Kateryna Kyrychenko has worked on 26 documentary films about Ukraine, yet she doesn’t consider herself a patriot. She was born in Siversk, Donetsk region, into an ordinary family and was a good student. In the late 1990s, she became interested in computer technologies and was admitted to the Luhansk Taras Shevchenko National University without exams. She then took a risk, moved to Kyiv, and enrolled in a state-funded program at Kyiv National Economic University (KNEU) specializing in economic cybernetics. Immediately upon starting her studies, Kyrychenko launched a confectionery business producing tons of cakes daily, owning trucks, and managing logistics across Ukraine. She later authored books on HoReCa business optimization and consulted various hotel and restaurant complexes.

Then came a sharp turn: after seven years of working nonstop, Kateryna and her husband sold the business and decided to pursue their dreams. This led her to acquire a second degree in film directing, work with the renowned Ukrainian director Oleksandr Muratov, and begin creating documentaries about Ukrainian history and talented Ukrainians. It was this activity that led Russia to place Kateryna and her colleagues on a wanted list after the full-scale invasion in 2022. She then moved to Australia, to the city of Sydney, where at the age of 36 started everything anew. Kateryna established her own video production company, naming it after her former business—Luxintegro.

YBBP journalist Mila Shevchuk spoke with Kateryna about the realities of life and business down under, her volunteering for Ukraine with the New South Wales diaspora, her participation in UN events, and the challenges of Ukrainian diplomacy in Australia.

Getting into the confectionery business

You were enthusiastic about mathematics and computer technology and enrolled in economic cybernetics. How did a confectionery business arise from that?

I met my future husband at KNEU. He was an orphan and grew up in a children’s home. Kyiv was an incredibly expensive city for us, so we took up side jobs. In the 2000s, coffee shops were opening, but they lacked desserts. And everyone wants a little something with their coffee. So, in the summer of 2005, I baked small cakes and pastries, and my husband handled the delivery. In the first month, we earned $350, which was a lot of money at the time. By September, we had rented a small bakery, and a year later, we built our first dedicated workshop near Kyiv. Simultaneously, I worked at the Cybernetics Department of the Kyiv National Agricultural University, earning a $150 monthly salary.

That was a fortunate time for starting a business. Within a year, we were baking up to a ton of desserts daily, and within three years, that volume grew to 3–4 tons, and we owned three lorries. Our yellow cake packaging, featuring Ukrainian embroidery, became a staple in all wholesale databases. In 2008, we had three workshops: two we built ourselves, and the one we rented and then bought out. We had 50 people on the payroll working in two shifts. However, we weren’t taking home significant profits; we were constantly reinvesting everything back into the business, rarely taking a rest or traveling.

Did your education help you in the business?

It taught me the core principles of process optimization. My husband handled the logistics. He’s a very charismatic person: he’d take product samples, get in the car, drive across Ukraine with price lists and brochures—and then people would call us. Later, I realized that renting trucks was unprofitable; it was better to take out a loan for our own lorries and deliver ourselves, ensuring the confectionery was stored correctly. Our lorries could leave at 3-4 AM right when the dough was ready. When we built the first workshop, to attract experienced workers, I came up with the idea to build a comfortable dormitory above it. In 2006, we patented new desserts: they were similar to cream puffs but shaped as rings. I personally enjoyed dipping cakes in chocolate, so I figured others might too.

How old were you and your husband when you started the business? Are you the same age?

Yes, the same age. We were a great team. We started at 17, and by 19, we were ordering lorries, and my husband built the first workshop with friends. At 20, we bought out the rented one.

What was the motivation for working so hard together with your husband? What was your dream or goal?

We essentially slaved for six years straight. No children, no travel—we hadn’t seen anything outside of work. We even slept in that dormitory because it’s a business that demands constant presence. We were very young, but we couldn’t afford ourselves a vacation. And then he said: “I’m so tired.” I replied: “I’m tired too.” He asked: “Do we have money?” I said: “No, not in the safe right now. I’ve ordered 10 tons of sugar and a new rotary oven from France. And we still need to pay off the loan for the first lorry…” “Is this a life?” He looked at me and suggested, “Let’s sell the business.”

Then we thought about what each of us wanted. Since childhood, my husband had dreamed of being a photographer. And I—a film director. We sold the business in 2009—a move that was financially unsuccessful by pure business standards, but entirely successful for us personally. And it continued to bring in passive income because we bought a few small shops. When you make tons of product to go somewhere like Kryvyi Rih, something is left over, and confectionery has a short shelf life, so it needs to be sold somewhere. That’s how the small shops emerged, which we had until 2017. We couldn’t sell them, so we partially rented them out.

You wrote 12 books on how to streamline all processes in the hotel and restaurant business. Did you come to this after selling your own business?

In 2011, my husband was diagnosed with cancer. There was no trust in Ukrainian medicine back then, so we traveled to Europe and private Israeli clinics. A year of treatment ate up all the money. Directing wasn’t providing enough funds to support a family and a sick husband. The business community in Kyiv invited me to give speeches several times. One day after a speech, HoReCa businessmen approached me with questions. That’s when I realized I could start consulting companies. I told them, “I’ll come tomorrow. How much are you willing to pay for a consultation?” It was a hotel complex: three restaurants, a hotel, and a park. I identified mistakes, created a checklist and a timeline. I identified mistakes, created a checklist and a timeline. I offered staff lectures to improve service and streamline their document flow. In 2012, I had 10 such contracts. I then decided it would be more efficient to write books and sell them during my speaking engagements. That’s how 12 books were written, based on real cases of business process optimization.

Directing

How did your directing career develop? When did you come to documentary films as your main format?

When we sold the business, my husband and I split the money in half, and each of us pursued our passion. He studied photography, opened a photo studio, and held exhibitions. And I went to study TV and film directing and had a child—just as I wanted. In 2010, my husband and I divorced, but we remained on friendly and close terms, continuing to resolve many matters together. My son grew up on set. I wasn’t the oldest in the class, but years in business set me apart with valuable experience. Oleksandr Muratov noticed me and invited to collaborate. I started working in directing in my very first year: I’d park the stroller; everyone would be shouting, filming, and carrying lights while my son slept.

I immediately knew I wanted to shoot advertisements and documentaries. Documentary filmmaking in Ukraine was not well-developed, weaker than its Russian counterpart. Even after the collapse of the USSR, Ukrainian documentary filmmaking often looked to Russia for guidance. Fortunately, I met people who wanted to popularize Ukrainian culture. That’s how a series of 12 episodes about Ukrainian medical institutes emerged. Then came films about our talented contemporaries whom almost no one knows: Petro Tronko, Anatoliy Lupynis, Serhiy Komisarenko, and Petro Fomin.

Did you ever think about moving to another country to live and film?

I’m from Donbas, from the city of Siversk, which was Russian-speaking. In the 1990s, when we were studying, there were virtually no Ukrainian books in school—and my grandmother and grandfather were the only ones who spoke Ukrainian with me. But every time I returned from abroad, I realized: for me, there is no better country than Ukraine.

I started traveling as a director. My husband and I were already divorced then, and I traveled with my son, specifically taking on projects that allowed me to explore the world. I lived in Spain for half a year, and in Tenerife, I filmed the volcanoes of the Canary Islands. I spent nine months working in Ecuador as a co-author of a Spanish-language documentary about the Mayans. I filmed with the Ukrainian diaspora in New York and did private advertising projects in Madrid and Valencia.

We made a major documentary film, “Giving chance to survive”, on which we worked for a year and a half with an incredible team. We brought relatives of the Germans who were involved in the Babyn Yar crimes to Ukraine, showed them the site, and organized a meeting with the Jewish children who survived. Not many of them are left. Everyone cried there. It was then that I discovered I had Jewish roots. I found my relatives in Israel and saw them when we presented the film there. After that, I had several more joint projects with Israel.

You traveled and filmed extensively abroad. Yet, at home, you filmed about prominent Ukrainians and showcased Ukraine. Was this a conscious choice of topic?

My son and I have traveled to 28 countries in total. But right before the COVID lockdown, I returned and felt: I am home, and I don’t want to go anywhere else. And then I realized I had shown my son the world, but he hadn’t seen much of Ukraine. We got in the car and drove across the entire country in three months, discovering the most beautiful places. That’s when the idea for the project “Travel for Ukraine” was born—to show that we have service and unique locations that are just as good; we just need to present them correctly and beautifully.

I was supported, and we received a grant. The program was scheduled to launch in March 2022, and we managed to film nine episodes. Due to the full-scale invasion, however, the project was never released. More than half of the filmed territories are now occupied and being destroyed by Russians.

There were six men on our team. Now one is in captivity, one went missing while delivering humanitarian aid. The others volunteered to join the army in 2022 and were killed almost immediately.

Previously, every good specialist in television and cinema was invited to work in Moscow. Were you invited too?

I had a bad experience with Russia. In 2016, our film “Giving chance to survive” about the tragedy of Jews in Babyn Yar was released. We invited historians as speakers and made a small parallel. At the end of the film, we showed footage from Maidan in 2014, leading to the point: don’t repeat history, so that tragedy is never repeated on Ukrainian territory. There isn’t even the word “Russia” in it. But in 2016, when I flew to Ecuador through Domodedovo Airport, I was taken off the plane. I had my child with me and a lot of equipment in my luggage. I was subjected to an 11-hour interrogation. My cameras were broken, and my memory cards were scattered around the room. I was afraid of Russian authorities after that: they didn’t beat or torture me, but the psychological pressure was very strong. And in 2022, Russia used our footage from this film and declared the entire film crew wanted. I flew to Australia with many transfers and was constantly afraid that I would see FSB officers in European countries, because Europe’s stance on the issue was unclear at the time.

Where did you meet the full-scale invasion, and how did you leave?

I persuaded my relatives to evacuate to Western Ukraine for at least two months and rented a house in Truskavets. At that time, [the French president Emmanuel] Macron spoke with Putin and Zelensky and announced that there would be no war. My parents calmed down and returned home to Eastern Ukraine.

On February 19, my son and I returned to Kyiv. But by February 25, a shell hit an apartment building on Koshytsia Street, leaving a huge hole in the middle of the complex. We lived right across the street. I got scared and decided to leave. We hit all the traffic jams. About 40 kilometers from the Krakovets border crossing, we abandoned the car: there was no petrol, nothing to refuel with, and a continuous traffic jam where people were standing for several days. We walked in the snow to the Polish border, people were abandoning suitcases along the way because they couldn’t carry them. My son and I saw this and only took two backpacks. The Poles closed the checkpoint for 11 hours, unable to receive people. A stampede began: snow, women, children, screaming, and crying. Local teenagers brought hot water and pies on bicycles for thousands of people. Completely unfamiliar people, to whom I gave the keys, later drove my car back to Kyiv to my sister.

My son’s rib was fractured in the crush—it was a large crack. He kept saying: “Mom, I can’t breathe.” A friend took us to Latvia. The doctor ordered him to rest. I hoped my son would recover, and we could go to Spain because I knew Spanish quite well.

But the producer of “Giving chance to survive” called and advised me to go as far as possible. Because Liepāja, where we stopped, is a port city on the Baltic Sea, where Russian military personnel lived. A colleague of mine lived in Australia and helped us open a tourist visa.

Was this your first time in Australia? What struck you as significantly different?

Yes, the first time. When I landed, I looked up and saw that the moon and stars in Australia appeared upside down. Australia is truly the edge of the world and unlike other countries. But this was no sightseeing trip. My son saw big beautiful parrots and said: “Before, we traveled, everything was interesting, but now I look at the parrot, and it annoys me. Mom, why am I not happy about anything here?” Or: “I hate Australia. We won’t stay here, their buses run badly. I want to go back to our Kharkivskyi District.”

The English language in Australia is very different. Even the British and Americans don’t understand Australians: people often speak with their mouths closed, shortening sentences and skipping sounds. It was difficult for me, but in 2022, I didn’t plan to live here: I just wanted to wait until my Russian “wanted” status was lifted. The film’s producer filed a case in the international court, seeking the entire film crew of “Giving Chance to Survive” to be cleared and removed from the wanted list. On March 26, 2023, the hearing took place, and we were removed.

What was the most difficult thing for you in Australia?

I knew almost nothing about the country. In some regions, it snows in winter, and people ski. And in the warm states, there is no winter at all. Australia is very large, so it’s diverse. We arrived during La Niña—a period of rainfall. It rained every day. Everything was moldy, and our clothes didn’t dry, remaining damp. My child developed an allergy to this dampness and mold: he coughed constantly and hardly slept. I didn’t realize then that we had flown in during winter and settled in an area with more rainfall.

Kateryna’s own video production in Australia

When did you decide that you would, after all, live in Sydney and build a business here?

In 2023, I left my son here, arranged a power of attorney through a lawyer, and went to Ukraine due to family difficulties. I stayed there for half a year. I was so angry about all the war’s losses that I wanted to go to the front line and film everything, disregarding my safety, my motherhood, or the fact that my only child was at the edge of the world. I volunteered and helped with filming. I went spontaneously: I agreed in the evening, and by morning, I was heading toward the Bakhmut area.

Our region is gone; many children have been forcibly removed from Kherson, Mariupol, and Eastern Ukraine. I know families whose children are now in Russia, while the parents are alive in Ukraine. After seeing the frontline, talking to the military, and traveling with volunteers, I returned to Australia. I remember walking up to the ocean and feeling an overwhelming sense of peace: I am safe, and so is my child. Now I look at Australia differently. Here, I received a Global Talent Visa—a permanent visa with only 50 issued per year across different industries.

How did the idea to create a video production company in Australia come about?

When I realized I was returning to Australia, I wondered: what will I do there with my English? I had already worked for two studios, but they paid peanuts. Then I decided: I need to start my own business.

While still in Ukraine, I made an Australian website and printed business cards. On the plane, I compiled a table: analyzing the target audience, and who to focus on. Wedding filming was immediately dismissed—people here don’t tend to spend much money on it. Filming people also didn’t make sense because the market is heavily undercut by immigrants and students. But large companies that order educational videos seemed the most promising. With them, I could rely on written English correspondence instead of speaking, and they provided the best ratio of profit to time spent.

I prepared beautiful commercial proposals for them. I arrived in December, and by January, everyone here was on summer holiday. But by February, I had three contracts.

What were your first orders in Australia, and what are they now?

My very first order here in 2022 was for 3,500 AUD, and I was very nervous. It was a project for the New South Wales government, the Digital Help for Refugees department. I needed to create a series of animations for refugees about Australian laws and taxes. (Generally, talking about personal finances is not common in Australia.)

Now I have companies with whom we have signed contracts: I fully provide them with video and photo content, which brings in stable income. I have expanded my team through outsourcing: now I work with 5-6 people, whereas a year ago, it was only 2-3. Prices for video and photo services are quite low in Australia, rent is high, and there is a lack of expectation for high-quality service. The hardest thing when signing the first contracts was to prove to them that ordering high quality is profitable.

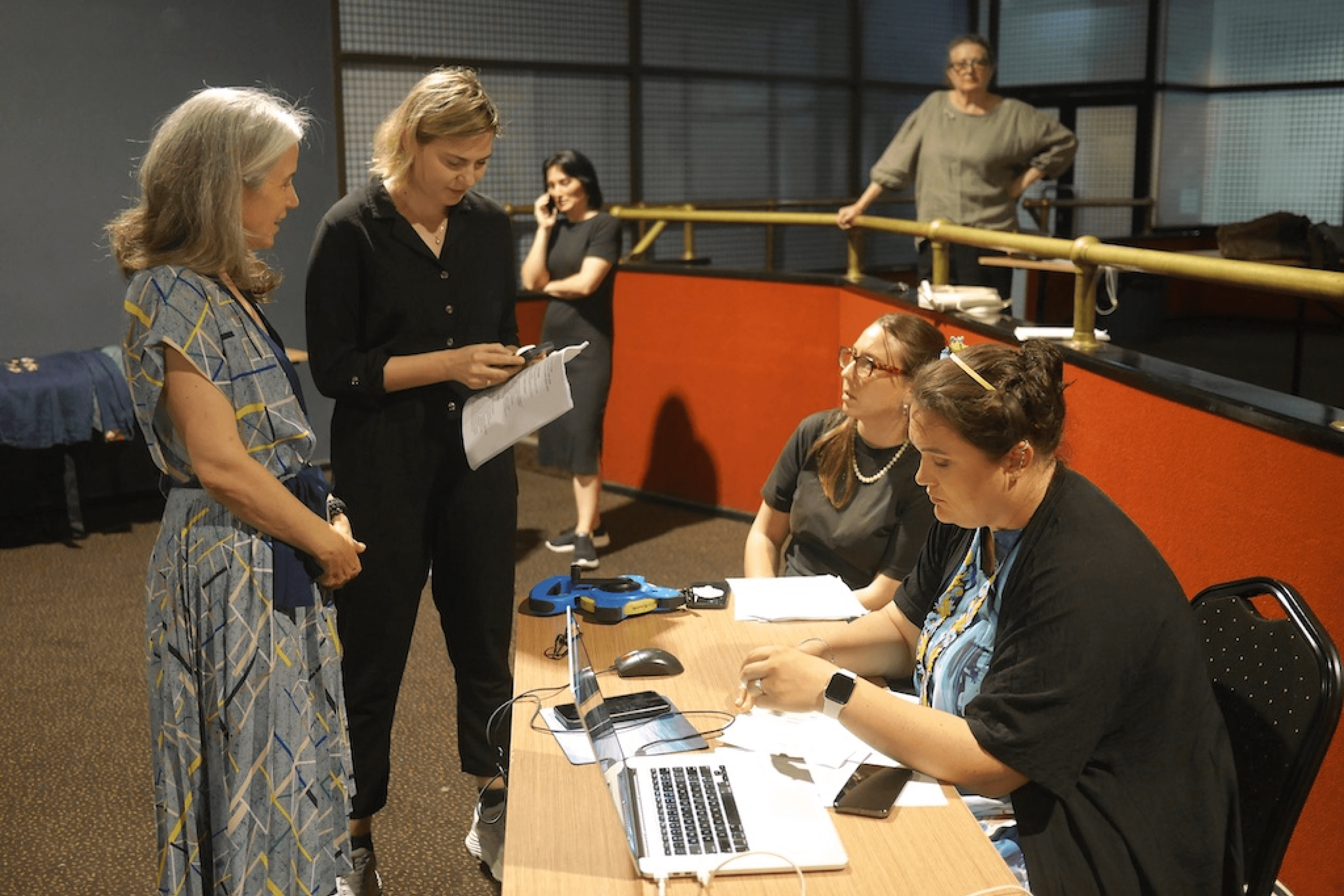

The first order for my production company was for SBTA—a training company in the center of Sydney where accountants, managers, and hotel business workers study. Previously, when I worked for two studios, I was contracted to make educational videos for the state of New South Wales—I had already collaborated with SBTA. Then, this company was the first to sign a contract with me.

Who are your colleagues? Ukrainians or locals?

I work on an outsourcing basis, involving guys and girls from Ukraine. I know them well; they perform the work quickly and with high quality, and Australian clients really like this. Everything happens slowly here, and the favorite phrase is “no worries”: it can even take three months to set up an internet connection.

I know how to do all stages of production myself, so I can control the quality of the services. I know how to film—I took courses. I do editing in all major programs (Premiere, DaVinci, Final Cut) and create animation in After Effects.

How much money was needed to open a production company in Australia? And how difficult is it from a bureaucratic and accounting point of view?

No starting capital was needed at all. If you know how to do everything, you can start from scratch. I built the website myself, designed the business cards myself. I rented equipment here—using the deposit I received from orders. The only regular expenses are for the software, which I pay for annually.

Opening an equivalent of a Ukrainian sole proprietorship here can even be done from a phone. I handle my own accounting and file declarations. Only the first month did I call the hotline for a free consultation.

What are the taxes in Australia now?

The rates depend on the state and your business turnover. I currently have a higher turnover—I’ve filmed in Tasmania, Melbourne, Queensland, and Canberra. But simultaneously, the profit is lower because the tax rates are higher. If the annual turnover is up to 20,000 AUD, you don’t pay tax. If it’s from 20,000 to 80,000 AUD—you have to pay 18%. From 80,000 to 120,000 AUD the tax is 35%. Over 120,000 AUD—42%.

Australia is quite an expensive country. And medicine is very expensive. There is the Medicaresystem here, but if you work, it covers almost nothing. You have to pay for everything and secure your own private health insurance in advance. Failure to do so can result in substantial additional costs in the first year. And I had cancer; I completed my treatment in Australia. Thank God my child has an inexpensive insurance policy. Because I had to pay for my own for six years at once.

How many documentary films have you directed in total?

I have participated in various working roles in 26 short and feature-length documentaries since 2010.

Which projects give you the most satisfaction?

I have very high self-criticism. I never re-watch my own work because I immediately see what else could be improved, and that bothers me. Although people like them—some even cry, as was the case with the documentary for the UN.

I worked on several projects with the Office of the President of Ukraine that gained attention in 2022–2023, and also had a joint project with the First Lady, Olena Zelenska, in 2022.

So, what is the indicator of success for your documentary film?

Its impact—whether it helped achieve its goal or not. Now I essentially make documentaries on a volunteer basis. In Australia, money is often raised to help Ukraine. I always clarify: what exactly is the goal? For example, events in Australian Rotary clubs to support Ukraine, or a local Ukrainian charity organization wanting to raise funds, or in 2023, I made a video to help orphanages in Kherson. And depending on the topic and needs, I determine what kind of video to create to ensure the goal is achieved. In 2024, I did 2-3 large volunteer projects a month. Now I do one a month.

How is Ukraine currently viewed in Australia?

In Canberra, I met in the office with the head of a company I will be collaborating with starting in 2026. We touched on the topic of Ukraine, and he said: “My grandparents are immigrants from Britain. I was born in Australia, have lived here all my life, and am only interested in Australia.” For him, what is happening in Europe, not even just in Ukraine, is distant and uninteresting. This position is quite common here.

So, the feeling of the presence of Ukrainians and the reality of Russia’s war against Ukraine is not felt in Australia due to its remoteness?

Australia is a country where you have to speak loudly to be heard. And the Ukrainian diaspora does this. Approximately 11,000 Ukrainians arrived here in 2022–2023, with about 7,000 more following later. For effective communication with the government, it’s crucial that the diaspora remains united. Kateryna Argyrou from the Ukrainian initiative Defend Ukraine Appeal tries to bring everyone together. We also have a very active ambassador, Vasyl Myroshnychenko. He helps every Ukrainian project: spreading information, inviting diplomats, providing reports to the Australian government.

And the Australian government heard us: Ukrainians who arrived in 2022-2023 and had not received protection in other countries now have permanent resident status here. This is a great achievement. Moreover, the years of stay are counted: those who arrived in 2022 and who haven’t violated the visa conditions will be able to receive citizenship in just one year. This was possible thanks to the work of volunteers: they collected statistics showing that almost all Ukrainians have higher education, are not on social assistance (Centrelink), and only a small percentage used financial support—mostly pensioners or mothers with many children, but even they worked part-time.

I helped with presentations, meetings were held with the Department for Immigration and Citizenship, and we achieved a result. This success was clinched by a personal story: the woman involved in advocacy has a very capable daughter who participates in state projects and has excellent English. She was invited to a meeting with the Minister. She was graduating from school, but universities wouldn’t accept her because she didn’t have a permanent visa.

How do film events in Australia differ from European and American ones? And is there a place there to represent Ukraine?

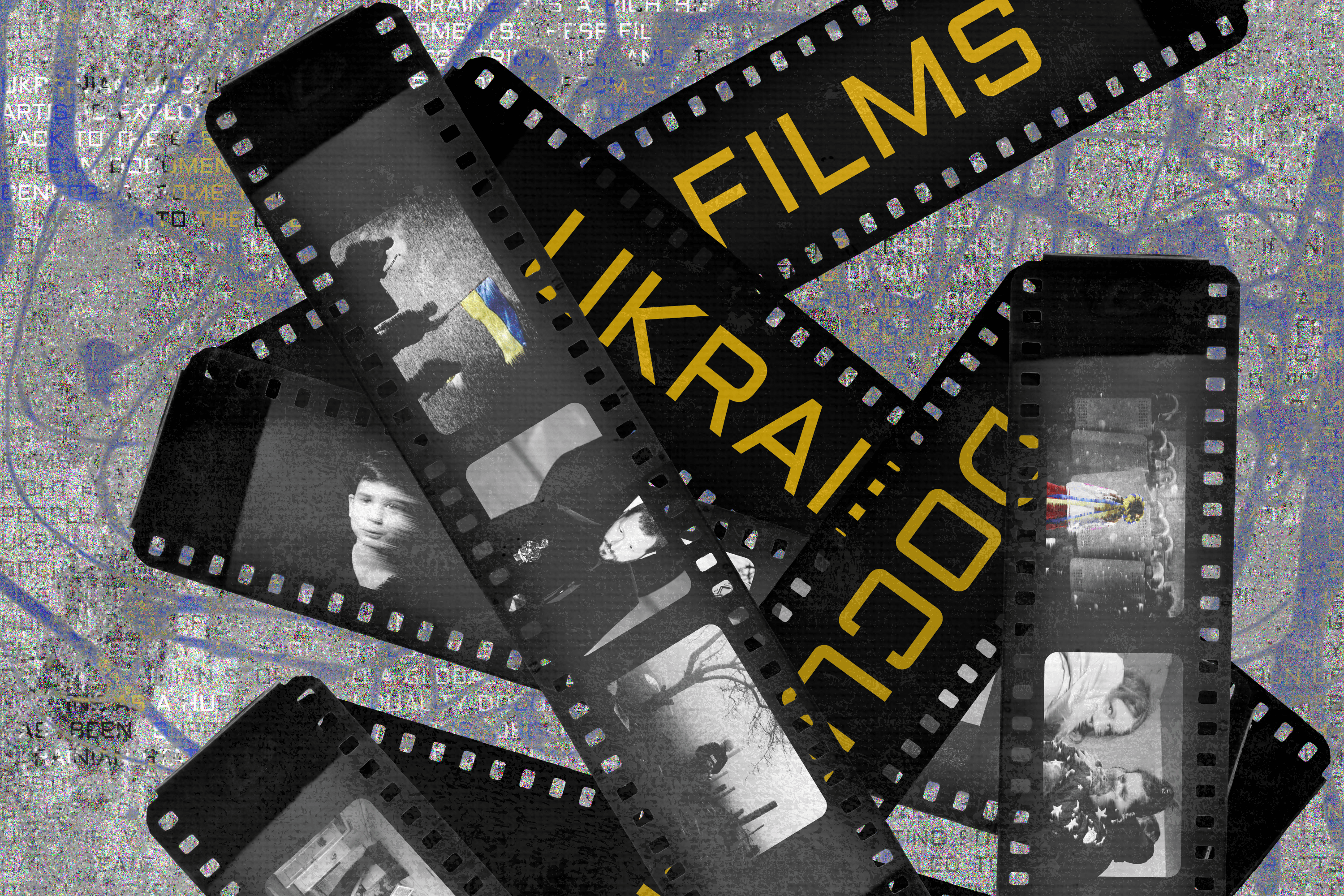

There are films from Ukraine that are well-received here too. Now, Ukrainian movies are regularly shown in Australia—and people happily attend. There is a culture of festival cinema here, even more developed than in Ukraine: audiences are used to frequenting cinemas.

I’m glad I had the opportunity to organize the Ukrainian Film Festival in 2023—a first for Australia, where we sold out all the tickets. We did everything at our own expense, and all the money from the tickets went to the Ukrainian film fund. Today, Ukrainian films are also appearing on large platforms: for example, in 2022, the Antenna Film Festival—the largest documentary film festival in Australia—didn’t want to take Ukrainian films but showed Russian and Polish ones. And now, there is always a Ukrainian film in the program, and we even managed to ensure that Russian films are not shown; I spoke on Australian radio to advocate for this. We are planning to hold the Ukrainian Film Festival in Australia again in 2027.

Of course, there are difficulties. The formats here are different from Europe, Ukraine, or America: all feature-length films needed to be converted to digital format, which wasn’t easy. Furthermore, in 2022, there were almost no Ukrainian films with English subtitles. So, I had to do the translations and subtitles myself, working with a volunteer. Dubbing is too expensive: in Ukraine, they wanted $9,000 for one film, even with a discount. But I’m glad that this process gave an impetus: now Ukrainian films are brought to Australia regularly; they run in cinemas about twice a month. Viewers come, and a circle of fans is forming.

Do you have your own ambition regarding Ukrainian-Australian cultural diplomacy?

Ukrainian cuisine needs to be popularized. Once every three months, we organize events for both Ukrainians and Australians. For example, we did Heartland of Ukraine—an evening of contemporary Ukrainian poetry by Serhiy Zhadan and Victoria Amelina, where I was responsible for the video accompaniment.

I dream that the Ukrainian language will become available in Australian schools as a second foreign language, so our children can choose it. It is also important to bring exhibitions of Ukrainian artists so that the culture becomes recognizable. Sports events at the state level are no less significant: for Ukrainian athletes to come here. For example, we have already invited a rugby team.

Another direction is the Ukrainian business. It’s gradually appearing here; you can already find our fruit snacks with a drawn snail in Coles supermarkets.

Are you referring to the Bob Snail brand? We previously had an interview with the CEO of its Canadian representation—Dmytro Shuhayev.

Yes, that brand. We have products that will succeed in Australia: Ukrainian production of shoes and bags is of quite high quality. Australians appreciate quality but don’t chase brands like in the US. The local market has many Chinese goods that people are already tired of, and domestic production doesn’t fill this niche. Therefore, Ukrainian leather products have good prospects.

I also see potential in cooperation in the agricultural sector. Australia grows the same crops as Ukraine, so leveraging their experience for the restoration of our agricultural lands after the war would be very valuable. Everything there is highly automated and systematized; we have much to learn.

A separate direction is educational exchanges. In the future, when there is no war in Ukraine, Australian-Ukrainian exchange programs for students and teachers can be implemented. I know that similar exchange projects in the field of psychology already exist, and this is a good example for other sectors.

What topics do you aspire to create films about?

My most painful topic right now is children. I want to make a film about incredibly brave children. There are many interviews and broadcasts about those who lost a leg due to the war but continue to play sports, or about a boy with a burnt face who dances, or a girl from Kramatorsk who runs again. But there are no documentary films about them. I would combine these stories into one film in English, because we know and see them in Ukrainian media, but the English-speaking audience doesn’t. There are many such children, and more than one film is needed. For example, about the boy who became the guardian of his brothers after his mother died in the Kherson region. Their stories need to be shown to the world because the English-speaking audience values examples of strength of spirit when a person overcomes incredible difficulties. And here we are talking about children from whom there is much to learn.