Ivanka Nebor, a 29-year-old Kyiv native, is an otolaryngologist who is in her third year of residency in a New York suburb. Her working day at the hospital can last from 12 to 24 hours: every day she examines dozens of patients and performs numerous surgeries. The residency was preceded by five years of research work at American and Canadian universities. And also by preparation for difficult exams, thanks to which Nebor secured a spot in the program for which more than 200 people applied.

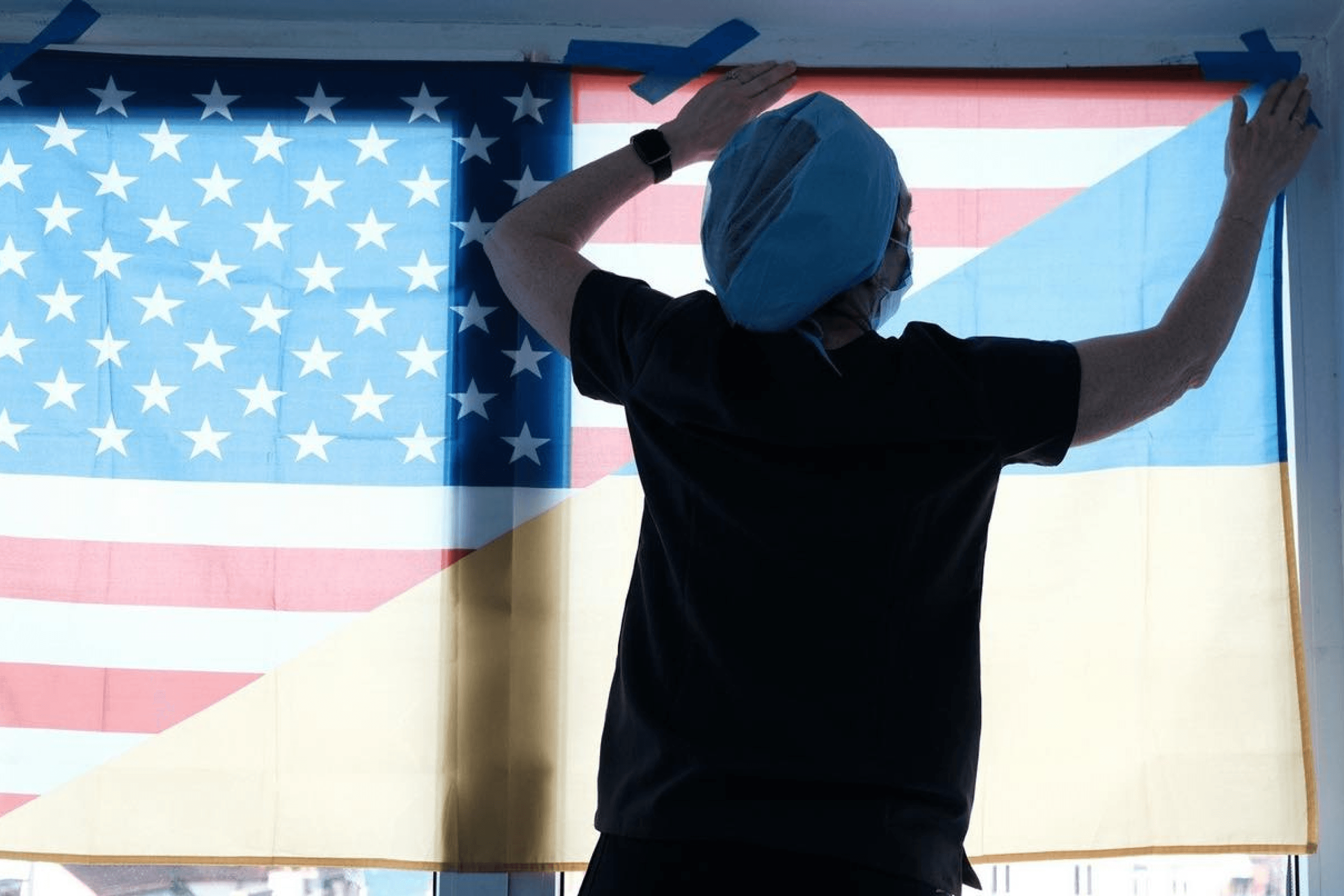

In Ukraine, since 2016, Ivanka has headed the medical platform INgenius, which for a long time was the only Ukrainian-language professional publication for medical professionals. Since 2022, Nebor has been organizing the Face to Face humanitarian missions, during which American doctors and nurses come to Ukraine and gratuitously restore the faces of Ukrainian military personnel and civilians who have suffered from hostilities. Such complex operations are unique across Europe.

Sofiia Korotunenko, a journalist for the Yellow Blue Business Platform, spoke with Ivanka about her path in medicine, research, residency in the States, and volunteer projects in Ukraine—INgenius and Face to Face. Here is what it’s like to be a Ukrainian doctor in the USA.

1

Why did you choose the field of otolaryngology?

When I was studying at Bogomolets National Medical University, I liked surgery because you see the result immediately. You come, see, cut out, help. This is for restless people who cannot wait long. We joke in the medical world that real doctors are therapists, not surgeons, because surgeons just want to cut, and therapists truly want to treat.

Otolaryngology is interesting because patients are more sensitive to everything related to the face. In Europe, this specialty is more isolated to the ear, throat, and nose (ENT), but in the USA, it is broader and more complex involving more head and neck pathologies. This is very delicate surgery: you need small glasses to see everything. I have always liked that very much.

Tell us about the medical platform INgenius that you founded.

INgenius appeared in 2016, a few years after the Revolution of Dignity. There was a wave of interest in Ukrainian products, but in the medical community, all public pages were Russian-speaking and published content on the Russian social network VKontakte. My friends and I decided to create a website with high-quality, professional content in the Ukrainian language as an alternative to Russian-speaking public pages. We were meticulous about the content and created stylish visual accompaniment. What the universities in Ukraine were doing was conservative, but ours was interesting and colorful. That’s how INgenius appeared.

Then we began to hold events for the medical community about evidence-based medicine, vaccination, the correct prescription of antibiotics, and also about drugs that actually don’t work. Now these are common things, but in 2016–2018, this was not the case. INgenius took off. We cooperated with the Ministry of Health and fought against non-evidence-based medicine. During the COVID-19 pandemic, we debunked fakes.

How do you finance INgenius?

For the first four years, it was exclusively volunteer work. Now we have both volunteers who are interested in writing articles, and grant projects, where donors help us cover a specific topic. Work at INgenius is our hobby, the volunteering that we love.

In general, INgenius develops along with us. We started doing it as students, so it was more interesting to interns and young doctors then. Now we create content according to our professional level and share what is relevant to Ukrainian society.

How does INgenius work during the full-scale invasion?

Many people from our team joined the ranks of the Armed Forces of Ukraine and became military medics. Now the rest of the team is creating protocols for family doctors and neurologists who work with veterans. Our protocols for physical and psychological rehabilitation of veterans have already been approved by the Ministry of Health.

We are also working on a project about chronic pain among veterans and incorrect ways to treat it. For example, when narcotic drugs are incorrectly prescribed, and veterans develop drug dependence. We also plan to cover the prevention of postoperative infections and the problem of antibiotic resistance.

INgenius is also working on the large-scale Face to Face project—plastic surgeons from the USA restore the faces of Ukrainians who have suffered from the war free of charge. How did you organize the first mission?

In the summer of 2022, doctors from the American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery contacted the charitable foundation Razom for Ukraine. A neurosurgeon and one of the fund’s leaders, Luke Tomich, called me and told me that they wanted to come to Ukraine and help wounded soldiers.

The INgenius team reviewed all applications and presented the patients to the American doctors. I found a hospital in Ivano-Frankivsk, and the local doctors welcomed our team very well and organized the entire process of working with patients. Everything went great. We organized all of this in two months, which is very fast and a little crazy.

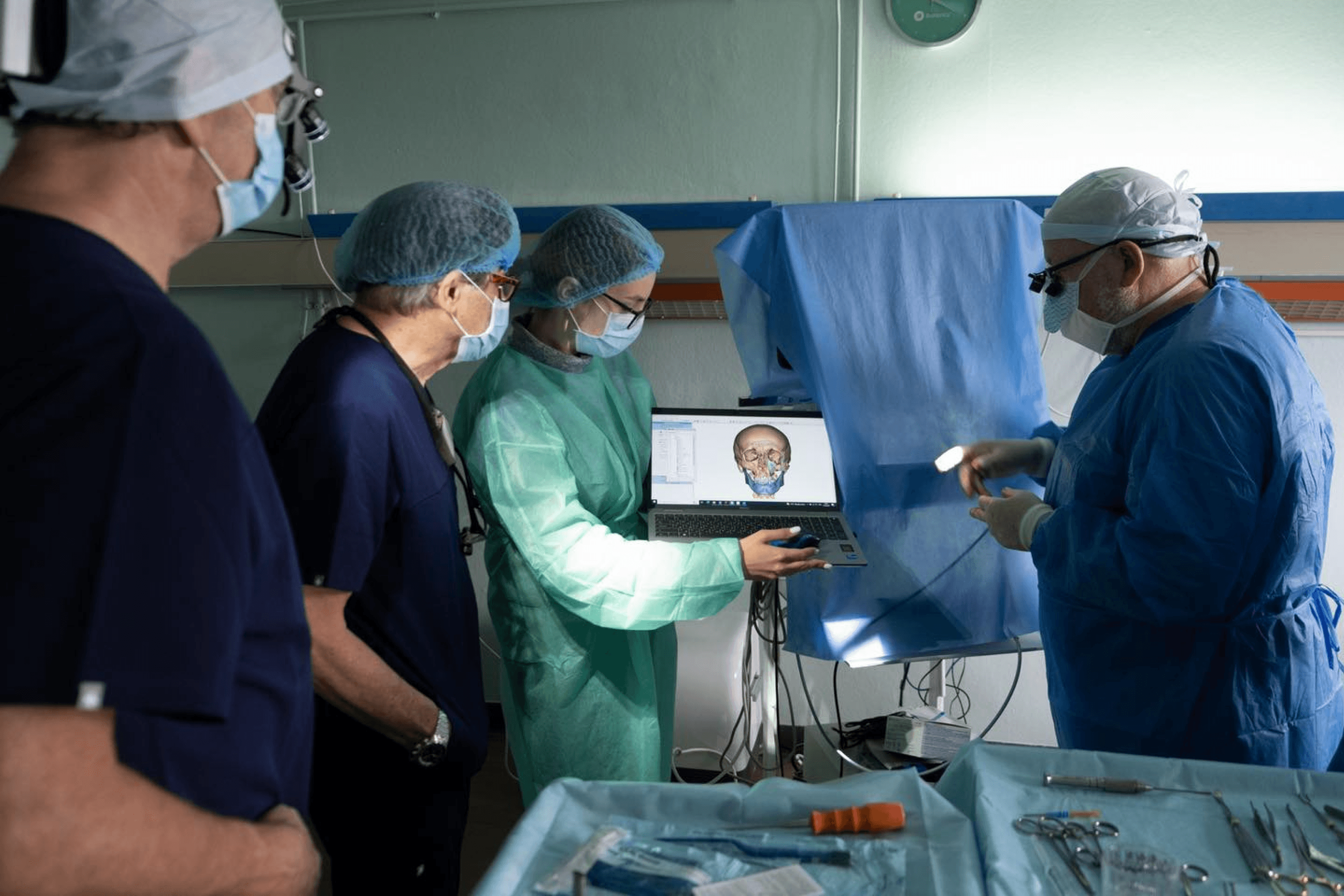

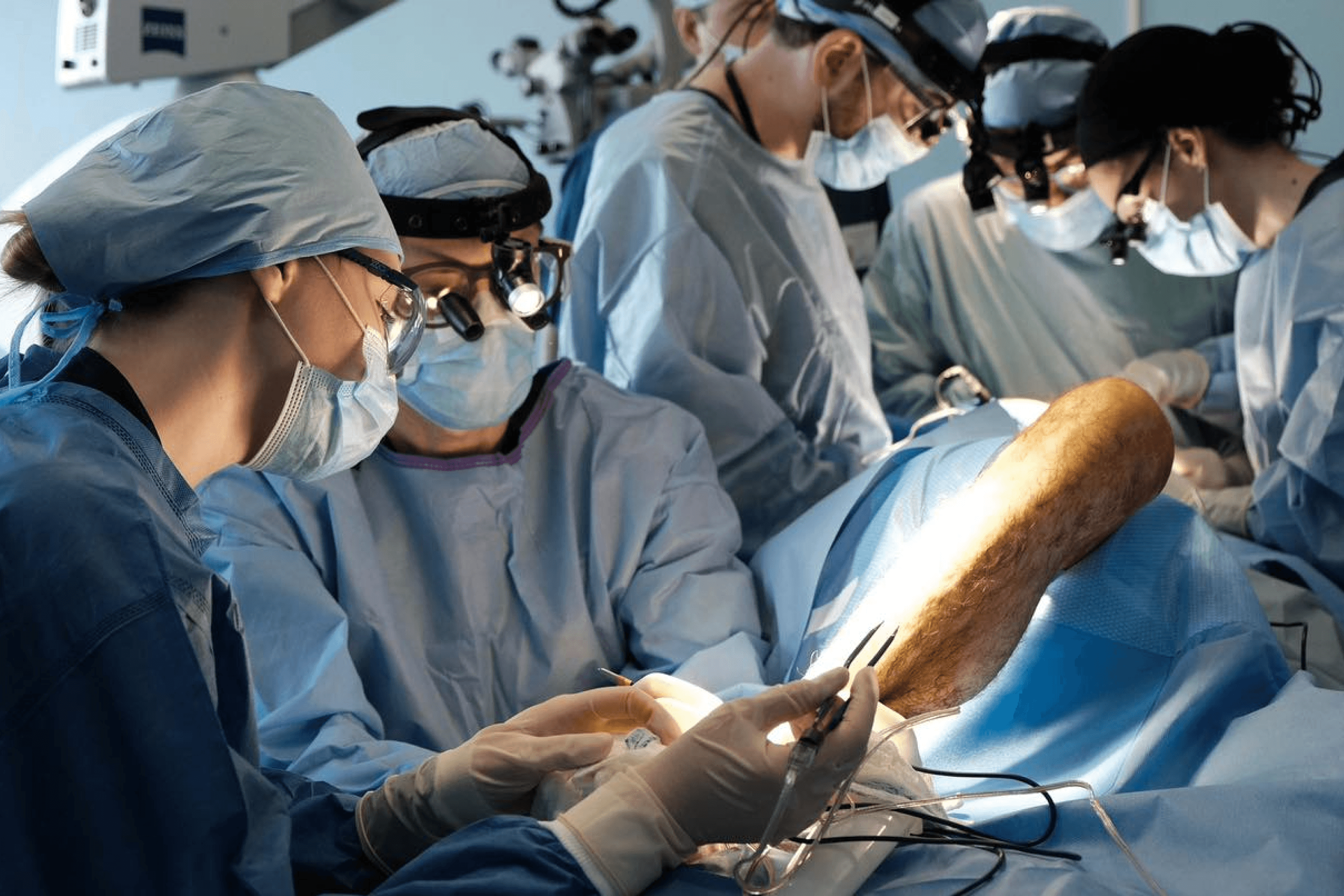

The Americans liked it very much, and they decided to return again. We held all subsequent missions in Lviv. Face to Face has already operated on approximately 150 people. A third of our patients are those who return for a follow-up to correct previously performed operations or to treat another part of the face. Now, in 2026, our sixth mission will take place.

How do you prepare for new missions?

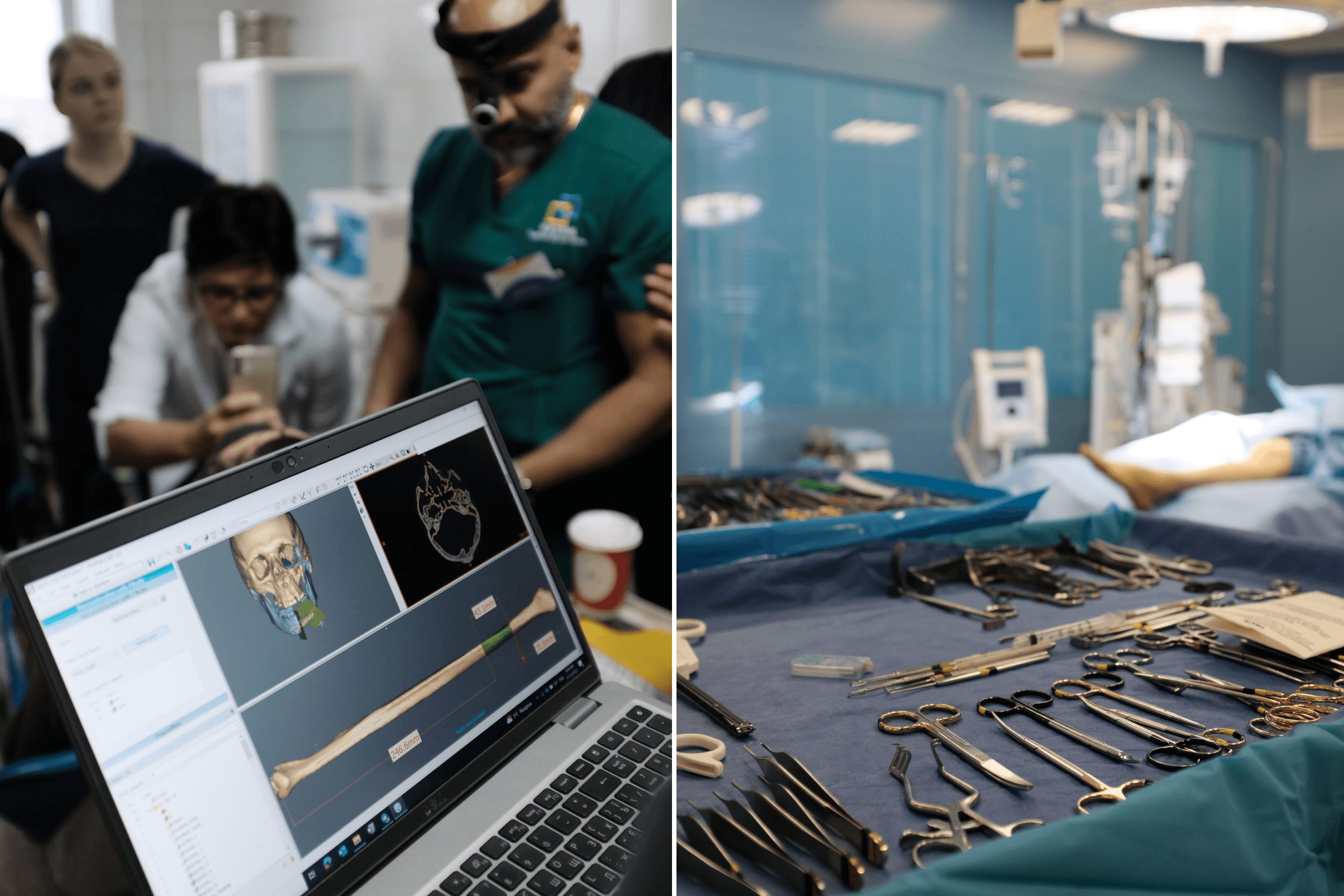

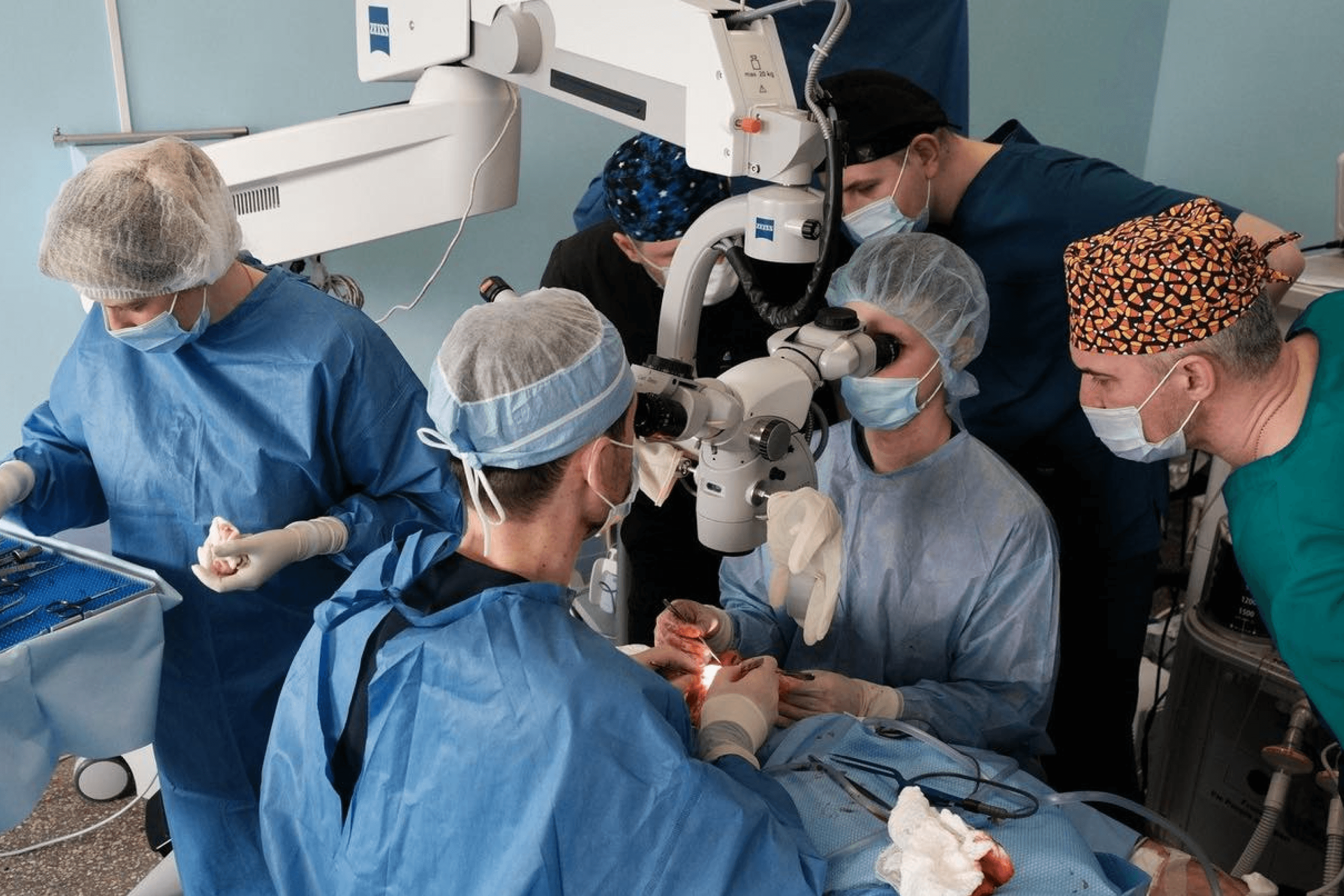

To perform 30–35 complex operations, we collect specific materials, buy expensive thin threads and various eye implants, bring equipment, and order custom titanium components. They are printed for us free of charge by the company Materialise because Ukrainian IT specialists work there. This is a very expensive technology: they use the patient’s computed tomography (CT) scans and print the implants.

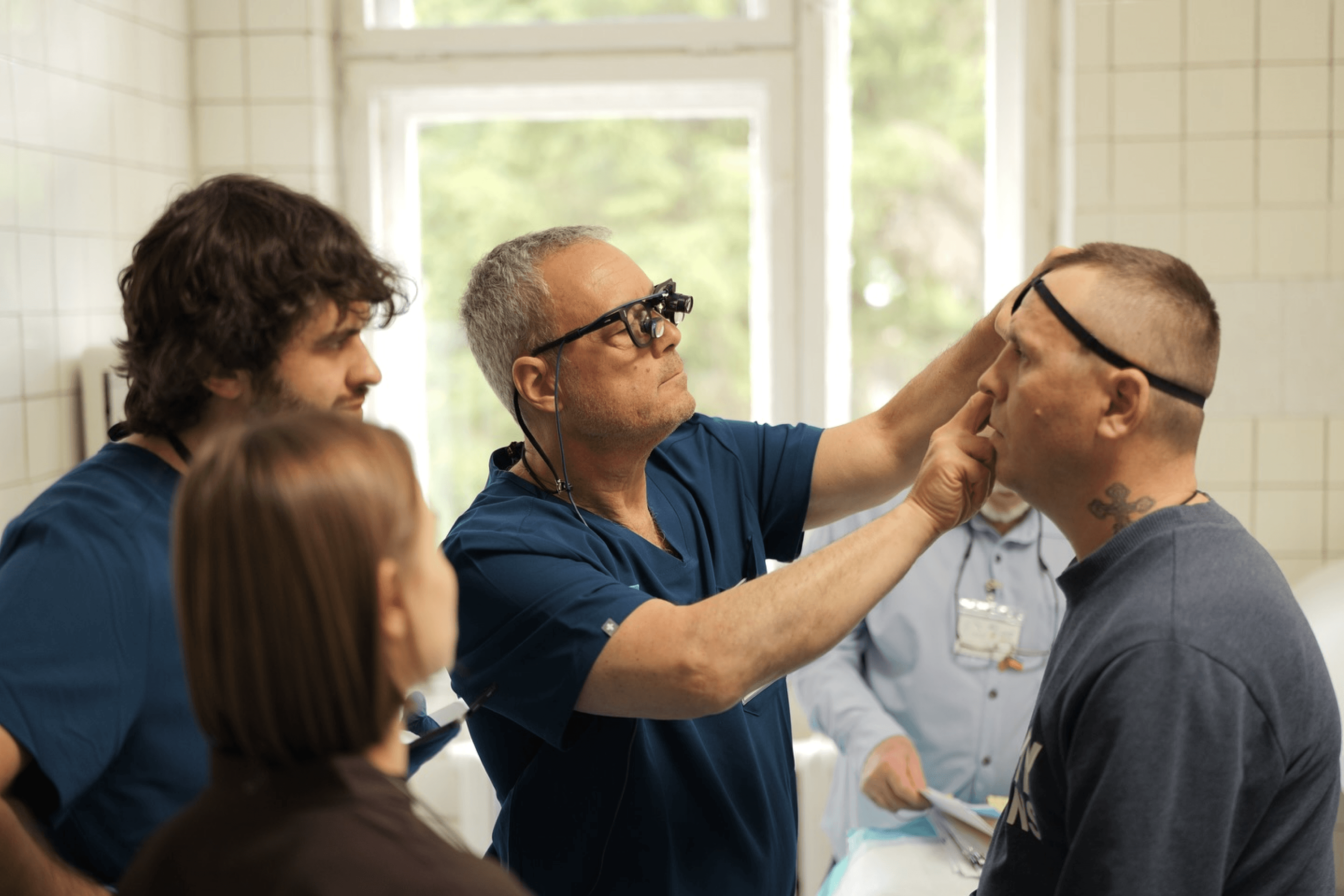

Every two weeks for six months, we analyze the patients' photographs and CT scans and draw up an operating plan for the week. But when we examine the patients on Sunday, the first day of the mission, the operating plan changes: some patients are added and some are canceled. It’s a huge rush—very difficult.

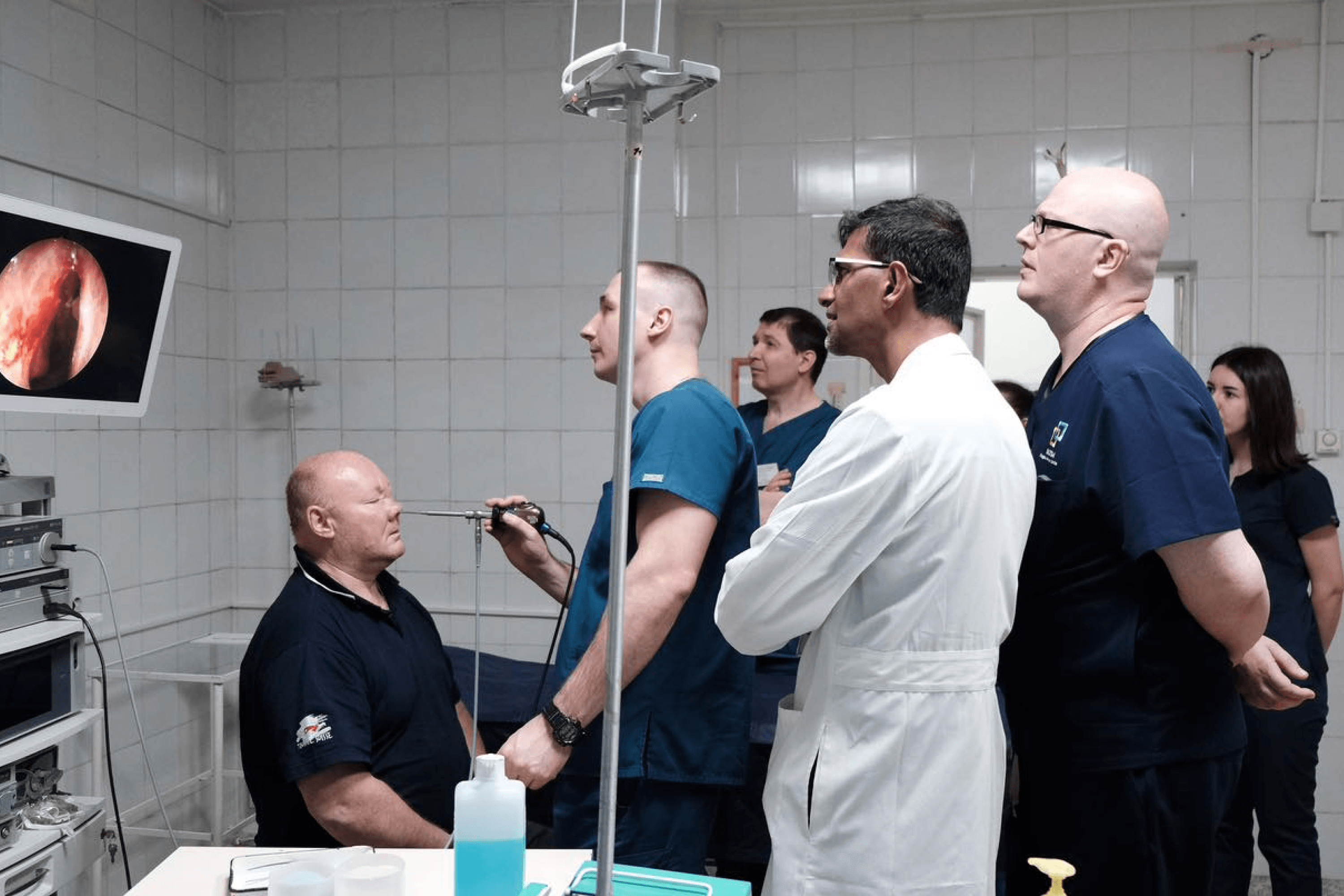

Do Ukrainian doctors participate in the operations?

Yes, Ukrainian doctors learn and gain experience so they can operate independently later. American doctors won’t be able to operate on all patients in Ukraine. And the training of our doctors is also an important goal of this project.

Are Face to Face patients only military personnel?

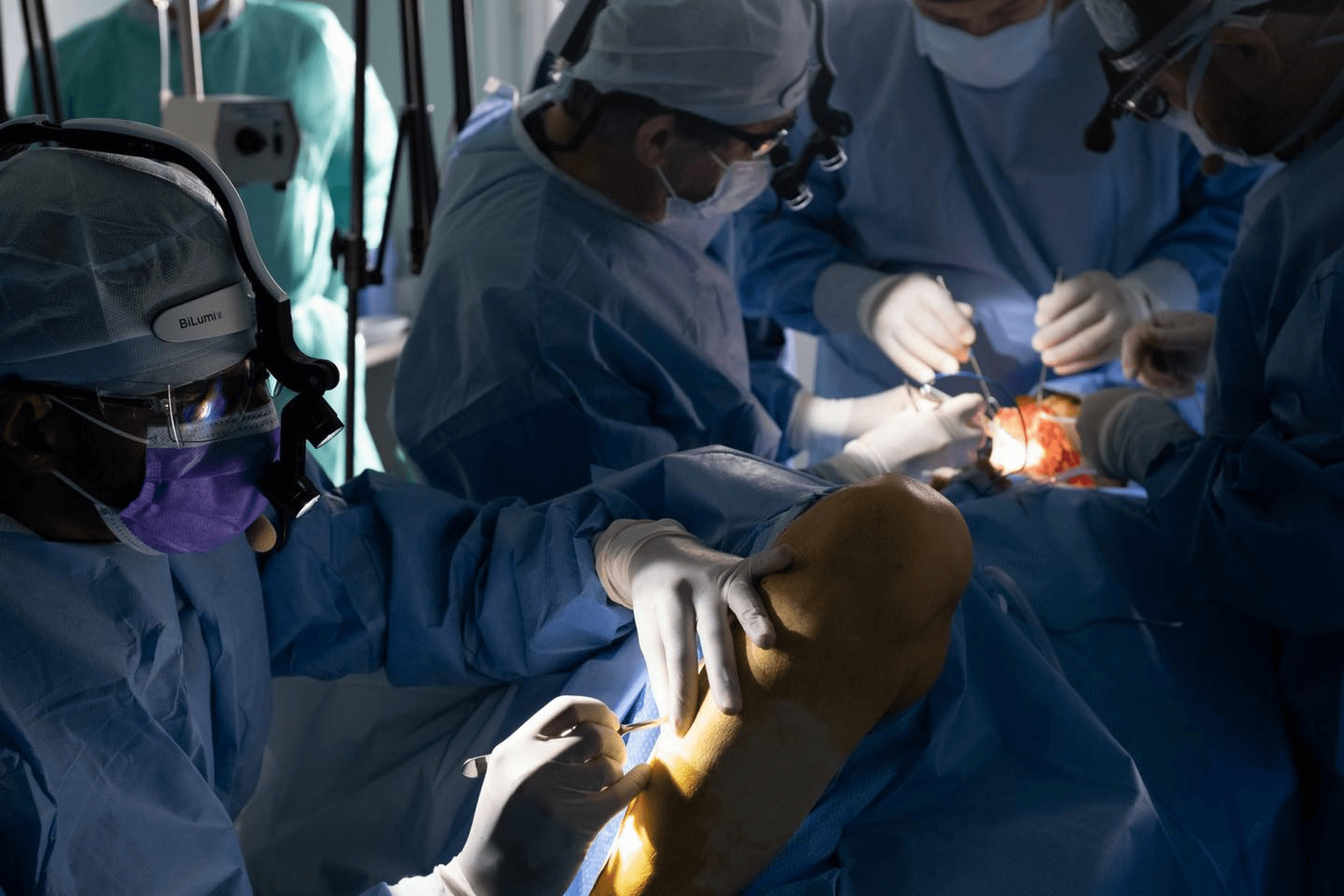

They can be civilians who have suffered from the war, but most patients are military personnel with serious injuries; during one mission, this is about 30-35 people. This project is very difficult, we try to communicate carefully with patients because surgeons aren’t gods, we cannot make everything perfect. Sometimes we understand that we just need to do a face transplant, which we cannot do. It is impossible to return everything to how it was [before the injury], but in many cases, breathing or the appearance of the nose or jaw can indeed be improved.

What is the main specialization of Face to Face?

These are unique jaw reconstruction surgeries that last 13–15 hours. We transplant tissues and bones from the legs to the face. We need to connect various vessels from the transplanted donor part to the recipient part of the face. Therefore, it is a painstaking and difficult operation performed under a microscope. Such operations are not performed in all European countries, but in the USA, this is a standard practice in many hospitals.

During our sixth mission, we will focus on facial paresis. This is when an injury affects the facial nerve and paralyzes part of the face. This paresis can be corrected by transplanting nerves from the leg or neck to restore at least some function of the facial muscles. Such operations are not performed in Ukraine.

What impresses foreign doctors the most during your missions?

Americans are surprised that our patients are ordinary people. Because their military personnel study at the academy and build careers in the army. We always ask [our Ukrainian patients] what they did before the war. Someone sold electronics in their own shop, someone had a coffee shop in Rivne, someone worked as an IT specialist. The scale of the injury also impresses them—the number and nature are very serious. Patients often send their photographs from before the war and before the injury. No matter how long you work in medicine, you are still human, and such sensitive moments affect you.

Which organizations finance the Face to Face missions?

Trips and materials are covered for us by the Razom for Ukraine foundation. Equipment and travel for nurses are paid for by Healing the Children. American doctors and nurses work for free. There are also specific sponsors for certain needs, whom we list on the INgenius website: our nurses and doctors contact them, and these companies donate threads, various instruments, implants, and other supplies to us. These are Stryker, Ethicon, and Materialise.

2

You are currently in your third year of residency at an American clinic. This was preceded by a long path—regular internships abroad and research activities. When did you first come to study in the USA?

In 2018, I completed internships at two clinics in two months—at Cornell University in New York and Rutgers University in New Jersey. To get such clinical internships, you need to find a professor who will accept at their university. For a doctor, the States are one of the best places to study and work because they offer access to the best tools, equipment, and training.

What impressed you the most during the internship?

The work of the doctors was striking—senior residents performed operations that in our country only professors could do, and not all of them, only in advanced departments in big cities. Such operations are considered 'rocket science' in Ukraine, although for American residents, these are ordinary things. I really wanted to become like them.

How long was your journey to residency in the USA?

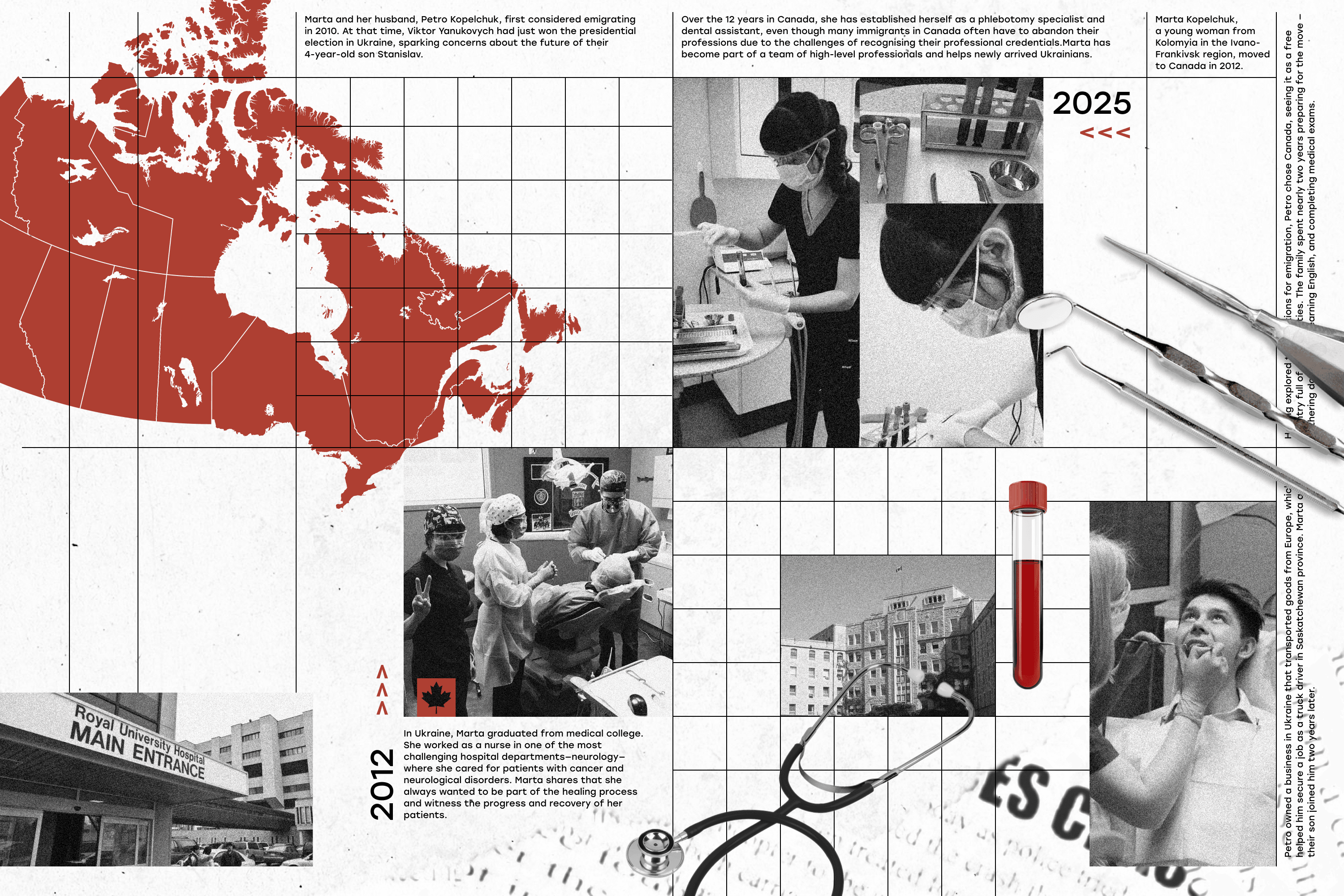

[After the first internship in the USA] I returned to Ukraine, finished my internship at Oleksandrivska Hospital, and in 2019, I started postgraduate studies at the Institute of Otolaryngology.

Later, I got into a research fellowship program that focused on skull base surgery—and spent four months at the University of Cincinnati. This was my most interesting research work. We learned to perform surgical approaches on cadavers and conducted anatomical studies to make scientific publications.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, I applied for a position as a clinical research physician at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital—one of the best children’s hospitals in the States. In the otolaryngology department, they perform unique, rarely seen operations. At the same time, I studied for the exams that make it possible to apply for residency. The selection process for it lasts about a year.

In 2022, I went for a year to a clinical rhinology fellowship in Canada, at the University of Western Ontario. It was not so much research work as work with patients, so the selection for this program was more serious. Research work and practice in Ukraine are important to the professors. It was a great experience.

In 2023, you became a resident at Westchester Medical Center, a hospital in the New York suburbs. How difficult was the selection?

It is very difficult to get into residency, especially for foreigners. In my program, there were about 200 candidates for this one spot. This is a very rigorous selection process. Even if everything about your application is perfect, they have to like you as a person so that they can work normally with you for five years.

Otolaryngology is one of the most competitive specialties, with approximately 320 spots for the entire United States. Only 320 ENTs graduate every year in a country with 350 million people. Therefore, each otolaryngologist covers a very large population during residency training. Because of this, the residency is very stressful, we operate on and serve many patients.

Our normal schedule is 80 hours a week, but it is often more. Not only do you have to work clinically—doing rounds and operations—you also have to study a lot in the evening to prepare academically. You can’t just come and repeat the doctors' movements like a monkey. You have to understand what you are doing.

How many years does the residency last?

In a surgical specialty, it usually lasts five years. My third year has already begun, and I have personally felt how difficult it is. You try so long and hard to get this residency, and then you suffer and say, “My God, why is it so hard?” But there is a light at the end of the tunnel.

What does a typical day for a resident look like?

I wake up at 5:00 AM and go to work. The day begins with the on-call resident reporting what happened overnight with each patient. This lasts about 30 minutes. We write everything down and do rounds. Operations last from 7:30 AM to 6:00 PM. Large operations can last until 9:00 PM.

Between operations, you can do small procedures—drain an abscess or look at a patient’s throat with a camera. On a normal day, I operate until six, then discuss with other residents what is happening in our department, what consultations there were, and what else needs to be done—and at 7:30 PM, we usually go home.

A month ago, I was on my feet for more than 24 hours. After the morning rounds, we had a presentation of reports and a lecture, and from 8:00 AM to midnight, we worked in the operating room. I was also on call that day, which meant I had to see several patients waiting in the emergency department.

After the call, we go home to get some sleep; this is called a post-call day. In a month, we only have one normal weekend, meaning both Saturday and Sunday. We call this the Golden Weekend. Otherwise, we work non-stop.

What is the difference between Ukrainian internship and American residency?

These are different forms of training. In the USA, the first year of residency is called an internship. You operate minimally and help maximally with ward work. From the second year of residency, you work as a full-fledged doctor: you independently examine and operate on patients. Of course, you discuss everything with your mentor, attending doctor, but other doctors perceive you as a full-fledged doctor.

In Ukraine, an intern is not taken seriously—you cannot manage patients or perform operations. Interns are not responsible for anything, but in the USA, a resident has malpractice insurance. If something happens to a patient, it can cover their mistake—including the legal fees and all side effects that may occur to the patient. In Ukraine, the doctor is responsible for everything, including criminal proceedings. They are not protected and cannot entrust an operation to an intern, no matter how much they would like to. This should be regulated by law much better.

Also, in the US system, there is no financial interest of the doctor in the patient. You never know how much you are getting for treating somebody. In Ukraine, the doctor takes money for services directly from the patient, so it is very difficult for them to entrust a stage of an operation to an intern. Because of this, the intern’s training suffers greatly. Residency is a completely different world, not thanks to the people, but because the system is built that way.

Given your experience in the USA, what would you like the Ukrainian medical system to adopt from there?

The transition to an electronic system—and it’s great that it has already begun in Ukraine. During my studies in Ukraine, I saw how poorly all those papers work. I know that many Ukrainian colleagues hate the electronic system, but all Americans do too. However, it works—it standardizes and controls everything, which is especially important in criminal cases. If something happens, the electronic system can protect the doctor. Because electronic medical records cannot be rewritten, but paper ones can.

The residency experience should also be integrated. Training is the first thing that must change in the Ukrainian system. Wages also remain a big problem, although I know that the situation is better now than it was 10 years ago.

3

Is it difficult for Ukrainians and other foreigners to integrate into American society?

No matter where you live, it is difficult to integrate because there is a difference in culture and language. I’ve been living in the States for five years, and it is still sometimes hard for me to express thoughts in English; I cannot speak freely on all topics. But everything related to medicine isn’t a problem for me. However, I’m grateful to this country for the opportunity to learn so much and develop. I think that when you are focused on your goal, life in a foreign country becomes easier.

What is the most valuable thing you gained through working and studying in the USA?

Great personal growth that was worth a lot of effort—I improved my English, learned to write correct and good research papers, and passed all the American exams. This requires perseverance and discipline, you simply force yourself to sit and study.

I also understood my limits and maximums. When I entered residency, I thought my path was over. That I had dreamed about it for so long, worked towards it for three years—and now I finally can enjoy life. But this only turned out to be the beginning of a new path; my personal growth continues. This experience allows us to look at life differently and go beyond our limits.

How does your experience in the USA help you manage initiatives in Ukraine—the INgenius platform and the Face to Face missions?

In INgenius, thanks to the American experience, I come up with interesting projects that are not yet available in Ukraine. In the Face to Face mission, understanding the two systems helps to connect the American and Ukrainian teams so that we can help patients together. This is not only a language barrier but also a different approach to work. Therefore, without my experience, it would be difficult to explain to different teams how best to proceed in a given situation.

What does being a Ukrainian doctor in the USA personally mean to you?

No matter how long you live in the USA, you are an emigrant from somewhere, a representative of your culture. As a Ukrainian, I always show our positive sides and often bring sweets to colleagues to talk about our traditions.

Americans like jokes about people from Eastern Europe. But now the issue of Ukraine is acute for them; they don’t forget about the war and often ask about it. I try to talk a lot about our Face to Face missions, the horrors of the war, and how Russia shells Kyiv, where my family lives.

Along my path, I met Ukrainians who spoke badly about Ukraine. And this always looks terrible. In general, Americans and their culture love positivity. And you will always look much better in the eyes of others if you speak positively about your country, even if you have a different opinion deep inside. This is very important.

What are your plans for the coming years?

Now I am focused on finishing my residency. I’m still thinking about my further path—whether I will go for a subspecialization, and what it will be. The world is very unstable now.

I would like to spend more time in Ukraine, but unfortunately, with residency, it is very difficult. I try to come to Ukraine when I have vacation, at least for a week, to feel life here a little and not fall too far behind it. I don’t want to be a person who doesn’t understand what Ukrainians are living through.

I will maintain my social and volunteer work in Ukraine and hope that the Face to Face missions will continue. Because even if the war ends today, there will be many patients. And they will need help.