Gar O’Rourke was born into an Irish family in a small mountain village in the west of Ireland—Clifden. The family moved often: in his childhood and teenage years, Gar lived in New Zealand and various Irish towns. When he turned 18, he set off for London to study landscape architecture at Kingston University. After graduating, the young man decided to head out into the world to travel and find himself. Over several years, Gar worked a large variety of different jobs, including an outdoor sports instructor, lifeguard, bartender, waiter, and rickshaw cyclist. Until he eventually realized that his true passion was documentary cinema, and he wanted to create it himself.

O’Rourke shot his first film in Ukraine in 2019—it was the short film Kachalka about the outdoor gym in Kyiv’s Hydropark. Filming for his second, the 90-minute Sanatorium, took place during Russia`s full-scale invasion of Ukraine at the Odesa mud resort Kuyalnyk. The world premiere took place at the international documentary film festival CPH: DOX in Copenhagen in March 2025. The film was acquired by BBC Storyville, and the Irish Film and Television Academy submitted it for the 2026 Oscars, representing Ireland in the “Best International Feature Film” category. It has also been longlisted in the Best Documentary Film Category.

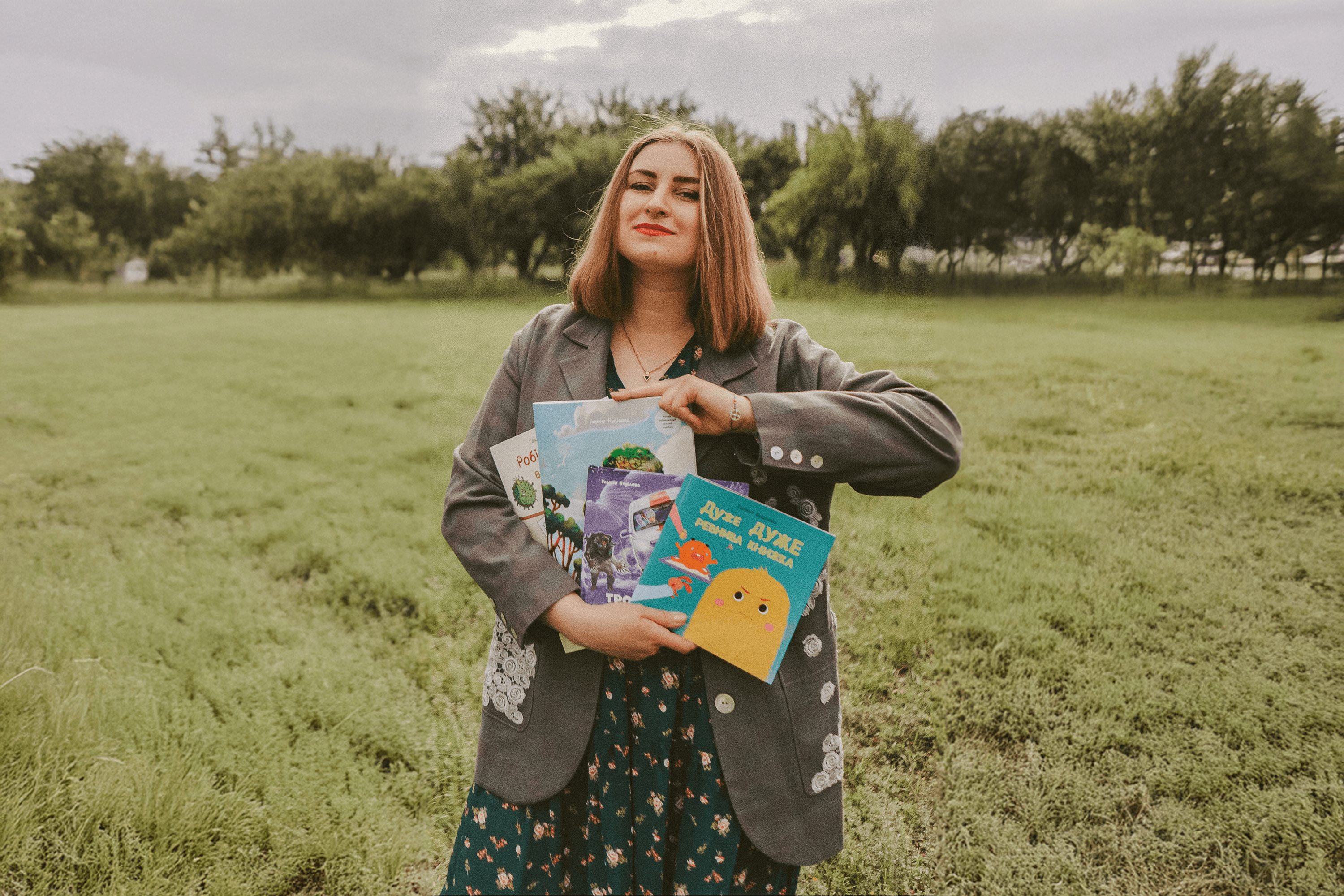

YBBP journalist Mila Shevchuk spoke with Gar O’Rourke about his search for a profession, filming in Ukraine before and after the full-scale invasion, the common traits of the Irish and Ukrainians, and the popularization of the Irish language.

How did you choose the career of a documentary director?

I did poorly in school, so the chances of getting into a university in Ireland were slim. I moved to London and enrolled at Kingston University, where they disregarded my previous academic results. I was always interested in filmmaking, but I couldn’t convince my parents that I should pursue it. So I trained as a landscape architect, but only worked in the profession for a very short time. Instead, I decided to head out into the world and figure out what I was good at. And over four years, I tried so many different jobs: I was an outdoor sports instructor, lifeguard, bartender, waiter, even a rickshaw cyclist.

One day I watched Tamir Moscovici’s short film Urban Outlaw, and it made such a powerful impression on me that I thought: I should be making documentaries, this is what interests me the most. So at 24, I moved to Canada. In all of the film industry, I had only one contact, and that person worked in Toronto. It was my only ticket there. Besides, opportunities in Canada were way more diverse than in Ireland. So I went to work in the film industry—in the lowest positions. I did literally everything they allowed me to: I was a producer’s assistant, second or third assistant camera, and videographer for commercial and corporate projects. To earn money for my own camera, I took on extra work, mainly shooting weddings. There I learned many skills that became useful for documentary filmmaking: shooting under time pressure, learning to anticipate the right moment, and achieving the maximum with minimal technical possibilities.

Then I founded my own video production company and made corporate videos, commercials, and music videos. Eventually, I returned to Ireland, worked in my video production for a while, and later was invited to collaborate with the well-known Irish film production company Venom Films. Once, a producer asked if I had an idea for my own documentary film. And I did: it was the concept for Kachalka, a short film about the outdoor gym in Kyiv’s Hydropark. That was seven years ago, and I have since directed three documentary films.

How did you find funding for your first film?

The Irish are lucky; our country values cultural production and directs a significant amount of money to support filmmakers. Former President Michael D. Higgins was the Minister for Culture in the 1990s, and he realized that Ireland would never be a hard power, as we are a small island without a powerful army. Instead, we have cultural export, and we must invest money to have influence in world culture. My first film received state funding for short documentary cinema—in particular, it helped that I had been in video production for about 4 years, and the production company Venom Films is very well known.

How do you choose themes, countries, and locations for your films?

You should choose what is interesting to you personally. Not what others expect, and not what is simply your comfort zone. You have to challenge yourself. I think I should choose more ideas in English, as I’ve made three films in foreign languages, which is hard. However, that is also part of my challenge.

The idea for Kachalka came about like this: my brother lived in Kyiv for six months and went to the gym in Hydropark. Once he sent me a video, and it looked absolutely wild: such a super-masculine, almost aggressive atmosphere. I thought there could be a bit of comedy there, and depth, not just giant guys. I liked the community there.

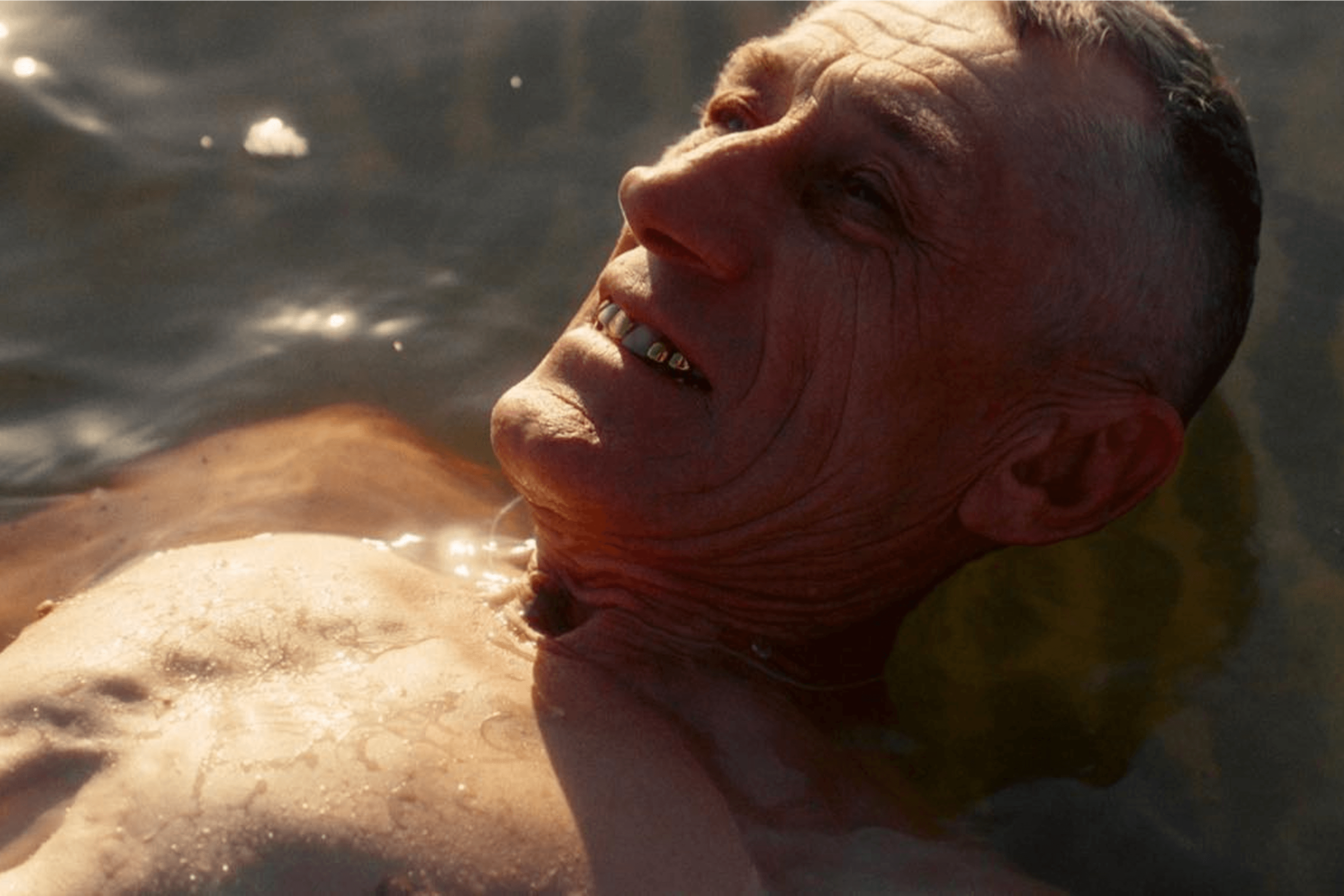

The idea for Sanatorium appeared during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown, when we couldn’t leave the house. Life paused, there was time to think about the past and future. And that’s when I discovered the wonderful world of sanatoriums: my Ukrainian friend told me about some of them. I started researching this topic and found the Kuialnyk sanatorium in Odesa, saw some fantastic photos of this place—and four weeks later I arrived in Ukraine. I visited this sanatorium, lived there for 10 days, and underwent all the procedures: hydromassage, electromassage, salt therapy. I even tried a mud bath; it’s quite pleasant.

Film ideas arise from what troubles me personally—often unconsciously. Kachalka was a way to explore machismo. I come from quite a macho family. I never particularly felt that way and wanted to see what was behind it. In Sanatorium, it was interesting how we heal, and how we use humor for this—even in the darkest times, as Ukrainians are doing now.

However, sometimes ideas come from nowhere. This year I received an email from an Englishman who wrote: “I saw your film on the BBC, and I have an idea that matches your sense of humor and interests.” I liked the idea, I contacted him, and we have already officially submitted applications for funding for this documentary film.

What was your first impression of Kyiv and Ukraine?

I first came to Ukraine in the winter of 2018 to prepare for shooting Kachalka. It was dark and freezing, I went straight to Hydropark and saw the scene—a giant man about 2 meters tall training shirtless, with steam coming off his back! It looked like madness and was very different from anything I had seen at home in Ireland—although I understand that even for Ukraine this is not a typical situation. And once I was persuaded to jump into the icy river absolutely naked. When I did it, the people who persuaded me jumped too—but for some reason not naked. I didn’t understand what was happening, but I quickly fell in love with Ukraine.

I made several friends there—they helped me better understand the country and culture, the local context. This is very important for a director.

In Ukraine, I was charmed by literally everything I saw: for example, I noticed that in cafes and supermarkets people do their jobs very well—in Ireland or Portugal, where I live now, you don’t often meet such care, focus, and level of service.

You filmed Sanatorium already during Russia`s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. How did you manage that?

We researched this topic almost a year before the full-scale invasion, I spent some time in the sanatorium, got to know the staff and guests. A few months before the invasion, the search for funding began: Venom Films was fundraising through various organizations in Ireland. We were also considering co-production with the BBC and had co-producers in Kyiv—2332films.

Then the Russia`s full-scale invasion began, the sanatorium closed, and we thought it was impossible to make the film now. Seven months later, everything changed: the sanatorium resumed work, I went there again—and saw a new story. Now it wasn’t just about healing, but about human resilience, when ordinary things become extraordinary, and life goes on despite everything. This was felt literally in everything: for example, when elderly ladies apply therapeutic mud to themselves, with smoke from the shelling of Odesa visible behind them. Despite the war, people just want to live.

Those who haven’t been to Ukraine during the war often think that there is only destruction and death there. And this is indeed part of the reality, but I wanted to show everyday moments close to everyone. For example, in Ireland there are no air raid sirens and explosions nearby, and many can recognize themselves in a character who came on vacation with his mother, who happens to be a bit overbearing. Ultimately, many different layers appeared in the film—ones that were not in the initial concept.

Finding funding was very difficult: because documentaries do not have a written script like feature films, we have to capture the whole story of the characters in the present tense, and doing this in a shelling zone is extremely hard. So it took several months to convince donors. Since I had already shot one film in Ukraine and had been there several times after Russia`s full-scale invasion, donors felt that I understood the situation, and we would be able to shoot it. In particular, thanks to our co-producers in Ukraine, because it is important to have experienced partners who help on the ground.

How long did it take to shoot and edit Kachalka and Sanatorium?

We shot Kachalka in 4 days, Sanatorium in 45. But before filming, there is always a long preparation period when we research the topic, write out what the story, the visuals, the sound should be like. I like to have a clear arc in my head—we start the story here and set off on a journey to a certain point. And only in editing do you find various connections you hadn’t even thought of before. Kachalka was edited in 2.5 weeks. Editing Sanatorium took 23 weeks, because we had to make two versions: one for film festivals, the second for broadcast on the BBC Storyville documentary program.

Usually, directors have their secrets of working with people. What are yours?

It helps that I am Irish: we are friendly, don’t have a complex ego, we are interested in others, we quickly establish connections.

Experience also helps: I worked a lot in restaurants and bars when I was 20, and there I learned to understand people, to make contact. In a documentarian’s work, the ability to establish contact is very important, as the final result depends on how comfortable the story’s characters feel in front of the camera.

That’s why I start building a connection with the characters long before filming begins: conversations via Zoom, informal communication. When I’m shooting, I try to be invisible. Sometimes I truly direct the scene, and other times I try to capture the moment so that everything is alive and natural. It’s difficult: I want everything to look its best, the cameraman and I think about composition and framing, but at the same time considering that every time you move the camera, you remind the characters of its presence.

Do you keep in touch with acquaintances from Ukraine?

Yes, I keep in touch with the people I worked with. I correspond with Serhii, the local producer and translator who helped immensely with the filming of Sanatorium and Kachalka. He often tells me Ukrainian news. I communicate with Denys Melnyk, who was the cinematographer on Sanatorium. I correspond with some of the characters, but they don’t speak English.

Are you familiar with Mstyslav Chernov, the Ukrainian director who is also contending for an Oscar in the same category for the film 2000 Meters to Andriivka and has already received one for 20 Days in Mariupol?

This year I traveled by train from Warsaw to Kyiv with him; we had a great time. Mstyslav is a pleasant person and an important director for Ukraine. Everyone who walked past us on the train recognized him and wanted to talk. We were together at the Docudays festival for a few days. I believe that he is a fantastic ambassador for Ukraine in the world.

You filmed in Ukraine before Russia`s full-scale invasion and after it began. Did you notice a difference in people?

Definitely. But a lot depends on the circumstances: you can be in Kyiv the day after a terrible shelling—and then it is felt more strongly. My general feeling: people are functioning on a daily basis quite well, but everybody is carrying trauma, and that has a psychological impact massively, I could see it in people's faces, it`s even because just not getting a good night sleep permanently. This summer, I was walking the streets of Kyiv with a friend, and an air raid siren started. My friend continued talking to me as if he didn’t even notice it. It’s hard to imagine that this would become the norm for me. But for Ukrainians it has—after all, they have been hearing the alarm every day for almost four years. It’s amazing that despite this they cope with everyday life, work, live a supposedly ordinary life. But everyone carries a trauma inside that has an effect. I see it on their faces.

I tried to show this in Sanatorium: when there was an air raid alert in Odesa and then explosions sounded in the distance, people were not scared, they didn’t run. It seems to me that Ukrainians were resilient even before the war started, and it only revealed how mentally strong they are.

I don’t know how people in other countries would react to these situations. I always think about it: if missiles and drones were flying at Ireland, how would the Irish react? I have no idea. But I don’t think we would be so calm. I admire the Ukrainians' ability to adapt.

You noted that Ukrainians and the Irish are united by a sense of humor. And what other common traits do you see?

Perhaps it’s the absence of empty words. Ukrainians are quite direct—just like some Irish people. And also our countries have similar experiences: Ireland was a colony of the British and also suffered violence. Similarly Ukraine, which was oppressed by different empires at different moments in history.

Previously, there were many emigrants from Ireland in the world. Has this process stopped? In the 1970s, there was an Irish government program aimed at returning emigrants home. They were offered free education or jobs. How is it now? And what were your reasons for moving to Lisbon? Why there specifically?

Ireland has historically been a poor country, so people constantly emigrated. A new large wave of emigration began during the global recession in 2007: people were again leaving Ireland for Australia, Canada, or America. Some of them later returned home, some didn’t.

It is difficult for young people in Ireland: salaries there are quite good, but life is expensive. There is a housing shortage, and rental prices are incredibly high. If one is young and lacks a stable job with a good salary, it’s almost impossible to rent a separate apartment. You have to live with other people, but even that is expensive. This is one of the reasons why people leave.

I lived in Dublin for 7 years, and then I felt it was time for a change. I hate this expression, but I wanted to “reinvent myself.” And I fell in love with Portugal: the culture, the climate, and a more balanced lifestyle. I moved here about a year ago. It’s a great place, there is a good filmmakers community here. And there is also a large, friendly Ukrainian community.

Maybe I will return to Ireland. On the one hand, a change of scenery and environment gives a push for inspiration, refreshes the view—and this is important for an artist. But at the same time, I feel guilty living here—because the Portuguese have the same problem as in Dublin. It is difficult for locals to rent housing, life here is often too expensive for them. This happened because Portugal welcomed foreign investors and for the last 10 years issued golden visas and permitted unregulated daily rental of housing to tourists without regulation.

Do you speak Irish? Did your parents speak Irish to you?

In Ireland, the national language is Irish, but everyone speaks English. I only speak a little Irish. But my mother speaks fluently: there are regions in Ireland where they speak exclusively Irish, she worked in one of them and used Irish every day.

In recent years, interest in the Irish language has intensified. One of the reasons is the band Kneecap. These are three hip-hop artists from Northern Ireland who speak only Irish and have become extremely popular in the world. They made a biographical film that won an award at Sundance. Their music is in Irish, and it inspires young Irish people to learn their language more.

Ireland submitted your Sanatorium for the Oscars—a film in a foreign language. Is this part of a multicultural filmmaking policy?

Ireland is small, we don’t produce many films. In the last three years, one film was nominated, and last year one film made the shortlist—this brings us back to the value of supporting culture, particularly filmmaking; it is really felt in Ireland. We are a nation of storytellers, it’s in our blood to tell stories. In an Irish pub, you will very rarely hear people discussing ideas; usually, they tell stories.

I consider Sanatorium a Ukrainian film. Ukrainians love it the most—they feel something special, their own, in it. So it’s amazing that Ireland chooses such projects to represent the country at the Oscars. Perhaps the Irish are unique in this sense: we are interested in other countries and their cultures because culturally we look outward.

What would an Oscar nomination mean to you?

I’m not looking for public recognition, although it is sometimes pleasant. I am interested in whether an Oscar nomination can help me get more interesting projects made. Fame and success are something temporary and unstable. It is more important to consistently implement ideas you believe in. And in this, the success of the film can help the entire team that worked on it. As they say in English: “A rising tide lifts all boats.”

For the ego, it would be great to win an Oscar someday, but I am sure that if it happens, there is a chance that I could wake up depressed the next day. I’ve heard many stories of people who said: “I won an Oscar, but two weeks later I hated myself.” It’s a good goal, but awards are a by-product of activity, not the reason why I do something.

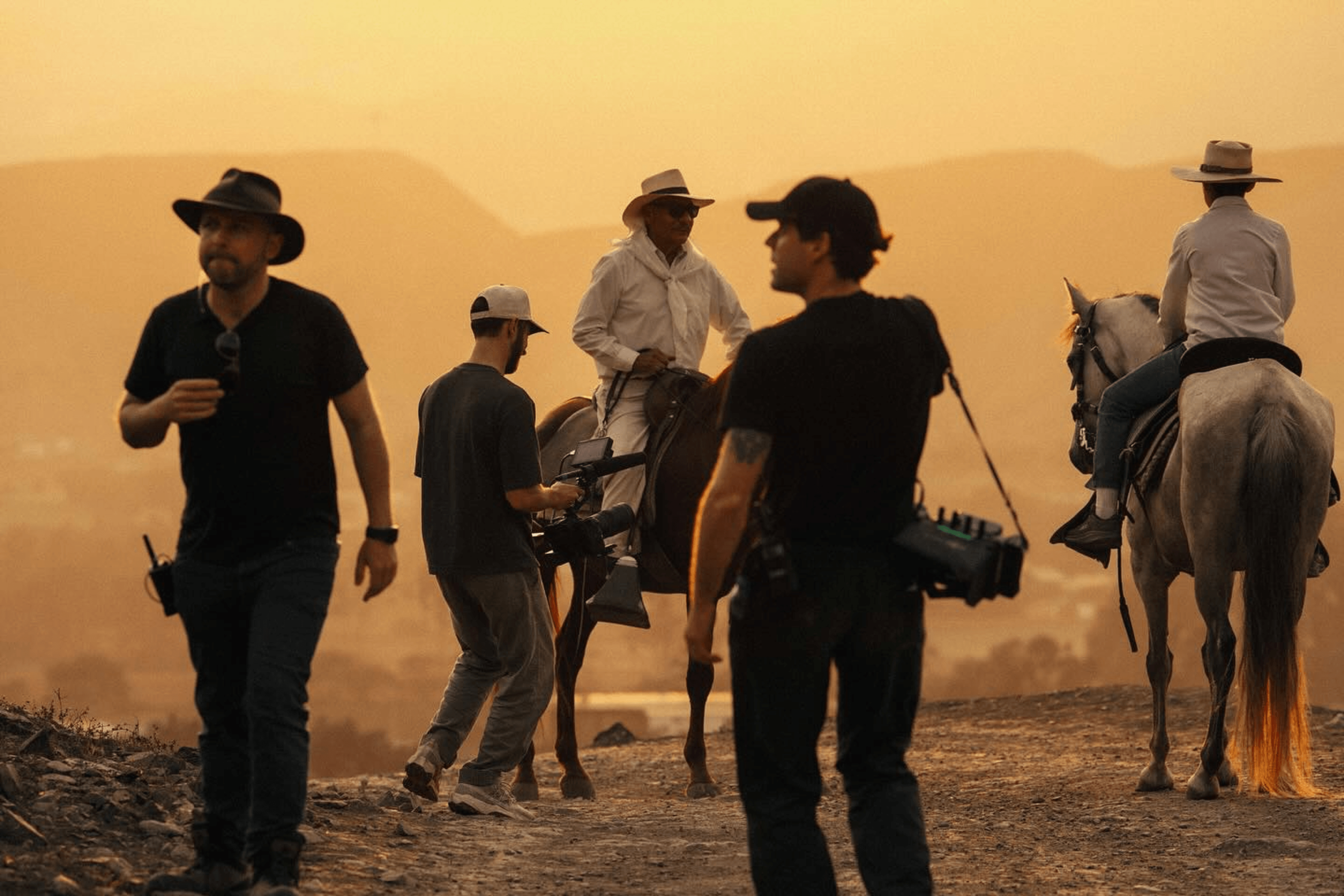

You shot your last film in Italy. What is it about, and when will we be able to see it?

It is called The Siege of Paradise, the action takes place in Cinque Terre, an extremely popular tourist spot on the coast. It’s a kind of tragicomedy: the film reflects the opportunities and challenges of tourism. After all, overtourism has become a problem in many places in Europe: there are more and more representatives of the middle class in the world who have the opportunities to travel and want to visit everywhere.

Artificial intelligence and related technologies are developing actively now. How do you think this will affect filmmaking? Are you worried that AI might take your job?

I think AI will inevitably enter all industries. And art too—this year at the Tribeca Film Festival in New York, a short film completely created by artificial intelligence was shown. It’s very exciting that AI makes it possible to visualize anything, even with a small budget. However, I would not want to watch such films. For me, for art to be real and valuable, there must be some complexity in the process: it involves a struggle inside us, and AI eliminates this struggle. So I don’t feel resonance with things created so easily.

I am most interested in documentary cinema, and this is always something real, human, authentic. So, perhaps, documentary filmmaking is one of the safest categories in the film industry in this sense.

If art must be with a struggle, then what struggle is in your work?

There are many difficulties: it is hard to get funds for filming, it takes a long time to submit applications for funding, and then to film festivals, something can go wrong on set, someone in the team gets sick, terrible weather happens. And for me as a director, it is sometimes difficult to avoid biases—false notions about some phenomena: an artist must question everything, because the beauty of creating the new lies precisely in exploration.

Do you dream of making a film on a specific topic?

I get a little obsessed with ideas for a while, implement them, and then get carried away by new ones. I have dreams, many different dreams. But I don’t have a single subject that I dream of filming. I am already very lucky to do what I love, so I try not to be too greedy in my ambitions.

You sound like a happy person, completely satisfied with life.

Regarding work and career—yes, 100%. When I’m making a film, it becomes my whole life, but outside of filming I try to know how to enjoy myself and avoid burnout. The career I chose really suits my personality: I am curious, I like to listen to others, I am interested in people. In the process of creating a film, everything that interests me comes together: storytelling, immersion in different cultures, music, photography. And when the film is ready, the result can have a positive impact on people: even if it’s just that someone feels great for 10 minutes after watching a movie or it makes them think about important things.