Until 2014, Oksana Tverdokhlibova’s life in Donetsk seemed calm and stable. She and her husband ran a shoe business, and their son planned to attend university in Kyiv for directing. However, in March of that year, this stability started to fracture. Russia’s support for pro-Russian forces and covert troop deployment in the Donetsk region ignited the war in eastern Ukraine, leading to the collapse of their business. Oksana and her family moved to Odesa to build a new life, then to Kyiv. In 2022, Russia’s full-scale invasion forced them to flee again.

Now residing in Scotland, Oksana founded Ukrainian Product Design (UPD), a venture that unites Ukrainian product designers and promotes their work globally. Her mission is to elevate Ukrainian design on the international stage. YBBP journalist Roxana Rublevska shares Oksana’s inspiring story.

1.

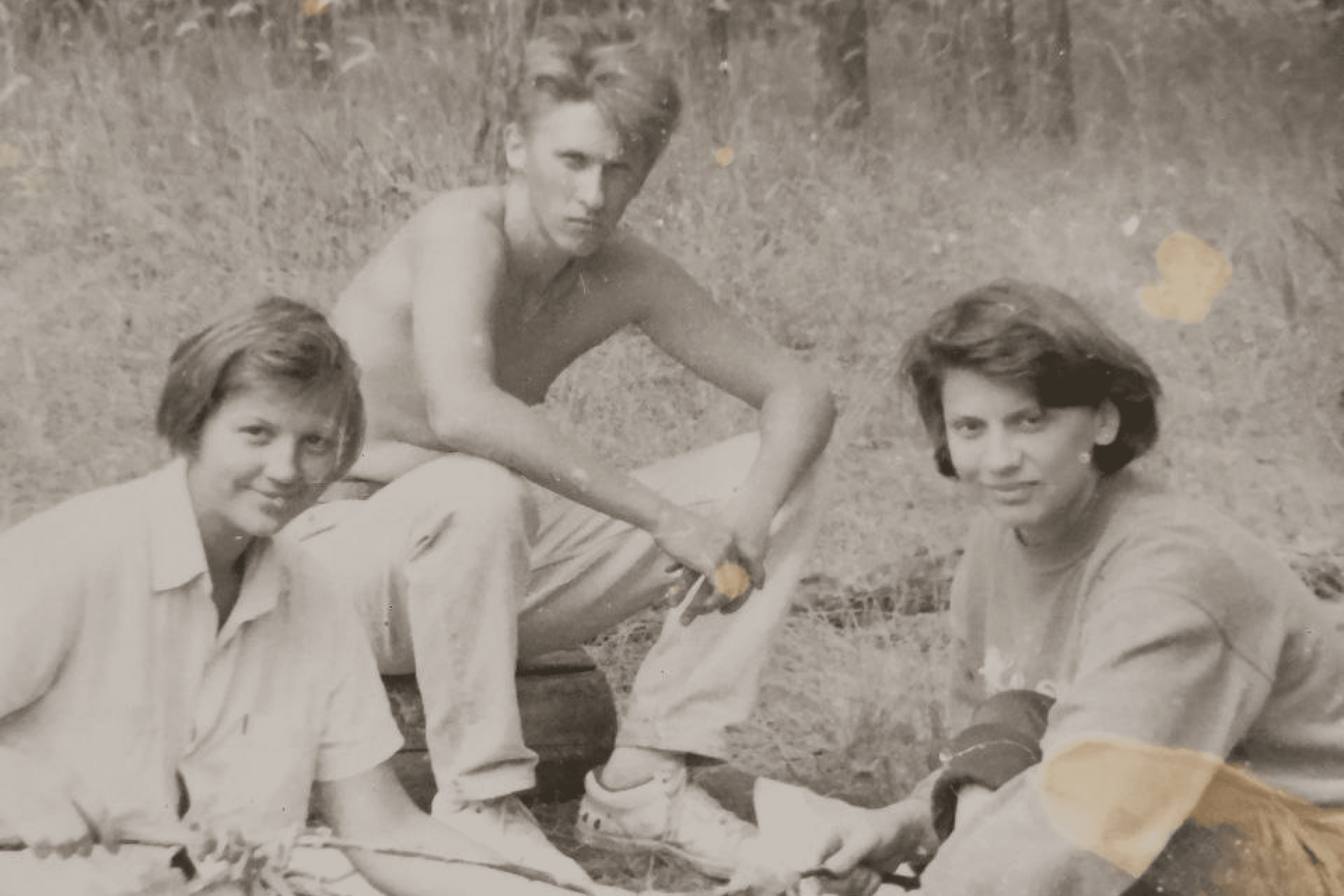

In July 2014, Donetsk entrepreneur Oksana Tverdokhlibova traveled with her son Dmytro to the Odesa International Film Festival, a family tradition for two years. Together with her husband Serhiy, they enjoyed the movies and life in a tent camp. This year, however, Serhiy remained in Donetsk, which was already occupied by local militants and Russian forces covertly involved in pro-Russian rallies. Battles raged as Ukrainian troops attempted to reclaim the territory, though transport connection with the rest of Ukraine persisted.

Oksana and Dmytro felt compelled to attend. Her son aspired to study at the Kyiv University of Theater and Cinema, and Oksana viewed the festival as crucial preparation. The war still seemed unfathomable. They expected to return to Serhiy in Donetsk within a week.

But circumstances shifted. Returning proved too dangerous, and Serhiy urged them to stay longer in Odesa, regularly sending money and belongings by bus. Oksana repeatedly changed her train tickets until one day, at the ticket office, she was informed: "Donetsk railway station no longer exists. It was bombed.”

By then, Oksana and Dmytro had been living in a tent for a month. She and her husband decided it was best for them to remain in Odesa for a year, solely to not let the war steal Dmytro’s dream. In August, Oksana rented a room and enrolled Dmytro in Odesa Gymnasium No. 2 for admission preparation, which accepted him without questions. “We told them we would be there for two months,” Oksana recounts. Serhiy visited Odesa by car every few months, still hoping for stabilization in the East. The inevitability of the unfolding events was hard to believe in.

On September 1, 2014, Dmytro went to his Odesa school. At the assembly, children wore traditional embroidered shirts, and as yellow and blue balloons ascended, the Ukrainian anthem played.

“I remember looking at my child, at the flags and flowers. When the anthem, which had never moved me before, sounded, tears streamed down my face. Then I realized that someone wanted to take away something incredibly important from me. Something I hadn’t even noticed before—being Ukrainian.”

2.

Born in Donetsk in 1976, Oksana spent her childhood in Anadyr, a small town in northern Chukotka, where her mother had moved at the Komsomol’s behest to “develop new territories”, what the Sovied Union promoted young professionals to do. Her mother worked in the seaport’s personnel department and raised Oksana alone. Their small family applied a shift approach: every three years they took an extended vacation to Donetsk, where Oksana’s grandmother lived.

Oksana attended an overcrowded school in Anadyr, which she now credits with fostering her competitiveness. “I studied well, but adventures called, so I had behavioral issues. For New Year’s, I asked Ded Moroz to be a good girl. Now I understand—I shouldn’t have been one then, and even more so, I shouldn’t strive for it now,” she laughs. As a teenager, Oksana convinced her mother to return to Donetsk.

Oksana notes many gaps in her family history. She never knew her father, and her family’s past remained shrouded in secrecy: “Mom told nothing. Neither about her childhood, nor about relatives, nor about her relationship with my father.” Oksana believes this lack of roots became an internal driver; years later, she dedicated herself to Ukrainian product design, seeking to find and connect scattered fragments of identity.

The collapse of the Soviet Union plunged Ukraine, like other former republics, into chaos and economic crisis. Hyperinflation soared to thousands percents year-on-year, and the national currency, coupon-karbovanets, depreciated daily. People received salaries in bags of nearly worthless paper money. “We came from the north, where mom earned something, but when we went to the market to buy a fashionable tracksuit, we could only afford a scarf,” Oksana recalls.

After the 11th grade, her mother insisted she attend a technical school, deeming university too expensive. But Oksana disagreed, viewing higher education as a marker of a decent life. In 1993, Tverdokhlibova enrolled in the Donetsk Polytechnic Institute, specializing in power engineering, gaining admission without connections or money. In her final year, she married Serhiy, her boyfriend of several years. From age 17, he earned money by traveling to Turkey, importing goods, and selling them in Ukraine. It was then that Tverdokhlibova witnessed firsthand how significant money was made at the time. A year later, their son Dmytro was born. But already in 1999, 18 months after giving birth, Oksana returned from maternity leave, driven by a desire for self-fulfillment.

A new building materials store opened near her Donetsk home, where Oksana interviewed and secured a position as sales floor manager.

“It seemed to me that I had found my calling — to change space,” Oksana says.

She aspired to be a designer, independently learning 3ds Max and convincing the store’s management to establish a design studio for her, named “Art of Repair.” “It was my most painful professional fiasco. I achieved everything — space, equipment, support, but I failed. Because Iʼm not a designer. I cannot draw. I saw this and admitted it,” she candidly states.

The store owners didn’t fault her; they themselves lacked deep understanding of the design field, and Donetsk in the early 2000s was far from sophisticated or aesthetically driven. Oksana studied the work of Italian designers through catalogs at the store, learning to distinguish true professionals.

Recognizing Tverdokhlibova’s communication skills, management transferred her to the sales department of a newly opened cottage town branch near Donetsk. Oksana arrived at a desolate field with only one house, which served as the sales department. There, she furnished a client reception room, developed package offers with building plans, sought potential clients online, and crafted personalized offers for influential city residents. “I think I flooded all of Donetsk with those presentations,” she laughs.

Her salary at the time was $500, with an additional $500 for each house sold. In 2002, this was substantial, especially for a 26-year-old woman with no prior sales experience. Within a few years, Oksana achieved consistent sales, earning a salary of $3000. The owners, finding her increasingly costly, fired her in 2006.

3.

Oksana’s husband already owned several shoe retail outlets, and she offered her assistance. The couple decided to expand their family business. Amid the 2008 crisis, as major players like Intertop were closing stores in Donetsk, the Tverdokhlibovys boldly displayed an “Opening soon” poster on four-meter display windows. They opened a shoe store in a former cinema in Makiivka, featuring six-meter ceilings and columns, defying the economic turmoil and currency collapse. “We just looked at each other and asked: are we normal?” Oksana laughs.

Their risky endeavor proved triumphant: as the market reeled, their store attracted customers left without their usual brands. Tverdokhlibova notes they invested approximately $400,000 solely in purchasing the winter collection—a rare volume for local retail at the time.

The couple opened four spacious, prominent stores—two in Makiivka, two in Donetsk—all on central streets, featuring expensive lighting and a steady stream of customers. “We lived so well that there was an illusion, as if it would always be like this,” Oksana recalls.

In November 2013, students protesting the halt of European integration were beaten on Kyiv’s Maidan Nezalezhnosti. Oksana immediately grasped the implications for her son, a future student. This was the initial shock. Yet, Donetsk remained relatively calm, considered an economic capital with a new airport, stadium, and parks built for EURO 2012.

“Donetsk was powerful and self-confident. We simply could not imagine that something would happen to it,” Oksana admits.

In February 2014, after a violent confrontation in central Kyiv, then-President Viktor Yanukovych fled Ukraine. Russian troops invaded and annexed Crimea. Russia then sought to destabilize eastern and southern Ukraine. By early March, mass pro-Russian demonstrations erupted in central Donetsk—particularly on Artem Street, the city’s main thoroughfare, where Oksana’s stores were located.

“I remember that moment well,” she says. “There were rallies, banners, shouts. These were not Donetsk residents. Donetsk residents are different: we work, we look good, we believe in development and stability. And these were completely alien, predatory people—visitors from depressed mining towns or even Russians.”

A new phase began for Donetsk entrepreneurs: survival and business preservation. Oksana and her husband operated on autopilot; the situation’s absurdity made only work feel real. War raged around them, yet inside, inertia prevailed.

Each month, Donetsk transformed further. Retail display windows, once part of a stable urban business landscape, faced threats. The city became dangerous with crowds, armed people, and the first gunshots. Businesses confronted not just a crisis, but a full-scale risk of losing everything—assets, customers.

“We could not imagine that one day there would simply be no city, no home, no former us,” Tverdokhlibova says.

After the film festival, Oksana and her son remained in Odesa, where she found work as an assistant commercial director at a pharmaceutical company. “I brought tea to the director, and he laughed that I was dressed better than him,” she recalls.

4.

In 2015, Oksana’s son secured a state-funded spot at Karpenko-Karyi University, prompting the family’s move to Kyiv. Her husband continued to visit his elderly parents in Donetsk. Their shoe business proved unsalvageable and unsellable, as doing so would have required accepting “Donetsk People’s Republic” citizenship, which the family adamantly refused.

Oksana again sought employment in Kyiv. Despite years of business experience, Tverdokhlibova’s professional skills were ill-suited for the new labor market. Post-2014, Kyiv’s job market intensified due to a large influx of displaced individuals. “It was an incredibly difficult period—I had to start from scratch, and I didn’t feel competitive either psychologically or practically,” she remembers.

Oksana enrolled in an English-language MBA program in project management at the Kyiv National Economic University named after Vadym Hetman. The program spanned 2.5 years and cost approximately $1700. Concurrently, she worked in five different positions, ranging from administrator to senior managerial roles.

In February 2015, Oksana and a friend attended a new collection presentation by Ukrainian designer Victoria Yakusha. She was captivated by what she saw: a table with a clay leg, a liana-shaped floor lamp, a chest of drawers with cookie-like doors—all entirely new and, crucially, crafted by Ukrainian artisans. It was then that Oksana first felt pride in Ukrainian design, recognizing its parity with Italian or French creations. At that moment, she realized: “I want to live this.”

The very next day, Oksana messaged designer Victoria on Facebook: “I want to help you.” Days later, she was completing a test assignment: guiding a potential dealer through an exhibition, persuading him to purchase the exposition, and identifying suitable spaces in his salon for its display. Thus began her career in Ukrainian product design—built on perseverance and passion, without connections or prior experience.

Oksana became the development director of the Faina collection at YAKUSHA Design studio, already internationally recognized for its minimalist style. Several years later, in 2022, Oksana was promoted to CEO. Yakusha playfully nicknamed Oksana “Tank painted in a flower pattern” for her relentless drive and unwavering discipline. However, Oksana acknowledged that while working with Victoria was engaging, it was also challenging due to the manager’s personality.

For a period, she collaborated with renowned Ukrainian designer Serhiy Makhno as sales director. Makhno’s studio was celebrated for its clay products. “He had fantastic people working for him, but there was chaos: no specific price list, no sales system, no collection as such. Each product was unique and not repeated.” Oksana’s mandate at Makhno’s was to systematize processes, establish a functional sales department, and define the product line’s positioning. Oksana boosted Makhno’s product sales by 271% but never received a salary increase, leading her back to Victoria.

Her son Dmytro, a talented and ambitious student-director, worked from his first year, even completing a paid internship with Chad Garcia during the filming of the film “The Russian Woodpecker” about the Chornobyl NPP. However, a conflict with a teacher in his third year led to Dmytro’s expulsion. After overcoming the psychological shock, Dmytro returned to work. Today, he remains in Ukraine, directing for a Ukrainian IT company’s YouTube channel, which targets the US market.

By the end of 2021, Oksana finally felt a sense of relief: she had a fulfilling job in the design sector, financial stability, and she and her husband had invested in a Kyiv apartment, with keys expected in November 2022. Then, the full-scale war began.

5.

In February 2022, YAKUSHA Design studio was rapidly ascending, with international contracts and a backlog of orders solidifying its global presence. On February 24, Tverdokhlibova’s team was scheduled to ship another batch of Yakusha’s products to Belgium.

“We woke up to the news of the war. It was a shock, but significantly less than in 2014. Yes, rockets. But I clung to my usual life: we had a shipment, and I couldn’t sabotage it,” Oksana recalls. Tverdokhlibova, who had just obtained her driver’s license, drove for the first time without an instructor, heading to the office to manually load a massive truck with three colleagues. However, Yakusha canceled the shipment as borders were closed and national processes paralyzed. The next day, Oksana and her family evacuated west to Bukovel, Ukraine, where her son’s IT company had organized employee and family evacuations.

At that time, Yakusha studio received an invitation to Art Basel, a premier global event for galleries and designers, so Oksana continued her work. Upon returning, the family considered their next steps. Her husband, Serhiy, was exempt from military service due to health issues, prompting the couple to consider moving abroad. Oksana, proficient in English, chose Scotland, which was actively assisting Ukrainian refugees. Oksana’s clear intention was to build her own business, not to work for others, though she hadn’t yet decided on its nature.

The couple embarked on forced emigration by car, packed with belongings. Serhiy and Oksana even considered the possibility of living on the streets for a time. However, Scotland’s reception was unexpectedly hospitable.

“We ended up in a hotel where we were provided with food, laundry, cleaning,” Oksana recalls. “And although it was initially for six months, we lived there for two years. This allowed me to recover from the stress and develop my own business project. I worked from morning to evening, not spending time on household chores. That’s how the idea of Ukrainian Product Design emerged. First, I began to establish connections with domestic brands. At the very start, we had eight Ukrainian companies on board.”

Oksana speaks warmly of the locals. “People say Scots are closed, but they are completely different. They are hospitable, sympathetic, always ready to help. I don’t feel any barriers. But the main thing is—I was able to build something of my own here. And, perhaps, that’s what gives me the feeling that I’m home.”

6.

Ukrainian Product Design (UPD) is a platform connecting Ukrainian interior and product design manufacturers with British clients. Oksana registered UPD as an LTD in February 2023, focusing on the B2B segment. She personally developed the website and drafted the business plan.

“We are not just designers—we are coordinators, logisticians, manufacturers, quality controllers. We guide the client through all stages, ensuring transparent communication, including direct contact with production,” Oksana explains.

She joined the Business Gateway program, a Scottish initiative supporting small businesses, and attended master classes in marketing, accounting, and taxation. Individual consultations deepened her understanding of financial and operational processes. Oksana believes doing business in Britain is technically simpler than in Ukraine; it’s nearly impossible to miss a tax payment or report, as reminders from banks, accountants, and government agencies arrive six months in advance.

In April 2023, Tverdokhlibova participated in a trade mission to London with the Ukrainian Association of Furniture Manufacturers. Meetings with local buyers confirmed the necessity of physical product samples for success. This prompted Oksana to set a goal: to exhibit at Decorex London, the premier British product design exhibition, participation in which costs upwards of $67,000. “It became clear: either I find a grant, or there will be nothing,” she states.

Tverdokhlibova secured initial funding for Ukrainian Product Design from USAID. This grant enabled the company to showcase Ukrainian brands in the British market, covering exhibition costs, product certification, a Google and social media advertising campaign, and promotional material production. The first commercial order, for wallpaper, arrived a whole year later.

The team operates entirely remotely, composed exclusively of Ukrainian specialists—a principled stance for Oksana. While there is no physical office, she envisions a large showroom in the future. “We participate in exhibitions, provide comprehensive interior design services,” she says. “For example, last May, a family who bought a house contacted us—they needed complete furnishing, except for the kitchen. That was an ideal case: we took measurements, planned everything and selected furniture.” All partners, from production to logistics, were from Ukraine.

Ukrainian Product Design is steadily progressing toward commercial self-sufficiency. As of 2025, Oksana has begun drawing a salary. The primary advertising strategy targets Great Britain, but orders also originate from France, Switzerland, Sweden, the USA, and Australia, with British clients generating the most profit. The company gains visibility through social media and Google advertising.

Ukrainian Product Design operates in several areas: online sales, collaborations with architects, and B2B complete sets. However, the most significant returns, both creatively and financially, stem from comprehensive project management, where the company selects materials, manufactures furniture, and coordinates all stages. A key current project involves an 850 m² private residence near London. “The client is a sophisticated design connoisseur, who collaborates with Italian and French brands,” Oksana notes. “But individual items, custom-made, we produce in Ukraine. This is a victory: now our furniture is integrated into the space on a par with the works of iconic designers.”

Beyond business objectives, Ukrainian Product Design aims to elevate Ukrainian product design globally. “In Ukraine, a community of product design is actively forming. Someone creates an ideological base, someone promotes brands. And I—sell. My task is to provide manufacturers with a volume of orders.”

One of Oksana’s favorite projects is a three-story private house near Manchester, fully furnished with Ukrainian pieces. She proudly recounts that the entire process—from initial contact to final photoshoot—took only 100 days, a feat that could take a year in Britain: “We launched the process with a budget of €15,000, and finished at €45,000. The client asked: 'Will the furniture definitely be only Ukrainian? ' I replied: 'Only Ukrainian. This is our contribution to victory.' And the client supported us. People here trust us.”

Many European companies, Oksana observes, exhibit corporate inertia—they are slow, limited, and rigid. Ukrainians, conversely, are flexible, fast, and dynamic. They embrace challenges, are unafraid of last-minute changes, and maintain constant communication.

“Recently, the architect of a recreation park wanted to change the design of the railings after manufacturing,” Oksana says. “A shadow seam of 2×3 mm was needed—it seemed like a trifle, but technically it was difficult. We redid it. We won in color, in details—and left behind not just a product, but a wow effect. We win not only in price, but in complexity: design, production, logistics, assembly. And all—with one contact, one voice.”

Oksana visits Kyiv several times a year, each time touring local manufacturers. She describes these visits as a true source of inspiration, consistently discovering new equipment, technologies, and materials. Manufacturers have adapted to new realities to ensure process continuity, installing solar panels for stable electricity, optimizing employee logistics, and organizing multi-shift operations.

Despite successful private residential projects, Oksana sees significant potential in large commercial spaces. “Now a window of opportunity has opened. Due to trade tensions between the US and China, attention is shifting to new markets. And Ukrainian furniture can be the answer. We plan to grow precisely in HoReCa—hotels, restaurants, commercial spaces. This provides scale, systematicity, and constant production load in Ukraine. We want to cover everything from reception to hospitality areas. Turnkey. Just give us space.”