Stas Voytenko is from Donetsk. He fell in love with music back in the eighth grade. He learned to play guitar, upgraded old Soviet speakers, and built his first rehearsal space in the summer kitchen of his parents’ house where started a band. After university he had to take a job in the auto industry, but the dream of music never left him. In 2011 he moved to Kyiv and played with different bands, but quickly became disillusioned with show business.

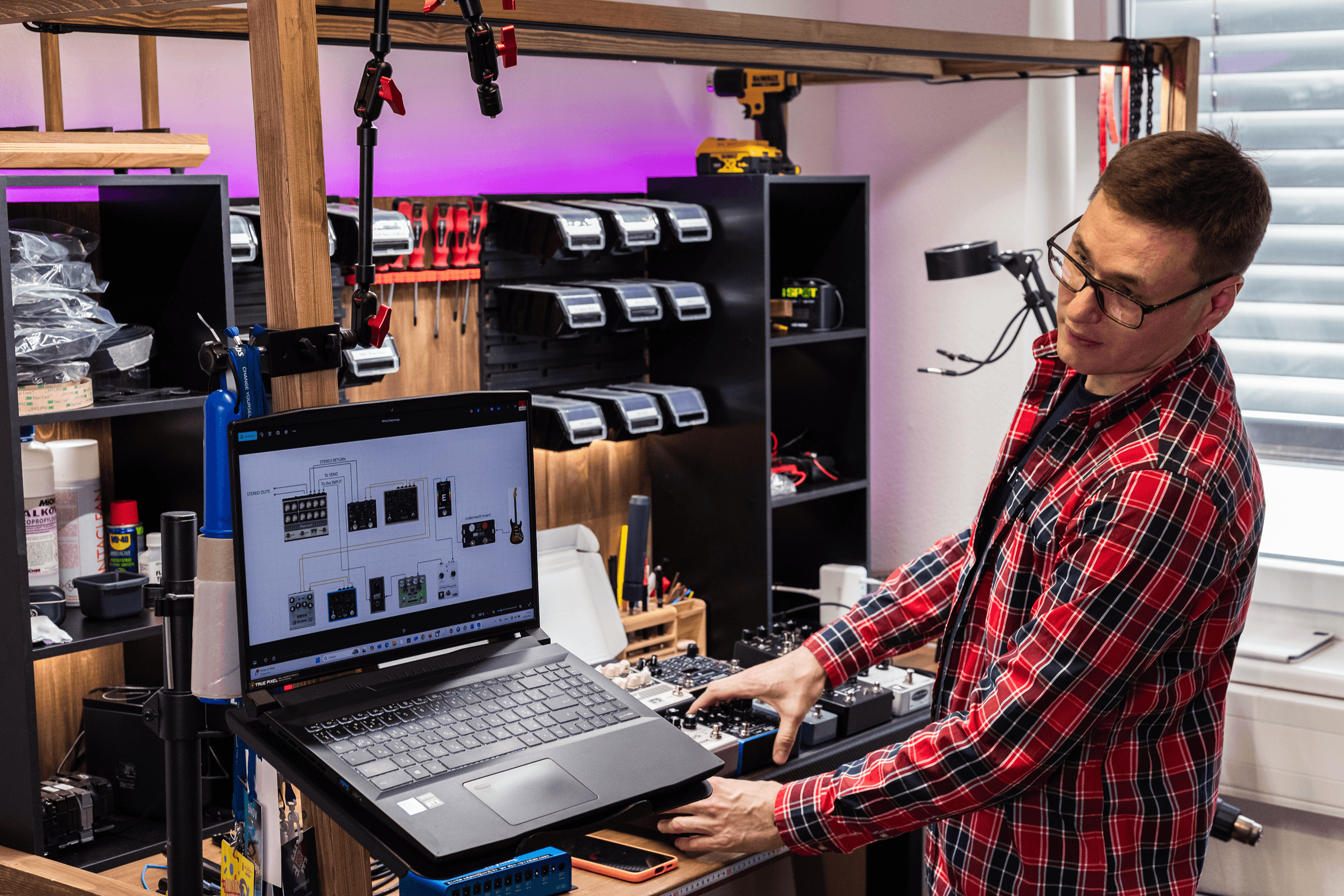

In 2017, he launched WoodyPedalboard, which evolved into the DrStan brand two years later, and became a rig builder — a specialist, as musicians call it, who assembles complete pedalboard setups that change the sound of instruments by adding effects and depth. In 2023, Stas moved to Poland and became famous worldwide.

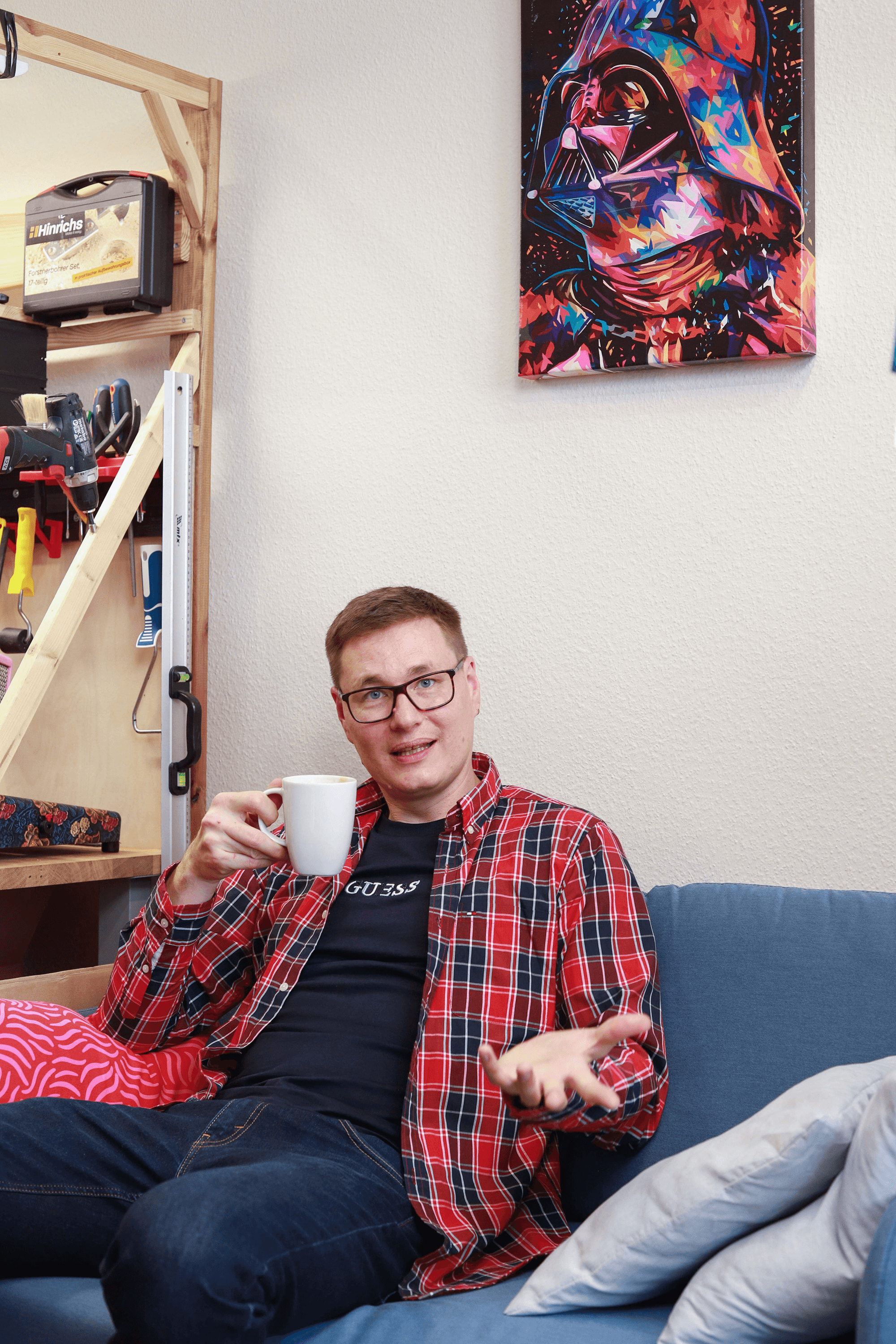

Now based in Austria, he provides boutique services, creating custom pedalboard setups for clients like jazz musicians in New York, the Czech pop group Ewa v Edenu, and even Seal. Without spending a cent on advertising, DrStan has become the second most-followed Instagram account in the pedalboard industry worldwide — and on TikTok, Billie Eilish’s brother messages him. But more than anything, Stas dreams of shining a spotlight on lesser-known yet incredibly skilled makers across the EU and Ukraine who craft top-tier music gear.

How did you become passionate about music?

I first heard the guitar when I was 12. My classmate Serhiy was playing, and I instantly fell in love. I still remember that moment — a wooden object with metal strings, a person doing something with it, and suddenly, magic happened. It was a real “wow” moment, so I asked him to teach me. Besides my classmate, my father’s friends also played guitar romances and gave me notebooks with chords. I spent time in internet cafés, waiting 20 minutes just for a page to load, and bought specialized books. But none of that was really useful until 2011, when I started lessons with a private teacher, Pavlo Sydorenko. He taught me how to serve the song, not just show off that I’m a cool guitarist — which many people in Ukraine do, but I don’t see that in Europe or the States, because the culture is different there.

After my experience in show business, my feelings for the guitar faded, and the romantic side of it disappeared. Plus, after finishing school, I graduated from Donetsk National University of Economics and Trade, tried working in my field, and music was put on hold for a long time.

What kind of work did you do?

In 2007, I sold car accessories for a Donetsk company — things like alarms, car stereos, and security systems. Later, the company’s director passed away, so I started working at my dad’s auto repair shop. There, we basically built vintage cars from scratch, mixing BMWs and Volgas together. I learned how to work with my hands at my dad’s shop. I was the store manager threre at an audio system workshop, but I did everything when needed. Around that time, I got really into subwoofers, built audio systems, and made cables. All in all, I spent seven years in the automotive business.

Why did you decide to move to Kyiv?

One time, I was talking with my best friend Leonid, who was working in Crimea. We were a bit tipsy, and somehow I suggested buying a drum set for when he’d come over. I started looking for drum ads in the newspaper and found some from a music teacher. They delivered the drums disassembled, and we just set them down in the summer kitchen — only to realize we didn’t know how to assemble or play them.

We met the husband of a classmate, told him we had bought drums, and it turned out he was a drummer. That’s how our first band, Farvater, came together, and eventually moved to the capital. On top of that, I was offered a job at a big auto repair shop in Kyiv.

How did you balance working at the auto shop and playing music?

It was tough. I was the assistant head of a department that installed extra audio and security systems. I’d start work at 11 a.m., and by 8 p.m., I’d go straight to band rehearsals until midnight. In between, I tried to write music and lyrics. My management skills helped me book shows and run our social media. My education definitely helped with that too — though at times it got in the way of my creative side.

How did you define success in music back then, and how did you imagine it?

I’d break it into a few stages. Back in Donetsk, we used to rehearse in the summer kitchen, playing songs in the cold with frozen hands. When I moved to Kyiv and visited the legendary Club 44 for the first time, it felt like the highest level. Eventually, we started playing there regularly, and then we wanted more—people singing our songs. And they did. Later, I performed in a stadium with Ukrainian artist Melovin. We were one of the headliners. After that, I started wondering what was next.

Later, the guys and I had our own band called Fireplays. We wrote songs in English, planned tours across Europe, and even found people to help manage it all. But internal disagreements and the COVID pandemic ended my musical adventure.

How did your story with pedalboards begin?

It all started with my love for how sound is created. I was always searching for something new but couldn’t afford to buy it because the economic situation in Ukraine wasn’t the best. For example, in 2007 one pedal in the U.S. cost $100, but in Ukraine it was $120 due to import and customs fees. Meanwhile, the average salary that time in Ukraine was $200 compared to $3,000 in the U.S.

My dad had an awesome engineer working with him who also played guitar and made stuff. He built my first pedal and showed me how to do it, and then I started making them myself. I used textolite boards and ferric chloride on glossy magazine paper — it has to be glossy. Here’s how the process works: you print the circuit tracks on a laser printer, then use an iron to transfer the print onto the board. The ferric chloride eats away the copper on the fiberglass, leaving the tracks under the ink intact. After that, you drill tiny holes to insert and solder different components like transistors, capacitors, operational amplifiers, and diodes, which are used to create guitar effect pedals. That’s how I got into pedals. At first, I made the cases out of wood and covered them with faux leather. I already had a decent number of pedals and was thinking about how to organize them for convenience. That’s how my first pedalboard came about, just a piece of particleboard and some Velcro.

I used to order pedalboards from other people, but I didn’t like the quality, so I had to modify them myself. But pedalboards and pedals always need changing because you’re constantly evolving, searching for new sounds, and new gear comes out that you want to buy. Once, I came across a wooden pedalboard made of mahogany while browsing online. It cost a crazy amount of money for me, and I had to figure out how to get it through eBay since direct shipping to Ukraine didn’t exist back then. So, I found some craftsmen who made wooden pedalboards for me. I put them up for sale on OLX, and people started buying them. That’s how I began making boards not only for myself but also for sale. The name and logo “Doctor Stan” were gifted to me in 2017 by my good friend Ihor Merezhany, an amazing drummer. He said, “I can’t stand looking at that terrible name you made in Times New Roman.”

You mentioned you became disillusioned with show business. Why was that?

The main disappointment was realizing it’s primarily a job — and a tough one at that. I wasn’t afraid of hard work, but for me, music was something higher, it was art. When you work with an artist, you’re just a hired hand: you do exactly what they tell you. And that work doesn’t pay well. Meanwhile, a good guitar costs between $2,000 and $3,000, and a pedalboard can be as much as $10,000. It’s like sports: if you want to stay in shape, you have to train constantly. So you spend your whole life learning, invest a lot of money, and then end up playing music you don’t want to for just $100 or $200.

There are very few people who come into the industry genuinely wanting to create something. When they run into problems, they get discouraged, become bitter, and then it’s really hard to work with them.

For those who don’t know, what exactly is a pedalboard, how are they different, and how much do they cost?

Basically, a pedalboard is just a stand for your pedals. It can be a simple piece of plywood or sturdy plastic where you place your guitar effects. Guitar effects are important for shaping the sound because an electric guitar on its own doesn’t really do much. Most musicians buy guitars that sound good and look nice. That’s why many people choose my boards — they’re functional, beautiful, and made with taste.

As for the cost, you can often find plywood or boards in your attic or basement and cut them to the size you need. So the price can start at zero. The highest price I’ve seen was from an American company that makes wooden pedalboards costing $1,200. But those aren’t meant for touring — they’re just for looking great in a studio, putting pedals on them, and enjoying.

What’s your current price range for pedalboards?

Right now, my smallest board without a bag starts at €245, and the largest with a bag goes up to €400. I’m planning to raise the prices soon because each build takes a lot of time, and production costs are high. Sometimes clients request additional inputs or outputs with custom jacks, which adds to the price — for example, an extra €100.

I also offer a full setup service, where a client sends me their pedals and I handle everything else. Each cable needs to be custom-made, and I connect one pedal to another. That service starts at €1,000, and there’s really no upper limit. On average, clients spend between €1,500 and €2,000.

What is the geography of your orders — where do they come from?

I get inquiries on Instagram from all over the world: Brazil, China, Indonesia, the Emirates, as well as the U.S. and Canada. A lot of clients are from the U.S. because the industry there is huge and well developed.

That’s why, for example, I send just the pedalboards as finished products to clients in the U.S., since until recently, imports under $800 were duty-free there. Each shipment is subject to a 20 percent VAT, which makes it too expensive. That’s why, for clients in the U.S., I usually send just the pedalboards as finished products. Until recently, anything under $800 could be imported duty-free there.

Within the EU, most of my orders come from Germany, the Czech Republic, Italy, and Spain. Sometimes I also get requests from Scandinavia or Finland, where the music industry is strong too.

Are your clients mostly guitarists or singers?

Most of them are guitarists who play electric guitars.

Is there seasonality in your work?

Yes. There’s almost no work from late November to early February. Before the holidays, people are busy with corporate gigs and making money, so they can’t leave their gear for a week or two. In January, many, especially Europeans, take a break. Then the season kicks off — February and March start picking up, and after that, I’m up to my ears.

Is Instagram your main way of communicating with clients?

Yes. I also have a Facebook page with 36,000 followers, but there are some toxic Americans there who call me names. I don’t even bother reading the comments on Facebook anymore.

What tools do you use to promote yourself? Ads, targeting, or is it all word of mouth?

It’s purely organic. I haven’t taken any courses, but from my own experience, I watch what people respond to through Stories and Reels to see what my audience likes. My Instagram grew organically from 5,000 to 66,000 followers.

Which global stars have you worked with?

Seal is my regular client, winner of three Grammy Awards and three Brit Awards. We have become more than just a client and a customer, it’s like a friendship between people who share a love for beauty.

Chris Minh Doky — he’s a really cool guy. I’m also followed by a lot of famous guitarists, like the second guitarist from Guns N' Roses. Once, Billy Eilish’s brother messaged me on TikTok saying, “Dude, make me a pedalboard.” I replied, “Here’s my email, get in touch.” Maybe he expected me to say, “I’ll do it for free,” but I don’t do discounts as a principle. I once heard that Louis Vuitton never gives discounts. I thought, why can’t I be like Louis Vuitton?

Do you mention you’re from Ukraine?

Yes, of course. When I introduce myself, I say I’m originally from Ukraine. But my business is registered in Austria, so I can’t say it’s a Ukrainian brand.

Tell us about your workshop in Austria. Was it difficult to start your business there?

Honestly, it wasn’t too difficult, especially if it’s not your first time dealing with things in Europe like contracts, deposits, and costs. In Poland, for example, you can open a sole proprietorship in an hour, register everywhere, open a business bank account, and operate without a license. As long as it’s not medical work, you usually don’t need much else. In Austria, some professions require licenses. Licenses are required for most things, but some are heavily regulated while others, like mine, are covered by a free trade license. What I do is considered a free trade, so I don’t need a special license for it. However, if you wanted to make or even just tune violins, you’d need a special license. What I do is mostly handmade work. I don’t have any kind of mass production.

A lot of time went into finding the right people. I wanted things to work the same way they did in Poland. There, we had a group chat with a lawyer, an accountant, and a second accountant. You’d ask a question and get an answer right away — everything was perfect. In Austria, it was much harder to find something like that. Then there’s the wait for the license. And then when you try to open a business bank account, they tell you that you need an appointment. You ask how to get one, and they say they don’t know. I spent three days just figuring out how to book an appointment to open a business account.

What’s your opinion of Austria as a country for small businesses?

It’s challenging — not the hardest, but definitely not easy. The taxes are high, and the tax rate is progressive. If your annual income is up to €13,000, you don’t pay income tax. Between €13,000 and €20,000, the tax rate is 20%, up to €40,000 it’s 30%, and eventually it goes as high as 55%. On top of that, there are social contributions like pension and health insurance, which add about 25% of your annual income.

What advice would you give to Ukrainian entrepreneurs who want or plan to start a business in Poland or Austria?

Don’t be afraid, because fear is our biggest enemy. The smarter a person is, the more often they become afraid, because they know a lot and fear many things. When I moved to Austria, I was very scared too. But then I decided to just go with the flow: “The eyes are afraid, but the hands keep working.” You need a bit of healthy risk-taking.

Most importantly, understand how taxes work and why they exist in the country, so you don’t feel bad about paying them. Now in Austria, I know I pay a lot at the end of the year, but I get free dental care in a private clinic because of my health insurance. So, don’t be afraid, pay your taxes, never try to cheat the system — don’t even think about it. And study the country’s laws, because ignorance of the law is no excuse for breaking it.

What are your current ambitions — what would success look like now?

That’s a great question. Right now, being an immigrant, my main goal is just to survive, settle in, and figure out what’s really going on because you still feel a little like an outsider. I don’t have a dream about celebrities, like wanting to build a setup for someone from Metallica, for example. That would probably be good for business, though.

What I really want is to organize my business so I don’t have to be involved in every little thing, to gain freedom. Then I can spend my free time sharing my experience with others. I’ve always been interested in helping those who love creativity. It’s important to me. That’s what I’m doing now — people comment on my work a lot, saying, “This is art.”