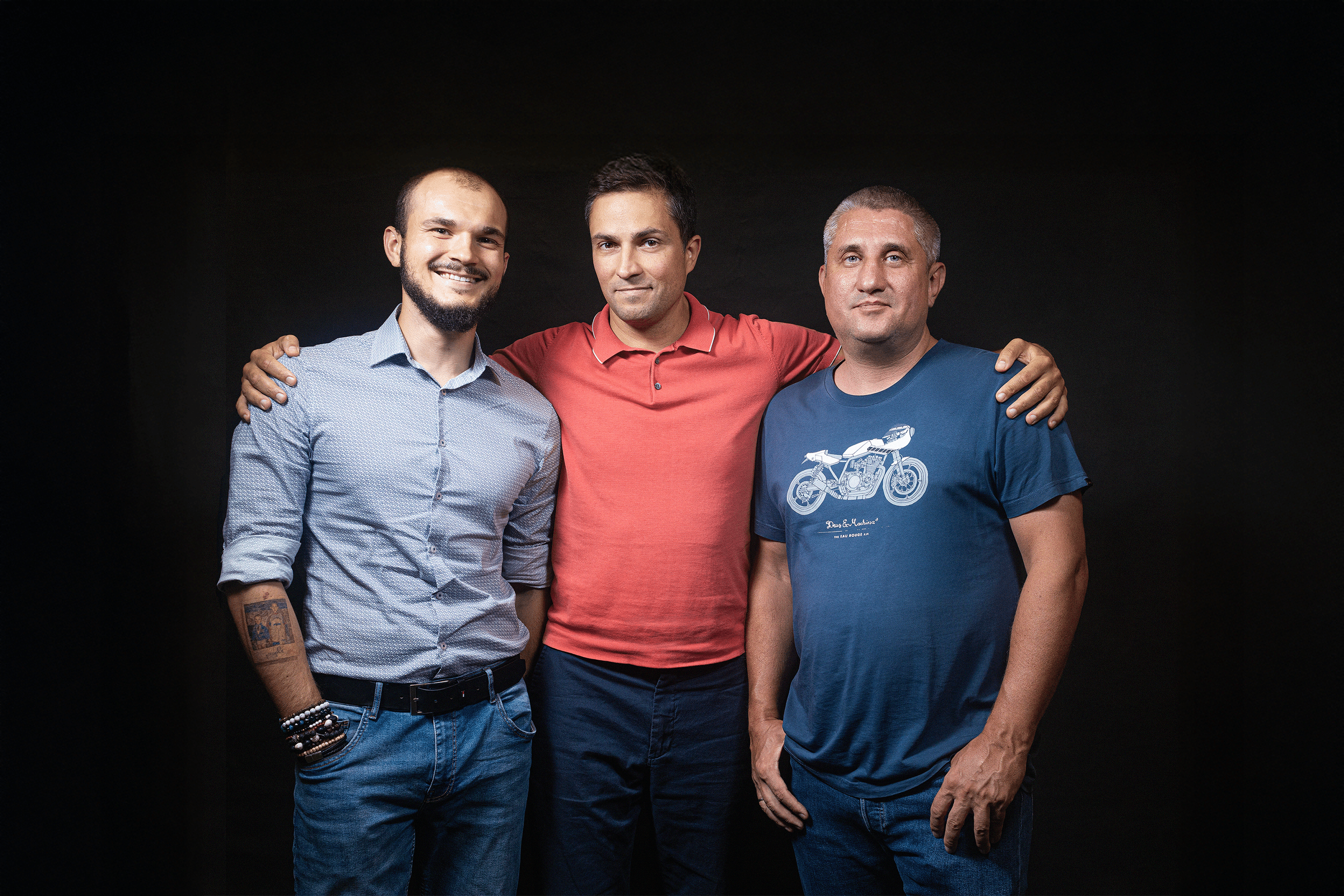

Artem Chyhyrynskyi is the co-founder and CEO of Advin Global, a company that primarily creates marketing and training projects using VR or AR for other businesses. Artem studied economics and management at Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv and later worked on various IT projects. In 2017, he and two partners founded Advin Global to explore virtual or augmented reality, technologies that were almost unheard of in Ukraine at the time. The team started with just three people; now, it has over three dozen. Advin Global’s portfolio includes more than 250 successful projects for Ukrainian and international brands.

In 2022, following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the company began developing its own products. The first was VRNOW, a simulator for the rehabilitation of patients with amputations and other musculoskeletal conditions. Using virtual reality, it alleviates phantom pain and accelerates adaptation to a “new” body.

The simulator is already in use at more than 10 Ukrainian hospitals, and Advin Global plans to enter the Polish, Italian, and German markets soon. Next up are more European countries, the United States, and Asia.

YBBP platform journalist Artem Moskalenko met with Advin Global CEO Artem Chyhyrynskyi to ask about the technology’s principles, the prospects of the health tech market in Ukraine, and the export potential of the VRNOW simulator.

Tell us a bit about Advin Global. How and when did you found the company? What did it do before developing its own products?

My partners and I founded Advin Global in 2017. Back then, augmented and virtual reality technologies had minimal penetration in Ukraine, but there was a demand for them—particularly from marketing companies and brands. So, we decided it was a good field of opportunity for development.

Initially, we created projects for other companies—Visa, PrivatBank, McDonald’s, DeLonghi, Tefal, Coca-Cola, and others. They were mostly marketing-related, but we also had programs for training employees in manufacturing.

Since 2017, we have implemented over 250 projects, and our clients have included not only private companies, but also state organizations. For example, last year, we collaborated with the Office of the President of Ukraine to develop a communicative VR campaign for the Peace Summit in Switzerland. We created a 3.5-minute, 360-degree video for the delegates. They put on VR headsets and saw a little girl from Irpin showing them her destroyed home, kindergarten, and playground.

Another project is “Kyiv region. Places of memory.” In Borodyanka, Irpin, Bucha, and on the Romanivskyi Bridge, we installed augmented reality mirrors that transport people back to 2022, showing all the horrific events that occurred during the Russian occupation of the Kyiv region.

After the full-scale invasion began, we continued to do custom projects but also started developing our own products based on VR and AR. The first was VRNOW—a simulator for the rehabilitation of patients with amputations and musculoskeletal limitations.

Why did you decide to create your own product specifically in the medical field?

Since 2022, there has been an acute and urgent need for products that can help rehabilitate people who have lost limbs. The longer the full-scale war continues, the more such people there are: by the end of 2024, there were, by various estimates, between 60,000 and 120,000 persons with amputations in Ukraine. Most of them are a result of the war.

Over 85% of these patients experience phantom pain—it’s severe, and there’s almost no relief from it. One of the main treatment methods that exists in the world today is mirror therapy. It has been used for decades, but as the experience of doctors and patients shows, this method is outdated and largely ineffective.

That’s why we decided to create VRNOW. Thanks to a special mode, it helps patients with amputated limbs combat phantom pain. But it can also be used to treat other musculoskeletal limitations—for example, after strokes or mine-explosive injuries.

What is the unique aspect of your technology and the special mode you mentioned?

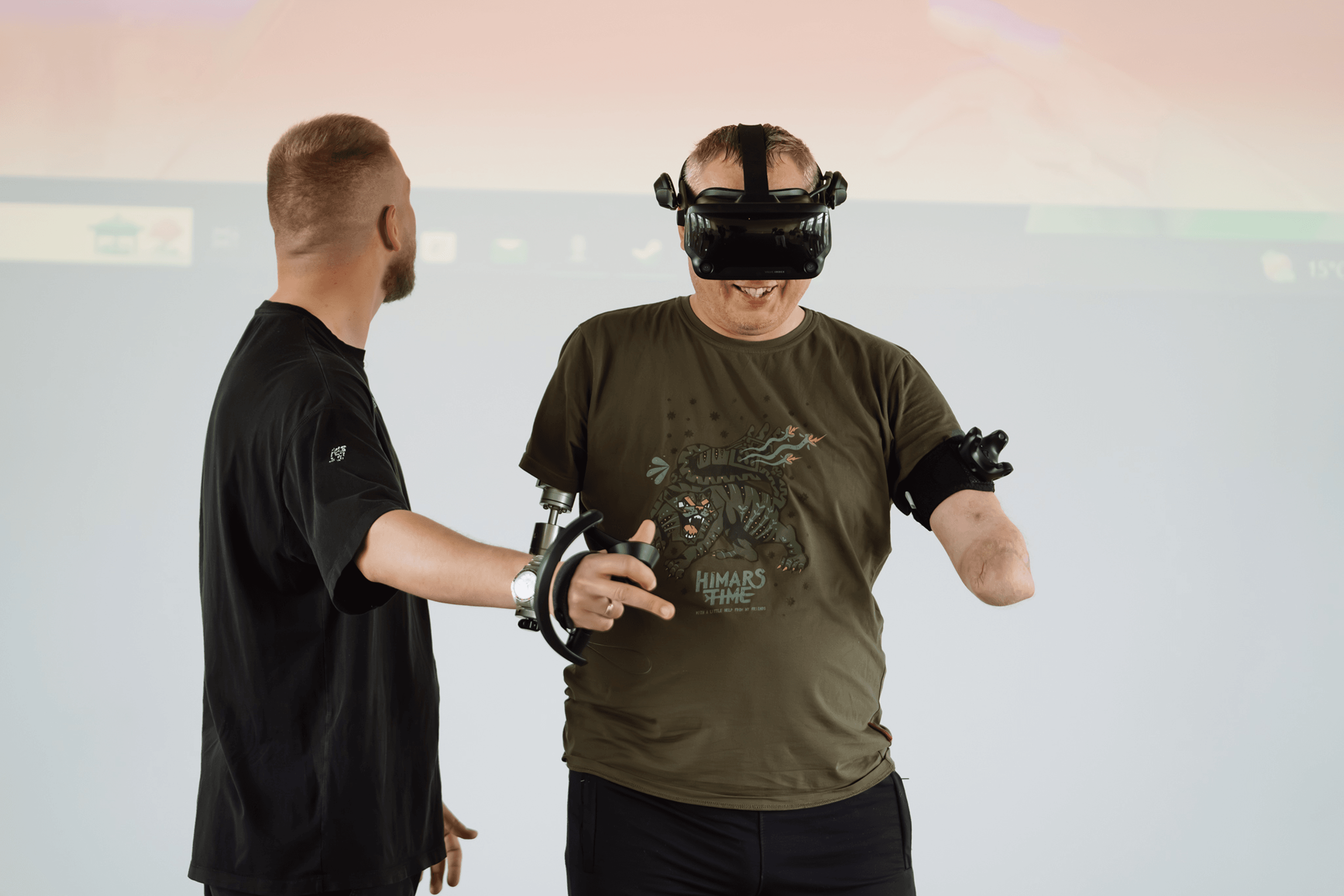

The patient puts on VR goggles, and special trackers—up to five of them—are attached to their body. Two sensor panels are also installed in the room, which outline the place’s boundaries in virtual reality.

Then, in the VR environment, the system creates a complete digital copy of the body, considering height and weight—essentially a 3D avatar that accurately mirrors movements. The only difference is that in virtual reality, the limb is not amputated; the person sees themselves with a whole arm or leg and feels this virtual body as their own. This mode is called “Virtual Limb” in our system, and it is the key element in phantom pain therapy.

In virtual reality, the patient can play soccer with legs they don’t have or pick up objects with their hand. The program has four environments: two rooms, a kitchen, and a sports gym. We have also developed over 50 exercises for training muscles, mobility, and coordination.

The main difference between our technology and mirror therapy is active interaction. The patient doesn’t just observe; they are immersed in the process, moving their amputated limb. Some patients said they felt their arms and legs almost as they did before the amputation. This is the essence of the immersive technology: it allows for complete immersion in the environment, thereby reducing the level of phantom pain.

So, virtual reality tricks the brain better than a mirror?

Yes, absolutely.

Is the effectiveness of VR in treating phantom pain your hypothesis that you’ve tested, or is it already a globally established fact?

A number of studies and pilot projects conducted in the US confirmed that virtual reality can help overcome phantom pain. We built on this groundwork and assembled our own team of over 30 highly qualified specialists—3D modelers, engineers, VR developers, artists who created the virtual space, and managers. We also involved scientists and doctors who helped with the exercises and methodologies.

There are only a few products in the world that accurately replicate body movements through a 3D avatar. They belong to multi-billion dollar companies that create games like Half-Life. Our product combines human body kinematics in VR with unique medical scenarios and environments. This is precisely what makes it one of a kind.

We began testing the simulator at the end of 2022. Since then, over a thousand patients have undergone therapy on it. The results show a stable reduction in phantom pain.

Who did you collaborate with during VRNOW’s testing?

We worked and continue to work with the Path to Health clinic in Dnipro. It’s a rehabilitation center with a large patient base and highly qualified specialists: physical therapists and specialists in physical and rehabilitation medicine. They are constantly searching for new solutions and approaches to rehabilitation, so we quickly found common ground. We also tested some technological hypotheses at the Adonis clinic in Kyiv—and they still use VRNOW for patient rehabilitation there.

Some of the doctors we work with even present case studies on using VRNOW in their practice at the conferences.

In what percentage of patients does the level of phantom pain actually decrease after sessions on your simulator? How many sessions are needed, and how do you measure this?

We don’t have precise statistics yet, because it’s not possible to collect data on all patients or from all hospitals. But from what we do know: almost 100% of those who completed the therapy and whom we were able to survey report significant pain relief.

Typically, patients undergo a course of 15–25 sessions over a period of one to three months. One session lasts an average of 45–60 minutes, depending on the doctor’s decision. Before and after the course, the pain level is measured on a ten-point scale. For example, at the beginning, a patient might rate the pain at 8–10, and after the course, it’s down to 1–3.

Military personnel and civilians, adults and children have all undergone rehabilitation on our simulator. Positive dynamics were observed in people post-stroke and in those with mild forms of cerebral palsy. Of course, there are patients who find it difficult to adapt to virtual reality—for instance, due to vestibular disorders. There are also contraindications, such as for concussions.

How many hospitals in Ukraine are currently using VRNOW?

Currently, more than 10—both public and private. Besides the ones I mentioned earlier, this includes Okhmatdyt and the Nikopol Regional Children’s Hospital, as well as several military hospitals. VRNOW will soon be installed in the Unbroken center in Lviv.

We have also signed contracts with our distributor to install 25 simulators in hospitals in Kyiv, Odesa, Lviv, and Dnipro. They are on the list of over 110 hospitals that the Ukrainian Ministry of Health has designated as base facilities for the rehabilitation of people after amputations.

How much does one simulator cost, and what is included in the price?

The installation of the simulator itself, staff training lasting 1–2 days, regular system updates, and 24/7 technical support cost UAH 1.8 million.

We have a rule: for every 5 simulators purchased, we install one for free—in a hospital or medical facility that cannot afford to buy it. The demand for charitable installation of the simulator is very high. We currently have over 40 official requests from hospitals across Ukraine. We carefully select where to send the simulator—we hold an internal discussion, something like a small tender. We look at the number of patients undergoing rehabilitation at the hospital and how great the need is. We also consider the hospital’s location and the staff’s willingness to learn.

In essence, you created unique software for your simulator. Did you protect it legally?

Yes, we understood from the beginning that we would patent it, as our main asset isn’t machinery or equipment, but the technologies and software products we create.

VRNOW became the first technology in Ukraine’s history to be patented as a high-tech medical device. It was a difficult and lengthy process.

How long did it take, and what difficulties did you face?

It took over a year from filing the application to receiving the patent; usually, the procedure is a few months shorter. First, we prepared a large package of documents: technical descriptions, drawings, test results, confirmation of functionality, software data, and so on. Then we submitted the application to the Ukrainian National Office for Intellectual Property and Innovation. It conducts an expert review, checks for uniqueness, technical novelty, and the absence of global analogs.

You created the software, but where do you get the hardware—the VR goggles, the sensors?

We have several suppliers; the main one is Valve. We buy VR goggles from them. There are a few other international suppliers for sensor systems, trackers, and other computer hardware. However, there are also elements we develop ourselves—for example, the mounts and body pads to ensure the sensors sit correctly on the patients and don’t interfere during sessions. We even designed the ceiling mounts for the wires.

All these components, together with our software, make up the complete rehabilitation product—VRNOW.

How much did the simulator’s development cost, and how long did the process take?

We invested over $400,000 in VRNOW. The development took almost 2 years—from late 2022 to late 2024, when the simulator was first installed in a medical facility for practical use.

But we are still improving VRNOW—adding new functions, taking feedback from patients, doctors, and partner clinics into account. We release at least 2–3 updates per year, which allows the system to remain technologically up to date.

Right now, you are only selling VRNOW on the domestic market in Ukraine. Do you plan to expand to foreign markets?

Yes, we are planning to export. We started thinking seriously about this late last year when we were invited to present the simulator at the World Economic Forum in Davos. There, we received the Global Impact Award, given for projects that have a significant impact.

After that, the international audience began to pay attention to our product. Europe, America, and even Asia understand that the Ukrainian experience is extremely valuable because a large number of patients with different types of injuries are concentrated here. People started approaching us more at various events, asking for contacts or collaboration terms. The number of emails also increased. We began to receive invitations to other international events. One of the latest was the Ukraine Recovery Conference in Rome.

We realized it was time to work on exports. We conducted research and identified the first three countries where we want to sell the simulator—Poland, Italy, and Germany. We chose them because they have the highest concentration of rehabilitation centers and, consequently, a higher demand for equipment.

What is needed to enter these markets?

Three months ago, we filed for patents in 9 European countries. These are the 3 countries I mentioned plus 6 more we want to enter later. Each of them, despite all being in the EU, has its own patent legislation. We expect to have all the patents by the year end.

Next will be the certification stage. Unlike patents, certification is unified across all the European Union. So, we only need to pass it once, and we’ll be able to officially supply the technology to all EU countries. In parallel, we are already working on signing contracts with local distributors in Poland, Italy, and Germany.

For objective reasons, Ukraine has significantly more people with amputations than the EU. Who will your customers be in Europe?

We work with all forms of musculoskeletal disorders, so there is demand in Europe—even as there are fewer people with amputations. Moreover, new rehabilitation centers for people with various types of injuries or diseases are actively being built there; in Germany and Italy alone, there are already more such centers than in Ukraine. And they need high-quality technological solutions.

Our simulator can be integrated not only into medical but also into wellness complexes, as well as into sports rehabilitation programs. The potential field of use is quite broad. We see the demand and understand that it will only grow.

How much will the simulator cost in the EU?

The estimated price will be €43,000. The model is the same as in Ukraine: the simulator, training, updates, and technical support.

You mentioned you are already working with local distributors in three countries. Where did you find them?

International exhibitions or events like the Davos Forum or the Recovery Conference help in this regard. These are places with a high concentration of people interested in innovative technologies. A point where the interests of business, science, and capital converge. You can find potential partners there.

We have also signed contracts with consulting companies that are helping us enter local markets and find distributors. For example, we already have such an agreement in Italy. We are scheduled to meet with several potential distributors very soon, and after that, we’ll decide exactly whom we will work with in the Italian market.

Does the award you received at the Davos forum help in making contacts?

It definitely played a role in our brand’s image. But if we talk about practical impact—for instance, someone saw the award and decided to sign a contract or order a simulator—that hasn’t happened. It’s more about prestige and reputation than about direct sales or partnerships.

How much will it cost you to enter the EU market?

I think up to $500,000. But this will be a proper entry into the international market—systematic, and with a good “concrete foundation.” You could just sell one simulator from Ukraine to someone in Poland or Italy—even without certification, if it’s a private center—and say, “Okay, we’ve entered the EU market.” We are not interested in that path.

We want to build a truly strong, sustainable business. This requires investment in marketing. In the medical field, presence at specialized international exhibitions is important—at least at 10–15 per year. Participation in each costs about $10,000. So, that alone will take $100,000–$150,000.

Next, there must be a team—those who will work in warehouses, assemble and install the simulators, and train specialists. And I’m not even mentioning the bureaucratic procedures, participation in tenders, and so on. We also need to hire at least one manager in each country who will work with the local distributor.

Are you planning to raise additional investment to start exporting?

We are currently in the process of seeking financing. There is an offer from potential investors regarding the sale of a stake in the company—about 10%. But this is still at the negotiation stage.

If we had the necessary amount of money, we would enter the market of 9 EU countries much faster. As it is, we have to act in stages. Relatively speaking, if we manage to attract an investor and sell a stake, we will complete the entire pool of work within a year, perhaps even faster. If there is no additional money, the process will take 2–2.5 or even 3 years. We will do it either way; it’s just a matter of time frames.

Do you only want to be present in the European market?

In the long term, we are thinking about entering the US and Central Asian markets. Perhaps next year we will participate in a major medical exhibition in Dubai—WHX Dubai. It’s one of the largest medical events in the world, bringing together distributors, investors, and hospital representatives. For us, it’s an excellent opportunity to make a statement and establish contacts. We aim to be there within the next 5 years, but for now, the main focus is the EU.

How do you assess the prospects of the health-tech market in Ukraine as a whole?

In Ukraine, it is just forming. Over 95%, and possibly even 99% of high-tech medical equipment is still imported from abroad—and this makes it more expensive and less accessible.

Given this and the unprecedented number of patients with various types of injuries and rehabilitation needs, now is a unique moment for the development of Ukrainian companies in the medical technology sphere. This doesn’t just apply to physical rehabilitation. There is a demand for projects in mental health, innovations in ophthalmology, neurorehabilitation, and other areas.

The state promotes the development of the defense industry—in particular, it created the Brave1 platform. Are there similar solutions for the development of medical innovations?

We managed to receive a €50,000 grant through the Seed of Bravery program. Of course, this is support for our company, but obviously, it cannot be compared with what the state is doing for the defense industry. A Brave1 for the medical sphere does not exist at the moment.

How could the state help you, besides grant support?

We would like to deepen interaction directly on the ground—with hospitals. What I mean is that medical staff in the field are not always ready to accept new technologies, and this needs to change.

I see potential in cluster solutions that unite doctors, technology companies, and local medical institutions. This could be the next step for the development of our industry.

I believe that Ukraine has great potential to become a European-level R&D center in the health-tech sphere. There is rapid communication with hospitals and patients here, and less bureaucracy than in Europe. All this allows for the rapid testing and implementation of innovations.

If strong research and development hubs are developed, Ukraine could transform into the European capital of medical innovation—similar to what has already happened with defense tech, where Ukrainian companies are demonstrating a world-class level.

How do you see the future of your own company?

We are already expanding the directions of our development. We are currently working on an ophthalmological product for children under 12, which helps correct strabismus (crossed eyes) and other vision problems. We have already found experienced ophthalmologists who are helping us. The product is planned for release in 2026-2027.

We are also developing a rehabilitation simulator of a different configuration, without the Virtual Limb mode. It will not treat phantom pain but will be more focused on physical exercises, with an expanded number of game mechanics.

In the mental health sphere, we have ideas for combating PTSD. The principle is based on immersing a person in a specific environment in virtual reality. I can’t disclose the details yet, but for example, in the US, they use virtual reality to immerse a person in the events that caused their traumatic experience. If it’s a soldier, they might “find themselves” on the battlefield or in a trench. This is one of the methods of treating PTSD.

Will these developments also be available in Ukraine and abroad eventually?

Yes, we plan to export them as well. Perhaps they will first appear on the Ukrainian market and only later abroad, like VRNOW. Or perhaps we will launch them simultaneously on the Ukrainian and foreign markets.