In April 2022, language activists Ivanna Kobieleva and Natalka Fedechko, along with entrepreneur Ivan Kapeliushnyk, launched the National Initiative Yedyni (United— a network of free Ukrainian language courses that have helped over 140,000 people in Ukraine and abroad learn and switch to the Ukrainian language. Since its inception, hundreds of volunteer moderators—who are professional Ukrainian philologists—have hosted over 8,000 in-person conversation club meetings across 38 communities in Ukraine, 12 cities abroad, and online.

The Yedyni team also conducts regular webinars and continuously recruits new ambassadors each month. To date, over 80 opinion leaders, including TV hosts, athletes, military personnel, writers, and singers, have joined the initiative. Halyna Shcherba moved to France following the full-scale invasion. In 2023, she became a moderator for the Yedyni сonversation club in Nancy, where she leads meetings every Saturday.

In an episode of the YBBP podcast I’m Just Asking! Halyna shares her experiences with cultural diplomacy through the Ukrainian language club in France. She emphasizes the importance of building horizontal connections within the local community and discusses the profound emotional topics that often bring people to tears—tears of relief. You can listen to the episode here. Below is a summary of the conversation.

I was a volunteer, and I kept thinking how great it would be to bring Ukrainians together. I had heard stories — many Ukrainian women had arrived with their children and relatives, and it was often the older women who suffered the most. They felt isolated and alone. One day, in one of the group chats, I saw a message asking whether there were any philologists in the group. It was written by Yevheniia, who had come to France with her child and her mother. Her mother wanted to switch to Ukrainian so her grandson wouldn’t hear the Russian language, but she needed practice and support in a foreign country. That’s when Yevheniia came up with the idea of starting a Ukrainian conversation club. She began looking for someone who could lead it as a moderator. I immediately connected with the idea and signed up for the Yedyni moderator training. While I was going through the training, Yevheniia started searching for a venue.

Nancy is about two hours away from the small town where I live, so I wasn’t able to handle the organizational side of things. Yevheniia took full responsibility for that. At first, we couldn’t find a space — everything was either too expensive or unavailable, like the public library. So, we decided to start meeting in a café. We shared an announcement in a local Ukrainian community group in France and set up a registration form to gauge interest and see if anyone would actually show up. The response made it clear that Ukrainians in France had a strong need for the Ukrainian language during the full-scale invasion. Later, representatives of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church got in touch with Yevheniia — the local parish had access to a space, and as it turned out, it was available on Saturdays at exactly the time we needed for our meetings.

I’m incredibly happy that the Ukrainian conversation club has brought so many people together and helped them become friends. There is a Ukrainian community in Nancy, but it’s a fairly large city, so many of them didn’t know each other at all. Eventually, the women started forming bonds — they began visiting each other for borscht or pies. If someone got sick, others came to check on them. Older people helped young mothers with childcare, and younger people helped the elderly with hospital visits and translated for them in French. Horizontal connections started to form. And the spark for all of this was our Ukrainian conversation club. I believe we truly achieved our goal. As word about our club got around, neighbours started bringing their neighbours, and people travelled in from other towns.

I’ve spent my whole life working in the media and entertainment field, always trying to find something positive to share with others — morning shows, uplifting stories, anything with light in it. But after the full-scale invasion began, I cried like I never had before. At one point, I told myself, “Enough. Stop crying. We have to act. Our grandmothers survived World War II — and we will survive this too.” So I began doing whatever I could to keep going. And this club — it’s not because I see myself as some ambassador of the Ukrainian language. Honestly, I do it for myself as well. I show up, put my own worries aside, and simply try to be of help.

The first meetings of the club felt more like group therapy sessions. Each time, a new person would join, and it would always begin with tears. She’d share her story, break down, and the whole group would cry with her — only then could we begin. For many women, even smiling felt impossible. To get a real conversation going, you have to be deeply empathetic — open and present — so the person can feel safe enough to open up. I tried to structure our meetings in a way that would allow for that human connection. First, I had to reintroduce people to each other — people who were hurt, anxious, grieving — and only then bring them together. Our conversation club became a small piece of life that helps people recover emotionally, come together, and support one another — and themselves. It gave us all permission to keep living. We are strong because we are united.

At first, I tried to stick strictly to the curriculum, to cram all the material into a single session. But now I respond to the moment — just like I used to during live broadcasts. Some days, I have a talkative group — so we talk. Other days, they want to sing — so we sing. You have to come up with something fresh on the fly, so people stay engaged and want to come back next time. Still, our base was always the materials from the Yedyni movement.

There’s one story that beautifully illustrates the power of family connections. After just our very first meeting, a young woman felt so inspired that she began researching her family tree. She remembered having a distant relative — a woman who had emigrated long ago, written a book, worked at a museum, and now lived in Paris. She started searching and actually found her aunt. They arranged to meet in Paris.

The educational side of the club plays an important role as well. We revisit vocabulary — everything from the names of flowers to household items and bedding. Our themes often revolve around Ukrainian traditions and culture, where even the smallest detail can reveal something meaningful. Even everyday words can surprise people, because there’s so much they simply never had the chance to learn. I include links to programs, documentaries, and books I use while preparing sessions. People from different regions of Ukraine also share their own knowledge. We even have a tradition of singing together at the end of each session. Each person remembers the same song a little differently — and in singing together, we bring its variations to life.

When people register for the club, we ask what they’re interested in and why they decided to join. Some were drawn to literary readings, others preferred interactive formats — but all of them wanted to learn more about Ukrainian culture and traditions. We formed a Telegram group named Ukrainian Conversation Club and have been adding everyone who joined. I run the channel myself — I’m used to working with information, and I love sharing the little gems I come across.

We’ve even organized film screenings with a director present. When my colleagues at Suspilne (Ukraine’s national public broadcaster) produced a powerful documentary — one I had the chance to edit — I dreamed of bringing it to France. And we actually made it happen: we managed to bring over both the director and the editor, which felt like a miracle, and organized a small screening tour across Lorraine. But it all began with the Ukrainian conversation club.

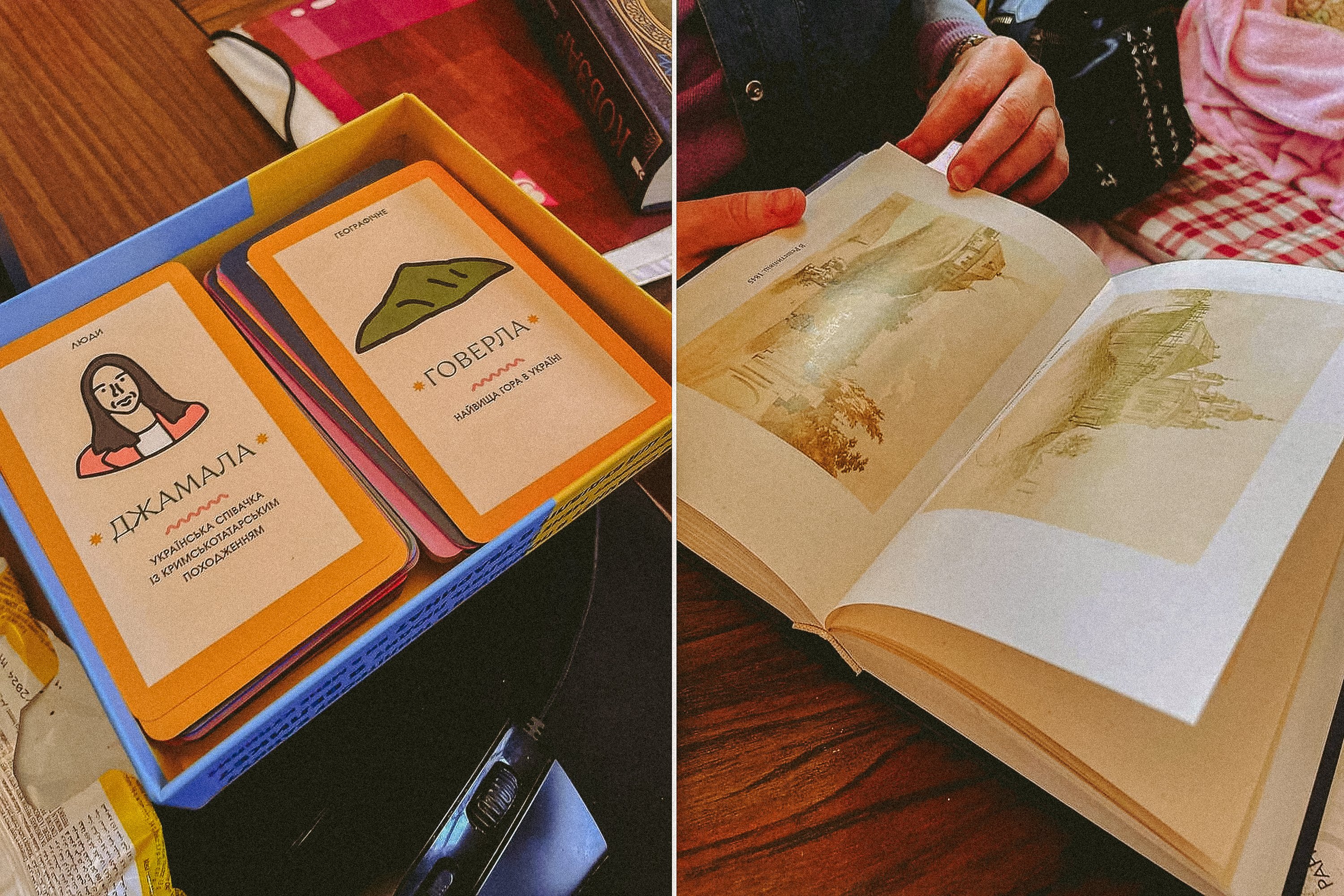

If you want to do something like this well, you need the right resources. A projector to screen documentaries. Board games from Ukraine for language-based activities. A copy of Shevchenko’s book for his birthday. And you need a dedicated person to manage it all — because it’s impossible to keep everything running smoothly on your own.

Before 2022, Ukrainians in France would often gather in so-called «Pushkin Clubs.» And this isn’t just a French phenomenon — it’s a common pattern across many countries. Russia has long invested heavily in promoting its language and culture. It’s part of that slow, creeping hybrid war: if their athletes aren’t allowed at the Olympics, they’ll offer ballet instead. Nancy had a Pushkin Club too. Our Ukrainian conversation club became one of the first real alternatives. Today, if you open the local Ukrainian community chat in Nancy, you’ll see a long list of weekend activities: the Ukrainian conversation club, a Ukrainian school for children, creative workshops, sessions with psychologists, an economic club, networking forums, computer classes, a French-language conversation club for Ukrainians, yoga, film screenings, and concerts by Ukrainian artists — from bands like Tin Sontsya to singers like Oksana Bilozir. All of this is organized by Ukrainians, for Ukrainians.

The Ukrainian conversation club also serves as a form of cultural diplomacy. Russian groups in Nancy have tried organizing their own demonstrations. At one point, the city hall raised a Russian flag for Victory Day (marking the end of World War II). Ukrainians responded: “What’s going on here?” The city explained that they display flags of all participating countries. But why just the Russian flag? Why not the Soviet flag, which represented 15 republics, or the individual flags of all those countries that fought? No, it was only the Russian flag. The Ukrainian community came together and started writing letters. That tradition has since ended.

Our very first workshop was focused on preparing for a demonstration. We made symbolic blue-and-yellow heart-shaped pins that Ukrainians could recognize each other by in a crowd, and which we also handed out to the French. Even now, I still see people wearing them. They’ve held onto them. We also made traditional paper cutouts, taught folk songs, and hosted culinary gatherings where we shared Ukrainian dishes with the French. For Ukraine’s Independence Day, the city of Nancy gave us access to a hall for an entire week. The Ukrainian community filled it with activities: exhibitions, film screenings, and a literary evening hosted by the Ukrainian student group Halasvita.

What’s the hardest part? Every time, I worry that no one will show up. You constantly need to keep promoting it in order for it to grow. That takes hands — and ideally, some funding too. It would be great to have grants for clubs like this. But we don’t have that. Everything is run solely by volunteers, built on pure enthusiasm.

I’m truly happy that our community continues to grow — that people are coming together, staying active, and holding on to their identity even while living abroad. No matter what language they speak — even if they speak French — they still represent Ukraine.

Vytynanky are a traditional Ukrainian art form: intricate designs cut from white or coloured paper to create decorative silhouettes and ornaments for the home. You can read more about modern vytynanka art in our interview…

Haiivky are ancient ritual spring songs, traditionally sung to mark the beginning of spring and the start of the sowing season. In Ukrainian folklore studies, they are often referred to more broadly as vesnianky.