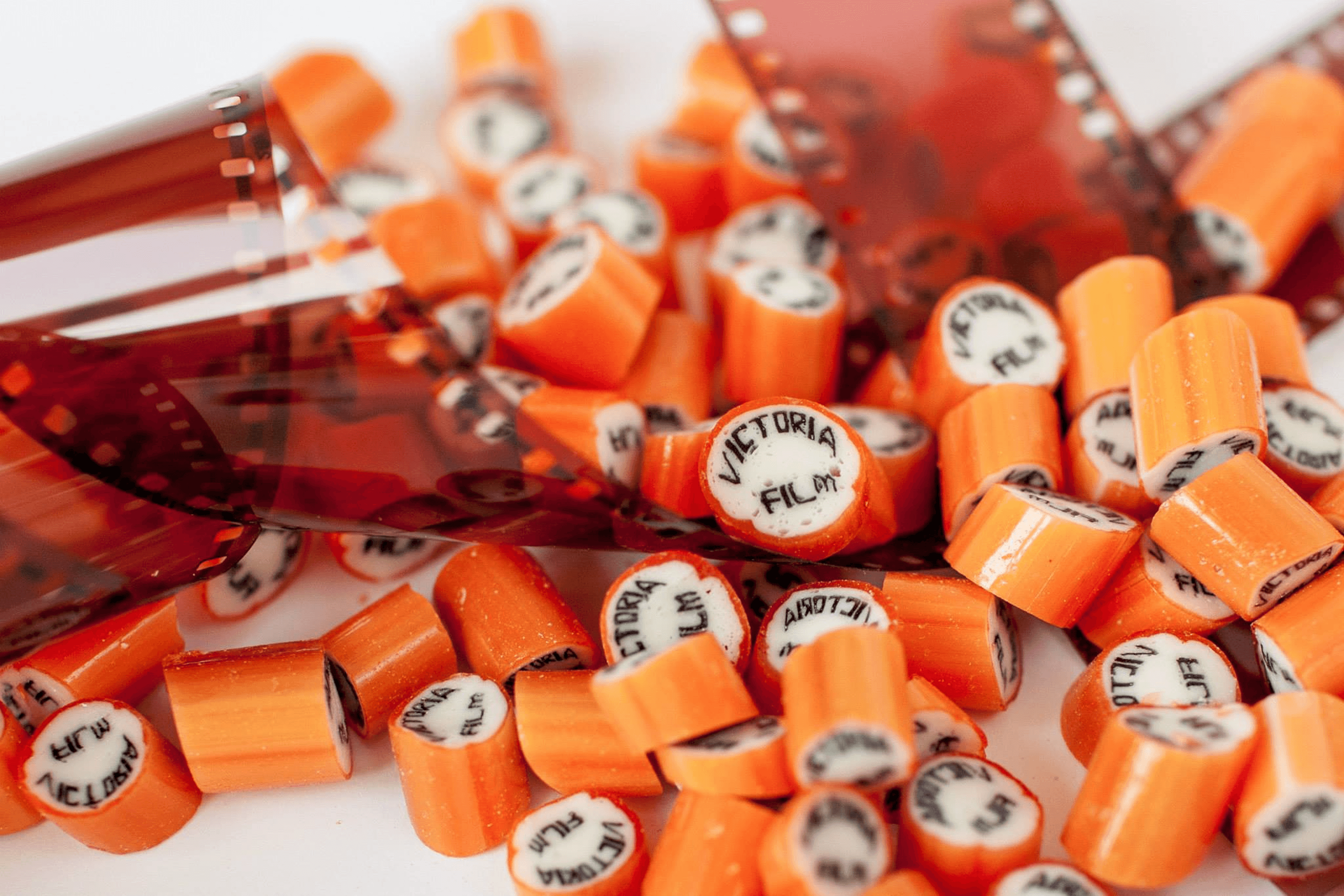

Olena Tokar is a 40-year-old entrepreneur from Kyiv who founded the craft brand of natural sweets Lol&Pop together with her husband, Dmytro, in 2013. The brand’s signature product, round candies with corporate logos embedded inside, quickly became popular among business clients, who order them as gifts for partners and employees.

Over time, Lol&Pop expanded its range and entered major Ukrainian retail chains. Since 2024, the brand’s products have also been sold in 350 stores of the Japanese retail chain Village Vanguard. In 2025, the company’s annual revenue totaled approximately ₴7 million.

Yellow Blue journalist Sofia Korotunenko visited the Lol&Pop production facility and spoke with Tokar about 13 years of building the business, exporting sweets, and the challenges caused by Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

1

Lol&Pop’s production facility is located on Kyiv’s Left Bank, on the ground floor of an apartment building. The entrance looks festive: railings painted red and white resemble a Christmas candy cane, while the glass doors are decorated with white stickers featuring the brand’s logo and images of candy.

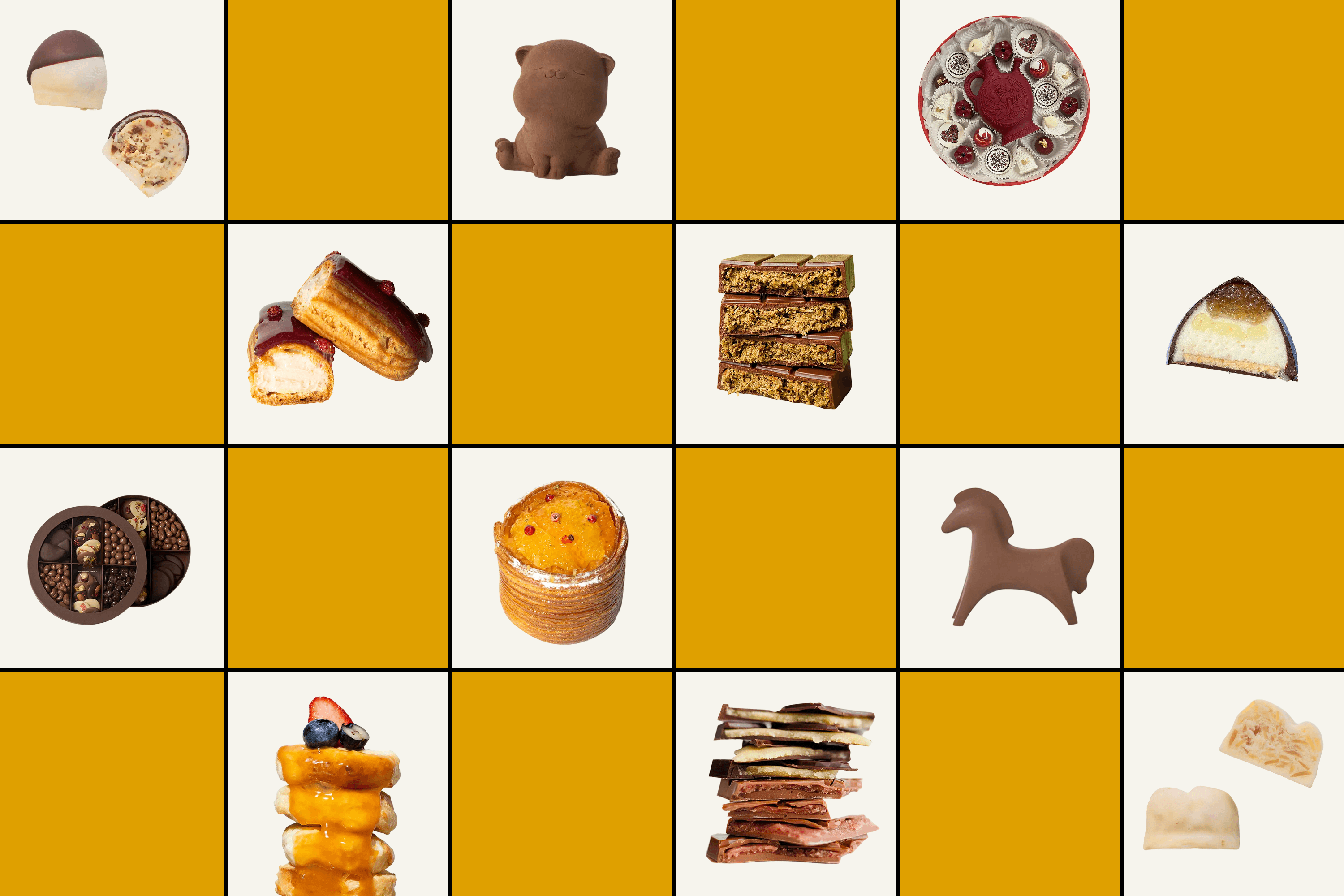

Inside, colorful figurines of candies, lollipops, and cotton-candy clouds hang from the ceiling. Gift boxes with Christmas designs line the shelves of bright display stands, alongside large stacks of packaging, stickers, and boxes of jellies. A large cardboard figure of the mascot stands nearby, a girl holding a lollipop, with candies woven into her pink hair. This character appears on all Lol&Pop packaging.

Olena Tokar, the owner of the business, gives us a tour. She’s dressed casually and holds disposable polypropylene gowns and caps. Without them, entry to the production areas is prohibited. Tokar says with regret that before the COVID-19 pandemic, the space had a shop and held workshops and children’s events. Now it’s a warehouse. While the war continues, the store will remain closed.

As always, Olena is short on time. She combines day-to-day work with regular trips to confectionery trade fairs across Europe, where she presents Lol&Pop products to foreign distributors. Until recently, she was also studying for her Executive MBA at the University of Toronto, which she completed in October 2025. At Lol&Pop, Tokar oversees international sales, corporate orders, and retail operations in Ukraine.

Lol&Pop began with caramel candies featuring images inside. How did the idea for such sweets come about?

I’m an economist, and I spent many years working in marketing at publishing houses. My husband, Dmytro, worked in a field related to IT. He’s an expert in server equipment. In 2011, our daughter Ivanka was born, and I wanted to spend more time with her. Looking back, it sounds naïve, but somehow my husband and I decided that starting our own business would give us that freedom.

We spent a long time thinking about what that business could be. One night, I accidentally came across a video of American entrepreneur Martha Stewart visiting the Papabubble candy store in New York. Confectioners kneaded caramel and stretched it into thin tubes before slicing it into rings. They created round candies, each with a heart image inside.

In the video, Martha said: “Instead of a heart, this could be a company logo.” And that’s when it clicked. This was it. Round candies with corporate logos inside didn’t yet exist on the Ukrainian market. Working in publishing houses, I’d seen how hard it was for companies to find original holiday gifts for employees and partners. This felt like a solution.

I woke my husband and told him we were going to make candies. Half asleep, he wasn’t thrilled, but later that day I explained the idea better, and he got excited too. So we started figuring out how to make them.

Why did you decide to use only natural ingredients in your sweets?

It’s important to me that my daughter can take any treat from our assortment, and I can be completely calm knowing she is eating something tasty, natural, and safe. Working with natural ingredients is harder and more expensive, but for me it’s a matter of principle.

Who taught you how to make candies with text and images?

I called many confectioners in Ukraine, but none of them knew how to make this kind of sweet. I reached out to entrepreneurs in the Czech Republic and the UK, but they either declined or didn’t respond. A company in Malaysia offered me a franchise for $100,000 under very strict conditions. Finally, I learned about a talented confectioner from Australia who made them and held workshops for people who wanted to learn.

In February 2013, we brought him to Ukraine. He’d never seen snow before and was delighted. We rented a space with special tables and equipment. Every day we learned something new, like creating complex images and text, and practiced our skills. The training lasted a month.

How much did you invest in Lol&Pop at the start?

About $50,000. The biggest expense was the training, his flights from Australia to Ukraine and back, and a month of accommodation in Kyiv.

Was this your own money, or did you get an investor?

We had some savings, but not much. I believed banks would gladly finance my idea. But reality was different. I went around with a business plan, and managers laughed at me. Nobody understood who would be interested in a product like this. They’d never seen it before.

We had to find another way. At the time, banks issued consumer loans easily and didn’t ask what the money was for. To start the business, my husband and I each took out loans. It was risky, with high interest rates, but it was our only option.

In the first years, the brand focused on the corporate segment. Why did you choose to develop this direction?

We didn’t have the budget for a large shop in a high-traffic area where we could sell candy retail. So I created a business plan for corporate clients. They don’t care where you’re based, as long as you respond quickly and deliver on time. My marketing experience helped me understand what they needed, and I had good contacts at many companies.

Another advantage of corporate clients is they always order in large quantities. To produce candies with a logo, you need at least four kilograms of caramel. Otherwise the image won’t come out right.

How did you find your first corporate clients?

We had almost no budget for marketing Lol&Pop. So we created a website and a Facebook page and offered BeFirst, a company that organized marketing conferences, to make free caramel candies with the event’s logo for one of their events. They agreed and posted about us. Within an hour, we received our first order from marketing agency Havas Engage.

It worked out exactly as I’d planned. Thanks to BeFirst’s post, many people became interested in our treats. After a few months, word of mouth kicked in, and we started receiving orders from clients I didn’t know, not even indirectly. We worked with event agencies and large corporations, including L’Oréal Paris, Intel, Dell, and Škoda Auto.

When did you realize it was time to expand the product range?

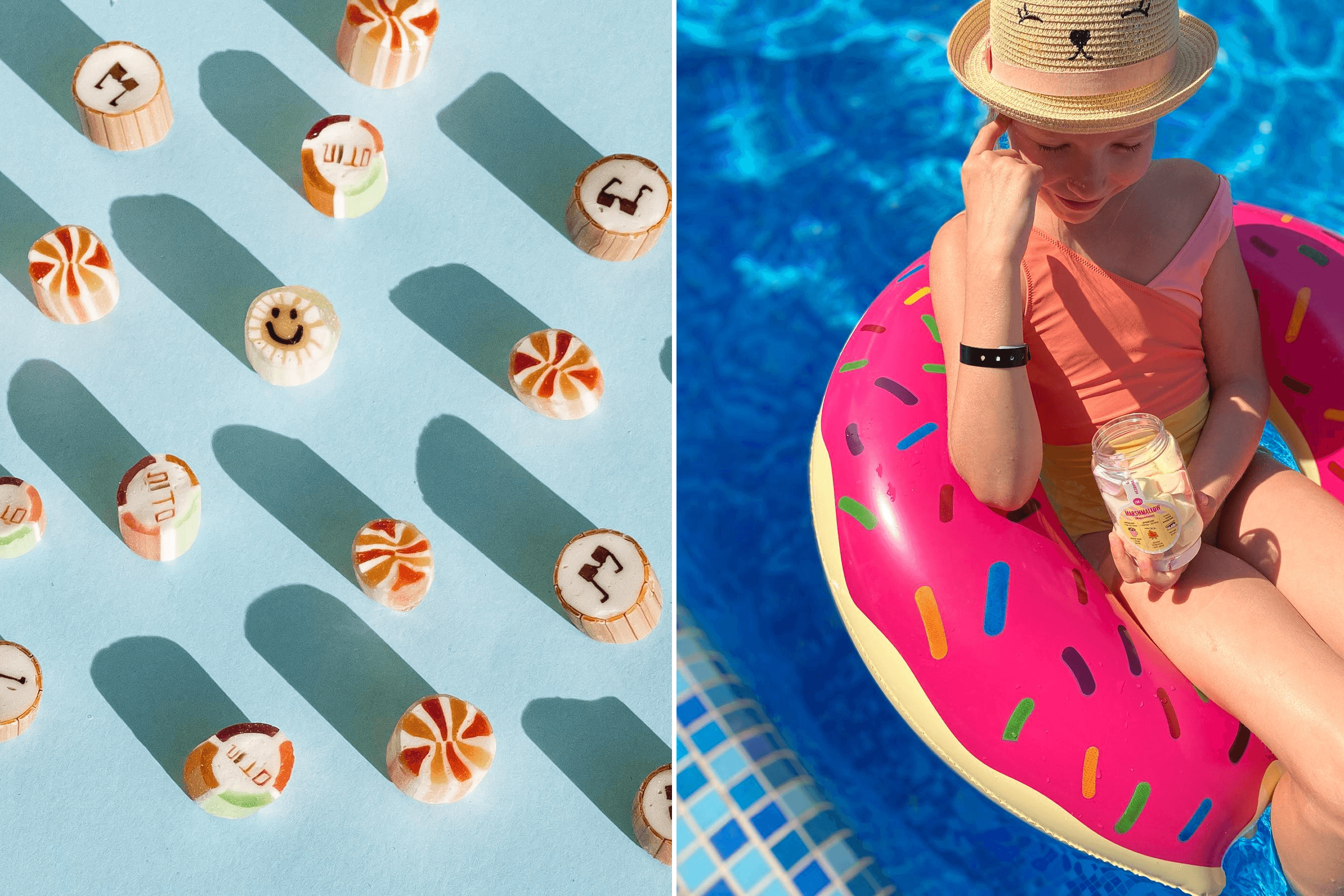

Our caramel sold extremely well, and during the first year we worked with many large companies in the Ukrainian market. But as a marketer, I knew that corporate clients rarely buy the same gifts twice. So we expanded the range, adding toffees, jellies, marshmallows, and lollipops. In 2014, almost no one knew what marshmallows were, so we included them for free with every order placed through our website.

You now sell your products in major Ukrainian retail chains, such as Good Wine. How did this partnership begin?

For me, Good Wine was something like the Tiffany store on Fifth Avenue in New York. We really wanted our sweets to be sold there, but it seemed impossible. In December 2013, right before New Year, one of our corporate clients said they had recommended us to a great contact. A few days later, I received a call from Good Wine’s purchasing department inviting me to come and present what we made. I couldn’t believe it. “Good Wine and me?”

I gathered all our samples, turned my charisma up to maximum, and presented our treats. They went through the tasting committee. People from different departments tasted them, commented on the flavors, and decided whether they’d buy them. They liked what we made, and in 2014 our products went on Good Wine’s shelves.

Our brand became much better known. Individual customers and corporate clients would buy from Good Wine, then come to our website and place orders. This really pushed our retail growth forward. Many stores looked to Good Wine’s product selection because of its strict quality and packaging standards. We didn’t knock on retail chains' doors. They saw us at Good Wine and approached us themselves. That’s how we ended up in Antoshka, Eco Lavka, and Wine Time chains.

Your production is handmade. Which processes do you not automate, and why?

We automate almost nothing. Of course, we have mixers for whipping marshmallow mass and stoves for heating syrup, but everything else is done by hand. This affects the taste. For example, our toffee tastes the way it does because we cook it in small batches. If it’s made in a large vat, it won’t cook down right. It won’t release enough moisture or thicken to the right consistency. For us, quality and natural ingredients are fundamental. These are our company’s values, and we don’t work without them.

We plan to automate some processes, like packaging or cutting marshmallows. But everything changes very quickly. Just as we prepare to buy automation equipment, an urgent problem comes up that needs immediate attention, like power outages caused by Russian shelling.

How do you divide management responsibilities with your husband?

Dmytro stepped away from the business in 2018 and returned to IT. Of course, I can ask him for advice, but this is my project, and I make all the decisions independently.

What’s most important to you when managing your team?

The key thing is to change as your business grows. I had to learn to delegate instead of habitually taking everything on myself, even when the scale already made that impossible. It wasn’t easy for me. But now I understand that employees can make mistakes and may not be very effective at first. That’s normal and part of the process.

You also need to build a team around shared values and open dialogue. In 2018, while working on a very large project, I lost 80% of my team. Some I had to let go, others left on their own. It was difficult and stressful, but it taught me a lot.

Finally, I built a strong core that has stayed with me through all the challenges. Now the team is seven people. Five work in production, two in management. We outsource some roles, like accounting and social media. I don’t think it would have been possible to adapt to COVID-19 and the full-scale invasion without this team.

Like many women in business, you combine work with motherhood. How do you manage everything?

I don’t. I alternate between being fully focused on business and spending more time with my child. My daughter is a teenager now, and I need to be there to support her or simply listen to school gossip. That’s important to me.

It’s not a problem if I don’t get something done at work or if I’m not involved in every process. But when I’m working on an export project, my daughter knows and understands that I may have less time for her. So no, I don’t do everything at once. I just try to prioritize.

2

Lol&Pop’s production facility covers about 200 square meters. It serves as an office, a small warehouse for finished products, and has three workshops: one for marshmallows and jellies, one for lollipops, and one for caramel candies. This is where products are made both for the Ukrainian market and for export.

Right now, three confectioners in aprons and bandanas are working in the marshmallow and jelly workshop. They stand at a stainless-steel table, removing colorful jellies from silicone molds and rolling them in powdered sugar. On a nearby table sit large plastic containers filled with rainbow-colored marshmallow mixture, tightly sealed with lids. Later, they will cut this mixture into small pieces. To color the marshmallows, they use natural extracts like blackcurrant, paprika, vanilla, and black carrot.

In 2015, you began expanding through franchising and opened locations in Zaporizhzhia, Poland, Israel, and Bulgaria. But three years later you closed everything down. Why?

My husband and I had no experience, and we made a strategic mistake. Instead of supplying franchisees with finished products on favorable terms, we sold them the production technology. We believed they would follow all our standards and use only natural ingredients. But that didn’t happen.

The first store opened in Zaporizhzhia in 2015. Later, we began receiving inquiries from Europe, but we didn’t understand how to do business there. We decided to open a location in Poland, in Krakow, so we could go through all the stages of working abroad ourselves. We didn’t analyze the market properly. We should have spent at least a few weeks living in the city, talking to locals, and understanding how people shop. That would have saved us a lot of money.

In 2017, we closed both the store and the production facility in Poland because the local market wasn’t ready for us, and we weren’t ready for it. At the time, there was a strong trend toward natural products in Ukraine, but Polish consumers didn’t understand why they should spend 8 zlotys on a small pack of jellies when they could buy a kilogram in a supermarket for the same price. You can’t simply take a Ukrainian business model and apply it to foreign markets. You have to adapt everything to local habits and expectations.

It was an interesting experience, and I don’t regret it. I learned Polish and understood all the nuances of doing business abroad. Thanks to that, we sold franchises in Varna, Bulgaria, and Ramat Gan, Israel. Those locations operated for two years, but eventually I realized I wasn’t happy with what they produced or how they worked. I closed all the franchise locations and focused on exports. That way I could guarantee the quality of every product sold under my brand.

You received your first export proposal from the U.S. in 2020. How did you find a distributor?

That came after I attended a training program at the Export Promotion Office, run by Ukraine’s Ministry of Economic Development and Trade. Before that, I didn’t understand how exports worked, how to build logistics, or what certifications were required. Between 2017 and 2019, I went on trade missions to Israel, Austria, Switzerland, and Germany. Together with other Ukrainian entrepreneurs, I met foreign distributors who shared their experience and evaluated our products.

During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, we were going through a difficult period, barely surviving. In July, an acquaintance told me she knew an American distributor who was opening a large children’s store called Hey Joy in Minnesota. He became interested in our candies, and within a week we sent him samples.

We weren’t ready for international sales. During the program, we were told that the U.S. shouldn’t be the first export market for producers as small as we were. But in life, anything is possible. We had an inquiry, an order, and we had to make it work. We optimized our processes and hired seasonal workers because we had to meet a very tight deadline. In September, our first pallets were shipped to the U.S. I couldn’t believe it.

A few weeks later, he placed another order. They sold well. Through the same partner, our products were sold in the TJ Maxx and HomeSense retail chains. This continued until the end of 2021.

How did Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine affect your cooperation?

We were supposed to ship the next order in February 2022. That never happened. Shortly after, he revised his business model and stopped ordering from us.

What have been your main challenges during the full-scale invasion?

There have been many. People began spending less money on sweets, while raw material prices keep rising with every new order. It’s difficult for us to adapt our financial model to this growth. We work in retail and can’t raise prices every week. Our contracts with retail chains specify that price changes are possible only once a year or once every six months.

The summer of 2025 was the worst in all the years we’ve been operating. Our sales dropped by more than 60%. Summer generally isn’t the best season for candy sales, but earlier we compensated for the seasonal downturn through exports or special orders for events and companies. This summer, that didn’t work.

It wasn’t until mid-October that we started getting back to spring figures. We still don’t know what challenges we’ll face in 2026. These issues affect not just our production or our industry. This reflects broader trends across the country.

Has it become harder to source natural ingredients because of the war?

We purchase natural extracts for our candies abroad through Ukrainian distributors, and sometimes their trucks are delayed at customs. When that happens, certain flavors drop out of a production batch.

But the biggest problems involve ingredients produced in Ukraine. For example, glucose syrup. In 2023, factories couldn’t produce it in the necessary volumes because of large-scale power outages. Glucose syrup nearly disappeared from the market, and prices rose sharply. We had some reserves stored at a supplier’s warehouse, but shortly before the winter holidays, that warehouse was hit by a Shahed kamikaze drone, and we lost part of those reserves. It was a difficult time. Now things have stabilized. Factories have resumed full operations after purchasing generators. Ukrainian entrepreneurs adapt quickly and find new solutions to keep working at a normal level.

3

In recent years, Lol&Pop has stopped producing its signature caramel candies, the products the business started with back in 2013. Their production is physically demanding. A thick, sticky caramel mass is kneaded by hand using a special hook, rolled out, combined by color to create an image, stretched into thin tubes, and then cut into rings. Men used to do this work, but because of the war there’s now a shortage of them in production.

So the caramel workshop has been turned into a storage space. On stainless-steel tables stand boxes of various packaged lollipops, including maracas-style ones, which Lol&Pop spent about a year developing. These candies are made of two isomalt plates with edible blue sprinkles inside. When you shake them, the sprinkles move and make a rattling sound. They became popular in Japan and now sell in the large retail chain Village Vanguard, known for unusual designs.

In October 2024, the first batch of your sweets went to Japan and appeared on Village Vanguard’s shelves. How did you find a distributor, and what attracted them to your product?

In February 2024, we attended the ISM confectionery trade fair in Cologne, and a distributor from Japan was among the first to approach our booth. I honestly didn’t think we could interest them. That market seemed almost unreachable to me, a place where you can find absolutely anything.

But a week after the fair, we received an email asking for our quote. I sent samples three times, we negotiated pricing, and after eight months we made our first delivery.

Shortly after, posts about our candies began appearing on Village Vanguard’s social media. I was surprised by how different they were from what we were used to, very bright, with big bold text. Sometimes customers write to us, praising what we make and asking whether everything is okay with us during the war. Some translate their messages into Ukrainian using translators.

What are the specifics of exporting there? Did you change the ingredients or the packaging?

We had to prepare a large number of documents, describe the production process, provide process charts, and submit a full list of ingredients. Our labels were translated into Japanese, and the distributor checked the text.

Samples went to laboratories several times. All the lollipops passed testing except one, the version with red sprinkles. The lab found traces of a dye that’s banned in Japan. We quickly found an alternative and sent a new sample for testing. This time, everything passed.

Do you face any logistics challenges?

Our products fly from Warsaw to Tokyo with a transfer in Dubai. Crossing the Polish border to deliver the goods to the airport is extremely difficult. Polish border officials cite vague reasons and do everything to block the shipment. Our first shipment was turned back at the border. The driver had to reach Warsaw via Hungary, even though all documents were in order and no rules had been violated. Now we transport goods through Hungary. It’s longer and more expensive, but at least it works. This problem needs to be solved at the state level.

Japan has fierce competition and many creative designs. What makes your sweets stand out?

Our candies are bright and have an unusual shape. Another advantage is that we’re not in the mass market, but in a more premium segment. Village Vanguard is a chain where people can find unusual items with crazy designs. People come there for new emotions.

Consumers there like to give small gifts to one another and add something interesting to lunchboxes. We want to ship jellies in three-packs, so parents can put a single small pack into a child’s lunchbox instead of taking sweets out of a large bag. When you understand the market and local preferences better, it becomes easier to adapt.

What are your export plans?

We’re currently looking for new partners to get our products back to the United States. We already have FDA certification and experience in that market, so we know how it works. We’re also working on expanding to Canada.

In Japan, we currently have three possible clients. Recently, I met with one of them, a large importer, Kobe Bussan. We can’t offer them the lowest price, but we have products no one else does. I think that works in our favor, though we’ll see how the negotiations turn out.

What advice would you give Ukrainian entrepreneurs who want to export?

Learn from other entrepreneurs' experiences, but don’t let them stop you. Export has rules, but there are always exceptions. Don’t listen to people who say something is impossible without first checking if it’s true. If it didn’t work out for someone else, that doesn’t mean it won’t work for you.

And know that exporting is not a magic solution that will quickly bring in foreign currency. It’s hard, long-term work that takes energy, effort, and money.