Larysa Didkovska is the rector of the Ukrainian Free University (UFU) in Munich and a psychotherapist who studies what Ukrainians are experiencing during the war and how to cope with it. She holds a PhD in Psychology, is an associate professor at Ivan Franko National University of Lviv, studied at the Paris School of Gestalt, and completed a five-year program of the European Association for Psychotherapy. In addition, Didkovska writes books on the psychology of emigrants and their socio-cultural adaptation.

Journalist Mila Shevchuk from YBBP met Larysa Didkovska at the UFU in Munich to ask her how to build a personal sense of “okay” in a new country, which adaptation strategy is the most constructive, and why returning home can also be a form of loss one has to pay for. Below are the key points of the first part of their conversation; the full podcast with Larysa Didkovska is available here.

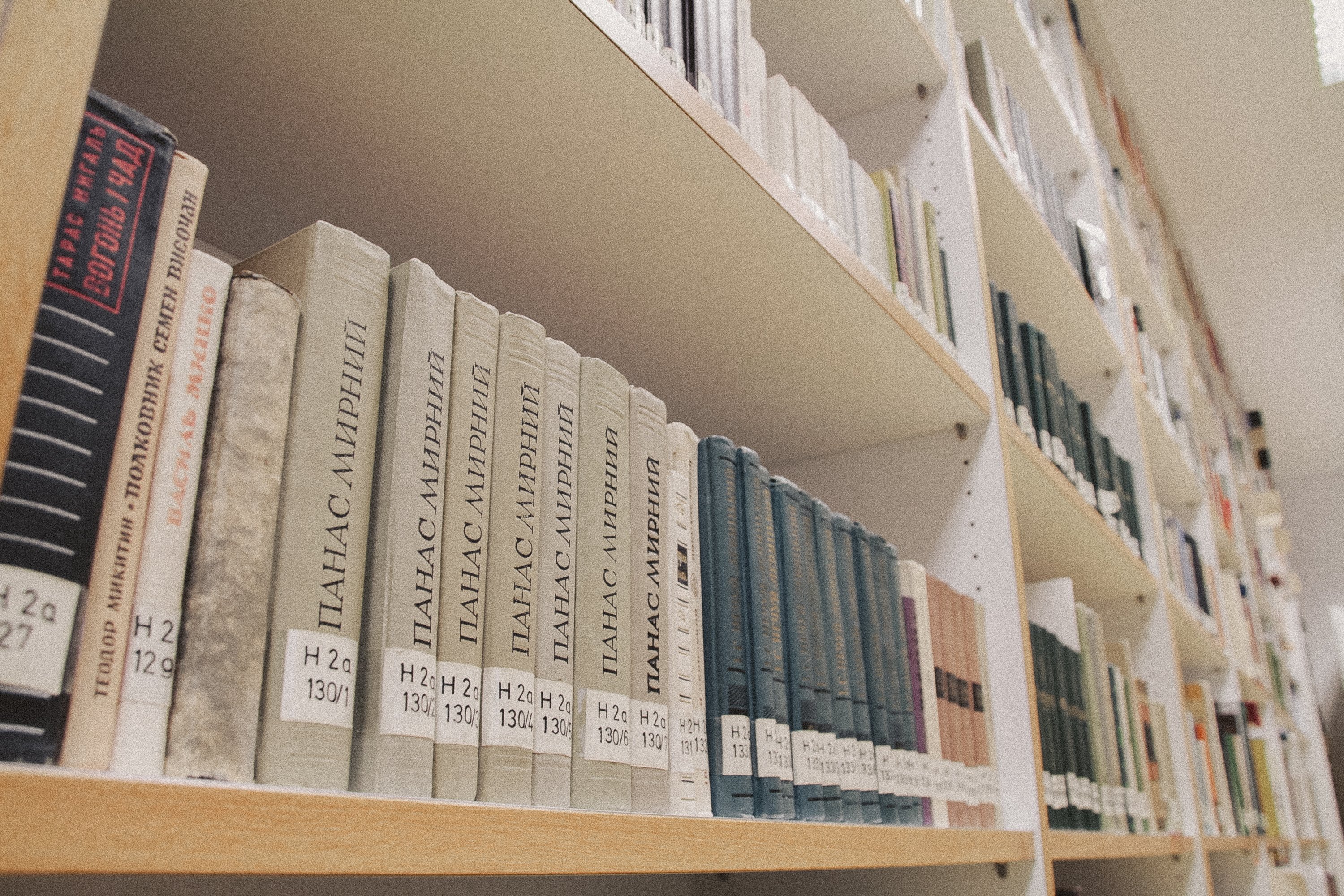

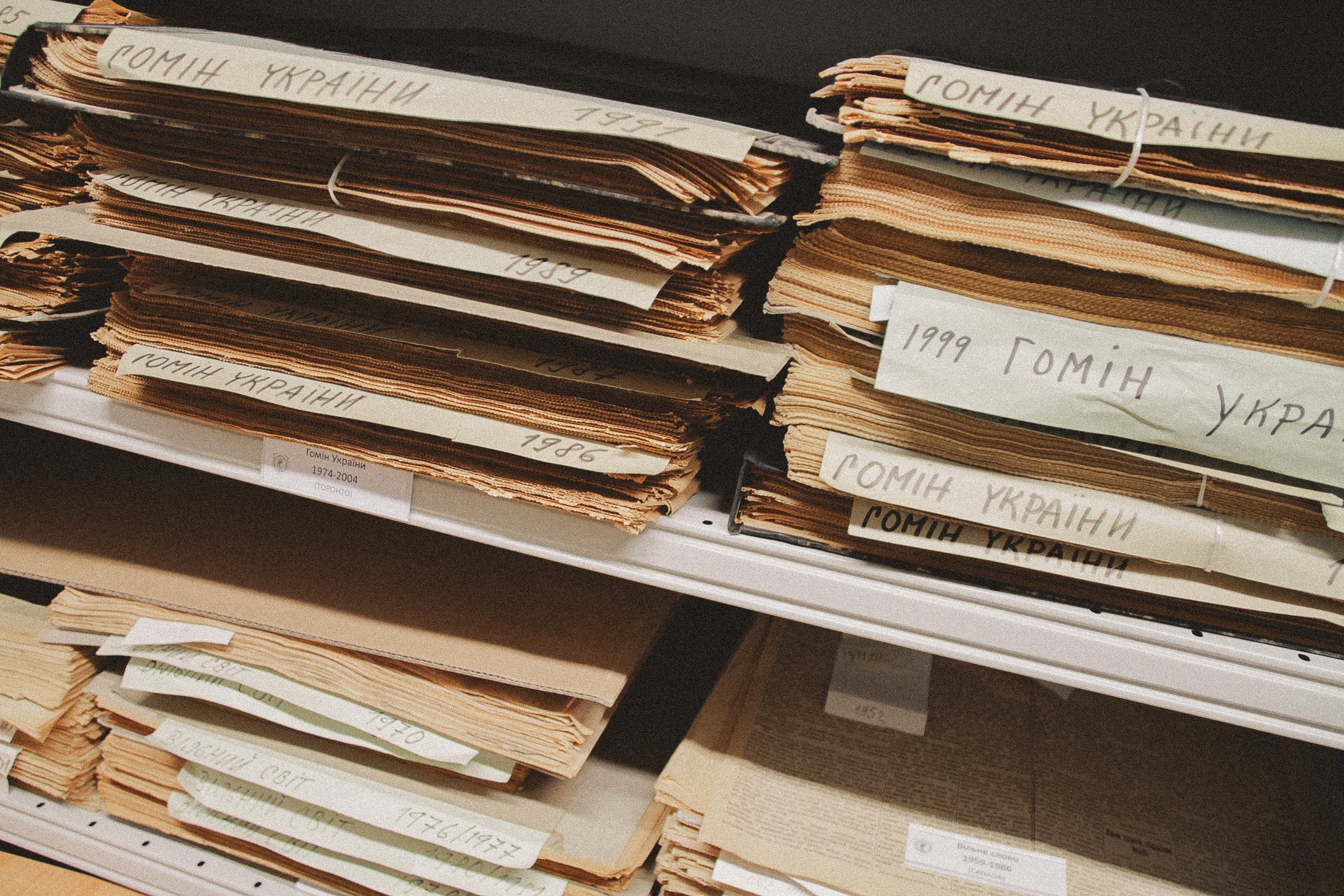

Ukrainian emigration began at the end of the 19th century. This wave of migration was described by Ivan Franko, Olha Kobylianska, Pavlo Hrabovskyi, and Arkhip Teslenko. It was triggered by pre-war poverty, especially in Western Ukraine, where, due to high population density, there was not enough land; it simply could not be divided among all the children. That was the time when the idea of the “Wild West” appeared. The late 19th and early 20th centuries were not only an era of revolutions and social upheavals but also of new possibilities for movement: ships and railways were already operating, not just carts and horses. This was a labor migration, an attempt to find land to cultivate. Literature of that period depicts these stories, as in “The Stone Cross,” where despair was felt as the whole village gathered to read the first letters from those who had left, or to learn from newspapers about the opportunities of an unknown American world.

There are several approaches to interpreting the waves of Ukrainian emigration. Some historians count fewer wartime migrations and more postwar ones, speaking of four, five, or even seven waves. The main marker is the cause. There is temporary economic emigration. There are people who try living in different countries, calling themselves “citizens of the world.” There is student and labor migration, as well as protest migration – when someone has wronged you and you leave your homeland because it feels hostile. Dissidents emigrated because they were escaping prisons or forced psychiatric treatment.

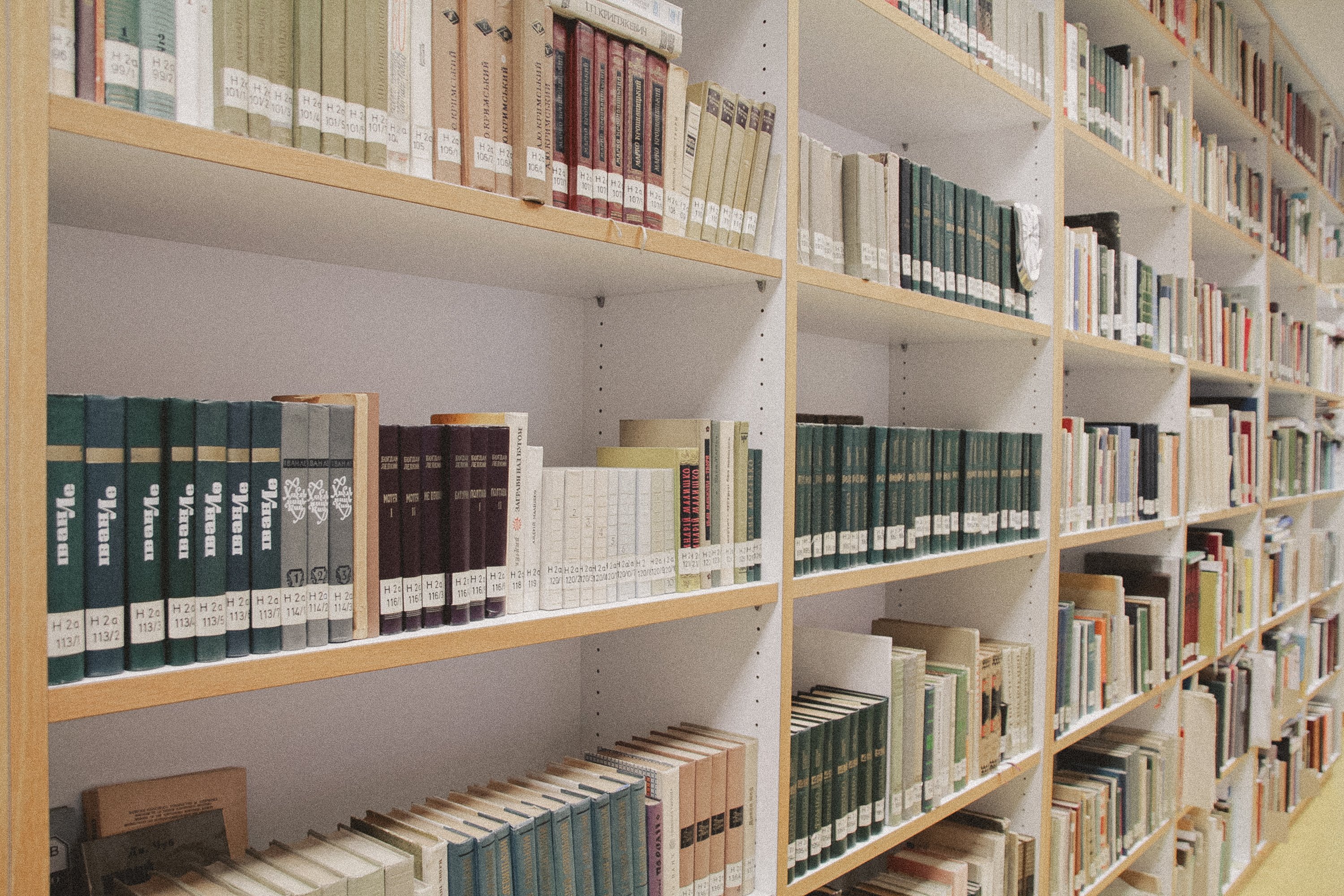

The history of UFU is also the history of Ukrainian emigration waves, particularly those connected to World War II and the DP camps. The Ukrainian Free University is now in Munich, but it was created in 1921 to save the lives and work of Ukrainian teachers and scholars. At first, the university was located in Vienna, but that proved financially unsustainable. Thanks to the policy of Czech Prime Minister Tomáš Masaryk, who was very sympathetic toward Ukraine and its people and offered financial support, the university moved to Prague in the autumn of 1921. It remained there until 1945.

At the end of World War II, the university had to flee again, this time to Munich, because it was part of the American zone. There is a portrait of the Ukrainian scholar and political figure Augustyn Voloshyn, who was a professor of pedagogy, dean, and rector of UFU. He was first arrested by the NKVD and then executed, despite his international reputation. Europe at that time was being divided among the Soviet Union, the United States, and the native European states. Many people moved to where the U.S. protectorate extended – including our university. That was the origin of the famous DP camps, which also existed in Munich, for displaced persons. The war ended, and people faced a choice: be condemned by the Soviet Union and end up in Siberia, or save their lives in Europe.

I began researching the topic of emigration because for some time I lived between two countries: my family and I lived in Toronto, Canada. My son was studying at the university there, and I was working as a psychotherapist. I still work with emigrants today: some of my American clients remain in online therapy. The stories I heard from emigrants were often more dramatic, sadder, and quite different from my experience of psychotherapy in Ukraine. I became curious: why do people face one set of problems at home, but when abroad, new ones appear while the old ones vanish? It was also a professional interest of my husband: in Canada, access to libraries is excellent, and there he studied emigration topics using English-language primary sources.

Most waves of Ukrainian emigration were wartime. There is planned emigration, when people consciously make the decision, and then there is emigration when people are simply forced to save their lives and end up in a foreign world where safety is greater.

In a foreign world, people try to preserve familiar things. That is impossible. When they fail, it leads to frustration and dissatisfaction. At these stages of processing loss, the most common issues arise: “ I lose my sense of purpose in life, and I’m going through depressive feelings,” or “we have family conflicts.” People do not immediately connect this to the emigration process and the transformations triggered by relocation, so they complain about others: the children are less obedient, the husband doesn’t understand. In reality, it’s not that these people have become worse – it’s that the old world was the environment that shaped your life and identity. Adapting to a new world is a process full of challenges.

My husband and I spent 15 years co-writing a book on the psychology of emigrants. It is meant to be a scientific trilogy. With the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the subject has become even more relevant. We self-published the first book, and 1,000 copies sold out within six months. The following two books, already published, deal with socio-cultural adaptation in emigration, and the planned final part will focus on psychological adaptation. There is interest in translating these books into German, English, and Polish. But my biggest dream is to publish not an academic book, but a popular guide on how to navigate the transformations of emigration more smoothly. Because the main purpose of my profession is to help people manage their lives more effectively and healthily. Not necessarily more easily, but certainly with greater awareness.

Since 2022, the portrait of the Ukrainian emigrant has changed dramatically. Today, we are witnessing a quantum leap for our nation. We are showing the world that we are a nation of dignity and courage – not only a nation of migrant laborers, but of educated people, not second-class citizens as portrayed in the old myths of our imperial neighbor to the east.

Emigration means living through stages of loss: shock, denial, anger or aggression, devaluation of everything around you, and idealization of what has been lost – these are the phases described in emigrant experiences. Then comes the bargaining stage, as Elisabeth Kübler-Ross wrote, although other classifications exist. But re-emigration – returning to one’s homeland — is also a stress and a crisis. By then, a person has grown used to the comforts of a new world, and their absence at home is perceived as a loss. What once frustrated us in a foreign environment as unfamiliar and uncomfortable, now starts to frustrate us back home, because we have become accustomed to no longer facing certain everyday or social problems in our lives.

Adaptation mechanisms are activated once the affect has passed. We stop thinking with the “reptilian brain,” which reacts only to safety or danger, and begin to analyze consequences and make predictions. At this point, IQ recovers – which during affect drops by about a third. For example, two weeks after February 24, the mayor of Przemyśl spoke of 14 million Ukrainians passing through the city, but within a few months, 8 million of them had returned home. Why? Because the initial shock, fear, and first phase of stress from danger had passed.

The loss of social status is a form of downshifting, which creates a narcissistic wound. If you are a lawyer, but the legislation of the new country is different. If you are a lawyer, but the legislation in the new country is different. Or if you chaired a department or defended a dissertation, and that is no longer relevant. Some professions, however, are easily transferable: a programmer in Ukraine, Britain, or the Czech Republic performs the same tasks. A truck driver in Ukraine, Germany, or the United States still performs the same function, only the roads change.

Waves of emigration are more likely to return to Ukraine when departure was forced by danger rather than a conscious choice. If a person has other motives and prepares in advance – learns the language, searches for work, studies the legislation of the new country – that type of emigration is more deliberate and usually doesn’t include the idea of going back. In contrast, emigration without preparation, careful decision-making, language study, or financial security – as in wartime emigration – carries a higher likelihood of return, because it was not a conscious intention or desire, and therefore resistance arises.

Time is a crucial factor: after three years, the likelihood of return decreases. When we leave our homeland, the life we had there gradually fades, and the new life abroad becomes our own. Ukrainian socio-economist Ella Libanova conducted a survey in the first year of Russia’s full-scale invasion about intentions to return home: at that time, more than half of Ukrainians planned to do so. By the fourth year of the war, that number had fallen to more than a third, but less than half.

Coping strategies can be constructive or destructive, and abroad there are different paths of adaptation. One is marginalization: when you lose your national identity and professional standing, but also fail to master what surrounds you – this is ineffective. Another is integration into the foreign society, when you become part of it – this is more effective. There is also acculturation: when you stay within your own groups, attend Ukrainian churches, communicate only with the diaspora, and do not learn the local language. This approach is completely maladaptive: you can spend your whole life abroad, like on Brighton Beach in New York, without learning English, and just keep your own customs and place names. Encapsulation allows you to remain yourself but without interacting with the outside world. The best strategy, then, is integration: joining the surrounding world, respecting its laws, while preserving your essence and identity. You simply add new skills to what you already know and can do.

Some people are more adaptive, while others are inert and rigid. Even before our era, Hippocrates made the first typology of such differences. Beyond psychological traits, age also plays an important role. There is a saying: “An old tree cannot be transplanted.” The latent period for the development of speech falls between the ages of two and five. If a child enters a linguistic environment during this time, within a few months, they begin to speak in a way that others can understand. For adults, however, learning a language is much more difficult. At the start of life, we are a tabula rasa, a “blank slate,” but with age, it becomes harder to make space for new experiences. According to Jean Piaget, identity – national, social, cultural – forms by around the age of twelve.

In emigration, we are a foreign body marked by the distinction of “ours” versus “others,” and that brings more danger. If we did not share a common childhood or culture, we would need to learn a lot to understand another culture. Some people are ready for such an encounter, while others may feel afraid, resist, devalue, or judge it. Some proverbs illustrate this: “There’s no place like home,” “East or west, home is best,” “Sticking out invites trouble,” and “When in Rome, do as the Romans do.”

We all inevitably face loss. Sometimes we even lose interaction skills: in Ukraine, you can drop by someone’s house without warning, but this is not acceptable abroad. In Germany, celebrating a birthday at work would be met with surprise. Even offering others all the food you’ve prepared can be awkward – to them, it is unfamiliar and may not be appetizing. People might show reluctance or even disgust. If you take it personally, you will be hurt. It’s better to ask: “Hey, I’ve got this, would you like to try it?” – but you must be ready to accept a “no.”

We come from a collectivist culture. In individualistic societies, personal privacy, independence, and autonomy are considered untouchable. But there are countries where “I am you, you are me.” In many Asian countries, there is no separate character for the pronoun “I”, it is expressed as “I am the son of my parents,” “I am part of my village,” or “I am an employee of the company.” In other words, people immediately see themselves as part of the community.

Multiculturalism often boils down to formal relationships without deep attachments – without grandma’s lullabies or the shared baking of traditional bread. In emigration, children did not see their parents caring for their own parents or visiting old classmates. Instead, they saw their mother and father working a lot. And they learned small talk.

Sometimes, different generations of emigrants hardly interact with each other. I am most familiar with Canada in this regard, as a psychotherapist, having worked with hundreds of clients there. An achievement is that five generations of emigrants – four of them not born in Ukraine – continue to speak Ukrainian, bless Easter baskets, and bake their own paskas. They did not lose touch with their homeland, even when information resources and air travel were unavailable. So they created Ukraine in Canada: they built churches, named villages with Ukrainian names, organized music ensembles, and Ukrainian schools for children who had never seen Ukraine.

The first waves were impoverished – monuments to those settlers in Canada depict a saw, an axe, a measure of grain. Later waves, however, came with different motives: to improve their quality of life. They arrived financially secure, with bank accounts, good knowledge of the language, transferable professions, and sometimes the support of migration agencies. There’s some envy toward the newcomers’ better financial situation. Still, also a sense of hurt, because the first migrants left without abandoning their homeland – they didn’t have an independent Ukraine where they could earn a decent living. That hurt can feel like a kind of betrayal, even though the first migrants weren’t betraying anyone – they were just trying to survive.

The United States united all immigrants around a shared identity rooted in the future. This is called the Great American Dream. Everyone arrived in search of a better tomorrow, and what bound them together was the desire to build prosperity for themselves. A common motivation has always been migration for the sake of the children: I want my kids to have an easier and better life than I had when I was growing up.

Ireland has a successful experience from the 1980s–1990s, when the government encouraged emigrants to return. At the state level, they implemented special reforms, benefits, and free education, making it more advantageous for students to return to their homeland. The same goes for Poland: it experienced large-scale labor migration. However, socialist-era Poland was significantly different from contemporary Poland within the Schengen Zone. When living in Poland became better than working in Britain, Canada, or elsewhere, people returned home, now financially secure. After all, the European Union and the Schengen zone mean safety, democratic laws, and freedom of movement. They mean longer vacations than on the American continent. They mean grandparents who can actually spend time with their grandchildren. They also mean minimal cultural distance – and that is a critical factor for adapting in emigration. When your homeland becomes attractive and safe, not only financially but also socially, it becomes a better place to live.

Statistically, rates of mental disorders, suicides, and divorces are higher among emigrants than among the native population. Emigration is not an easy kind of happiness. There are no cheerful emigrant songs. But this is not a verdict. Every year, up to 200,000 native Britons leave their homeland. And at the same time, millions of emigrants are striving to get into England. It is a dream country, but not for those particular 200,000. Are children sometimes happier at daycare than at home? Yes – if home is worse: no toys, not enough food, or constant mistreatment. In that case, daycare becomes a space of joy. Something similar happens with emigration. Is it really okay if a child feels happier at daycare than at home? No, because home should be a place of safety, love, and acceptance. But homes are different. If people feel uncomfortable at home for economic, social, or psychological reasons, it’s entirely possible for them to find happiness in another country.

Idealization brings with it a storm of emotions and painful feelings. The healthiest attitude belongs to people who neither deny the advantages of their homeland, nor idealize it, nor disparage the foreign land. When we fall into polar extremes – either devaluing our own country or, on the contrary, idealizing it while constantly finding fault with the new one – such judgment destroys our inner balance. The balanced approach is to make a mindful choice and accept its price. No matter the country, you can find what brings you happiness.

War polarizes the world in every way: those who left versus those who stayed, those on the front versus those who avoided it. From our divisions and confrontations, only our enemies benefit. As long as the war continues, our strategy must be the same as the Americans once had: a shared identity rooted in the future. For now, we must be less demanding about our differences and more attentive to what unites us: the victory of our country over the aggressor, the rebuilding of Ukrainian cities, and the preservation of national identity. Psychotherapists who work with concussions and PTSD are not on the front line either, but they are still serving the front — because they help those who lost their mental health there.

There is a saying by a German philosopher: “Language is the homeland that always stays with you.” Wherever you are, by speaking Ukrainian, you remain Ukrainian and show that to the world. Children can be taught Ukrainian, shaping their national identity and continuing the struggle for a sovereign Ukraine. This, too, is a path toward uniting around a shared dream.

Those who have gone abroad often feel guilt. It’s the survivor’s guilt. Soldiers at the front feel the same when someone next to them dies. It is irrational: under the same circumstances you survived, and another did not. There are eight billion people in the world, alike in our emotions yet unique in our fates. For some, emigration becomes a pedestal that brings them a prize; for others, it leads to despair or even suicide. Around two hundred factors shape a personality, which is why people adapt – or fail to adapt – in very different ways. It all depends on the adaptive resources of the body and mind.

Every choice comes at a price. Because choice is, first and foremost, about loss. Do you stay and live under shelling, or do you lose your homeland – everything familiar – and end up in a foreign world? Any of these choices carries a cost. To arrive elsewhere, you must be ready to let go of what must be left behind. There is a parable about Buridan’s donkey, which found itself between two haystacks. It walked toward one, then turned to the other, which seemed tastier. It moved toward the better one, but kept looking back at the previous. What happened in the end? The donkey died right in the middle, because it wasn’t ready to give up either of them. If we believe the illusion that returning to Ukraine will be easy – it will not, because we must give up what was good in emigration. Likewise, some imagine that life abroad will be carefree, with the security they’ve always wished for. But reality isn’t either/or – it’s both/and. If we’re afraid of losing what we had abroad, or keep looking back at home in despair, we risk ending up like that poor donkey.

There are two paths from traumatic experiences. The same survivor’s guilt can lead to self-destructive behavior, like turning to alcohol, or it can become a motivation for personal growth. Post-traumatic growth is described even in folklore: “One down, two to go” and “What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.” And there will be people for whom wartime emigration becomes a source of post-traumatic growth: they will learn a new language, acquire new skills, and find ways to support their homeland, even while not being physically there. This, in turn, becomes a constructive strategy.