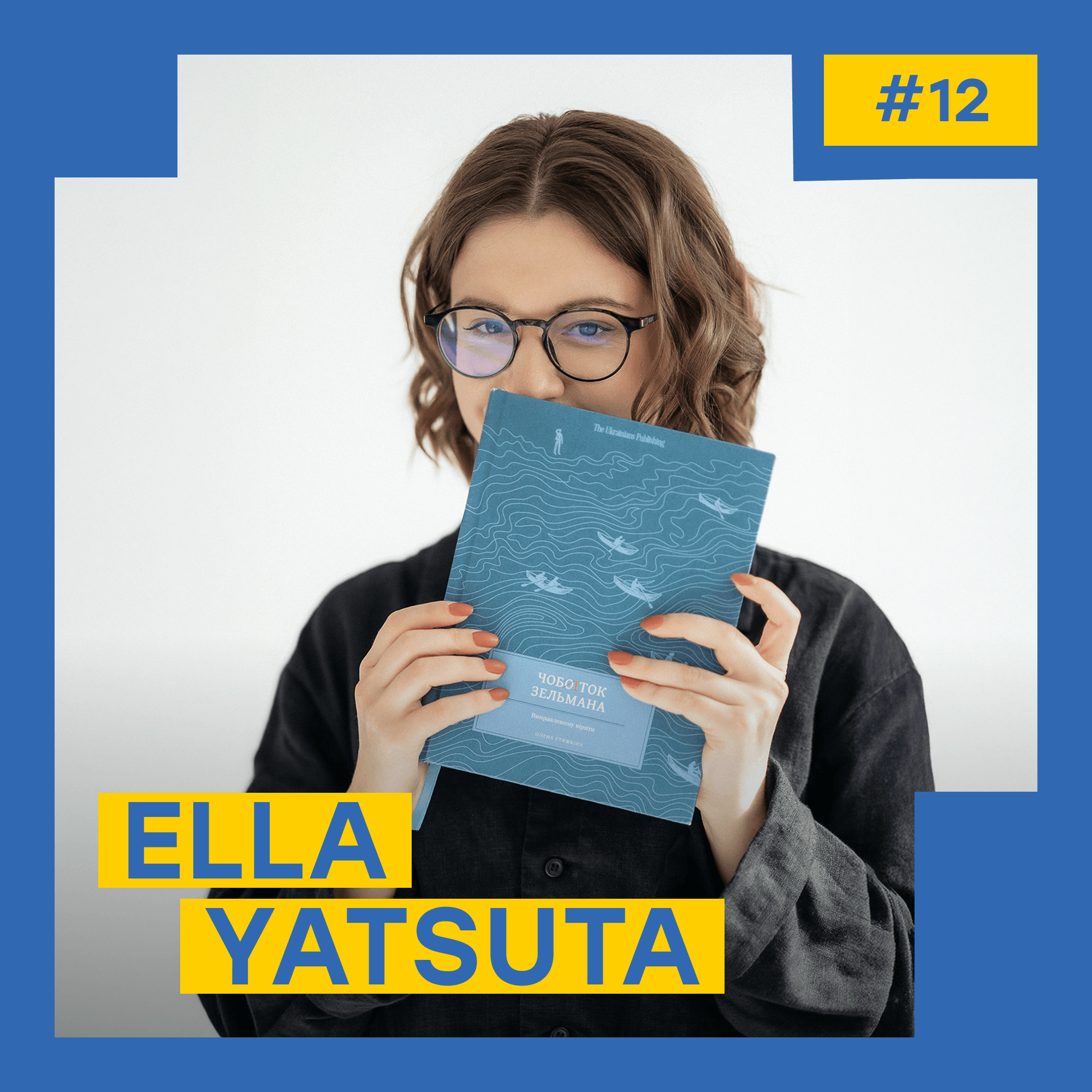

Ella Yatsuta is from Lutsk; co-founder of the Frontera Literary Platform, and CEO the Algorytm NGO.

In the I’m Just Asking! podcast, we asked Ella how to promote Ukrainian literature abroad and what specialists are missing for this, how book publishing has changed after 2022, and which Ukrainian writers are currently popular in the world. This is a brief summary of the conversation; the full podcast episode in Ukrainian is available here.

I’m a great patriot of my city and region. I manage the Frontera and Algorytm NGO platforms, which strive to make Lutsk visible to Ukraine and the world, so that people can fulfill their dreams there. We manage to make the city visible through literature: we have already held the Frontera festival six times in the Okolny Castle, attracting guests from all over Ukraine and abroad. At the festival, we organize a tour of Lutsk for media professionals, writers, and diplomats: to the Abo Abo creative hub, the Luchanka garment factory, and the Korsaks’ Museum of Contemporary Ukrainian Art.

We show foreigners that a Ukrainian product should not be treated with pity. Despite the war, everything is done at a high level. We create a competitive product in music, literature, and events. Media professionals and writers from other countries visit and later write in the press and on social media that they are surprised by how powerfully and uniquely Ukraine can present itself, and how interesting and undiscovered it still is. When an article about the Lutsk theater GaRmYdEr, which is over 20 years old, appeared in a popular Portuguese newspaper after the festival, we considered it our achievement.

The Frontera Literary Platform appeared in 2013, long before the festival. I was a second-year student living with my roommates in a dormitory. We complained a lot that in the small towns we came from to study in Lutsk, there were no bookstores, and writers did not visit our towns, nor did they come to Lutsk. The coolest events happened in Kyiv and Lviv. In 2013, we went to the Publishers' Forum for the first time and saw queues for autographs and writers walking the streets of Lviv, sitting in cafes—alive, not just from textbooks. I remember how we, with our knees trembling, approached Lyubko Deresh—he had a new book out then—and invited him to come to Lutsk. He wrote down the phone number of his literary agent and said his fee was ₴1,000. At that time, our increased stipend was ₴700 per month. We immediately decided: we would create events the whole city could attend.

From the start, we invited top authors. Serhiy Zhadan, Oksana Zabuzhko, Andriy Lyubka. We simply wrote letters to them; no one warned us that it wasn’t done that way. And it worked. The more great names we had on the list who visited and gave good feedback, the easier it was to negotiate with the next ones. Our team expanded quickly. We had no connections or any support, but in five years, we held the first festival. It was madness: we did it without experience in working with the city budget or negotiating with embassies. It seemed to us that a year ahead was a huge amount of time. Now we know that in a year, everything should already be ready.

In 2013, the word “fundraising” was unclear. We learned to write grant applications, organized into an NGO, and began to get to know businesses. And they said: “Your eyes are glowing, you’re doing something good, we will help”. Now it sounds like a success story. But there were moments of despair when we said: “Never again”. Today, 12 people work in the team, implementing all the projects. For the Frontera festival, we invite volunteers: 50 people every year, from schoolchildren to the elderly. Most projects are implemented with other NGOs or businesses.

Since 2013, a strong reading community has formed in Lutsk. The “reading virus” is penetrating the city more actively: there are bookshelves in cafes, beauty salons, and shops. For a classic reading club, where a book is chosen and everyone reads and discusses it, 40–60 people come every time. We run a gastro-literary club together with misto.cafe, which directs 80% of its profit to support public initiatives in the city. We invite an author and talk about the book. People buy a ticket, come, and eat what is mentioned in that book. For the last event, tickets sold out in three hours: it was a meeting with Dmytro Kuleba, the former Minister of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine. He published the book “Wartime Diplomatic Cuisine”. We ate dishes like those at diplomatic receptions; people loved it immensely.

It’s important for Ukraine to be visible abroad. For this, as many Ukrainian books in translation as possible are needed. Therefore, we are currently moving into the Romance-language world, started working very actively in Spain, and for two years, we have been co-organizers of the Ukrainian stand at the largest professional fair of the Spanish-speaking market—LIBER in Barcelona and Madrid. This is where publishers can meet colleagues and agents and exchange rights for books. It is also where it’s most likely to pitch a text by Ukrainian authors so that it is published in Spanish. And this language is one of the most widespread in the world.

We ordered a study of Ukraine in the Spanish-speaking world: book analyst Inna Bilonozhko studied which authors are published, in what circulation, and what is read better. To promote Ukrainian books abroad, such analytics are critically lacking. We realized that Ukraine works very little with this; our publishers don’t know this market and don’t know what to offer. We need to grow translators; there is a shortage of them. Previously, translations were mostly made not from Ukrainian, but from Russian, and from Spanish into Russian. Recently, Chytomo launched the Chapter Ukraine platform, which collects information about translations of Ukrainian books into other languages. Generally, if a book appears in an English-speaking environment, it is likely to be translated into other languages. Spaniards are interested in Ukrainian texts, but they are not familiar with them. To Spain, we submitted authors upon the request of publishers: they were interested in children’s literature, the theme of the war in Ukraine, and visually beautiful books from Ukraїner and the Rodovid publishing house.

There is no niche where there are enough translations from Ukrainian. We need to translate both the classics and the authors popular today. And genre literature, because it is great here and could provide good stories for Netflix. Ukrainian poetry is very strong; the war gave a push to its new round. More and more biographical texts and documentaries are appearing; these need to be translated to explain what Ukraine is about. In none of these directions, in any language, has a basic pool of texts been translated yet.

There are a dozen Ukrainian authors published in most countries. At a fair in Poland, a lecture by Bohdana Neborak on Ukrainian poetry was popular. Polish publishers attended it—several new Ukrainian books are already being prepared for publication. Previously, the Polish market mostly featured the same names as everywhere else: Oksana Zabuzhko, Serhiy Zhadan, Andriy Kurkov, and Tamara Horikha Zernya after the success of her novel “Dotsya”.

An author’s popularity in other countries primarily depends on the literary agent. What made Andriy Kurkov popular throughout Europe? The fact that he has a great agent who negotiated with key publishers working for several countries at once. That’s why you see Kurkov everywhere. The same story applies to Yurii Andrukhovych and Oksana Zabuzhko. Breaking through the first few translations always needs effort, and then things will move forward.

The profession of a literary agent in Ukraine is only just forming. How to gain experience to become one? In fact, you can’t learn this anywhere; there is no little book with contacts you can start from. You must build everything yourself, and you need starting capital to travel to different countries and establish connections. On the other hand, the financial side of this issue is difficult: Ukrainian authors receive ridiculous royalties that you cannot live on. And an agent’s compensation is a percentage of the author’s royalties. However, Forbes recently had an article about Ukrainian millionaire writers, although this is still a pleasant exception.

Personal contacts are the major work of every author. Yuliya Ilyukha’s novel “My Women” is moving well; she is working actively to have her books translated and is announcing more and more new translations. Andriy Lyubka is being actively translated because, as a Balkanist, he has a huge number of contacts in Balkan countries, has traveled there numerous times, performed, and is familiar with publishers and translators. The number of mentions in the media and performances at foreign festivals matters. It helps promotion when Hollywood actors read Ukrainian authors.

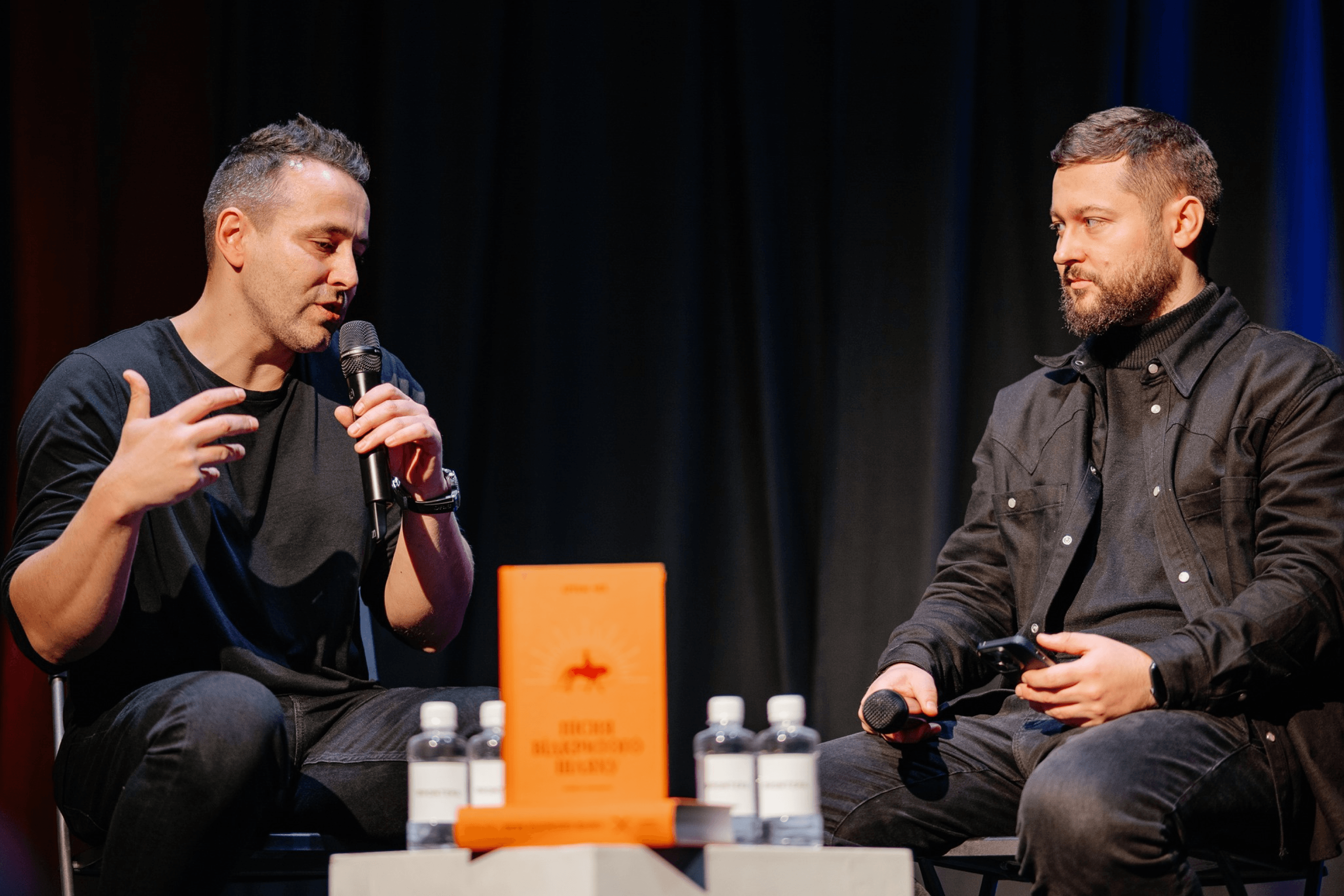

Ukrainians need to be more present at international events. The main thing is for our authors abroad to perform not only for the Ukrainian audience. Most translations are built on the “warm” contacts of those who stubbornly go to some fairs every year. We lack literary agents who have the skills to sell books and negotiate. Our team arranges for Ukrainian authors to perform on the same stage as authors who are popular today in Spain, France, or Germany. This is done so that those who don’t know the Ukrainian author come for their own and hear us as well. Now the situation is better than before, because after 2022, the world wanted to know what kind of people these are who held back Russian aggression and did not fall in three days. And there is an interest in reading about Ukrainians.

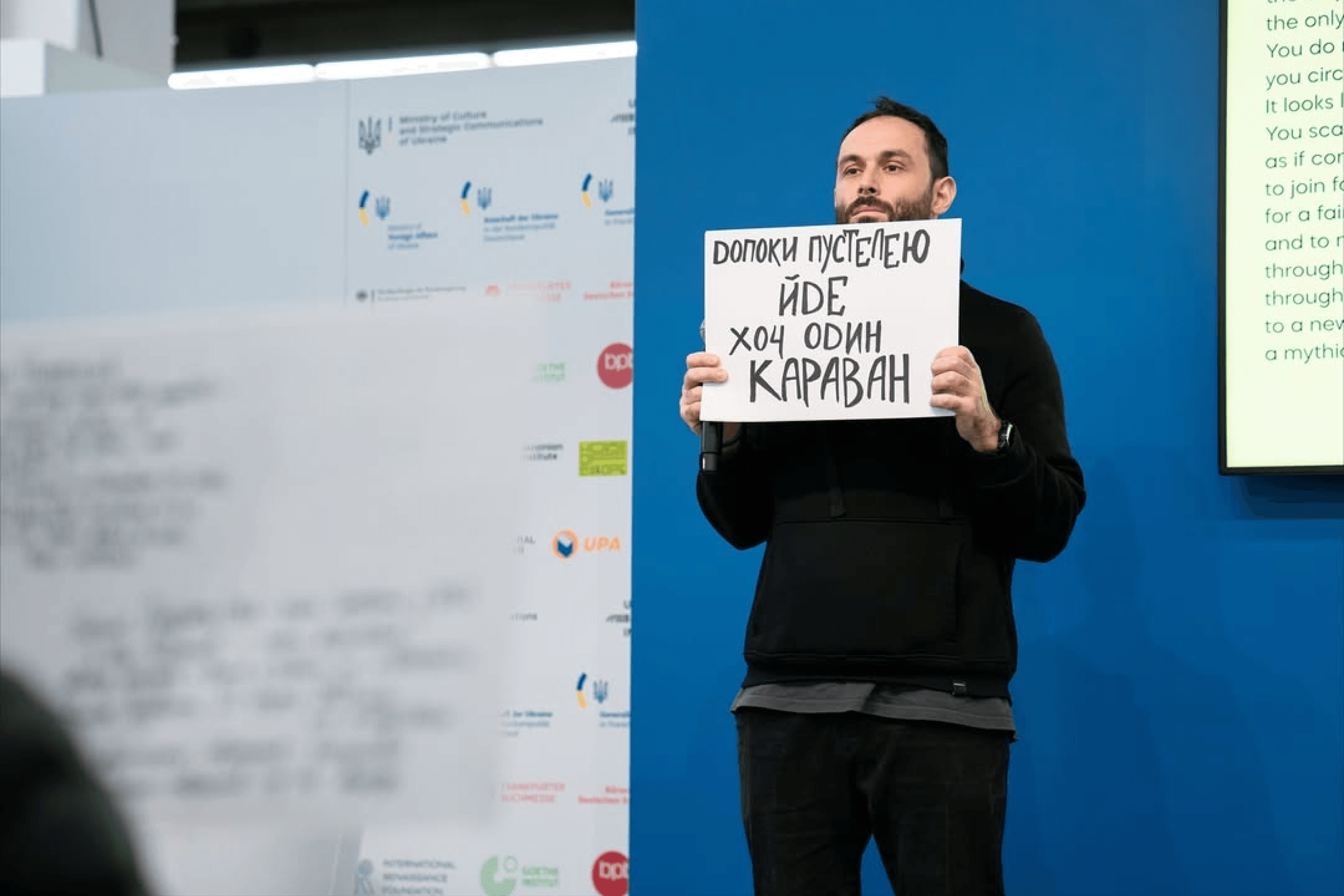

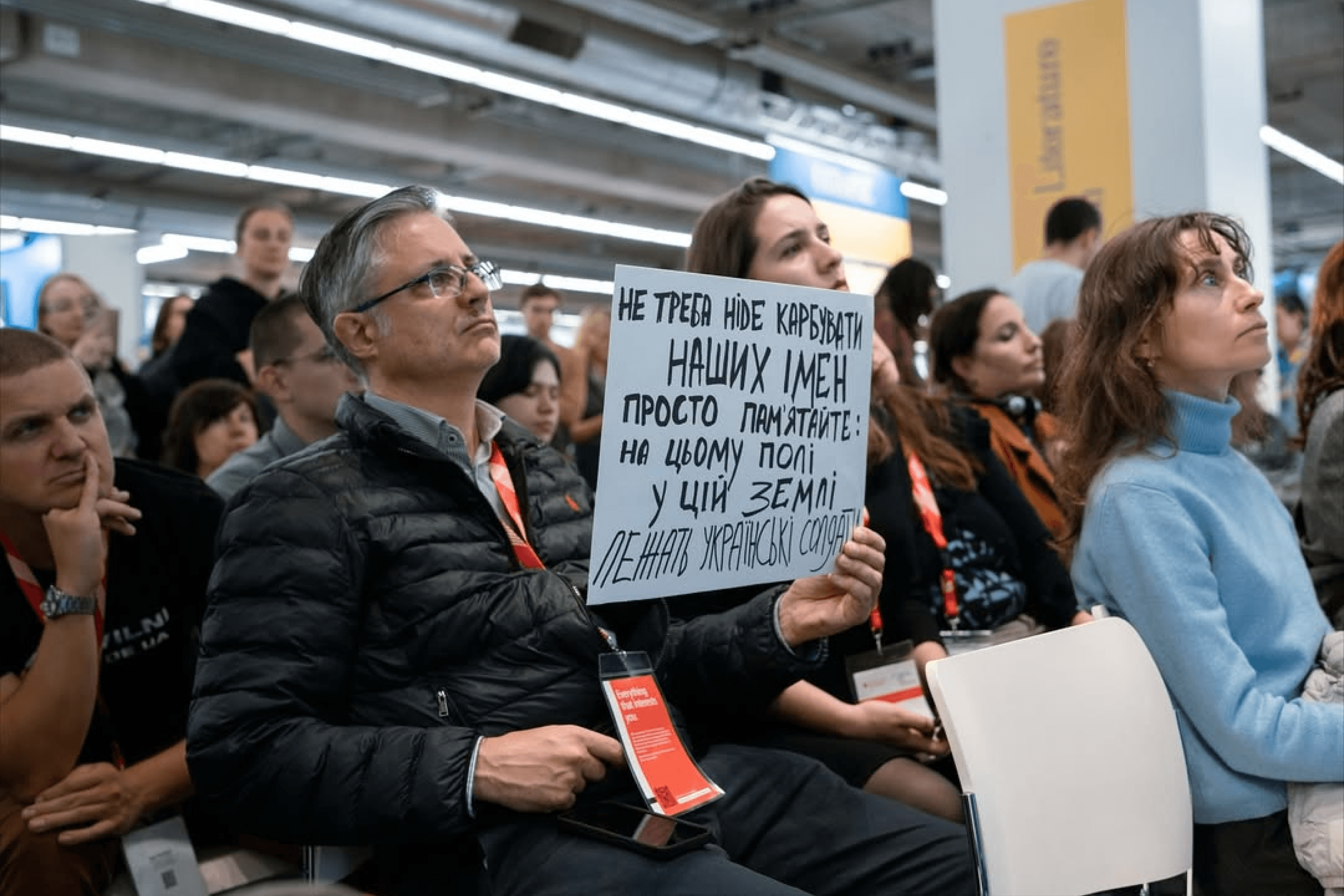

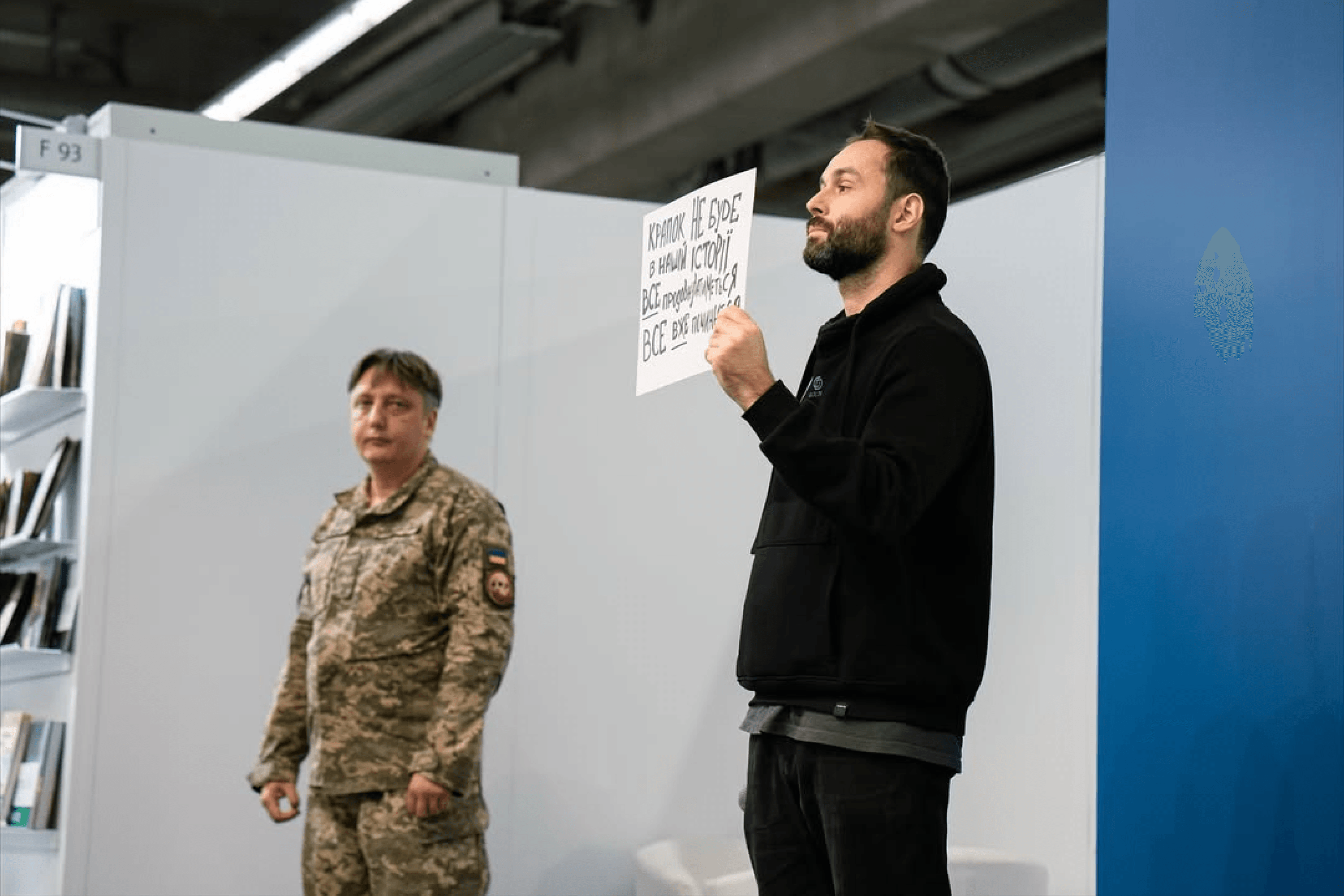

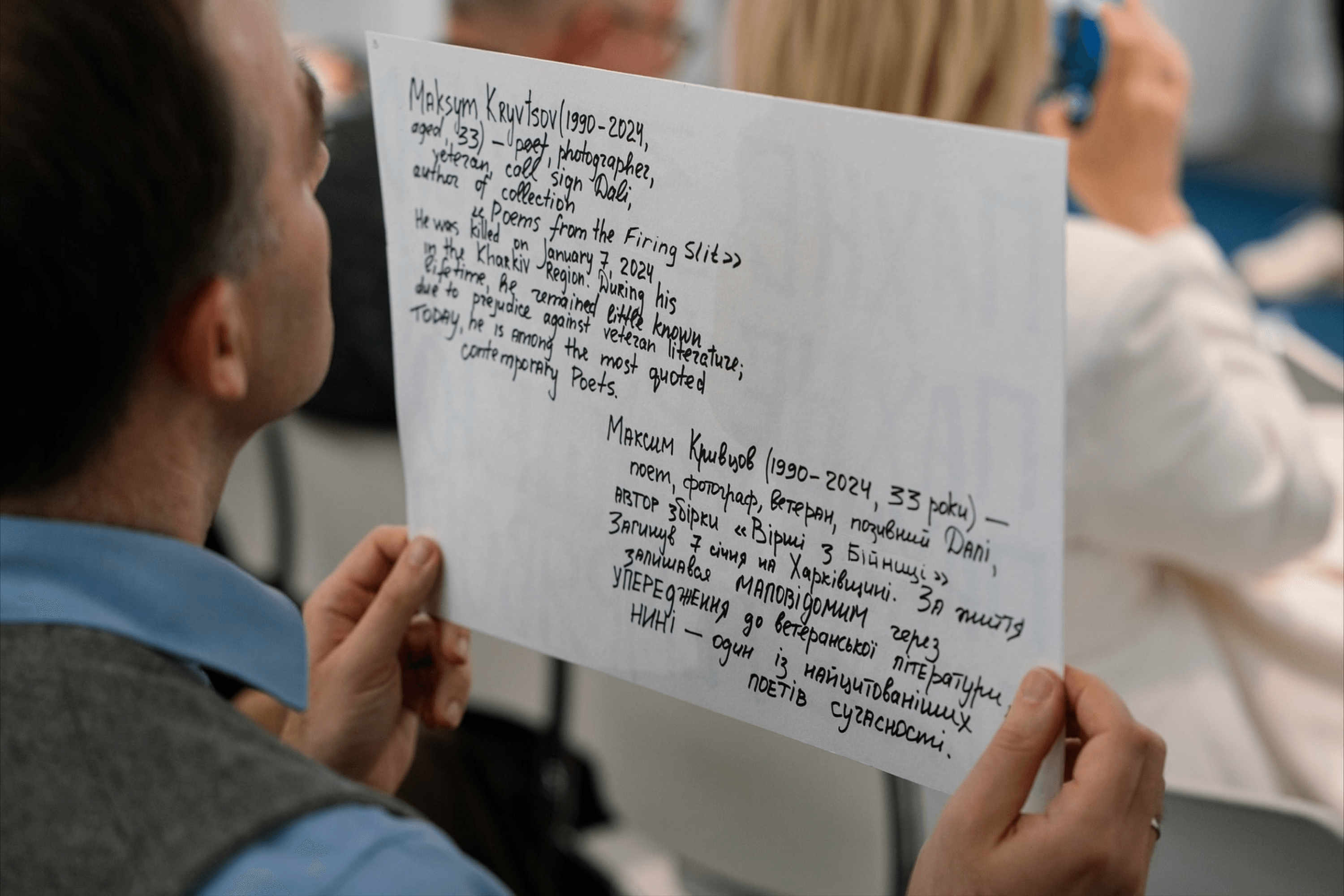

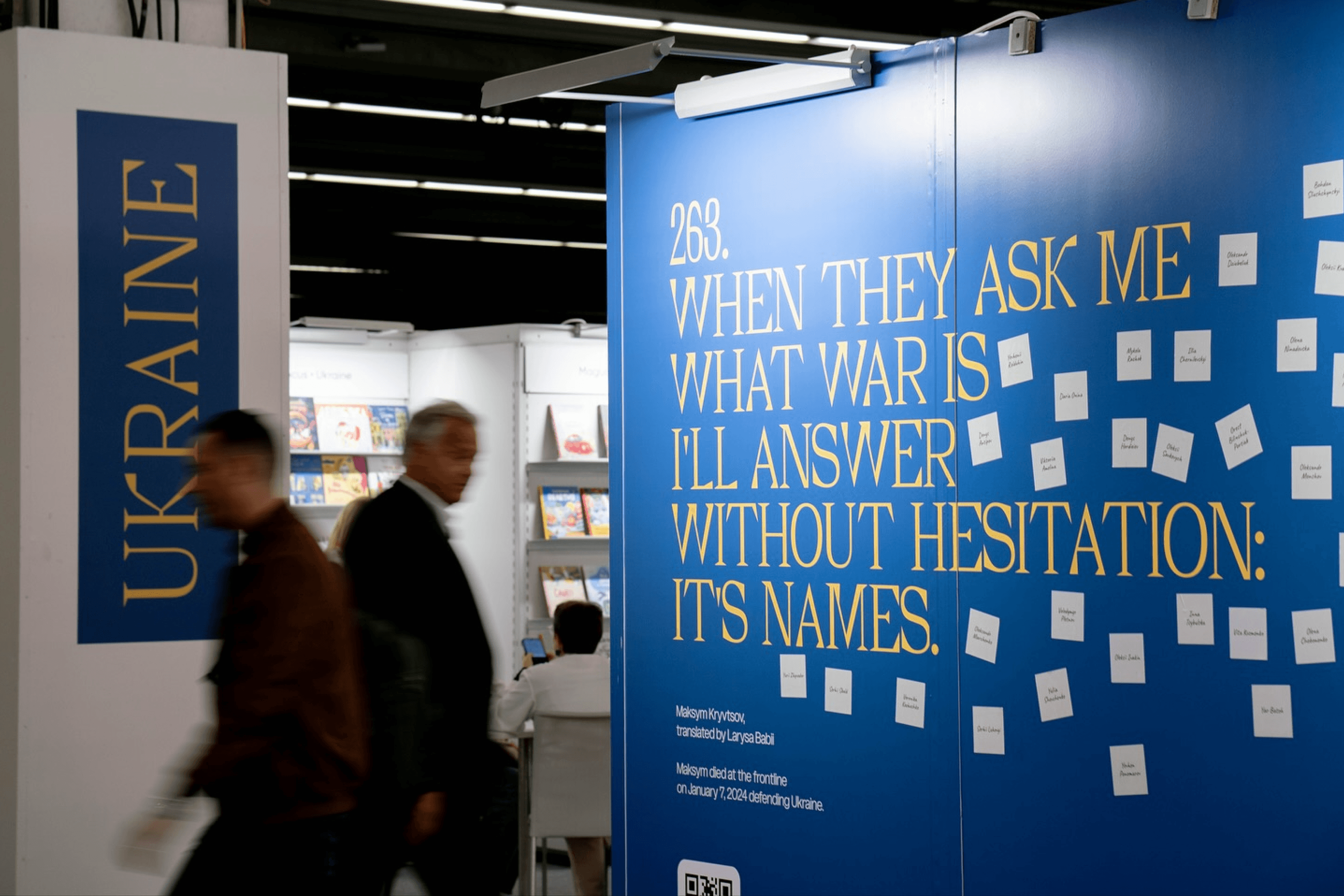

It’s worth promoting not only living authors but also those killed during the war. At the Frankfurt Book Fair, Cultural Forces and the Ukrainian Book Institute presented a project— “The Unwritten”. It collects information about male and female authors who died from Russian aggression. For a certain period, the thesis that foreigners were tired of the war in Ukraine, tired of hearing our stories about pain, trauma, and what Russia is doing to us, was super popular. But it turned out that foreigners are ready to listen actively: diplomats, writers, and publishers from other countries were very interested in this project at the stand in Frankfurt.

The market reacts to what is happening: whatever there is a demand for is quickly published. And it’s normal that there are texts of different levels. This is the reader’s demand: some need good analytics and reflection, others want the events to be as simple as possible, and some want to have a book with Zelenskyy on the cover on their shelf. The main thing is that we have an assortment, because if we don’t offer it, Russia will. I hope that there will definitely be no roll-back to the time when the Russian-language book was the major part of the Ukrainian market.

It’s important that writers-servicemen come to events abroad: Artem Chekh, Kateryna Zarembo, Artem Chapeye. In each country, talking about the war is necessary in different ways. And you cannot perform without knowing the loud news: what hit the foreign press will likely sound—like a scandal with Mindich or the Russian attack on the Factor-Druk printing house. And you need to understand what to say about it.

We show Ukraine not as an opposition to Russia, but as a self-sufficient state with a powerful culture. And when they try to talk to us about Dostoevsky, we say: “Let’s talk about Stus“. We need to explain abroad why it hurts us when they still want to seat us with Russians at the same table, and why they attacked us, and why we are against the imposition of Russian culture.

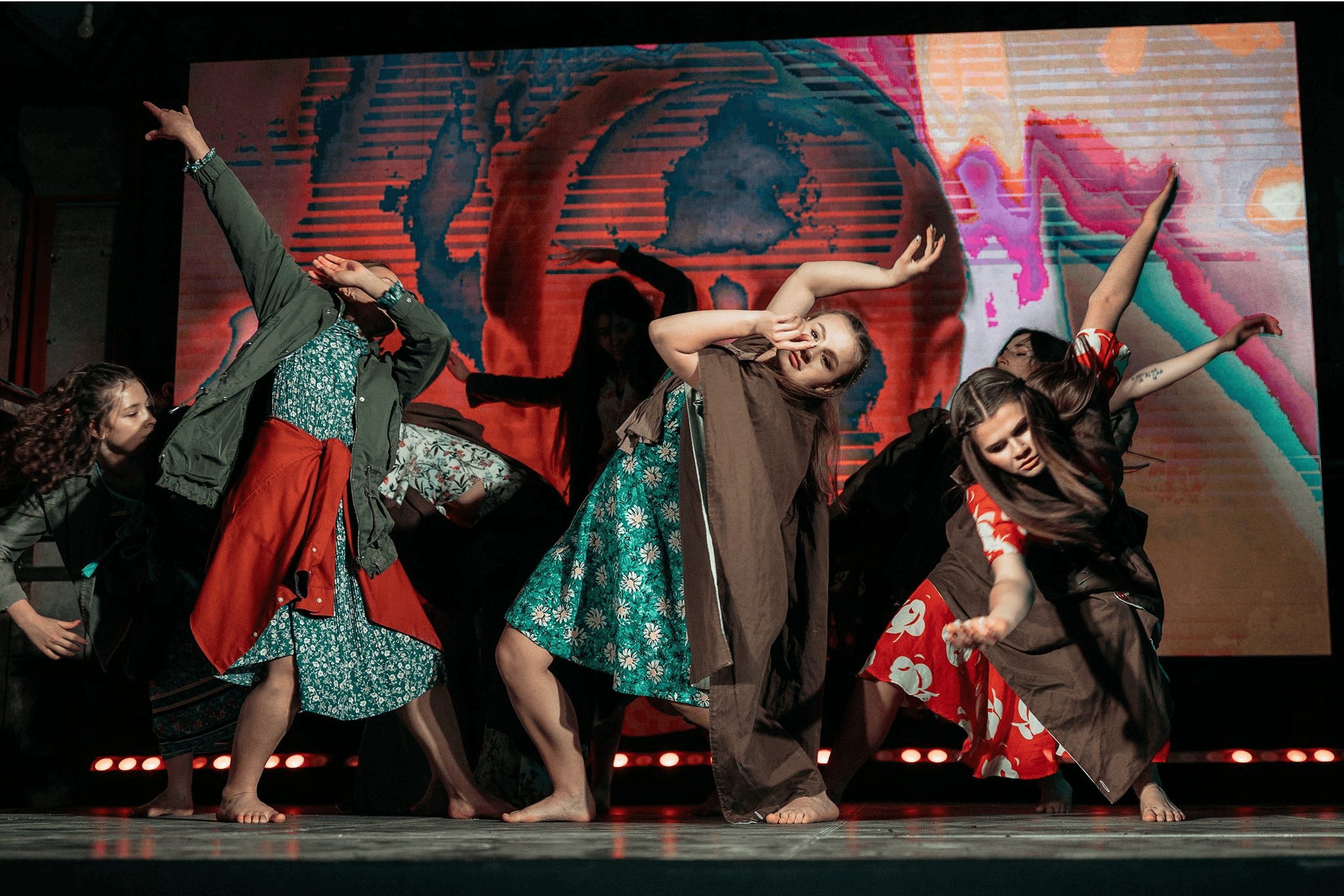

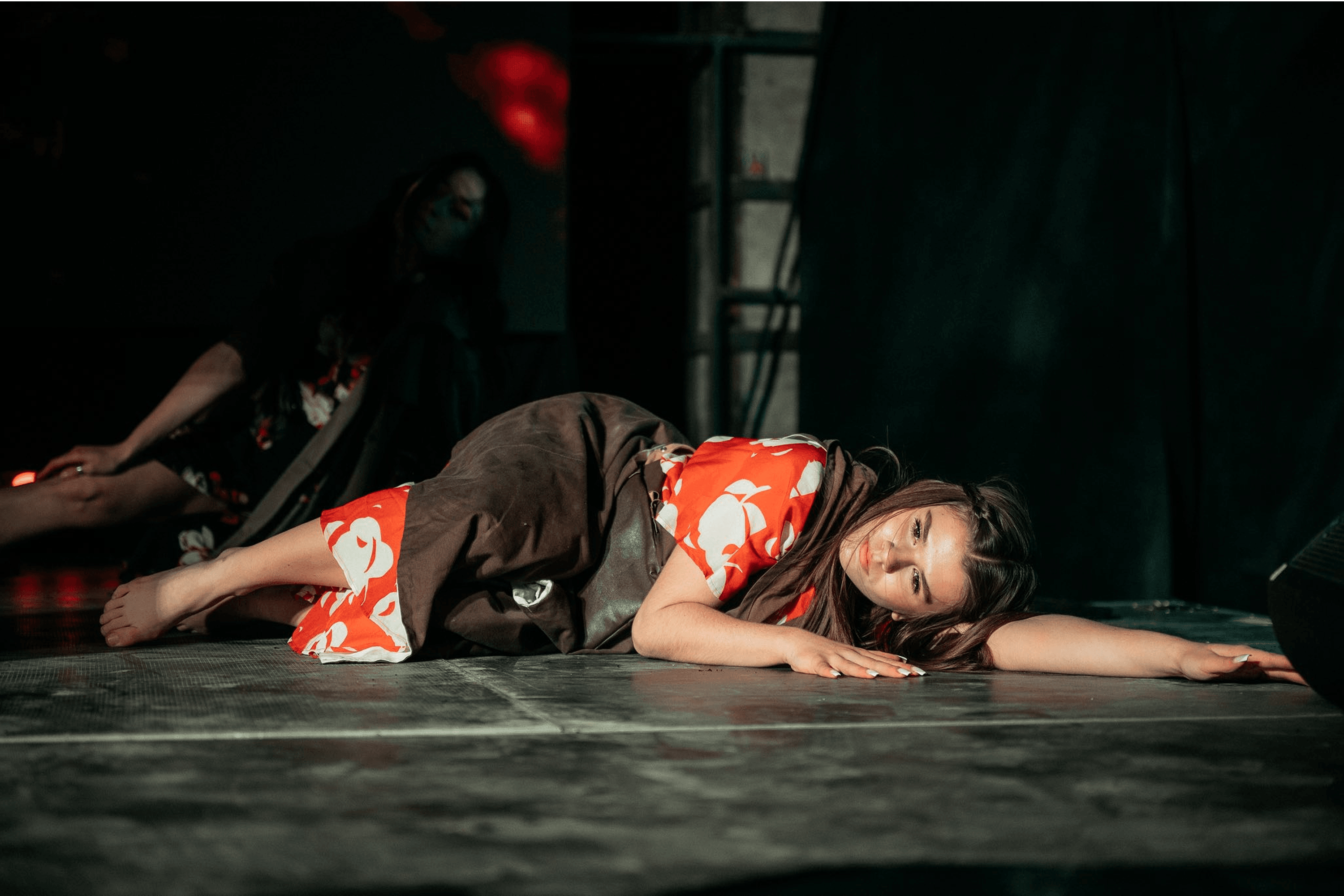

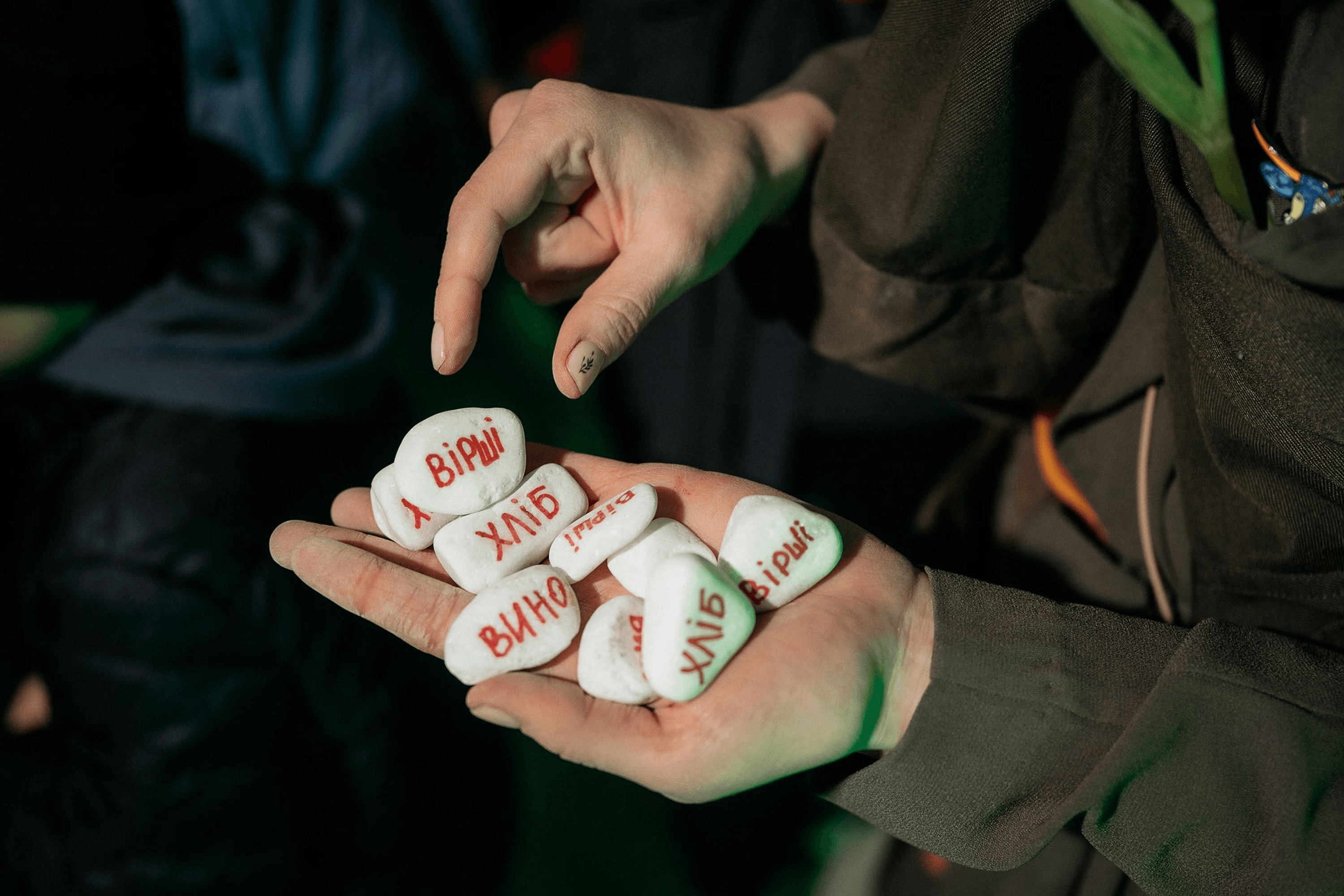

The Soviet Union distorted the perception of many cultural figures. De-bronzing the classics is important, taking them off their pedestals and looking at them as people. When we see in Stus not only a fighter but also learn what he lived by, whom he loved, and what he dreamed about. Because there are gaps not only in translations but also in the Ukrainian market: regarding periods of our history and biographies of artists and philanthropists. Does anyone know which woman was the founder of the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy? Or the incredible stories of the Symyrenkos or Khanenkos? The fact that literary projects are appearing, such as MUR, which simply tore up the Ukrainian market with their performance, is proof of how interested Ukrainians are in learning about their own.

I dream of walking into bookstores in European cities and seeing Ukrainian authors there. It shouldn’t be a separate shelf with Ukrainian texts, but ours among the American, English, and French ones, because that means the books are selling. For this, high-quality analytics are needed: to understand which text to go to which market with, so that it hits the mark the first time. And strong cooperation is needed between Ukrainian business, non-governmental organizations, and state institutions: to agree among themselves and do their work well. Not to put spokes in each other’s wheels, but to be a support for one another.