Paul Tkachenko finished school in Ukraine, borrowed money from his uncle to buy a video camera, and started working in video production. After gaining experience in reality and entertainment TV shows, Paul moved on to motion design — “drawn” videos rather than filmed ones: ads, opening credits for series, moving show titles. That is how he became a freelancer, collaborating from Ukraine with clients in the UAE and the US. 12 years ago, Tkachenko came to New York with just a backpack to see the city — and ended up staying, and founded his own motion design company, Crisp Motion.

YBBP journalist Mila Shevchuk sat down with Paul on the podcast I’m Just Asking to discuss how he promoted his business in New York, scored his first client, and the key things to know for working in the US creative scene. The full conversation is here in Ukrainian, and these are the key points we pulled from the podcast.

I was always into the video industry. In high school, I loved telling stories through video. After finishing school, I didn’t study anywhere else: I borrowed money from my uncle to buy my first video camera. I started filming everything I could: weddings, various events. But I found it boring. So I went to work in a production company: I lied on my resume that I had experience with professional cameras and in the industry — that’s how I landed my first job. It was a production company making content for TV. I worked at production companies and TV channels for a few years, then became a freelancer: first doing video content, and later, motion design.

The first clients checked my work to see if I had a feel for video: dynamics, framing a shot. If you had that, you could learn the rest. On my very first day at that first job, I was asking a colleague how to turn the camera on and set white balance. But technical skills weren’t as important as creative vision.

Motion design hooked me because it was the first time I wasn’t working from an office. I could say, “I’m going home, I’ll do this animation in three days and bring it back.” I realized that I wanted to do this so I wouldn’t depend on location or clients in Ukraine, because I really wanted to travel and work while traveling. That was the biggest dream of my life.

You have to learn really fast. This industry never stops evolving, and it’s all about adapting — something Ukrainians are good at. I was learning editing and filming at the same time. I worked with production companies that needed professional content. We produced shows that we sold to TV channels — reality formats and shows about skateboarding or parenting. When I moved into freelancing, production companies would hire me for specialized work: show openers and motion design elements they could reuse constantly, like lower thirds and bumpers.

For a long time, I was a senior motion designer, teaching how to do motion design. Over a decade ago, motion design was still this vague, undefined field. People didn’t know the ‘proper’ way to create it, so most projects looked alike. YouTube wasn’t overflowing with tutorials yet, and inspiration was something you hunted for in the same corners everyone else did. My job was to come up with something new — and know how to pull it off. We used then new software, doing animation in Apple Motion, Adobe Premiere, or After Effects.

I wanted to work with foreign clients because it meant bigger budgets and more challenges. Once, I was invited to work on a production for a client from England. I delivered the project, everyone was very happy — and that’s when it felt like an unlock in my mind. I had always thought that our level was average: you didn’t need to be a genius to succeed in Ukrainian production, because at that time the standards weren’t very high. But when my work impressed the Brits, I thought: if it’s no different from what I was doing in Ukraine, I can do the same for the UK and for other countries. From then on, I started focusing on foreign clients.

At first, I didn’t know how to find clients abroad or how to enter that market at all. In Ukraine, word of mouth worked, but abroad there were just too many people doing the same thing. So I decided to try a method popular among IT freelancers but not yet used in motion design — freelance marketplaces. These are the platforms where people post projects from all over the world, and freelancers compete by pitching prices and portfolios.

Back then, it was called oDesk, later it became Upwork. The timing worked in my favor: Upwork was in the middle of a rebrand and was actively marketing its services. Since there were fewer than a hundred motion designers there, and I already had experience with small clients from the US and Dubai, they reached out and offered to use my profile in their marketing. Upwork was sending emails like: “Check out these motion designers. Maybe you need design, video production, or a website — here are the platform’s top freelancers.”

They gave me a badge for being in the top 1% of freelancers selected by the Upwork team. Thanks to that, when someone searched for a motion designer, my profile was among the first results, and I got a steady stream of projects through the site.

The flow of US clients was one reason I decided to move here. On Upwork, they were hiring people for technical tasks they had already conceptualized. You needed English and the ability to ask the right questions to understand and deliver. But I realized eventually that you had to be an expert in multiple areas, not just motion design, to charge more and stand out.

My international experience started in the Netherlands. I went to Rotterdam because I really wanted to try myself on another stage. I’m flexible, I like risk. Even the flight to the Netherlands was too expensive for me then, so I hitchhiked from Ukraine to Amsterdam, then took a train to Rotterdam. I worked night shifts as a bartender in a hotel, freelanced during the day. I tried to understand how the creative industry worked there. And I felt Europe was too complicated.

I went back home but felt restless. So I bought a round-trip ticket to the States — just a scouting trip. I planned to visit New York, Minnesota, Seattle to see what the US was like, and meet some clients face-to-face in New York and Seattle. Maybe they could recommend me to others. I had no real plan — just this itch in my gut that wouldn’t let me sit still.

I flew to the US with one backpack and told my parents I’d be back in a month and a half. But the next time I was home was six years later. First, I landed in New York, stayed four days, and loved it. Then I went to Minnesota to see a client — didn’t like it. Same with Seattle, even though I had friends there and a place to stay. So I decided to rent a room and live in New York for a month before flying home. And in that one month, very interesting things happened.

At that time, there wasn’t a clear path to legal work documents in the US. I had no money, and nobody could explain how to legalize. I couldn’t head back home because I was tied up with paperwork and couldn’t officially work for some time, so I operated through a registered sole proprietorship in Ukraine. Eventually, I got an O-1 talent visa. It’s valid for three years with extensions if you prove you still have talent, benefit the country, win awards, and stay in your field.

In the United States, you can open a company in 35 minutes, even without residency papers — you can do it from another country. Opening a bank account is harder but still fast. The US is very business-friendly because the government wants your tax money. Lots of websites will do it for a small fee, or you can hire a private accountant to set it up for you.

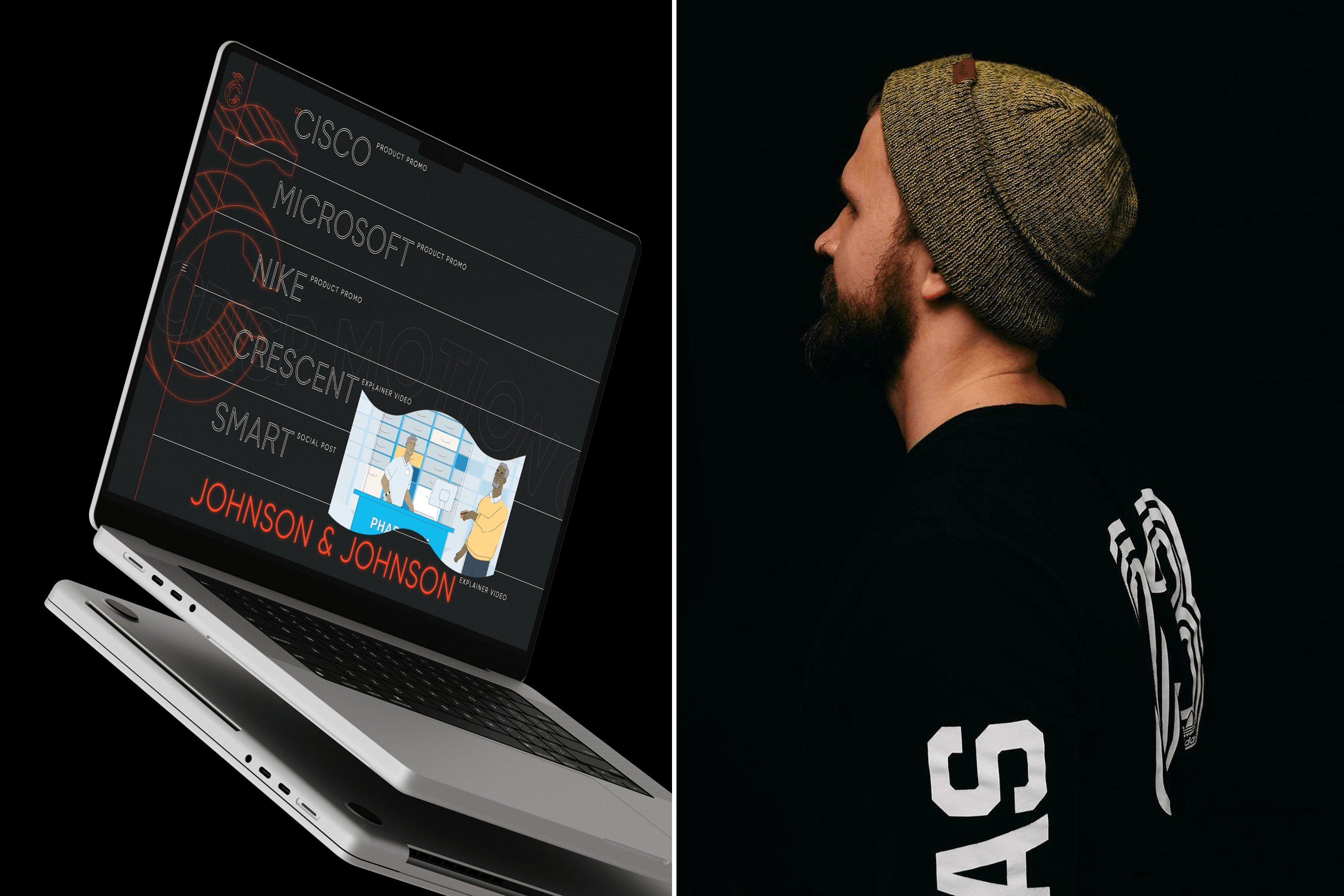

My first step was registering a company in the US. I wanted to position myself as a business, not a freelancer, because that opened doors to bigger clients. Agencies usually work with freelancers and take a cut, but I wanted to deal directly with brands and cut out the middlemen. So I built my own website and business cards.

New York is famous for high prices. When I first came and was starting out, I thought $2,000 a month was enough: I rented a room with a friend, we ate whatever, I barely slept, and didn’t care about conditions. Now my lifestyle costs way more. I’d say around $15,000 a month is comfortable in New York. But honestly, there’s no limit. I know folks who find $50,000 not nearly enough.

I found my first New York client in a coffee shop. A guy sitting next to me, I asked him for the Wi-Fi password, we started chatting. He asked what I do, and said his startup needed exactly that. I’d seen in movies how Americans always say “Oh, you’re awesome, let’s do something together” and then nothing happens — so I didn’t take it seriously. But the next day he called, wired money, and said he needed the work in a week. I did it.

After that, I didn’t fly home. I thought, if I found one client, I could find more. So I decided to stay six months — as long as my tourist visa allowed. In that time, I built a large client base and did lots of work, so I stayed and tried my luck here.

It helps to have competitive companies in your portfolio. If you worked with Volkswagen, you can work with Mercedes. I shifted my focus from street fashion and tech to finance. It’s not enough to just wear a shirt to meetings — you need to know how they talk, what they joke about, and where they live. And the key thing is: corporations aren’t after the flashiest stuff. Everything needs to look pretty simple, and you have to be able to deliver it just like that.

I landed a job at J.P. Morgan and worked there for almost two years as a motion designer. My business had to be put on hold, I only ran it at night. But I really wanted to see the financial industry from the inside. And once J.P. Morgan was on my resume, all their competitors wanted to work with me. That’s how I later got hired by Fidelity Investments as a motion designer — they wanted someone who already knew the field.

There’s a trick to listing big brands: even if the company wasn’t your direct client, but you worked with them through an agency — let’s say you made a three-second text animation at the start of their video. You still participated in the project and have the right to put their logo on your site. Also, nothing stops you from making a project for a big brand on your own: even if they don’t use it, you can say you designed something for them.

My approach to sales is unusual: I go to startup meetups. There are always people who need my services. My first success came in the IT industry, during the startup boom, when everyone needed videos explaining what their company does. That became my niche: I started going to startup conferences for techies. I don’t go to events in my own industry, only where potential clients are. It works: at my first conference I got three clients, and I go to such meetups several times a week.

I pretty much don’t promote my company online. No cold emails, no pitching, and I only update my site and portfolio once in a blue moon. I just meet people and ask if they need my services, or know someone who does. That’s how I built the business, and still 90% of my clients are from New York. I stay here because I know how to do business in this city, and people know me. It doesn’t work the same in other cities — that’s why I love New York.

Expanding the business is exhausting for me — I’m an introvert, I recharge alone, and socializing drains me. At first, I wore a mask, the American smile, and went out to sell. It took effort, but it worked, so I shifted from doing everything myself in motion design to hiring people to handle the work while I focused on communication, finding clients, and growing the business. The last two years, I lived in London and Portugal, and for a while in Los Angeles too.

LA is closed off: to meet people, you need someone to “introduce” you. In New York, you step outside and see people right away — cafés full of folks open to chat. LA is car culture: people either sit at home far from neighbors or drive everywhere. Random encounters are rare — you need to know someone to get into a private party.

California also has its own mentality: people don’t want to offend you, they always smile, “We love your work, awesome, we’ll definitely do something.” And then they can drag it out for months. In New York, they’ll tell you straight up: ‘Hey, what you’re doing doesn’t interest us.’ It’s honest at least, and you save time. Some people can’t handle that bluntness, but I’m fine with it.

What I like about New York is that the competition here is pretty friendly. Feels like there’s enough money for everyone, and if you’re doing the same work as me, it doesn’t mean you’re taking my bread. In general, people support each other: we often meet with competitors and talk business. Of course, competition exists; everyone tries to stand out.

In New York, nobody cares where you’re from. There’s no “Oh, Ukrainians are good programmers, let’s hire them.” You have to become one of them — understand the culture, speak the same language. Many Ukrainians make the mistake of staying in their bubble, only knowing Ukrainian brands, businesses, and communities, closed off from the new and from the culture local businesses operate in. New Yorkers sense that instantly — sometimes even in the first Zoom call.

I decided to integrate right away and never spoke my own language. Usually, people seek out the Ukrainian community because it’s easier and safer. But all my friends were from the creative scene: Americans or other immigrants. That helped me learn the language to the level needed for creative business and to understand the culture — jokes, references, pop culture. That’s crucial. Even someone with perfect English, who has just arrived from Ukraine, might not understand what’s going on at a creative event and may not be able to follow the conversation.

My advice is to add big names to your portfolio as soon as possible. Location doesn’t matter — the client does. If it’s Volkswagen, it doesn’t matter if you did the job in Germany or Ukraine. If you delivered for a brand everyone knows, they’ll assume you can deliver for them too. But if it’s local brands nobody has heard of, then it doesn’t matter if they’re from Ukraine or the US — it’s irrelevant.

A common mistake is offering cheap service. I did that too, hiring people in Ukraine to do it cheaper. I thought this could help me stand out among competitors. But clients are wary: if it’s cheap, they assume it’s low quality. Plus, when you tell them the team is based in another country, it raises fear and distrust.

Second mistake — lack of expertise. If I do everything for little money, it’s unattractive. Saying “I’ll do everything, and it’s cheap too” might sound cool, but it really means the person isn’t deeply skilled in any field and just using cheap labor. This is why now I position myself as an expert in a specific field — finance.

I stopped charging by the hour a long time ago — the client pays for the project. I like this model, because there’s no limit or standard. The realistic price is $10,000-20,000 per minute video. But it all depends on your relationship with the client and how you present and sell yourself. One client might think my knowledge is worth little, another — that it’s extremely valuable. For example, a two-minute animation for a bank averages $18,000-20,000. However, hypothetically, someone could charge $30,000-100,000, while someone else does the same for only $800. It all depends on you.

On payments — everyone signs a contract. If you just agree verbally, as they say here, it’s on you. And what do Americans do when they lose money? They love to sue. And the courts work: any contract is valid, so we sign one with every client. I haven’t had to go to court yet.

In the US, everyone talks about money. It’s the main measure: how you’re doing in life, if you’re okay, your lifestyle. It feels like there’s endless money here and everyone’s chasing it. Nobody comes to New York to lie in a hammock with a cocktail — they come to earn, build careers, and businesses. Over time, it gets exhausting. That’s why I went to Europe — to see how people live without being obsessed with money. Money brings freedom, but when the whole culture is about earning more, it pulls you away from real values. Europe’s big on slow living and slow food.

Now I’m one of the most expensive players in this industry. When people hear my rates, they take it as a sign of quality. Of course, you need to explain why it’s expensive, but high price builds more trust than low price.

Finance is a very sensitive sector: in design, there are many nuances that can cost dearly. For example, in visualizing investments, just showing an arrow going up can be taken as a guarantee of profit. If profit doesn’t come, clients can sue the bank. That is why finance companies don’t want to explain this all to a designer and are ready to pay $15,000–30,000 for a video — it’s an investment in safety. Losing billions in lawsuits is a worse outcome. So they choose expertise and pay more.

Creating one motion design video takes from three weeks to half a year. In finance, it takes that long because of legal checks: making sure there’s no banned or misleading language, diversity is represented correctly, and sensitive aspects are shown properly. Lots of approvals. And the longer the video — maybe 3 minutes, maybe 20 — the more checks.

It really feels like AI is right on our heels. People see tons of AI-generated content and start asking: “Does this really need to cost so much? Can’t we do it in five minutes? Perhaps we should hire an intern to quickly whip up what we’re paying big money for?” It clearly undercuts the market; prices are dropping. Obviously, AI doesn’t give the quality we do, but it does “good enough” and not in a month, but in half a day. That is scary, though I hope we will use it as a tool to shorten work time.

It’s worth developing skills in presenting, giving and receiving feedback, negotiating. And of course, networking. Back in Ukraine, small talk felt unnatural: nobody understood how it worked. It seemed weird to approach a stranger and say, “Nice sneakers! Where did you get them?” — and start a conversation like that

Don’t be afraid — everything is possible. Develop your skills, surround yourself with people you want to be like, who’ve already succeeded in this industry. Don’t stay in a comfy environment where everyone’s just starting: that way, you’ll be “starting a business” forever without actually running one. My rule is simple: choose an environment where you are the least experienced one, because that’s how you learn from those around you.

I want to get back to what I started with — video content. With all the AI-generated stuff around, videos are losing that organic touch. I want my business to run on its own, and I’ll be making stories about real people, filmed by real people, which I think is super valuable and will soon be rare.