A tailored suit, a sharp tie, gleaming polished shoes, and a piercing look behind glasses. The image of 73-year-old Sergei Sviatchenko is just as recognizable as the style of his works. Sviatchenko is one of the world’s most famous collage artists. In his works, he shows fragments of the body, cityscapes, landscapes, and the devastation of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Born into an intellectual family of architects in Kharkiv, he dreamed of a life in art from an early age.

Even as the Soviet Union made its reluctant attempts at change, Sviatchenko pushed boundaries with his collages and abstract paintings, ignoring state censorship. He immigrated to Denmark in the 1990s, where he achieved worldwide fame. But he did not lose his Ukrainian identity. Yellow Blue Business Platform journalist Roksana Rublevska spoke with Sviatchenko to share the story of his extraordinary life.

1.

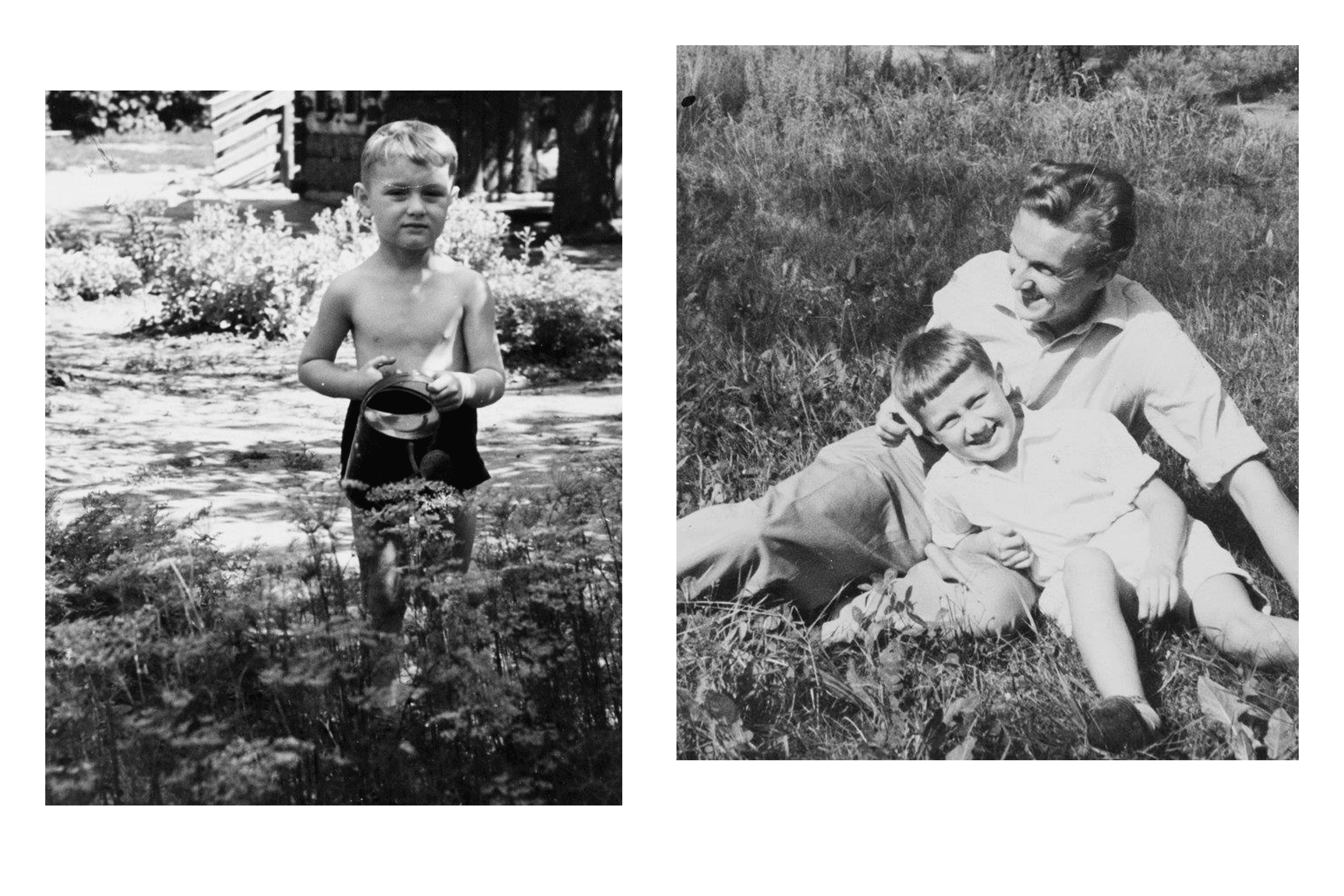

Sergei Sviatchenko spent his early childhood in Kholodna Hora, once a working-class suburb of Kharkiv. After the Second World War, the area became home to engineers, teachers, and recently demobilized soldiers.

The Sviatchenko family lived in his grandmother’s spacious but old house with no basic modern amenities. “Cold entryway, firewood crackling in the stove,” Sergei recalls. “My mother would be cooking, and outside the window was a winter garden that shaped how I saw the world as an artist. I’d dash outside to fetch water half-dressed, shake the snow off the branches, and race back inside.” The family moved out of that little house in the 1960s, when they were allocated a spacious two-room apartment in Pavlove Pole — a neighbourhood that was just being built.

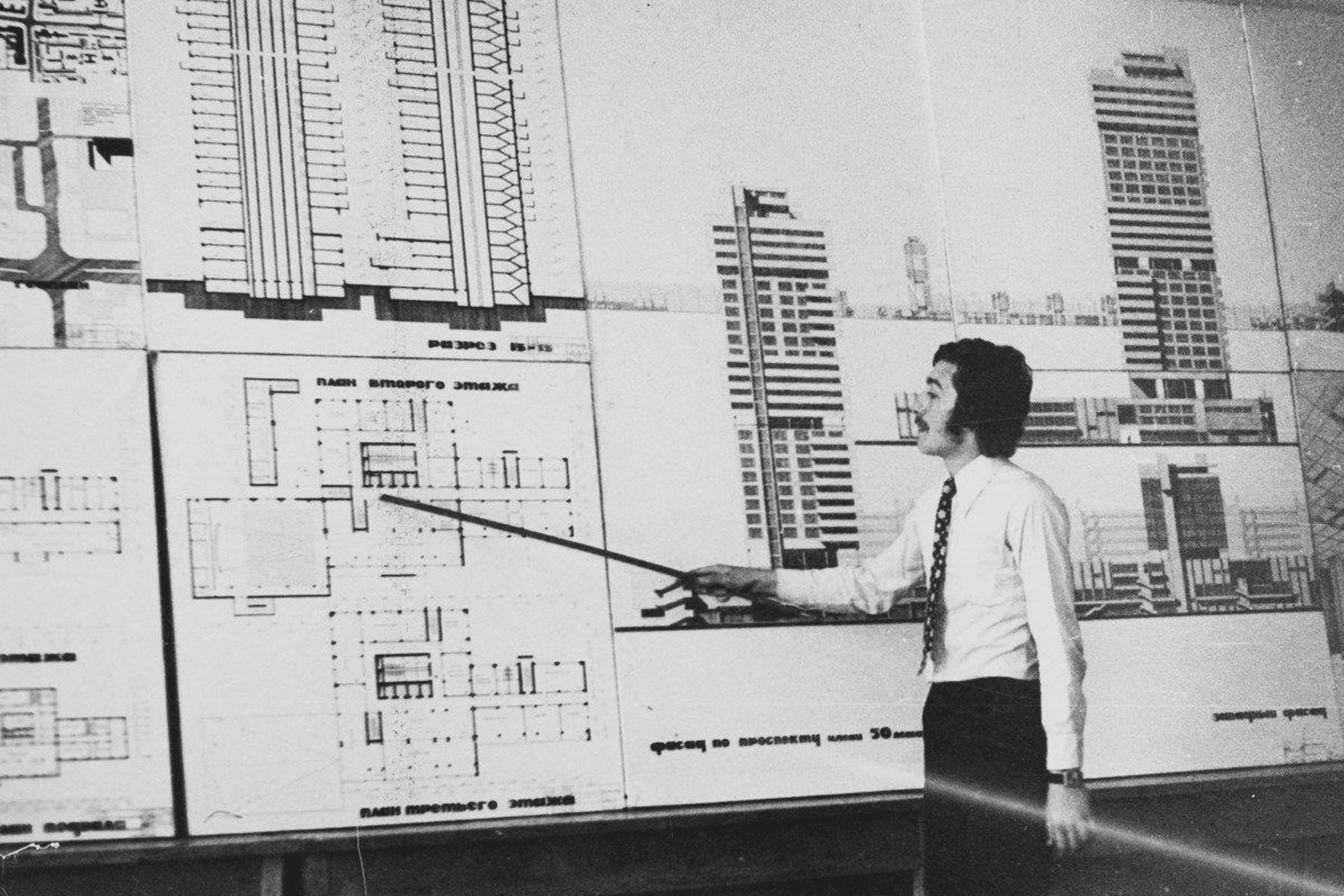

Sergei’s mother, Ninel, had once dreamed of becoming an actress and was even accepted into GITIS, the prestigious theatre institute. Her parents disapproved, and she eventually returned to Kharkiv to study at the Institute of Engineering and Construction. There, she met her future husband, Yevhen Sviatchenko, an architecture student who went on to become one of the city’s well-known architects and later head of the Architecture Department at the Kharkiv Institute of Municipal Construction. From a young age, Sergei observed his father drafting and sketching projects at home. He still jokes that he was born “with a pencil in his hand.”

Sergei Sviatchenko’s father expected him to carry on the family profession. Despite enormous competition, Sergei was accepted into the Architecture Faculty at the Kharkiv Construction Institute. After completing his degree, he was assigned to the Urban Improvement Municipal Architectural Bureau. He designed children’s playgrounds, park arches, and decorative fountains. But he longed for something different. As a teenager, Sergei spent hours studying copies of ‘America’ and ‘England’ magazines he had access to through his father’s connections. For him, they were a portal into a Western world defined by different aesthetics and a different way of thinking. In his room, he painted the walls with images of Steppenwolf’s rock musicians, and their song ‘Born to Be Wild’ would later become his personal statement of independence.

After several years in the bureau, Sergei moved to the Kharkiv Art Institute, joining a newly formed “Exhibition Laboratory” under the USSR Ministry of Education. At just 26, he was appointed its head. He selected student works, organized exhibitions across Ukraine, and essentially served as a curator — a role that long predated the term in Soviet vocabulary.

2.

In 1982, Sergei Sviatchenko went to Kyiv to commence his postgraduate studies at the Kyiv National University of Construction and Architecture. While waiting for a room in the student residence, he stayed temporarily with friends of his parents, the Filatov family. They were people with a Western style of thinking and living. They spoke excellent English and collected jazz records. Their daughter, Olena, was ten years younger than Sergei, and the two quickly became drawn to each other. They married two years later.

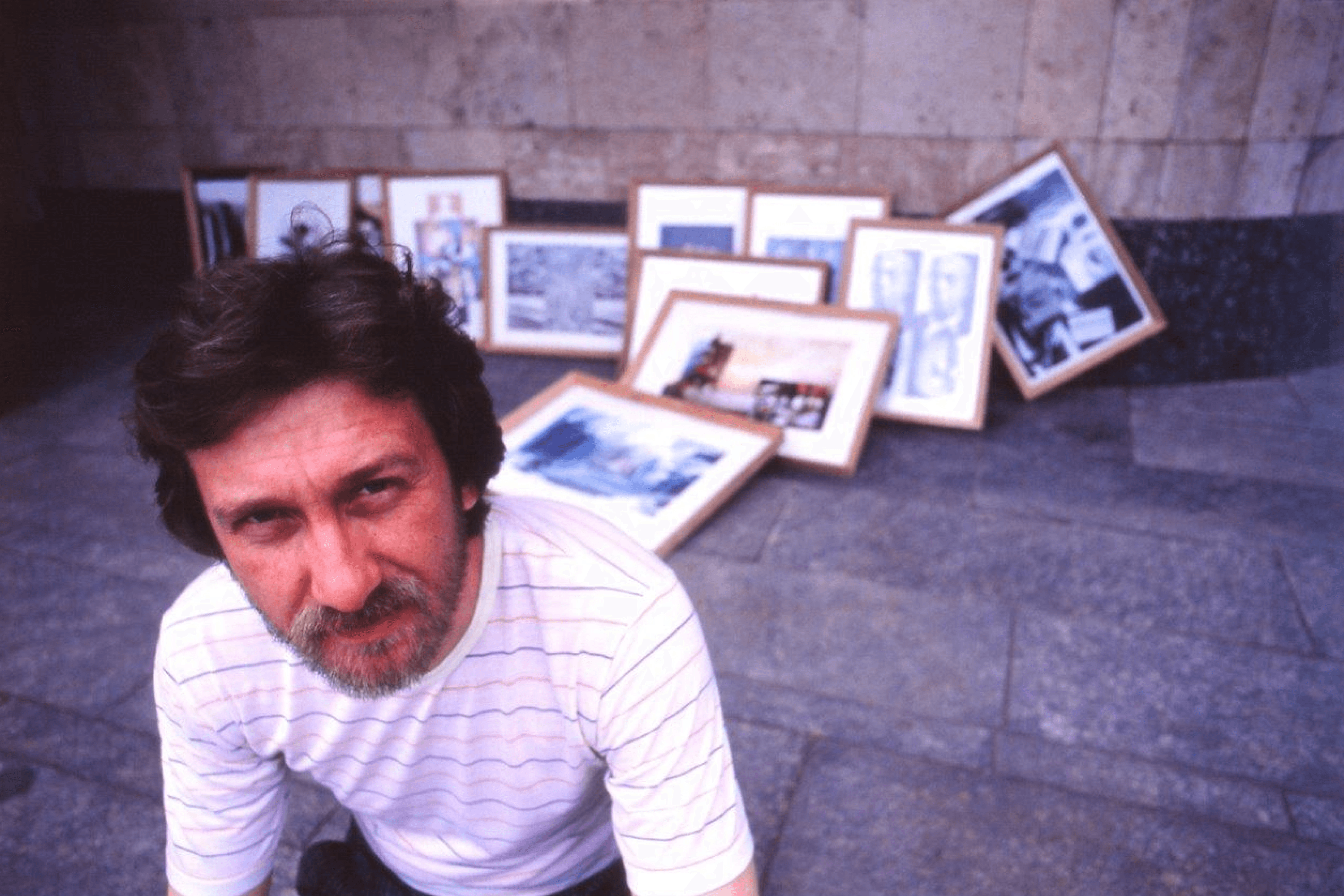

By then, Perestroika had already begun in the USSR, and artists were gaining more artistic freedom for self-expression. Starting in 1985, Sviatchenko began creating collages, and a few times each year he and Olena would sell them along Kyiv’s Andriivskyi Descent. One day, a man approached him and said, “Your work is remarkable. I’m the editor-in-chief of a youth magazine, Ranok. Would you be interested in becoming our art director?”

This is how Sergei Sviatchenko remembers meeting Oleksandr Rushchak — the editor searching for someone capable of reinventing a tired Soviet-era magazine. At first, Sergei even thought it might be a prank. But Rushchak was serious and allowed him to create a new layout for the magazine using his collages, without looking over his shoulder or worrying about censorship. Sviatchenko was offered the promised position of picture editor, and he found himself facing a major decision. He phoned his father for advice: should he finish his academic work and return to Kharkiv to teach, or take the leap and pursue this new, uncertain path?

His father, a lifelong advocate of architecture, surprised him with a clear, decisive answer: “Move toward art. I see tremendous potential in you.”

Sviatchenko found himself in the editorial office, where he showed a layout of what a contemporary publication could look like. He worked as art director, designer, and curator all at once — creating collages, designing covers, painting, and organizing exhibitions. From his magazine’s Kyiv studio, he produced avant-garde issues that stood out sharply from the official Soviet press.

At some point, Sergei came up with the idea of featuring young artists who thought in a modern, forward-looking way, publishing their works on the magazine’s pages and introducing them to readers. “I had a press badge,” he recalls. “I could walk into any creative space and decide what to showcase and who to highlight. And then I thought: why not elevate the contemporary Ukrainian art of the ‘New Wave’? That’s when we in the editorial office decided to start organizing exhibitions.”

In 1987, Sergei Sviatchenko organized and curated what became the first contemporary art exhibition in Kyiv with Ranok magazine and the Estonian publication Norus. The show took place at the Polytechnic Institute as part of Youth Crossroads, a project launched by entrepreneur Viktor Khamatov, a young cooperative owner, art lover, and entrepreneur, at the Kvant factory. After a second collaborative exhibition featuring young Ukrainian and Lithuanian artists (supported by Ranok and Nemunus), Sviatchenko proposed establishing the first Centre for Contemporary Art in the Soviet Union — Soviar. He developed its manifesto, logo, and platform, becoming its first art director and curator, while Khamatov served as president, overseeing project execution.

This marked the start of their international work together, organizing exhibitions of contemporary Ukrainian art abroad, including in the United States and Denmark.

3.

Their first major event was the very first Soviet–American exhibition Creating the World of Art Together, staged in 1988 by Global Concept and the Soviart Centre. It drew unprecedented crowds in Kyiv, capturing the spirit of optimism and freedom that accompanied Gorbachev’s glasnost. A year later, the project 21 Views: Young Contemporary Ukrainian Artists introduced Ukrainian art to Denmark, followed in 1990 by Ukrainian Art-ART (the 60s–80s), which opened in Kyiv, Odense, and Copenhagen. At that exhibition, Sviatchenko presented Joy Behind the Mountains, which was acquired by the Odense municipality and earned him a scholarship and residency. Meanwhile, Soviart continued an active exhibition program across Kyiv, Kharkiv, Tallinn, Riga, and other cities.

It was his first time in Denmark, and he fell in love with it. “I understood right away that this was a place where I could breathe freely,” he says. So when the Odense municipality offered him a three-month, fully funded creative residency, he didn’t hesitate for long. He left his positions at Soviart and Ranok and leapt into uncertainty. On October 6, 1990, Sviatchenko arrived in Herning carrying a single suitcase and a roll of canvases. “I knew fewer than fifty English words, but that didn’t stop me,” he recalls. “The next day, I sat alone in the studio with a bottle of Coca-Cola, happily celebrating my 38th birthday.”

Working in a spacious studio above the local art school, Sviatchenko had to prove he was worthy of the residency he’d been granted. He spent his days creating new paintings, putting collage work aside for a while as he explored abstraction. A month later, his wife Olena arrived in Denmark with their two-year-old son, Philip. Their visa was about to expire — but just then, Sviatchenko received an invitation to teach watercolour and collage at another residency, this time in the Danish city of Viborg. The family moved there for what was meant to be a three-month stay, but it ultimately became their permanent home. Erik Johannesen, the NordArt gallerist, fell in love with Sviatchenko’s work and organized a solo exhibition for him. It turned into a sensation — every painting sold within two days. Johannesen offered him a professional contract along with a share of the sales. Just three years later, in 1994, Sviatchenko found himself standing on the steps of Paris’s Grand Palais, catalogue in hand, unveiling a new solo show at FIAC — one of the world’s premier contemporary art fairs.

His works were soon featured at another newly opened gallery, Igelund in Copenhagen, where he was introduced thanks to Johannesen’s continued support.

Danish society, though formally hospitable, set a steep path to integration for anyone not born in the country. “Danes tend to be very private,” Sviatchenko explains. “They smile at you, they buy your paintings, but communication ends there. They’re not particularly interested in your personal life or your challenges, and they rarely build deep relationships with foreigners. But I was fortunate — they were genuinely interested in my art, and through my paintings, they came to understand our Ukrainian family. My education and upbringing were key to building new friendships.”

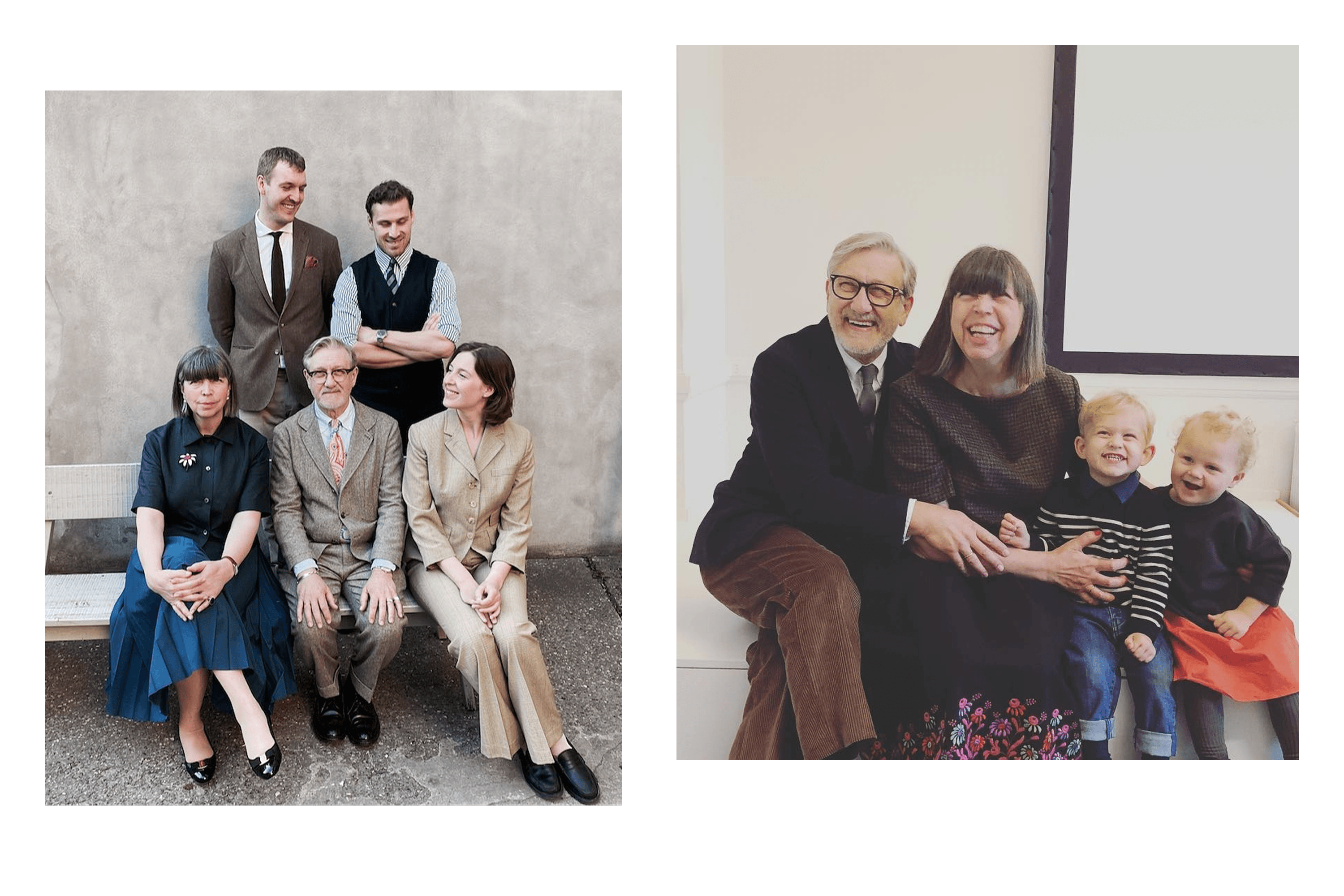

Sviatchenko soon began exhibiting in Copenhagen, Amsterdam, Stockholm, Brussels, and Paris, where his works sold consistently. By then, in 1991, he and Olena had welcomed twins, Erik and Oleksandra. Olena stayed home with the children and couldn’t work, making Sergei the family’s sole provider. “We entered Danish middle-class life right away,” he says. “Not lavishly, but comfortably and with dignity. My art allowed me to fully support my family.”

The first buyers of Sviatchenko’s works were doctors, teachers, and entrepreneurs. They did not know who he was, but they sensed something distinct in his work. Sergei soon built a small circle of people who understood his art, but still did not understand the artist himself, despite his now-fluent English. He built the image of openness, integrity, and professionalism: a hardworking artist who asked for nothing more than the chance to create and contribute to the country that had welcomed him. Over time, his paintings appeared in two galleries: one he approached himself, and the other, through Erik’s help.

Sergei and Olena shared responsibilities at home: while one looked after their three children, the other attended Danish language classes. Sergei recalls that he naturally combined art and fatherhood — painting with the children nearby, taking them to exhibitions and discussing what they saw, reading books to them out loud. “Today, my oldest son Philip passes the same values on to his own kids. He visits the same places, the same museums. And I realize he’s continuing a part of me. It means I must have done something right back then.”

In 1993, Sergei Sviatchenko was granted official permission to live and work in Denmark in recognition of his cultural contribution, and seven years later, he became a Danish citizen. He did not return to Ukraine. When asked why, he explains that he wanted to build his artistic career in the West first. Sviatchenko felt he needed to establish solid roots there before bringing his unique artistic experience back to Ukraine — “if they ever asked,” he says. It took 27 years before the invitation finally came.

4.

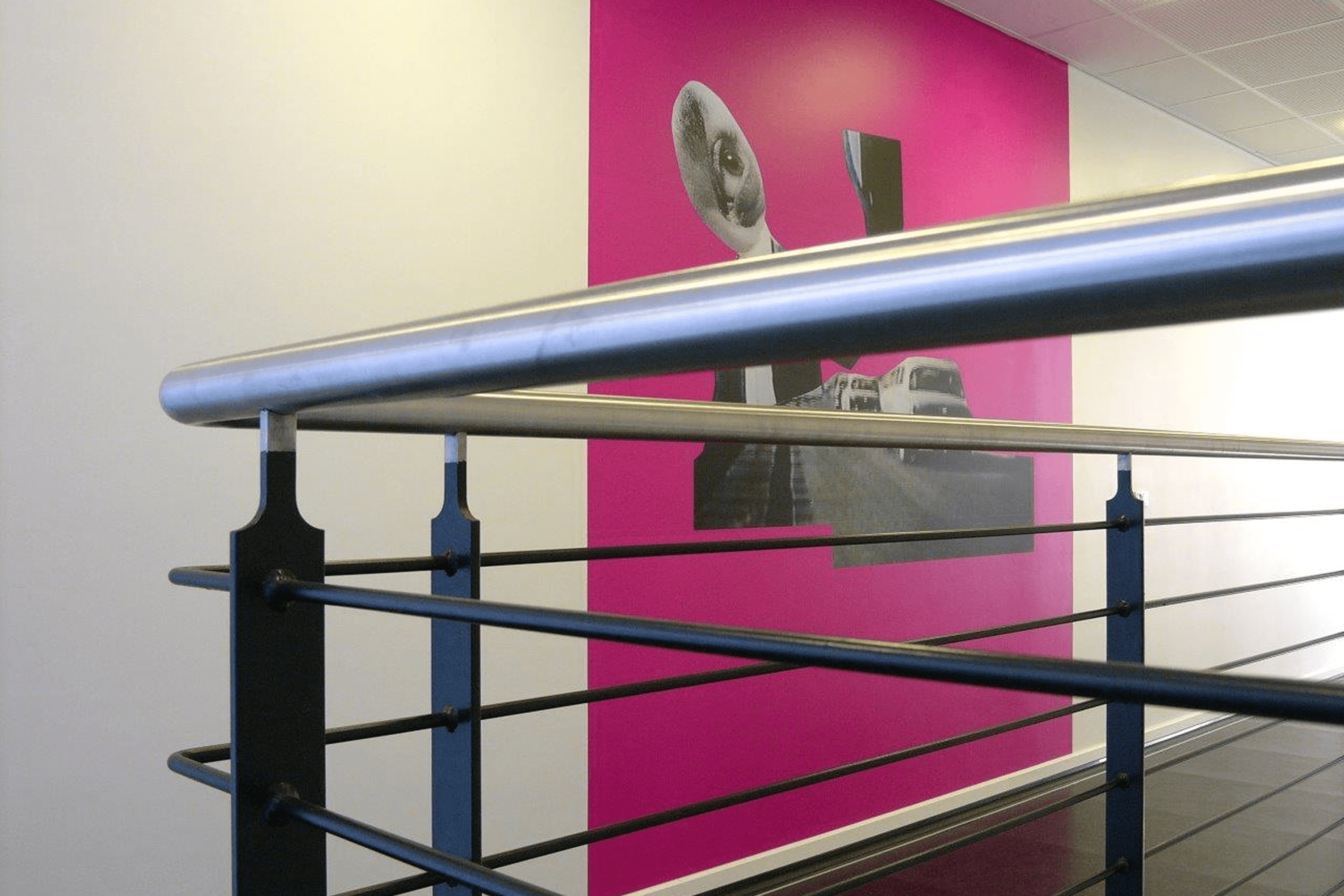

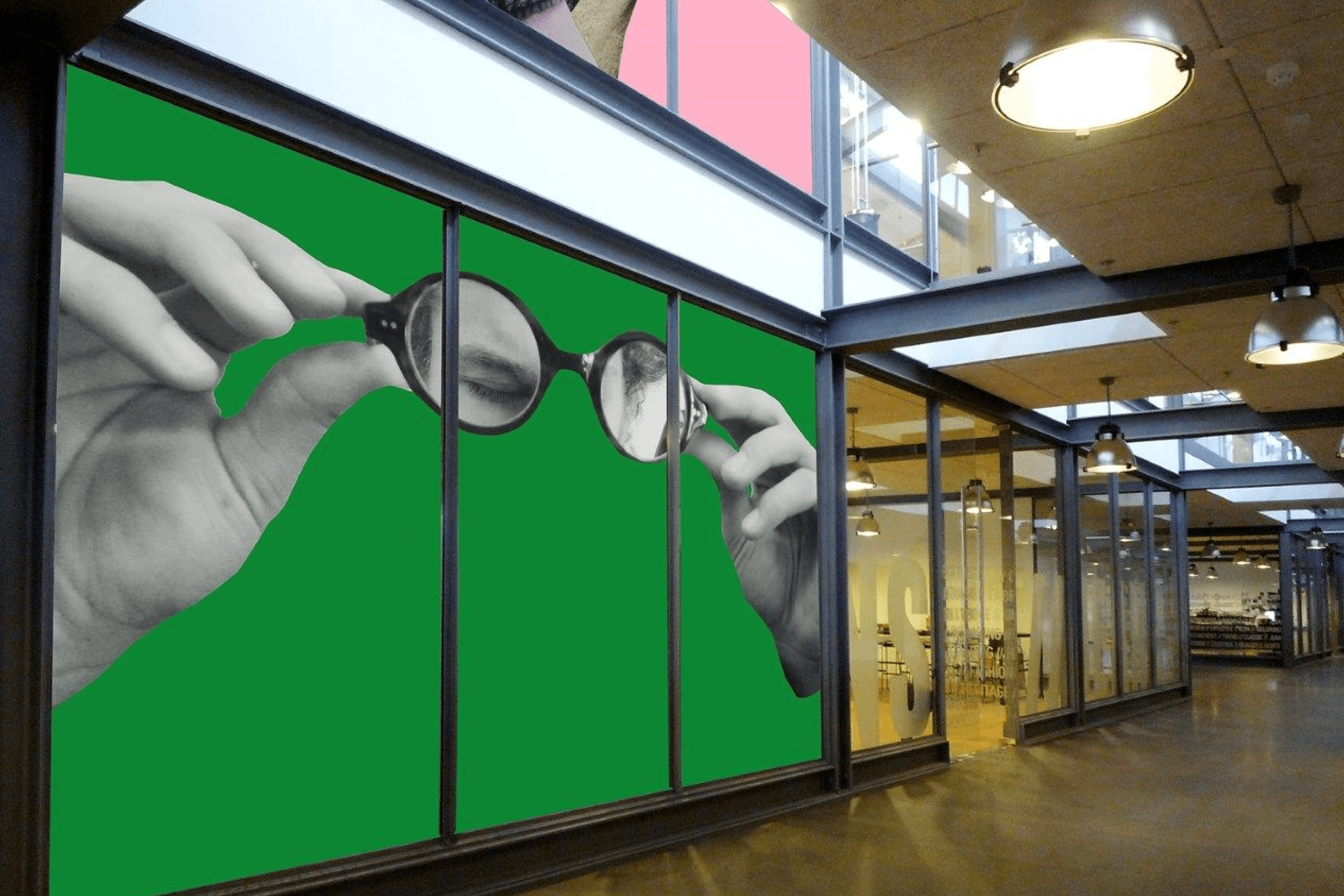

After his first years of work in Denmark, Sergei Sviatchenko began receiving commissions from the business community. In 1998, he was hired for a project at Nokia’s Copenhagen complex. “The architect asked me to create large abstract pieces for the stairwell leading up to the 14th floor,” he recalls. “These were massive chipboard-based works, and I completed them in a dedicated studio. At the same time, I was caring for our son Philip to make things a bit easier for Olena, who was home with the twins. For Philip and me, those were some wonderful days together.”

Denmark has one of the highest art taxes in Europe — 38-70%. As Sviatchenko explains, it is a country with a small population and a limited number of collectors, so demand for art is lower than in France, Germany, or the UK. Private collectors are relatively rare as well, since Danes generally don’t buy expensive items to highlight their status. That makes it difficult for artists to set high prices. For him, corporations became the solution. They offered the chance to take on ambitious projects and maintain a stable, comfortable life for their large family.

In 2001, Sergei Sviatchenko received a major commission from the country’s largest bank, Jyske Bank. The bank was constructing a new complex in Silkeborg, and the architectural firm invited him to create a large-scale artwork for the space. He needed to develop a monumental artwork covering 150 m² across two floors of a central stairwell. This wall piece became one of the largest ones in office buildings in Europe. Sviatchenko dedicated it to nature, focusing on the relationship between light and space and capturing the atmosphere of a sunset that complemented the surrounding forest and lake.

This wall installation, Illumination of Vertical and Horizontal Connections, became one of the largest paintings ever created for an office space in Europe. Sviatchenko dedicated the piece to nature and to the interplay of light and space, aiming to capture the atmosphere of a sunset that blended seamlessly with the forest and lake surrounding the building.

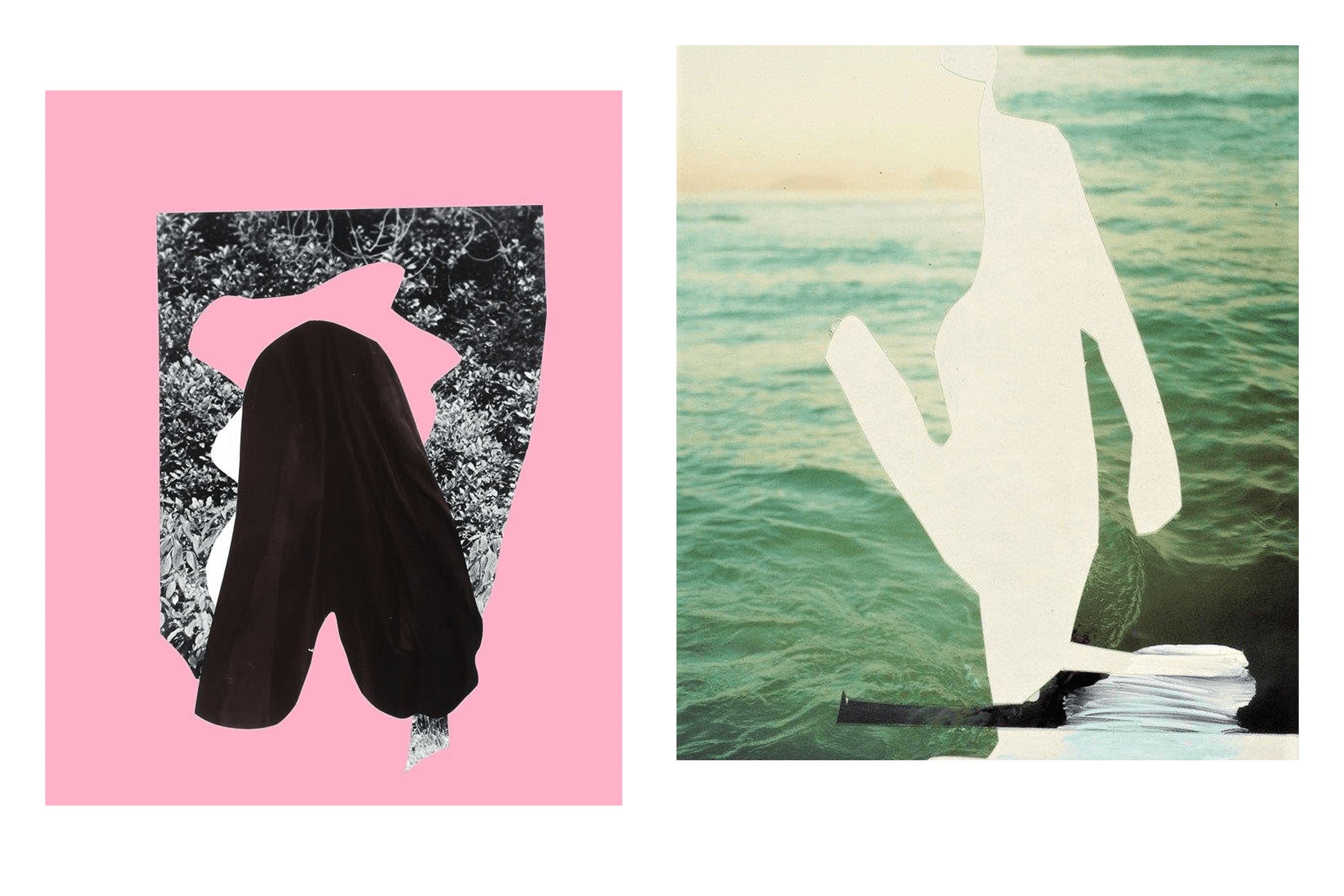

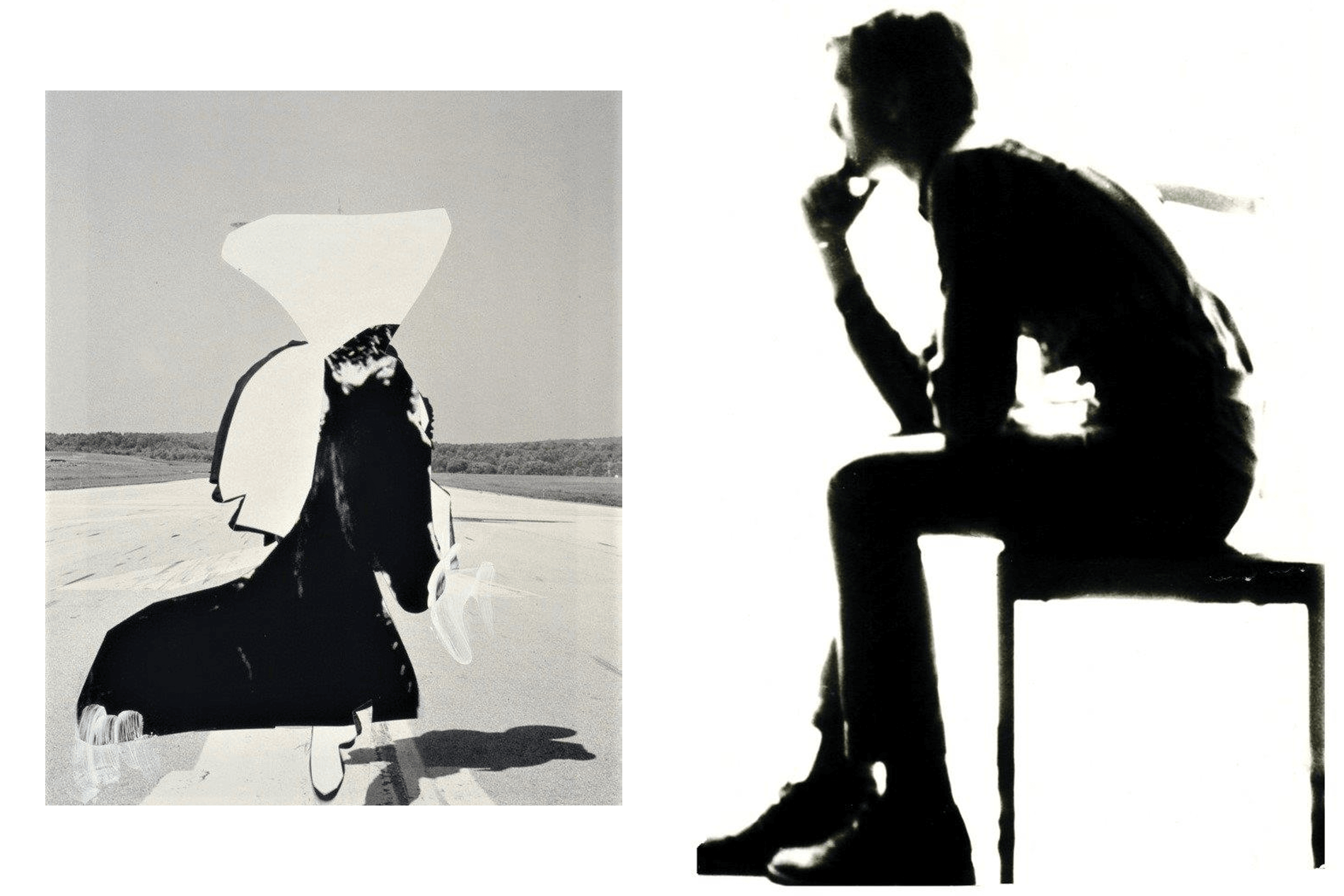

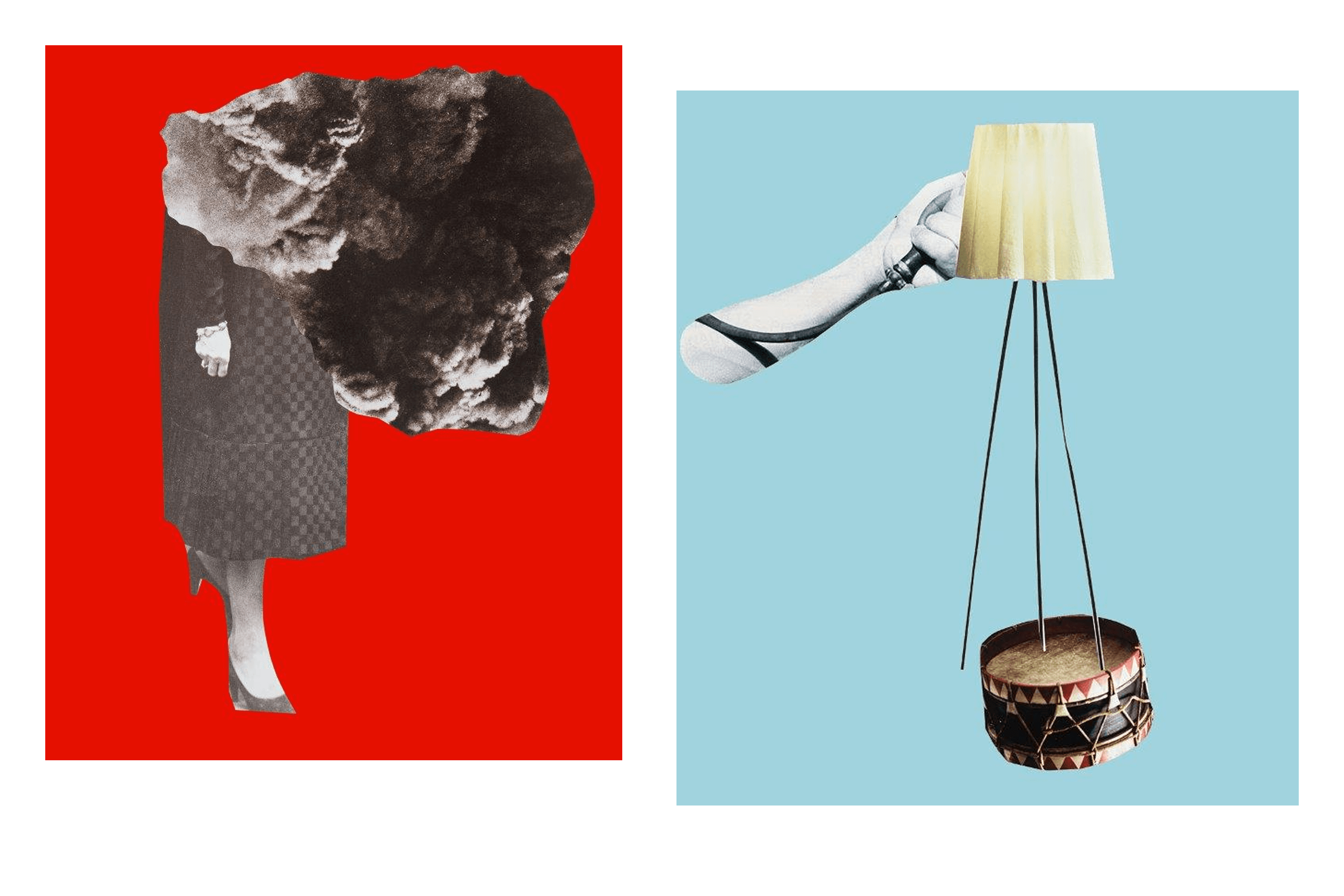

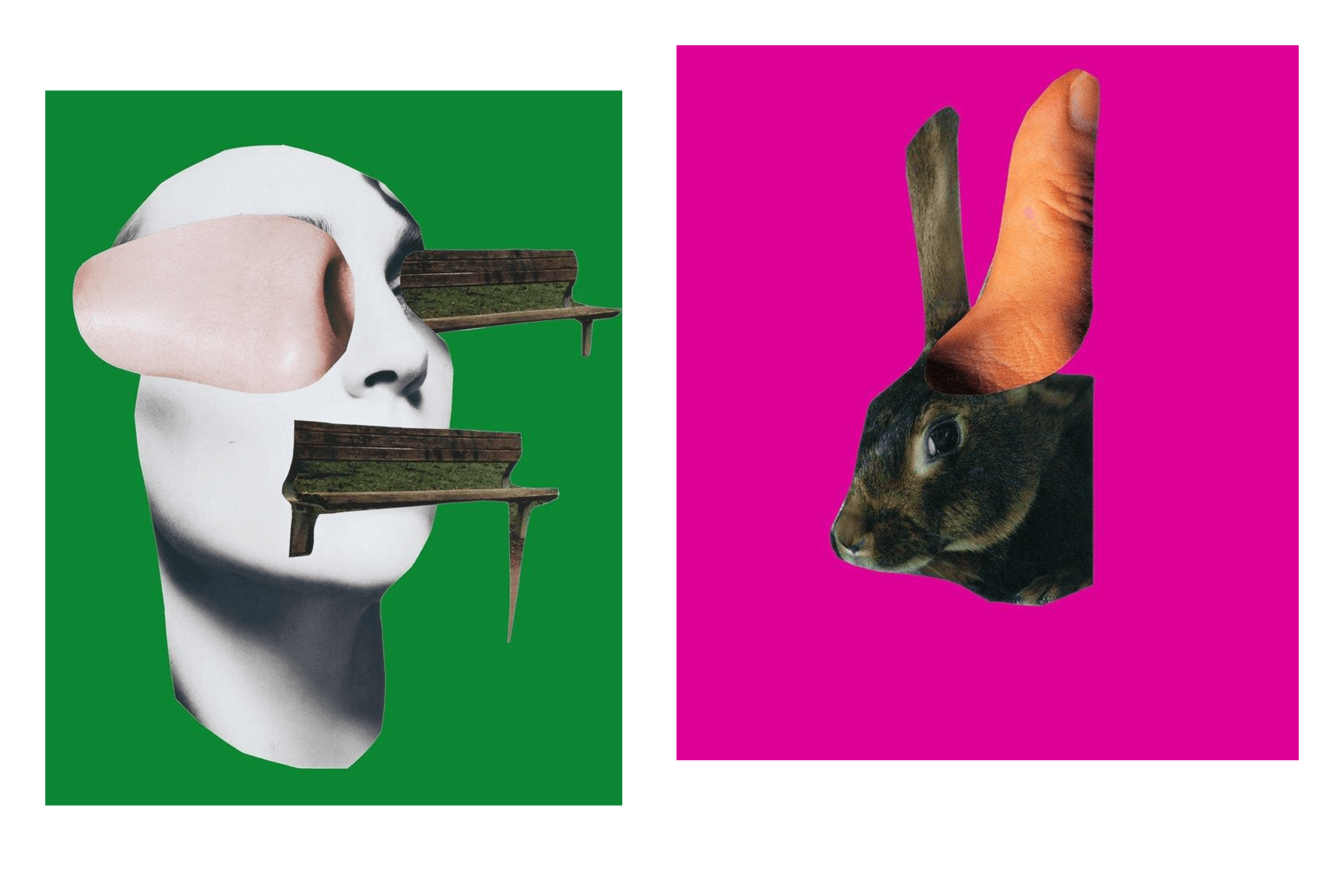

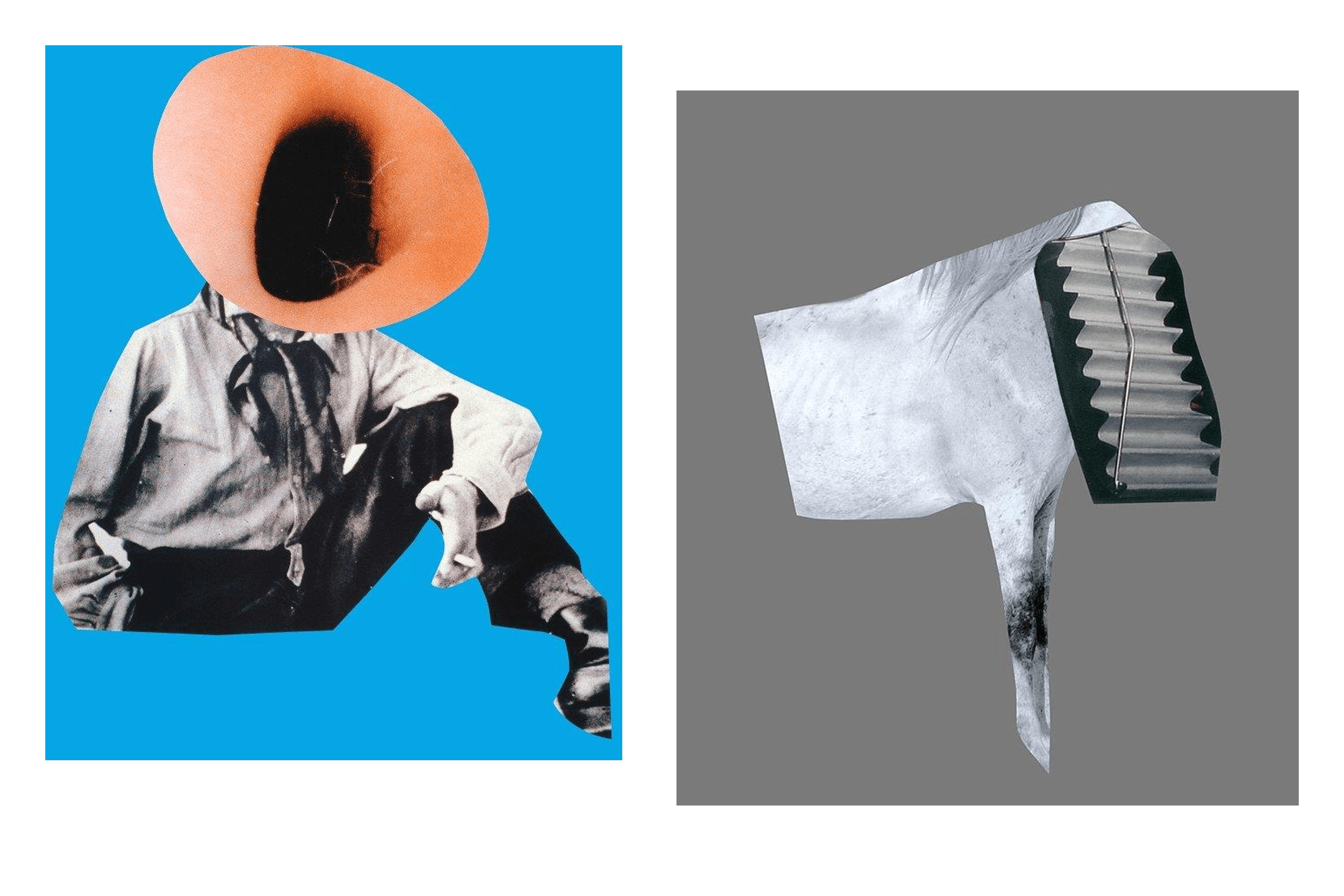

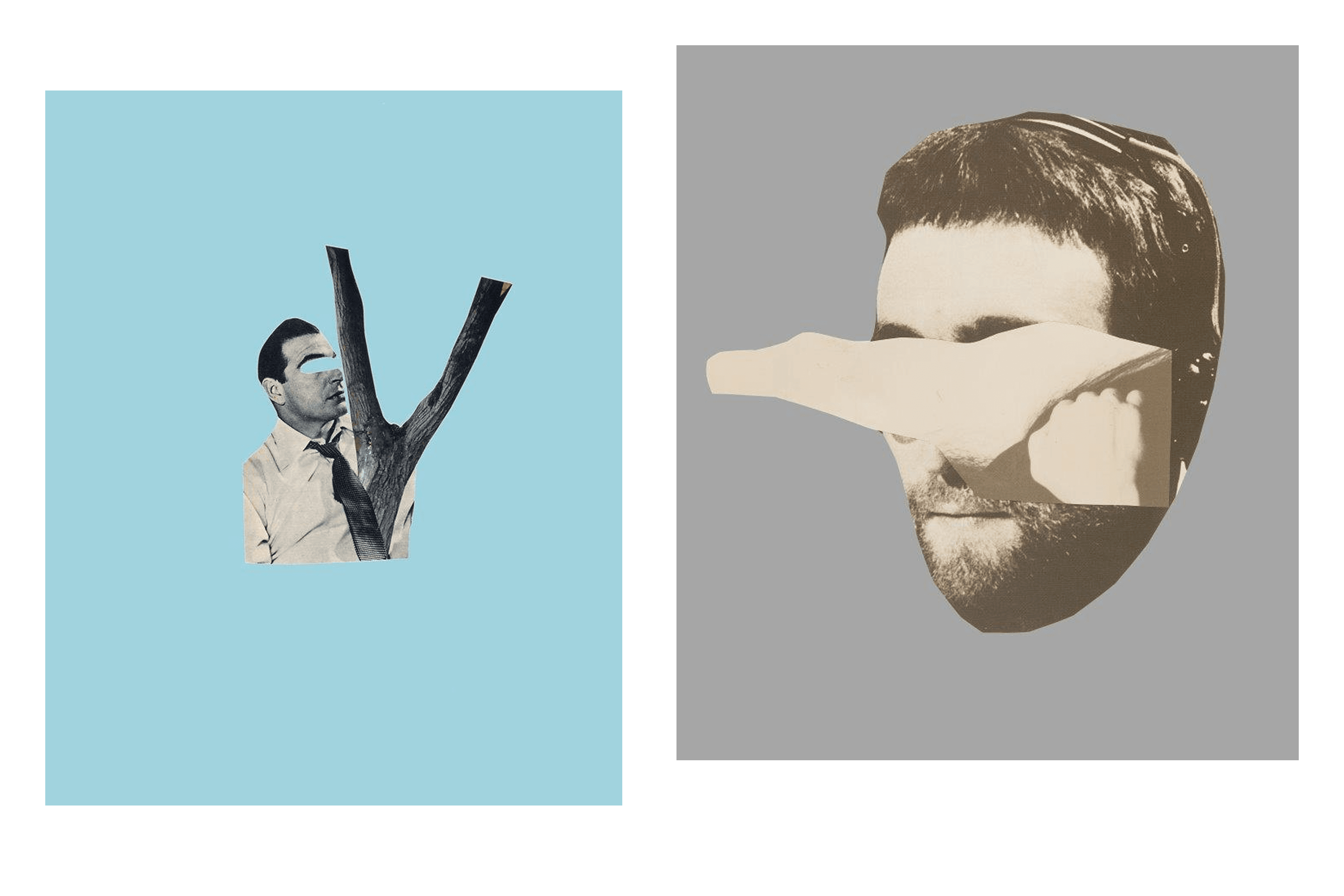

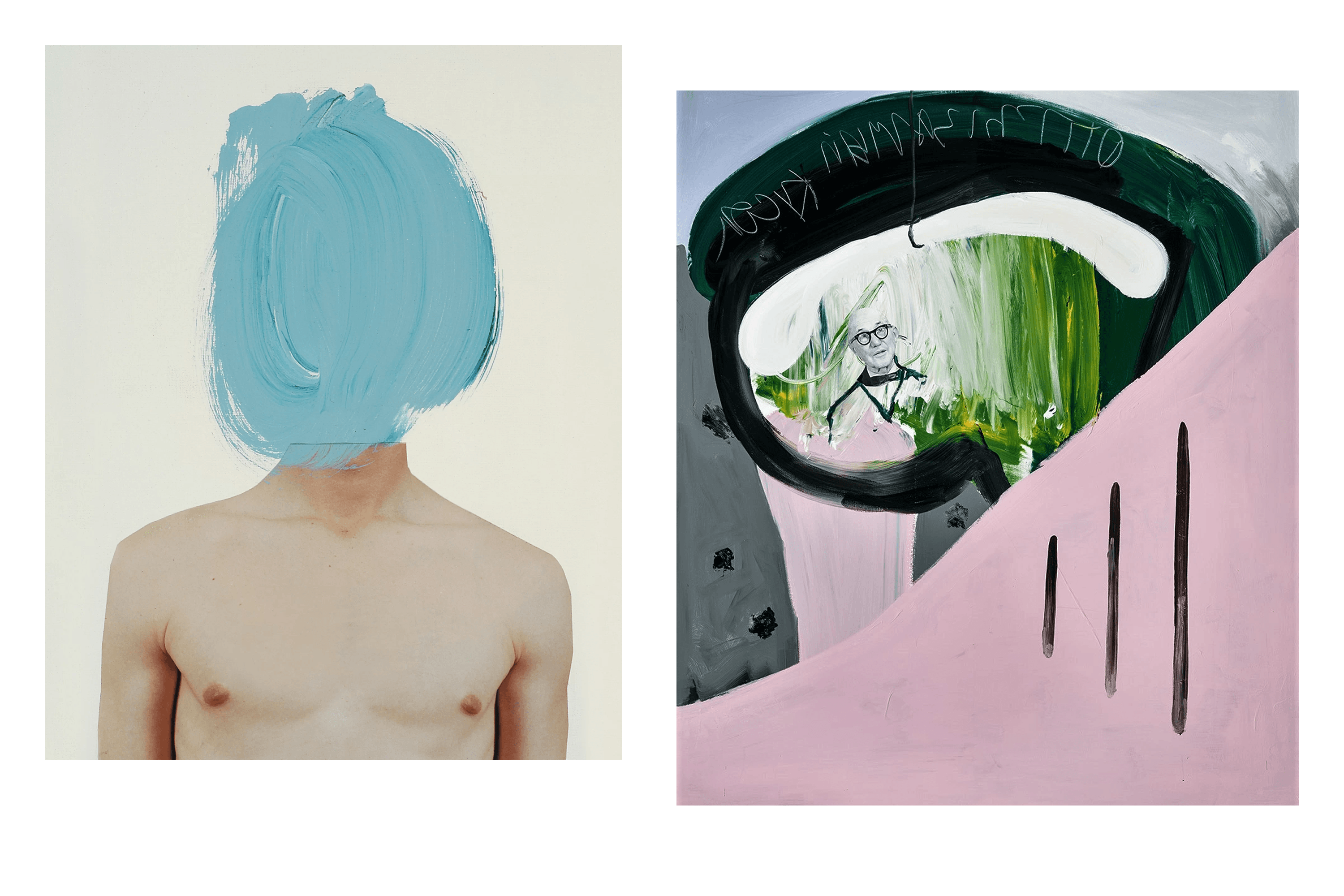

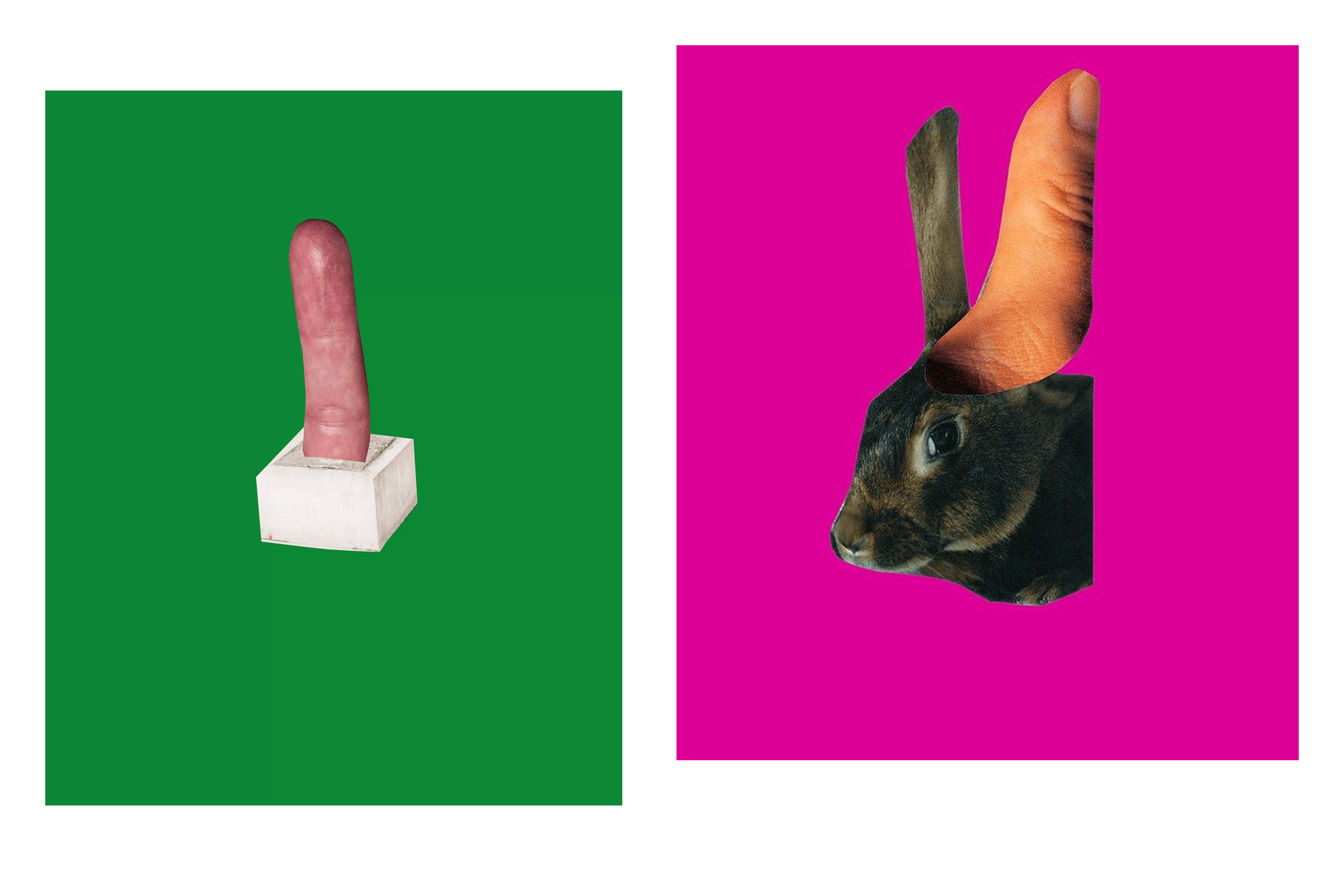

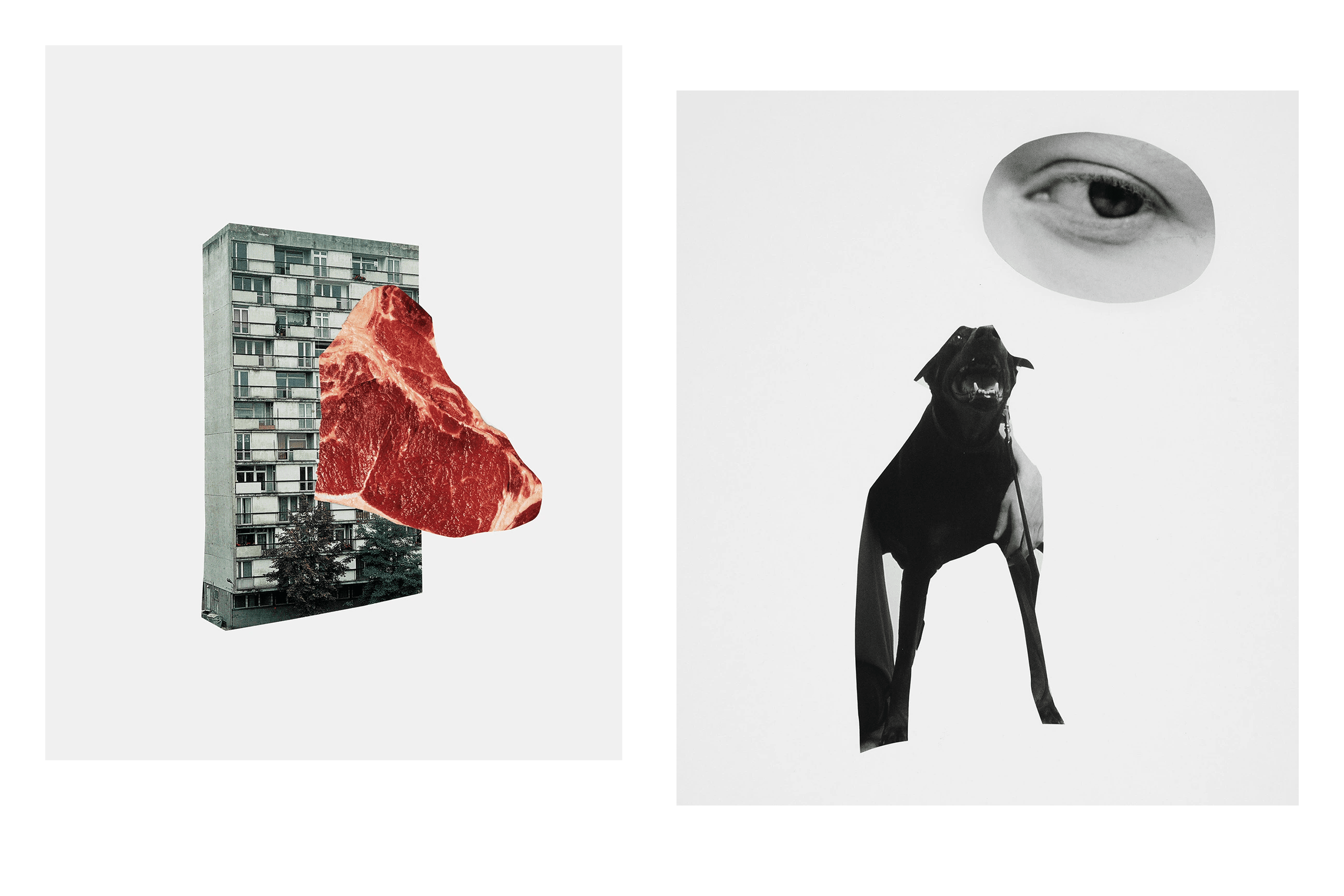

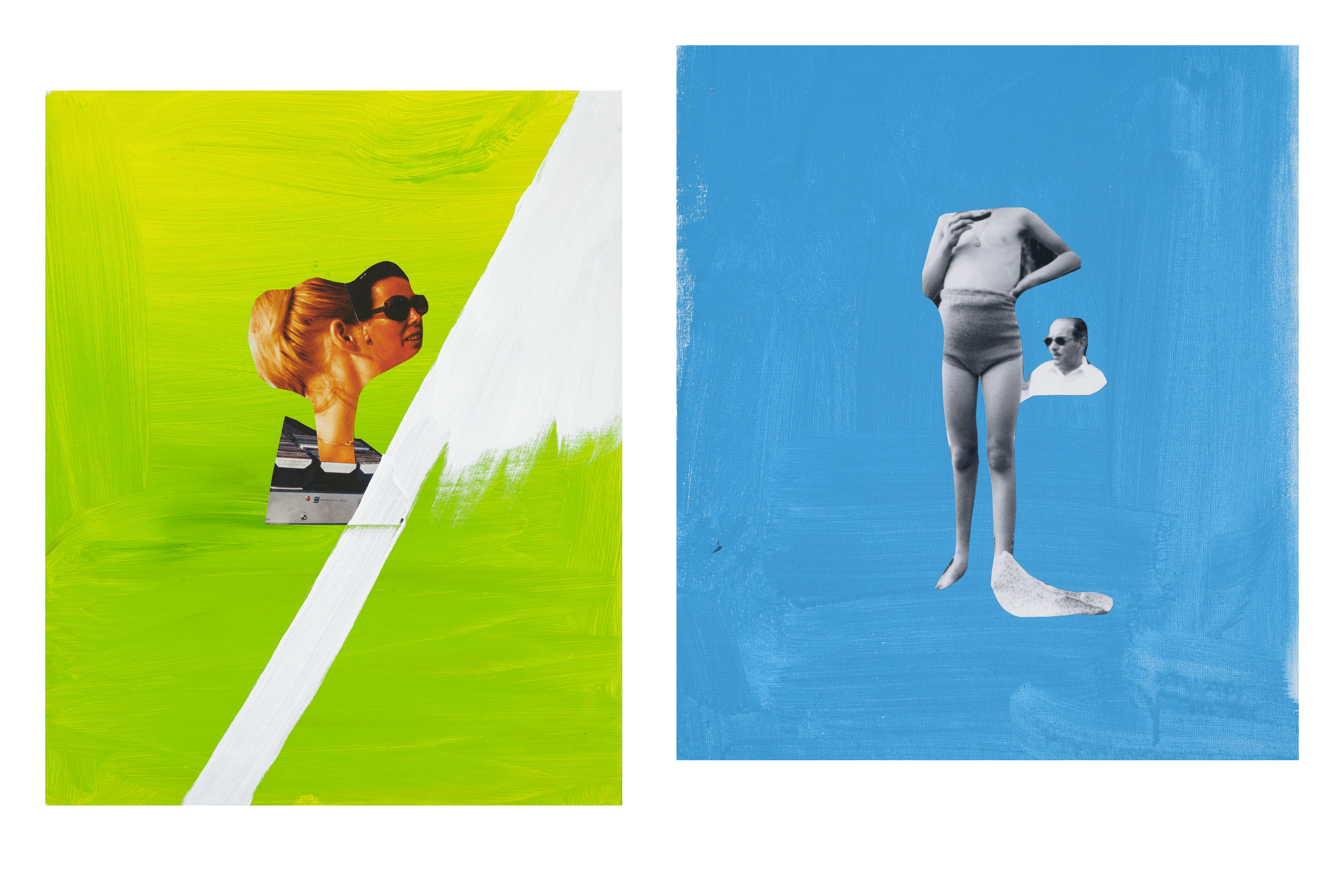

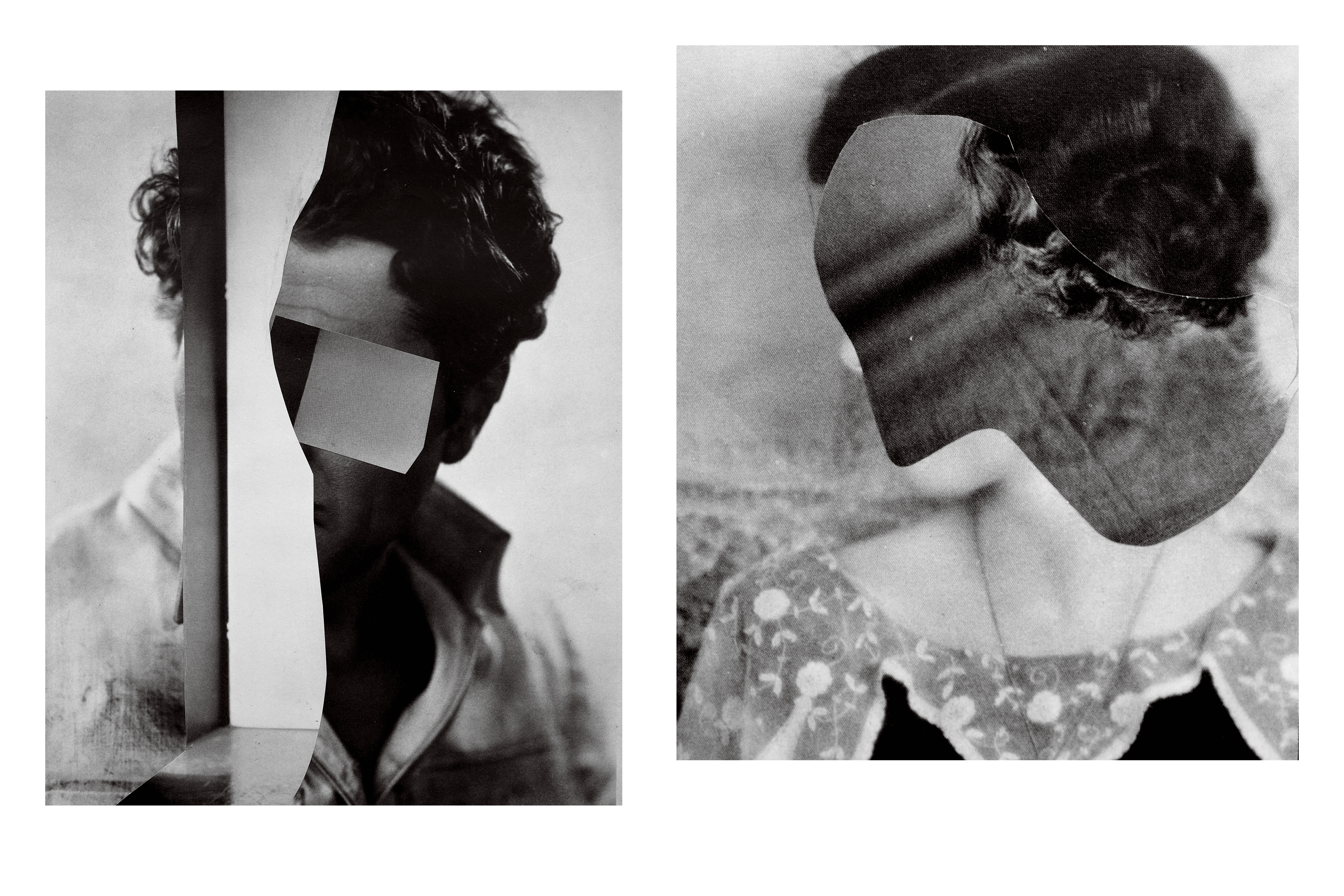

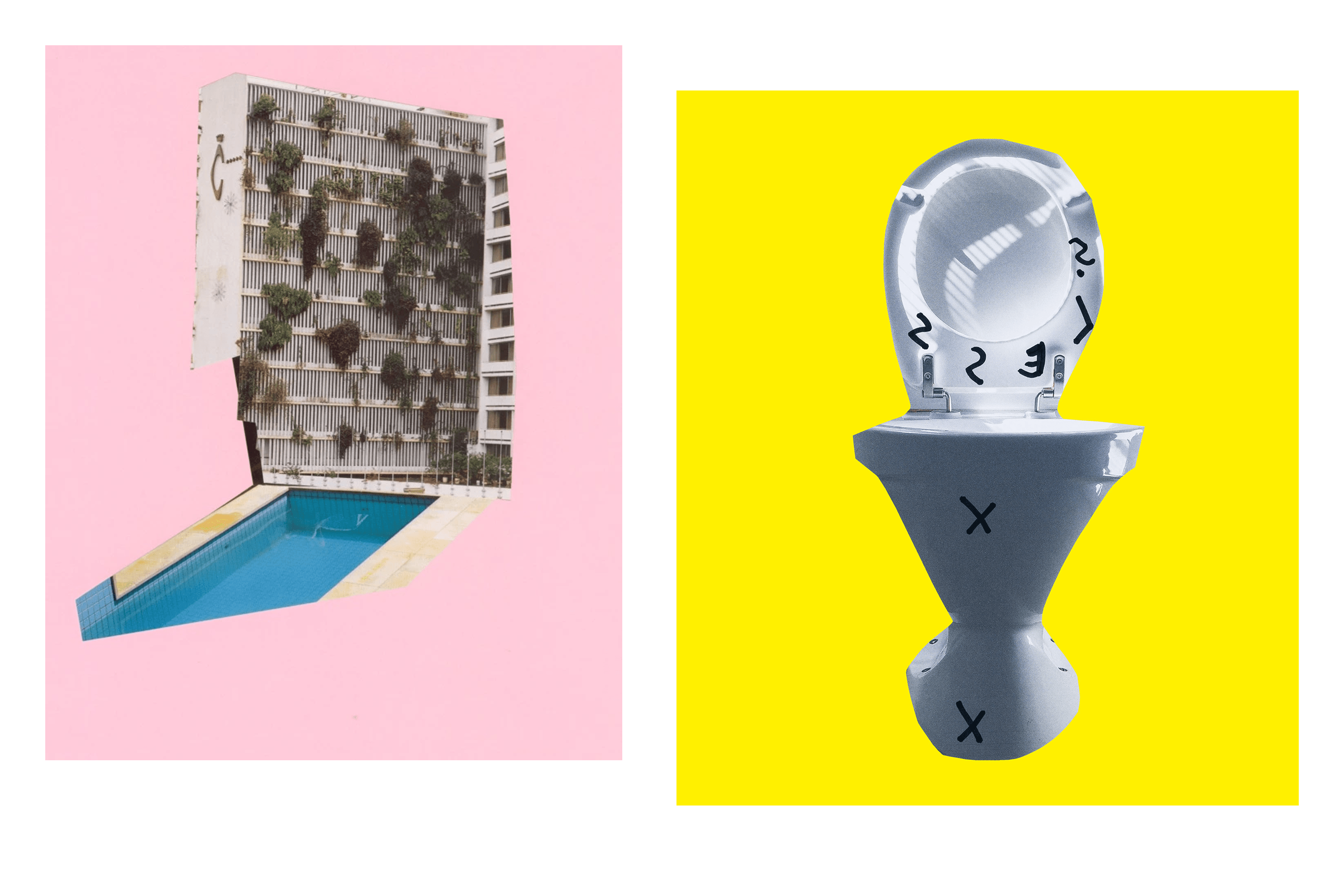

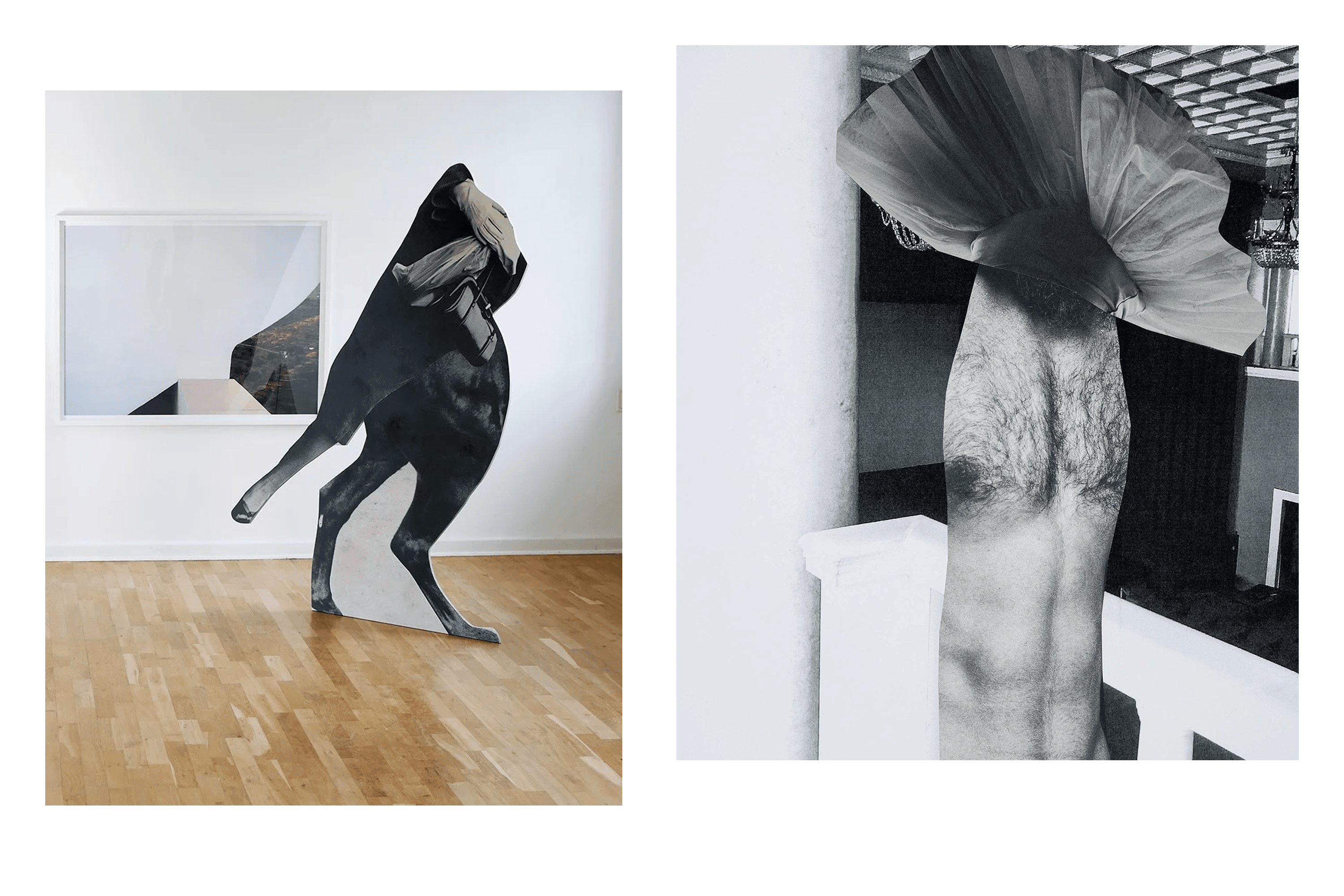

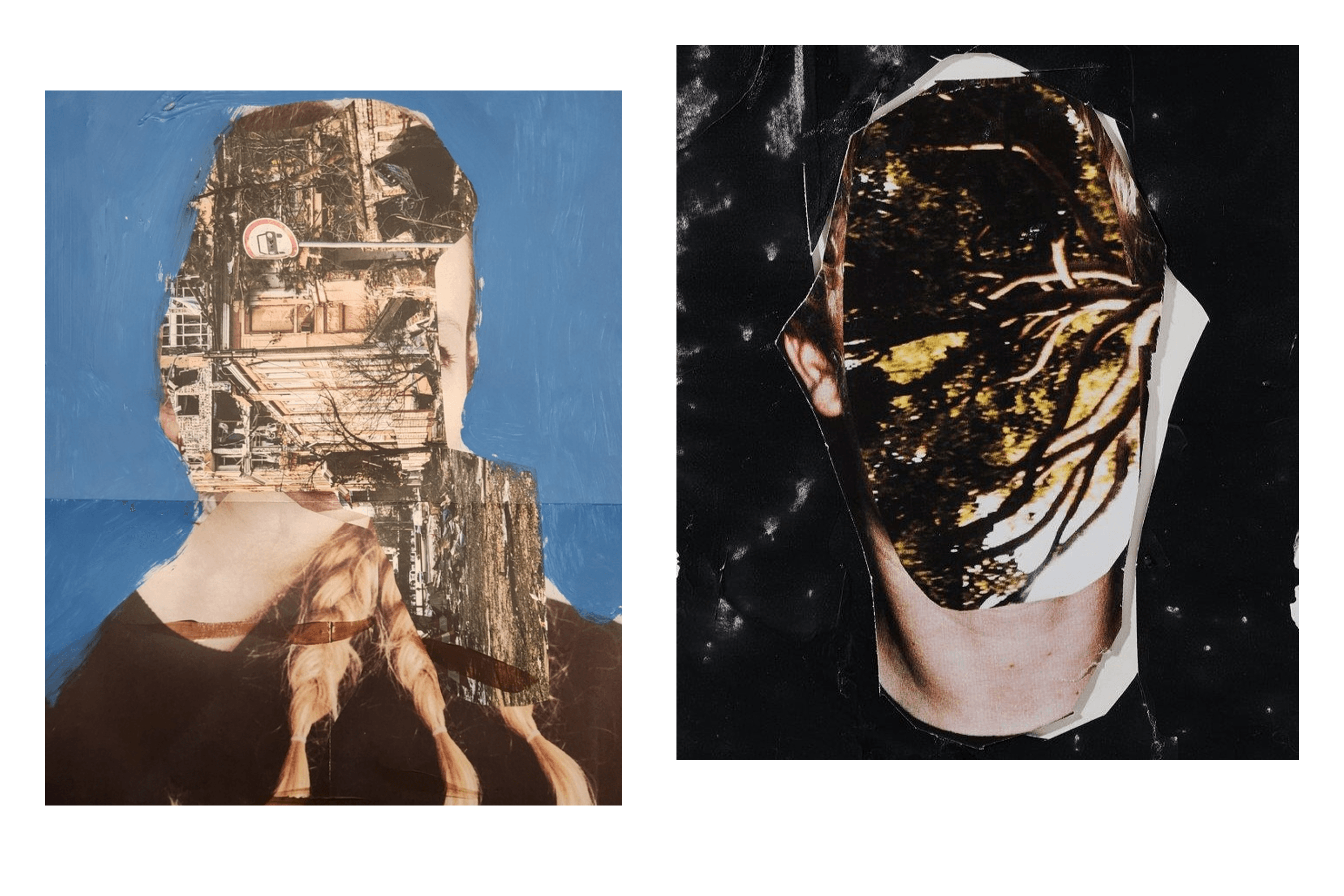

In 2002, Sviatchenko opened his own non-profit gallery in Viborg, Senko Studio, which operated on weekends. For the first few years, he funded the space entirely on his own, and later, the city municipality provided financial support. “It was a purely altruistic project,” he says.“I wanted not only to revive the curatorial ambitions I once had in Kyiv, but also to show that art could be structured in new ways and could influence the life of a city,” Sviatchenko recalls. It was in this setting that he began shaping his signature approach to collage — moving from the typical visual “clutter” of traditional collage to a structured method built around three core elements. This later evolved into his methodological concept Construction — Deconstruction — Reconstruction. These collages are defined by their sharp juxtapositions, created using only two or three carefully chosen components.

Sviatchenko used images familiar to everyone and rooted in collective memory to create what he calls an “aesthetic surprise” for viewers. His works, both abstract paintings and collages, were entirely universal and could speak to any audience, regardless of nationality. And at the same time, he remained distinctly Ukrainian-Danish.

“My identity is Ukrainian,” he says. “The garden, the apple tree, Kholodna Hora — they never disappeared. I still carry them with me.”

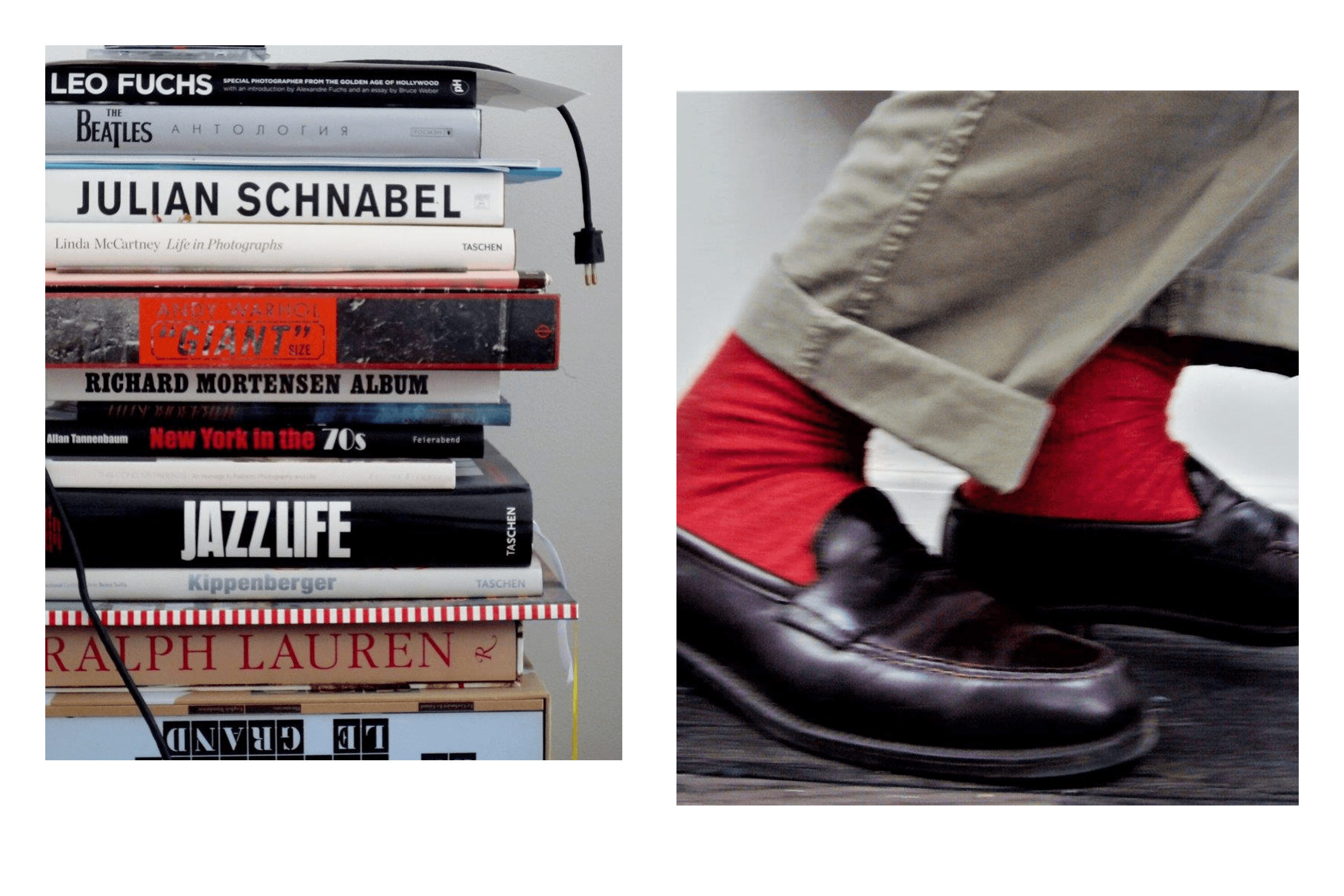

Sergei Sviatchenko grew up in a family where his father and grandfather embraced classic Bauhaus style: polished shoes, carefully selected clothing and attention to details that most people overlook but that shape how a person is perceived. “When I moved to the West, I instinctively began choosing clothing that reflected who I was as an artist and architect,” he recalls. He shopped in second-hand stores, selecting brands that matched his aesthetic principles — the American classic Ralph Lauren and the Japanese Comme des Garçons as a deconstructivist experiment.

In 2009, during Copenhagen’s autumn Fashion Week, Euroman editor Frederik Lentz Andersen approached Sviatchenko, struck by his distinctive personal style, and proposed an interview on the art of style. In 2010, Sviatchenko ranked first in Euroman’s list of Denmark’s 10 most stylish men, a title he held for four consecutive years. Sviatchenko says he has always aimed to transform everything he touches into art. His world is an aesthetic universe shaped by the modernist principles of architecture, visual art, and music by The Beatles and The Doors.

Eventually, recognition also came from private collectors and major international companies. The owners of Grundfos, one of the world’s leading pump manufacturers, created a large private collection of Sviatchenko’s art for their headquarters. In 2009, during Copenhagen’s autumn Fashion Week, Euroman editor Frederik Lentz Andersen approached Sviatchenko, struck by his distinctive personal style, and proposed an interview on the art of style.

And when Denmark was preparing for the wedding of Prince Joachim of Denmark and Princess Alexandra, Grundfos gifted them a work by Sviatchenko, which later became part of the Danish royal art collection.

In 2007, the British studio Non-Format approached Sviatchenko to create the cover for ‘I Dreamt the Constellation Sang,’ an album by Japanese avant-garde musician Motohiro Nakashima. The project required an unconventional approach: the cover included a special pocket that held a poster integrated into the overall album’s concept. Sviatchenko once again turned to collage, and the result earned a Yellow Pencil Award — one of the world’s most respected honours in design and visual innovation. The artist himself did not even know his work had been submitted. “The studio submitted it without telling me. Then out of the blue, a friend from London calls and says, ‘You won a Yellow Pencil! Congratulations! ’” he recalls. This award confirmed for the artist that his work was capable of speaking an international language.

5.

Sergei Sviatchenko first returned to Ukraine in 2017 after being invited to the jury for the Silver Easel competition, where he met his old friend, the artist Oleh Tistol, as well as other artists from the Soviart period. “It felt like an entirely new landscape: new people, new curators, many of whom weren’t even born the last time I worked here,” he says with a smile. He soon became a regular participant in the contemporary art fairs Art Kyiv, where his collages and installations consistently captured the attention of new generations of Ukrainian curators and collectors. While already a well-established name in Denmark, Sviatchenko gradually regained recognition in his homeland.

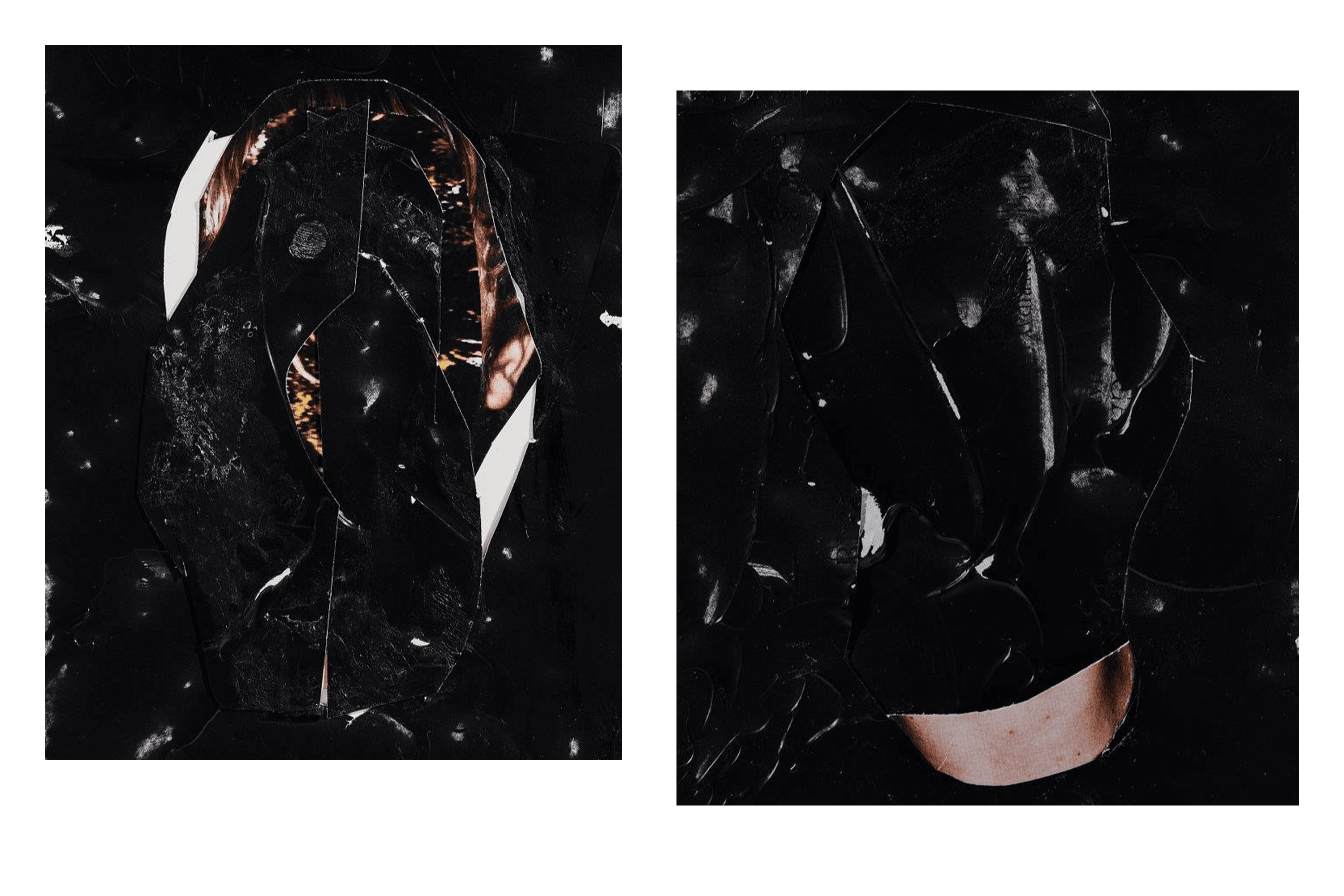

After Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Sviatchenko created a series of works titled ‘Faces of the War. ' It was his attempt to process collective pain through artistic expression. The project was recognized at the International Photography Awards (IPA) in Los Angeles, one of the world’s most prestigious photography competitions.

Sergei Sviatchenko is now 73. And despite an impressive artistic career, he says his greatest achievement is his family. His children — Philip, Erik and Oleksandra — are, as he puts it, “fully Danish,” having grown up with local traditions, values, and everyday habits. “But when they come home,” he adds, “they become a bit more like us again.” Philip works as an Advisor of Strategic Development for LEGO Parks, responsible for global projects across the company. Erik chose sports and today plays in the Dynamo team in Houston in the American Major League, where he is one of the team’s top defenders. “I still wake up at three in the morning to watch his games live,” Sergei says. His daughter, Oleksandra, is a middle school teacher and creates graphic art in her spare time. Sergei’s wife, Olena, an engineer by education, retrained and now works as a nurse at the Viborg hospital.

When asked how he manages to stay relevant decade after decade, Sergei replies: “I’ve never focused on relevance. Everything I create comes through life — through what I see, feel, appreciate, and believe in. That’s what keeps me interested. Life itself makes you relevant, as long as you trust it.”

Today, Sergei Sviatchenko chooses not to work under gallery contracts. Instead, he sells his pieces after exhibitions, at art fairs, and through his own website, which is set to launch an online store in 2026. Sergei now takes on commissions from architectural firms that integrate art into building design, working through the company he founded, JUST A FEW WORKS.

In 2019, Sviatchenko realized a lifelong dream by creating the scenography and costumes for The Nightingale at the Royal Danish Theatre. This project began with a conversation he once had with choreographer Sebastian Kloborg.

A major new project also lies ahead: Sviatchenko has been invited to create the scenography for Boston Dance Theater’s production of Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring. “It’s a dream challenge,” he says. “Music, movement, space — everything merges into a single artistic expression. This is the level of synthesis I’ve been moving toward my entire life.”