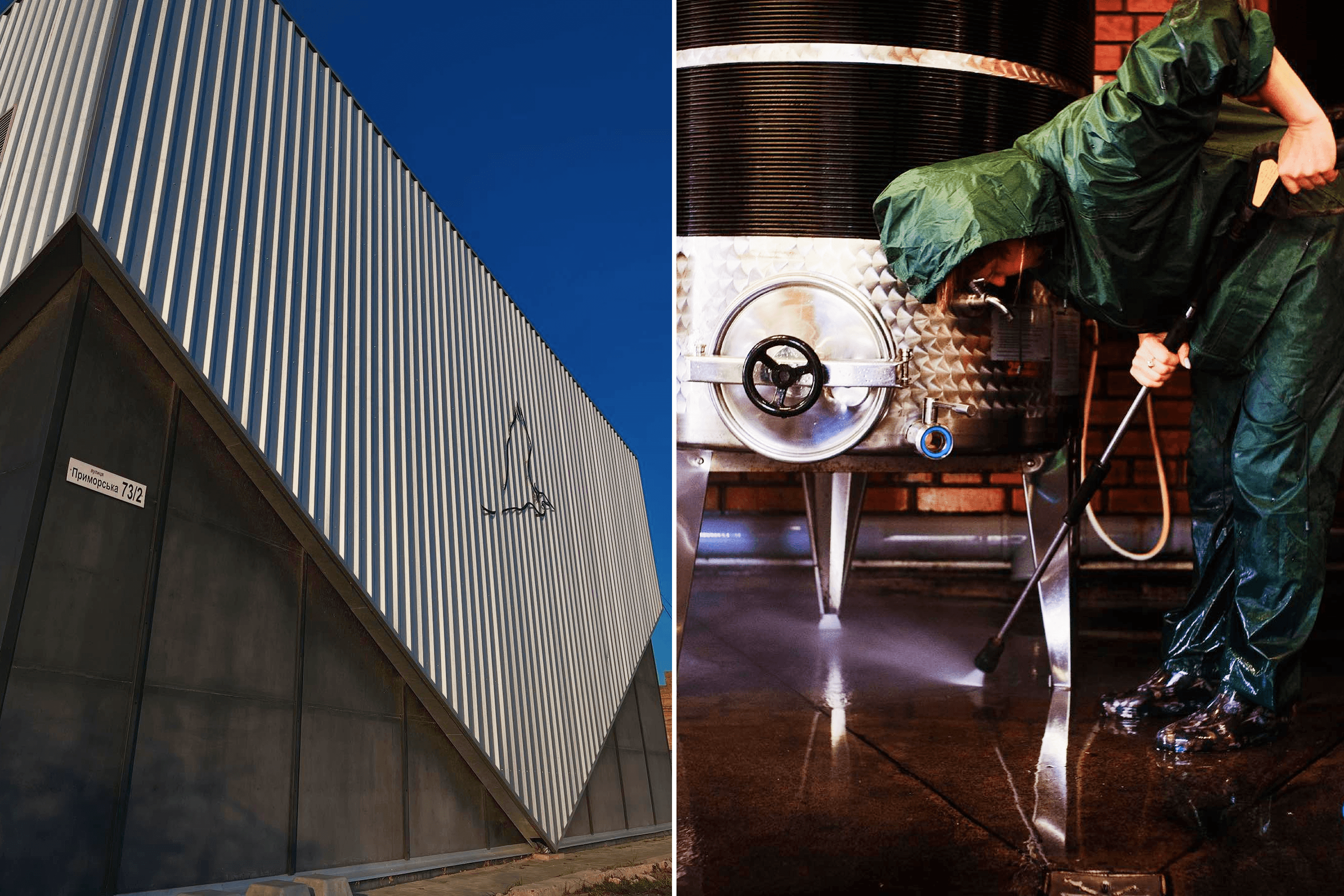

In 2011, we planted our first vineyard—a modest one-hectare plot. By 2020, we had built a full-scale production facility, which allowed us to increase output from 20,000 to 30,000 bottles per year. Our wines were sold across Ukraine in specialized boutiques and select Silpo supermarkets.

Our first foray into export was in 2021. We were approached by a Polish distributor who was already working with Ukrainian craft beer—specifically the Varvar brand. They took an interest in our wine, and we sent two pallets (about 1,000 bottles) to Poland. While it was a one-time collaboration, it sparked the idea of exporting, even though we realized our production volumes were still quite limited.

Just before Russia’s full-scale invasion in Ukraine, Beykush Winery was entering a new level of development. We had launched a new production workshop, equipped a dedicated barrel-aging room, and expanded our vineyards to 11 hectares. Months before 2022, we completed a boutique hotel—five modular houses nestled among the vines—allowing guests to stay longer, enjoy tours, and relax by the sea.

In January 2022, we officially announced the opening; the entire season was booked instantly. Then came February 24. The invasion began.

From the very first days, the Mykolaiv region was under constant threat of occupation and relentless shelling. Three of our employees were mobilized into the Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU). Most of our staff evacuated to safer regions, leaving only two people to look after the winery.

The invasion hit exactly when we were supposed to begin bottling our 2021 vintage. We had a shipment of French glass on its way—we used imported bottles because high-quality domestic production was virtually non-existent at the time. Due to the hostilities, delivering them to the Mykolaiv region became impossible, so we diverted the truck to Transcarpathia, where the bottles sat in storage for months. Meanwhile, the staff who stayed behind worked to preserve the wine in tanks. We also opened our hotel doors to residents from Mykolaiv, offering them free shelter as their city came under heavy bombardment.

In those early days, the sale of alcohol was banned across Ukraine, leaving us with no revenue. Yet, the bills didn’t stop: we had to pay salaries, maintain the equipment, and cover utilities.

A lifeline appeared when Estonian partners reached out to us. By late March 2022, we made our first export to Estonia. Most of the Kyiv Region was already liberated by AFU by then. I remember the drive from Kyiv to Transcarpathia—the air was still biting cold, and the roadside was littered with charred Russian equipment and the lingering smell of smoke. But that shipment was vital; it provided the company with its first bit of much-needed working capital.

It wasn’t until summer that we began shuttling bottles from Transcarpathia to Mykolaiv in small batches. We would bottle the wine on-site and quickly transport it back to safety. Our friend, winemaker Serhiy Stakhovsky, was instrumental during this period, providing warehouse space in Transcarpathia and even personally transporting some of our batches.

In 2022, Beykush achieved a major milestone: our first Gold Medal at the Decanter World Wine Awards for our 2019 Reserve. While we had won silver and bronze before, Gold is a definitive seal of approval for international importers. The organizers also showed immense solidarity by waiving entry fees for Ukrainian wineries from 2023 onward—a significant gesture, considering that submitting ten wines (as we did) would typically cost around £2,000.

We quickly realized that during a full-scale war, export was our only path to survival. The Decanter win couldn’t have been better timed; suddenly, importers were lining up. Following Estonia, we entered the UK market. We had been in talks with a British importer before the war, but the invasion accelerated everything as global interest in “all things Ukrainian” surged.

We knew better than to compete head-on in established markets like France, Spain, or Italy. Instead, we focused on the Baltic states—where there is a deep shared understanding of our context—and the Nordic countries. In the Nordics, where alcohol is heavily taxed, our premium wines can compete with mass-market European labels; they cost the same, but our quality is significantly higher.

In 2023, we met an American importer and subsequently entered the US market. We also began collaborating with Japan; although negotiations with a local distributor had started back in 2021, the first shipments were only made at the end of 2022. Canada became our next priority due to its large Ukrainian diaspora. We have been exporting there since 2024—not to all provinces yet, but we are currently working on expanding our reach. Additionally, I’m in negotiations with two potential importers in Poland: both are interested, so we are in the process of deciding which one specifically to partner with. In 2023, we even exported our wine to Iceland.

In most of these markets, we don’t act alone. We operate under the “Wines of Ukraine” umbrella, an initiative we joined in 2021. There is no internal competition; instead, there is synergy. I saw this firsthand at ProWein 2024 in Düsseldorf: if a buyer asked a Ukrainian producer for a style they didn’t have, they would immediately point them toward a colleague’s booth. As a result, many importers ended up taking multiple Ukrainian brands into their portfolios at once.

Today, roughly 60% of our wine is sold domestically, with 40% going to export. Nearly half of our international sales are concentrated in the UK. As for the other countries, we sell one or two pallets to each one per year. One pallet is around 500 bottles of wine.

In 2023, we launched our own import company in Britain, which now represents eight different Ukrainian producers. It’s staffed by Ukrainian professionals who relocated after the full-scale invasion.

Despite the ongoing war and the fact that the occupied Kinburn Spit lies less than 20 kilometers away, we refuse to stand still. We maintain a steady production of 60,000 bottles annually and continue to plant 1–1.5 hectares of new vineyards each year. Expanding is a significant investment: preparing one hectare costs approximately €20,000, excluding the land itself. This covers everything from sourcing seedlings and soil preparation to installing trellises and modern irrigation systems.

We experiment with grape varieties, planting both internationally recognized and indigenous Ukrainian ones. For example, it’s Telti-Kuruk, an indigenous white grape grown exclusively in the Mykolaiv and Odesa regions, known for its distinct quince-like profile. We were also pioneers in planting the Spanish Albariño in Ukrainian soil, one of the most popular varieties for dry white wine. It was a calculated risk that paid off: the maritime influence and saline sea breezes lend the wine a beautiful minerality—reminiscent of wet stones and a light ocean spray—that would be nearly impossible to replicate in other regions.

The global market has shifted noticeably of late. While in 2022 and 2023, many bought Ukrainian wine out of a desire to support the country, today’s consumers are looking for uniqueness and authenticity. This is why Telti-Kuruk is our international bestseller. You can find a Chardonnay in any corner of the world, but Telti-Kuruk is a discovery you can only make with us.

The era of importers lining up is over; the market has normalized, and we must now proactively hunt for partners. International exhibitions like ProWein remain crucial. For instance, last year in Düsseldorf, we sparked interest from a Malaysian importer. Though the logistics are daunting, negotiations are still moving forward.

The situation at home remains complex. We are striving to return to our 2024 sales volumes, as the second half of 2025 saw a significant downturn. The continuous shelling of major hubs like Odesa and Kharkiv has led to a massive population outflow, shrinking the consumer base in what were once vibrant markets. By early 2026, we began to see a similar trend in Kyiv. These domestic struggles are compounded by a global decline in wine consumption—a trend all producers are currently grappling with.

Given these realities, long-term planning is a challenge. However, our focus remains clear: sustaining and expanding our export footprint. Looking ahead, we have firmly set our sights on re-entering the Polish market in 2026.