Vira Iefremova, 36, has been driven by a passion for science since childhood. Though she initially dreamed of the stars, a high school biology lesson redirected her fascination toward the human brain—a path that eventually led her to a career in neurobiology.

After completing her Master’s in Kyiv and her PhD in Germany, Vira specialized in growing cerebral cortex cells to investigate the roots of brain pathologies. Her journey took her to UC Berkeley, one of the world’s most prestigious universities, before she pivoted from fundamental research to applied science.

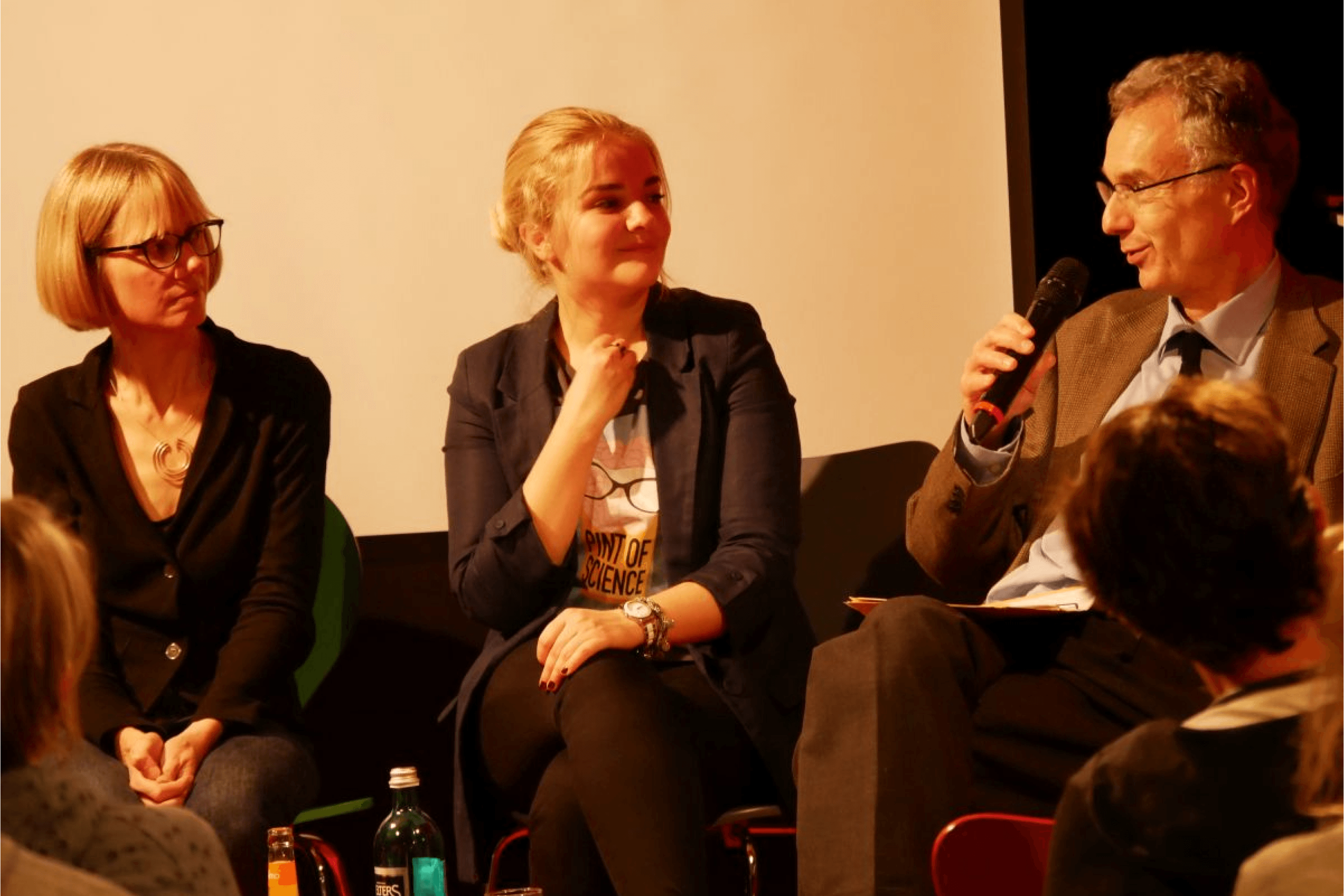

Today, Vira works at the American biotech company Ultragenyx Pharmaceutical, where she develops life-changing medications. Despite her success abroad, her ultimate dream is to return home to advance science and education in Ukraine. Artem Moskalenko, a journalist for the Yellow Blue platform, sat down with Vira to discuss the nuances of global science, her life in the US and Germany, and the fascinating process of growing “mini-brains.”

When did you first become interested in science?

As a child, I was incredibly curious and absolutely loved learning; everything fascinated me. Looking back at the sheer number of questions I peppered my parents with, I actually feel for them now.

When I was ten, my mom told me: “When we look at the stars, we are always looking into our past.” That phrase struck me—it was a total mind-blown moment. From then on, I was hooked on space and astrophysics. But at fifteen, when we started studying the human body in biology, I realized that what truly fascinated me was the architecture of the human brain.

For neurobiologists, the subject and the object of research are one and the same. Essentially, it is the brain itself that allows us to learn how it works. That realization still fascinates me today.

Did you know back in school that you would become a scientist?

I didn’t think of it in those terms back then; I was just really into biology. In high school, I was actually in a humanities track, but I studied the natural sciences independently to prepare for university. In 2007, I enrolled in the Faculty of Biology at Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv. By the time I finished my Master’s, I knew for certain that science was my calling.

How would you rate the quality of biological education in Ukraine?

I definitely felt a lack of hands-on experience and lab work. Some things were simply out of the teachers' hands—for instance, the fact that we didn’t have a €500,000 microscope. But there were other issues that could have been addressed internally. For example, some instructors didn’t have the English proficiency needed to keep up with the latest research and share it with students.

I was lucky, though. I ended up in a department where most professors were fluent in English and even collaborated with international labs. Because of that, our group wasn’t stuck with outdated textbooks or methods. We were constantly tasked with reading current scientific literature—sometimes it felt like a lot, but I’m so grateful for it now. They gave us a rock-solid theoretical foundation, even if the practical side was missing.

What did you do after university?

A friend of mine was studying on a Master’s scholarship in Germany, and I decided to apply as well. At the time, I didn’t know German, but in the scientific world, English is sufficient for professional communication.

The selection process had several stages, culminating in a live interview with German professors who came to Kyiv. It lasted about 45 minutes. Everything was going smoothly until the very end when they asked: “What are your plans after your Master’s?” I replied: “I want to pursue a Doctorate.” That’s what they call PhD studies in Germany. They looked at me and said: “Then go straight for the PhD—why do you need another Master’s?” And they denied my scholarship application.

Initially, I was devastated. But I started looking for PhD openings, applied, and eventually received an offer. So, in 2013, I moved to Germany.

What is unique about the doctoral system in Germany?

It more closely resembles the American PhD model than the Ukrainian one. You don’t simply enroll in a university faculty; instead, you apply for a specific spot within a research project. It’s effectively a job interview. Once you’re in, you are considered a junior research associate rather than just a student.

What was your specialization during your PhD?

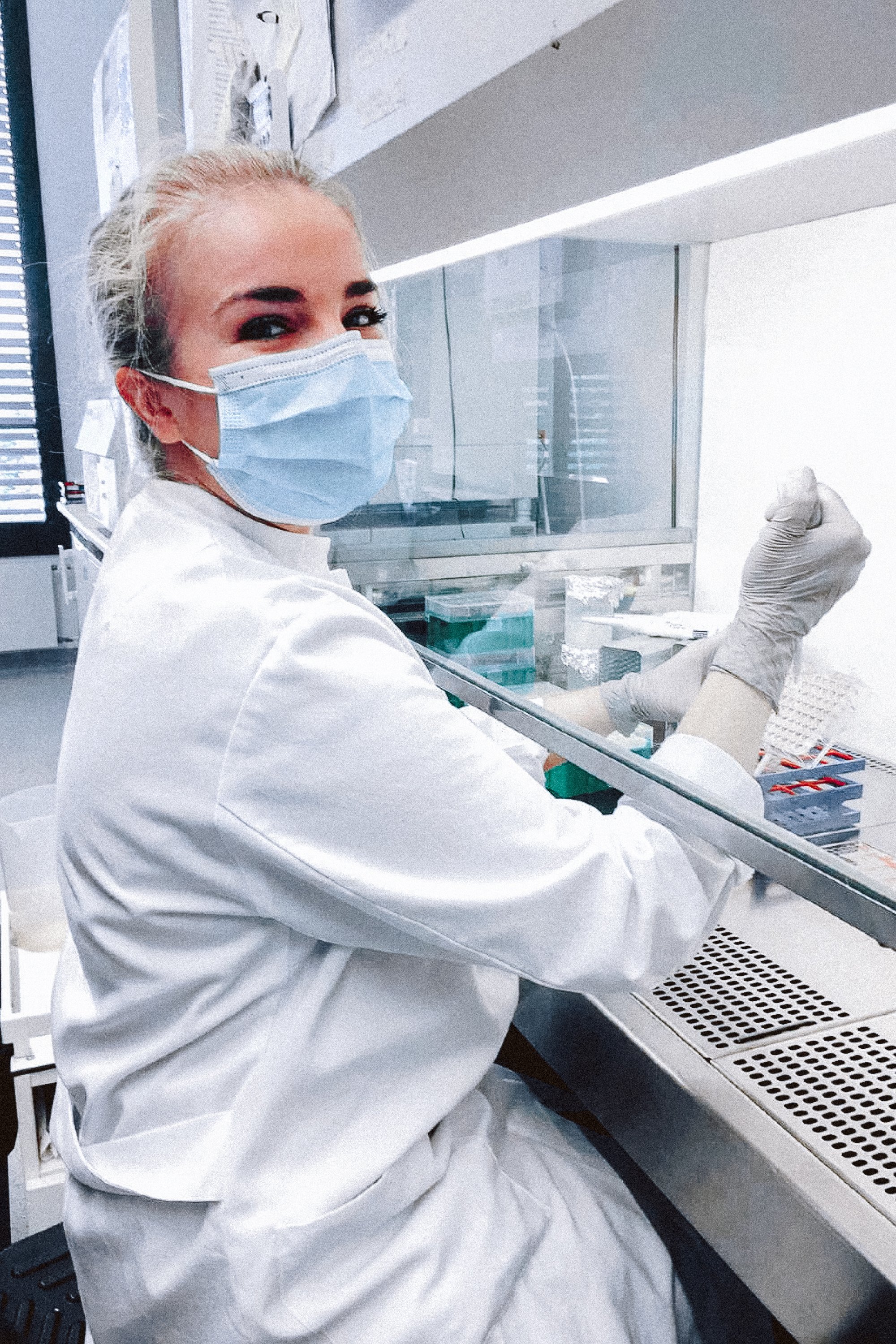

Both then and now, I work with induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). These are human skin or blood cells that are “reprogrammed” in the lab back to an embryonic-like state. From that point, they can be grown into any cell in the body—liver cells, kidney cells, or, in my case, neurons.

I grew cerebral cortex organoids (often called “mini-brains”) to study how genetic errors during fetal development lead to brain pathologies. To do this, I compared cells from healthy individuals with those carrying genetic mutations to see how they grow, interact, and respond to different chemical compounds.

Why did you choose to focus on induced stem cells?

I first learned about them during my Master’s and became obsessed. The method of reprogramming specialized cells into stem cells is a groundbreaking discovery. Shinya Yamanaka discovered it in 2006 and received the Nobel Prize in 2012. I was incredibly inspired by it then, and I’m still in awe today, even after working with them daily for 12 years.

While working on your PhD, did you receive a scholarship or a salary?

I was paid a salary as a research assistant. However, it wasn’t a full rate; I received 50%, which amounted to about €1,500—standard at the time for researchers without a doctoral degree. The system has since changed: Germany passed a law requiring PhD candidates to be paid at least 65% of a full researcher’s salary.

Was that income enough for a comfortable life?

Compared to Ukrainian scholarships and research salaries, I certainly couldn’t complain. But by German standards, it was a modest amount. For instance, student dormitories aren’t as common or accessible there for researchers, so I had to rent a room in a shared flat because I couldn’t afford a private apartment. It was only after I defended my PhD that I could afford my own place and a relatively normal—though far from luxurious—lifestyle.

What was the biggest culture shock in a German lab?

In Ukrainian labs, scientists are forced to be incredibly resourceful; you reuse consumables multiple times and often prepare reagents by hand instead of buying them. In Germany, it’s a different world, especially when working with human cells. Sterility is everything. Hypothetically, if you so much as look at a bottle the wrong way, you discard it. Everything is single-use and strictly regulated to prevent contamination.

And what about daily life in Germany?

Germans have a very specific approach to social life. Few people make new friends in adulthood—they simply don’t see the need to invest the time and emotional energy. The friends they’ve had since school or university are usually enough for them.

This was a real challenge for me, arriving in a new country where I knew no one. Eventually, I did find my circle, and we remain close even though I haven’t lived in Germany for over four years.

After your PhD in Germany, you moved to the U.S. to work at Berkeley. How did that happen?

I was actually just scrolling through my Twitter feed when I saw that a lab at UC Berkeley was looking for someone with my specific skill set. An offer like that is a rarity. Usually, scientists who already have their own research grants approach these top-tier universities to ask for space. But this was a direct job opening for a specific project.

I wrote to the lead scientist, told her about my background, and sent over one of my articles. Then I just closed my laptop and went to bed, not expecting much. To my surprise, she replied and asked for my CV. After four rounds of interviews, I was hired. In 2021, I started at Berkeley, continuing my research on induced stem cells, specifically focusing on the underlying causes of epilepsy.

How would you explain the prestige of Berkeley to someone outside of science?

Berkeley is the Disneyland of the scientific world. It is arguably the best university in the world for natural sciences, with more Nobel laureates on staff than almost anywhere else. In fact, a Nobel laureate worked in the lab right next to mine. She discovered the CRISPR-Cas9 mechanism for gene editing. I use her discovery every single day in my work—it’s incredible to realize that. That level of proximity to world-changing discovery is what makes Berkeley unique.

How much competition was there for the Berkeley position, and why do you think you were chosen?

I’m not sure about the exact numbers for my specific role. However, when I was already at Berkeley and we posted openings for similar positions, we would get 200 to 300 applications within the first 24 hours. These are top-tier scientists with PhDs and publications in prestigious journals. Since everyone’s technical skills are roughly on par, the deciding factor often comes down to “cultural fit"—personality, character, and whether the person will mesh with the lab team.

This isn’t just an American thing; it’s the same in Germany. Your qualifications might be perfect on paper, but if your future colleagues walk out of the interview saying, “Goodness, no, I could never work with her,” you won’t get the job.

How did the work culture at Berkeley differ from Germany?

At Berkeley, everything is much more egalitarian; hierarchy is almost non-existent. At my first meeting, a Nobel laureate just walked up to me and said: “Hi! I’m Jane, and you?” Not Dr. Jennifer, Nobel Laureate—just Jane. At Berkeley, people don’t lead with their titles; if you don’t already know someone’s status, they aren’t going to tell you.

Germany is different; it has a very traditional, vertical hierarchy. It’s even baked into the language. In German, like in Ukrainian, there is a formal “You” and an informal “you”. There are rigid formalities you must observe when speaking with a professor. Only they can suggest moving to the informal “you.” If they don’t, you could work together for years and never drop the formal address.

That said, colleagues from other American universities told me Berkeley is a bit of an outlier. Most U.S. institutions are more formal—closer to the German model than to Berkeley’s relaxed atmosphere.

Is hierarchy the only major difference?

There’s also the level of freedom. In the U.S., it’s incredibly high—freedom in your experiments, your thinking, and how you organize your day. It’s generally not about what time you clocked in, but the quality of your results. In Germany, this is impossible: if the workday starts at 9:00, that applies to everyone.

This freedom extends to intellectual approach: how they formulate hypotheses and tackle experiments in the U.S. is much less bureaucratized. There’s far less of that rigid logic of “this is the way it’s written, so this is the only way it can be done.”

In that sense, is Ukrainian science closer to the American or German model?

It’s somewhere in the middle. It’s not as regulated as in Germany, but not as free as in the U.S. I think this is due to a generational shift. Younger Ukrainian scientists are looking at global standards, taking international courses, and engaging with the global community.

At the same time, we still have many outdated rules—often a Soviet legacy. But because these rules don’t operate as systematically as they do in Germany, they are actually easier to break. This allows us to start from scratch and build something new, cherry-picking the best practices from different countries.

Did you face any discrimination abroad for being a foreigner?

I didn’t feel it in the scientific community in Germany. However, I had a few unpleasant encounters with state institutions—specifically immigration services. There was a noticeable patronizing tone, and stereotypes about Eastern European women would often surface. I was literally asked if I had come to Germany just to find a husband. Even a mountain of documents proving my scientific work didn’t stop those questions. I also encountered some sexism in German science, though it’s much less pronounced than in Ukraine.

In California, it’s a completely different story. People here come from all over the world; your background usually sparks curiosity rather than prejudice. Perhaps in more conservative parts of the U.S., the experience would be different.

Did the attitude toward you change after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine began?

I saw a wide spectrum of reactions. Initially, some sincerely believed the “Kyiv in three days” narrative. Others simply refused to process what was happening. There were even people who didn’t know where Ukraine was on a map.

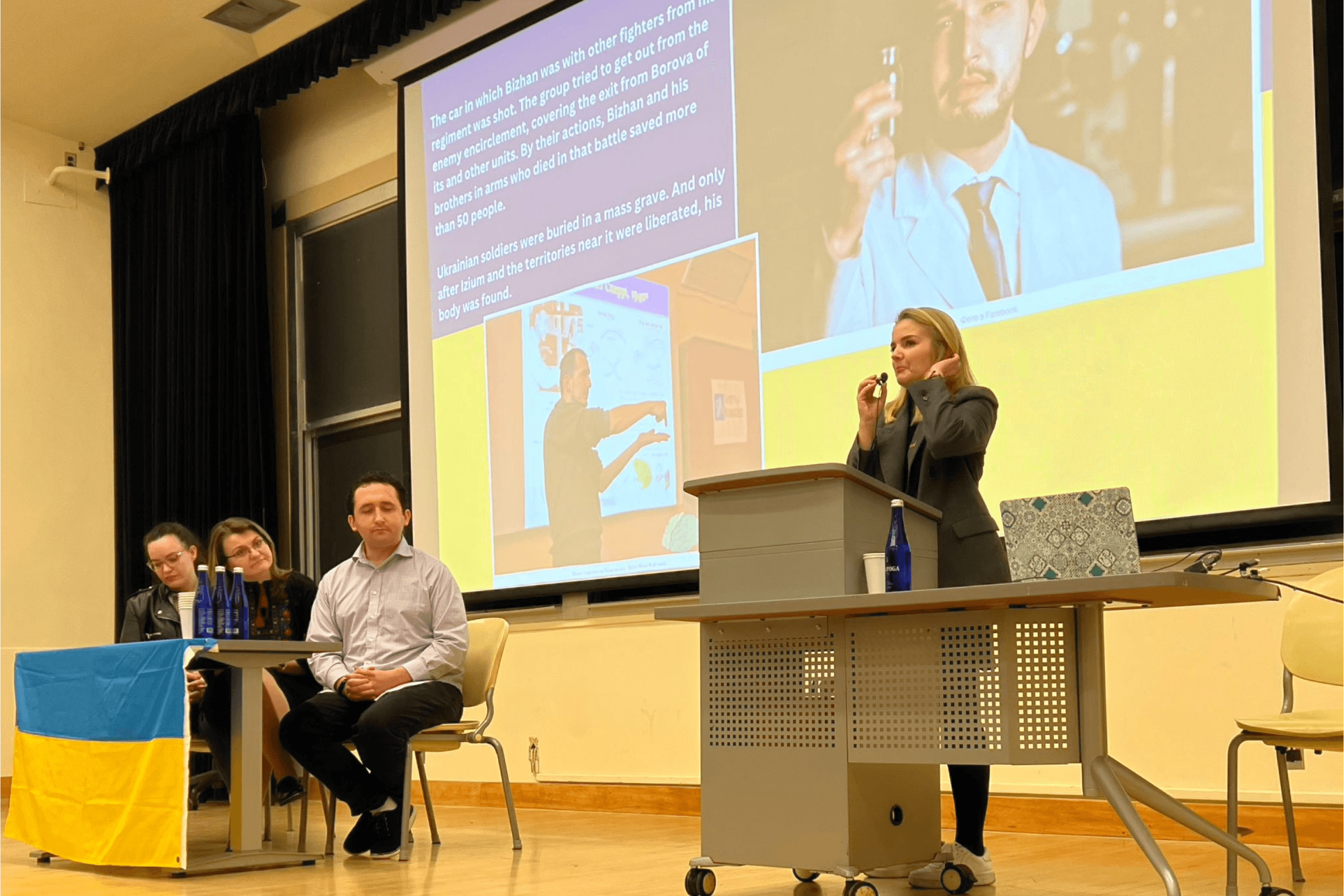

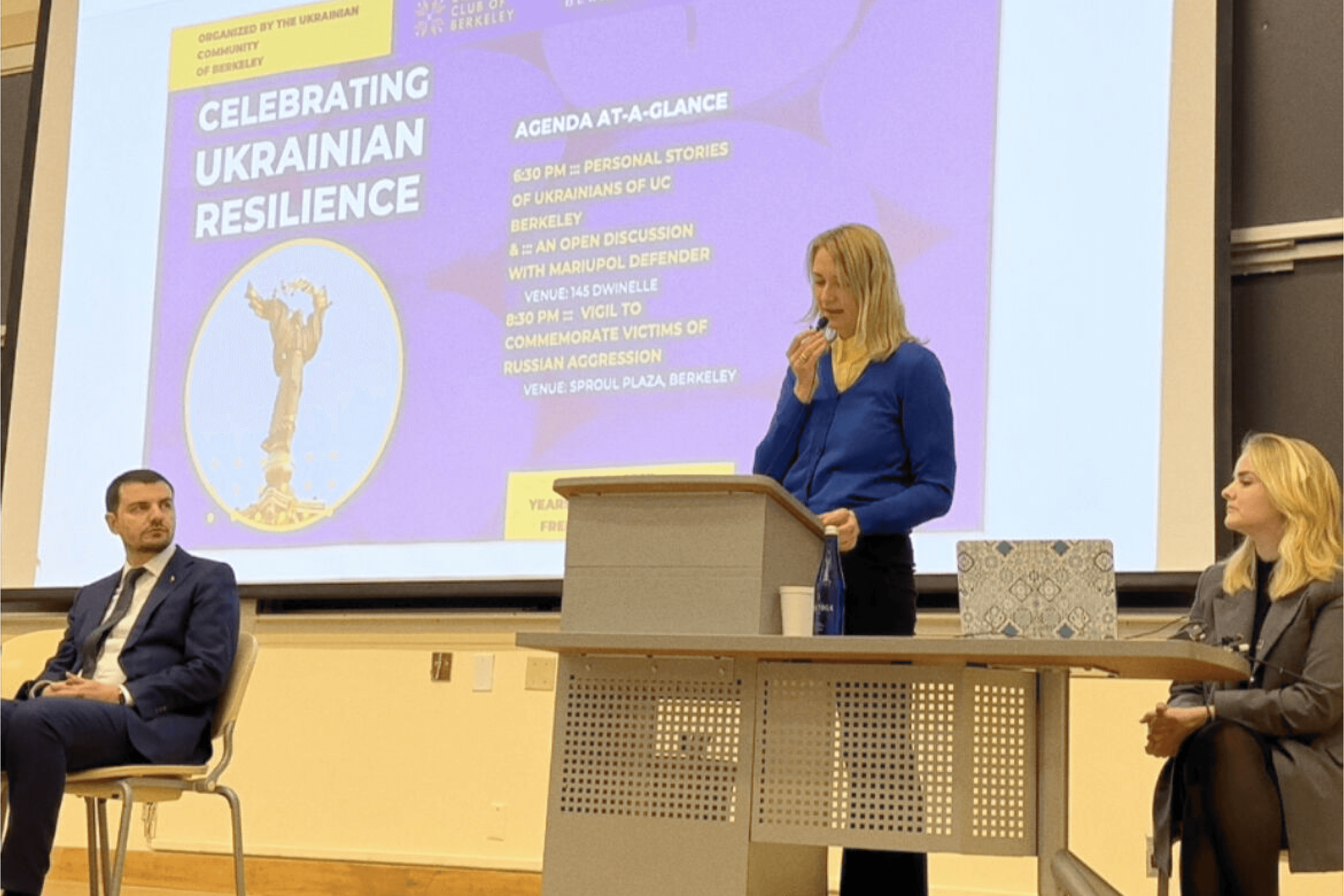

I wouldn’t say I noticed a significant shift in how people treat me. Everyone knew I was unapologetically pro-Ukrainian, and it never caused any friction. I attend protests, and together with two fellow Ukrainian scientists, I co-founded a non-profit to raise funds for rebuilding schools destroyed by the war. People have been generally supportive.

I’m frequently asked about the situation back home because, unfortunately, Ukraine is no longer a headline fixture, and many Americans assume the war is over. I always tell them: “Believe me, when it ends, you’ll definitely hear about it.” Often, the conversation shifts to a deeper historical and cultural context. Russian propaganda is pervasive in both Europe and the U.S., so many foreigners still lean on the “great Russian culture” trope, citing Dostoevsky and the ballet. That’s when I have to educate them about the GULAG, genocides, and mass deportations.

How does a scientist’s salary in the U.S. compare to one in Germany?

There’s a common misconception that working at Berkeley means you’re wealthy. That couldn’t be further from the truth. California is incredibly expensive, and Berkeley sits in the heart of the San Francisco Bay Area—right next to Silicon Valley and the headquarters of Google, Meta, and Apple. If you work in academia here, you are technically living on the edge of poverty by local standards. That is no exaggeration.

In Germany, after defending your dissertation, you might earn around €3,000; in California, it’s about $4,000. For this region, that is a pittance. A waiter in a high-end restaurant can easily earn 50% more than a scientist at Berkeley.

How do scientists manage to survive there?

In the U.S., it’s quite common to straddle the line between academia and the startup world. At Berkeley, nearly every second person is either working for a startup or launching their own. Europe is the opposite: in Germany, for example, you are usually either in academia or in the industry. The system is designed such that moonlighting in both is practically impossible.

How does research funding work in the U.S.?

It’s almost entirely grant-based, relying on the state or private foundations. Even lab heads who are Nobel laureates have to regularly write grant applications. A Nobel Prize adds immense prestige to your name, but it doesn’t grant you “automatic” funding. This is just the way the system works.

Essentially, a grant application is your business plan. You have to convince a foundation or the government that your vision is sharper and more viable than 100 other applicants. Science is an incredibly competitive arena.

Is this competition strictly about the money?

Not at all. The competition happens on two fronts. The first is purely scientific: someone else, somewhere in the world, is almost certainly working on the exact same problem as you. It’s a race to publish. If you discover a breakthrough—say, a new mechanism for treating a specific cancer—but someone else publishes it a day before you, your results lose their impact.

This intense pressure often means working grueling 14- to 16-hour days. In science, you are in a perpetual race—not just for speed, but for data quality, experimental precision, and the sheer depth of your analysis.

Then there’s the struggle for funding, which creates a vicious cycle. To secure your next grant, you must prove that you’ve used your previous funding effectively and demonstrated tangible progress. This doesn’t always mean achieving “positive” results; in fact, proving that there is no correlation between X and Y or debunking your own hypothesis is valuable science. The key is to show that your conclusions are evidence-based and contribute meaningfully to the field’s understanding of a problem.

You left Berkeley in 2023. What prompted that move, and where are you now?

I spent about two and a half years at Berkeley and truly loved my work. However, I eventually felt a pull toward applied science. I wanted to take my research on epilepsy and see it translated into real-world practice—specifically through the development of new drugs or therapeutic interventions.

In 2023, I joined a startup that leveraged artificial intelligence to develop treatments for neurodegenerative diseases. I spent over a year there, continuing my work with induced stem cells.

However, as the political climate shifted and it became clear that Donald Trump would return to the presidency, the investment landscape changed drastically. Investors who had previously injected millions into biotech startups like ours began to pull back. There was a general understanding of the new administration’s stance toward science and medicine. Given that medical R&D is a long-term game, the surrounding instability made these high-risk investments less attractive.

I began looking for a new challenge, and since March, I have been with Ultragenyx Pharmaceutical. The company focuses on developing treatments for rare and ultra-rare diseases. This is familiar territory for me, as I worked on rare pathologies during my PhD and at Berkeley.

My current role involves growing disease-modeled cerebral cortex cells to test their reaction to various chemical compounds. These are the lead compounds our company is developing; by observing the cellular response, we can identify which ones have the potential to actually treat the pathology in patients.

If you compare the private sector to academia, is there more freedom or more constraint?

I’ve been fortunate to find a company that fosters autonomy. Here, I have the opportunity not only to execute assigned projects but also to pitch my own ideas. That’s a rarity in the corporate world, where the standard approach is often: “Here is the project, here is the disease—get to work.”

A colleague of mine at this company proposed a drug for a rare central nervous system disorder eight years ago. His proposal went before the Scientific Advisory Board; they confirmed the science was sound and that there was a significant patient need, so they greenlit a pilot project. Typically, these pilots run from several months to half a year. If the results are promising, the project receives full backing.

That specific project is now in its final stages of development, moving toward preclinical trials on primates. If all goes well, we could see human clinical trials within a year.

How has the policy of the current administration under Donald Trump affected your work?

Personally, my work hasn’t been directly impacted because I’m in a commercial biotech firm that doesn’t rely on federal grants. But for my peers in fundamental science, the consequences have been devastating: budget cuts, the shuttering of research groups, and entire labs being forced to close.

The most tragic development has been the overnight termination of over 20 clinical trial programs for mRNA-based cancer vaccines. Simply because that technology became a political flashpoint during the pandemic, programs that were the final hope for many patients were axed. People were essentially told: “We no longer have the legal authority to treat you.”

Beyond the lab, we’re seeing a dismantling of the education and healthcare sectors. The 50% staff reduction at the U.S. Department of Education is a massive blow to a system that already had deep cracks. California manages to buffer some of this with its own resources, but Republican-leaning states are losing funding for everything from school lunches to inclusive education. As a scientist, what scares me most is that this creates a generation of voters who are more susceptible to populism than to complex, evidence-based solutions.

Are you facing difficulties staying in the U.S. during this second Trump term?

My immigration status has always been tied to my scientific work. I don’t have U.S. citizenship, nor do I plan to seek it. However, I have a Green Card, which I received at the end of last year. It provides a vital sense of stability. I realize I was incredibly lucky; I secured my permanent residency about a month before the inauguration. If I were starting that process today, I suspect it would be an uphill battle.

Have you considered migrating elsewhere—to Canada, for instance—as many of your colleagues have?

I think about it every day. But it’s less about moving to a third country and more about returning to Ukraine. I’m currently trying to identify exactly where I can be most effective. It wouldn’t necessarily have to be in a lab; I’m deeply interested in educational and scientific reform. I now have a wealth of experience across different global systems that I want to bring home.

Returning isn’t a snap decision—I have projects, a team, and professional commitments here. But I don’t see my long-term future in the U.S. To be honest, if the political climate had been like this when I was first considering the move, I probably wouldn’t have come here at all.

My current plan is to either return directly to Ukraine or move back to Europe as a stepping stone. It all depends on finding work that is intellectually fulfilling and allows me to live a sustainable life.