Kateryna Prykhodko has loved animals since childhood. Growing up on Sakhalin Island, she was surrounded by wild nature and the lifestyle of a small family farm. That childhood fascination turned into a profession: she trained as a veterinarian and worked in Kyiv, but later realized she longed for her own home and land.

She bought a house in a village in the Zhytomyr region, where she raised goats and began crafting cheese. What started as a small production for family and close friends blossomed into the StreKoza farm. With the onset of the full-scale war, Kateryna moved to Italy, where she now works alongside artisanal cheesemaker Eros Scarafoni. This is her story.

1

Kateryna Prykhodko was born on December 22, 1977, in Kyiv. Her father, a law student at the time, worked in the Soviet police, while her mother studied engineering at Kyiv Polytechnic and later became a university lecturer. Kateryna came from a family of professors, doctors, and civil servants. Her grandfather and uncle worked in the Council of Ministers, and her grandmother was employed at the Central Bank. But despite the impressive positions in the family, Kateryna does not consider her childhood to have been particularly lavish — though, as the only girl among a gang of cousins and nephews, she was certainly cherished.

In 1986, spurred by adventure novels, Kateryna’s father moved the family to the remote island of Sakhalin. There, her younger brother was born, and her dad took a job in criminal investigations. Work on the island came with high pay and the promise of a generous pension. Kateryna became fascinated with Japanese culture during this time and started practising aikido and taekwondo. Her childhood, spent among misty forests and volcanic coastlines, taught her endurance, and above all, a deep appreciation for wild, untouched nature.

Life on the remote peninsula was full of activity. Kateryna’s family started a small farmstead growing their vegetables and raising goats and chickens. For Katya, this was her first experience caring for animals, a formative experience that influenced her future career path. Back then, she began training dogs, and at the age of 12, she assisted her mother in delivering baby goats for the first time.

“I’ve always had a deep love for living beings — the warmth of fur, the quiet rhythm of breath, the soft touch of paws, and that unspoken bond between us and them,” Kateryna says. “James Herriot’s All Creatures Great and Small was the book that lit the way for me.”

At 16, Katya returned to Kyiv and lived with her grandmother. She finished high school in the capital and was preparing to apply to Kyiv Polytechnic, just like her mother. But her heart led her elsewhere — she followed her passion and enrolled in the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine at the National University of Life and Environmental Sciences of Ukraine.

Kateryna’s university years fell in the early 2000s — a time when Kyiv was still a calm and very green city. She loved being outdoors and spent countless hours in the Holosiivskyi parks and woods, training dogs and prepping them for competitions. Her first Airedale Terrier, a gift from her grandmother, became her loyal friend and closest companion.

She married at 22 and had a daughter, but the relationship didn’t last. Just two years later, she found love again. Her second marriage, to Volodymyr, who is 12 years her senior, stood the test of time — they’re still together today. Kateryna completed her degree with a thesis on feline skin diseases and began working at “Zoodom,” a large pet supply store founded by the Italian company Ferplast. There, she worked as a veterinary consultant while also maintaining her private veterinary practice.

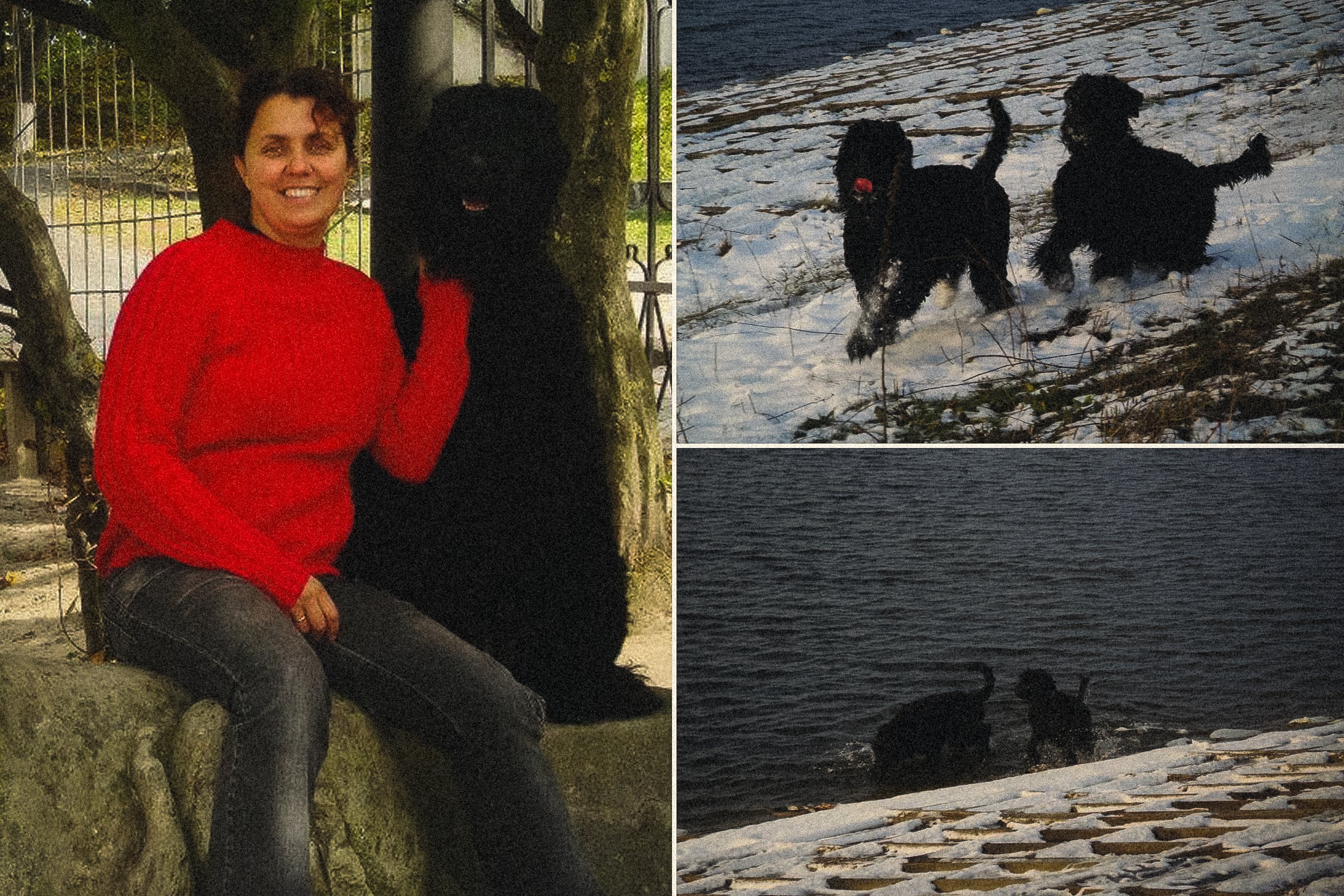

City life started to wear Kateryna down. She longed for space and the comfort of her own home. Her husband also had a unique passion — oceanic fish. They shared their two-bedroom apartment with two Black Russian Terriers, three cats, snakes, spiders, iguanas, and two massive aquariums holding 300 and 500 litres of tropical fish. In 2008, Katya sold the Kyiv apartment she’d inherited from her grandmother, and she and her husband bought a home in the village of Brusyliv. They started a little farmstead, and she decided to focus solely on her private veterinary practice — over the years, she had built up a loyal and growing list of clients. On average, she was making up to $2,000 a month dealing with complex and infectious animal diseases, an area with few real experts in Kyiv at the time.

The shift in lifestyle — new home, new rhythm, newfound independence — marked a turning point. She was finally her own boss, able to set her schedule. But country life came with its challenges: a large property to maintain, animals to care for, and a never-ending list of chores that demanded energy, patience, and adjustment.

2

Starting in 2009, a new chapter began at the family homestead — farming. Katya brought in goats, pigs, rabbits, and quail, and began experimenting with goat’s milk cheeses. Her first creations were bryndza and Adyghe cheese, and she threw herself into learning, researching recipes and starter cultures, and seeking advice from experienced cheesemakers. Word spread quickly, and her products gained popularity among friends and neighbors, and soon she realized it was time to scale up and sell her cheese beyond her inner circle.

The couple took their time to have more children. Her husband already had two children from his previous relationships, and Katya had a daughter from her first marriage, whom her second husband lovingly raised from a young age as his own. Kateryna decided to have another child at age 34, after experiencing the loss of several close relatives. In 2011, she gave birth to their son, Kyrylo.

Kateryna deliberately chose not to go industrial. For her, quality and hygiene standards came first. She kept the farm meticulously clean, implementing modern solutions like automatic feeders, self-watering systems, and odour-resistant animal bedding. Everything she sold was carefully portioned, sealed, and packaged with care. She firmly avoided the use of antibiotics and pesticides. Nearly all of it she handled on her own. Her husband kept his job in Kyiv, and the only help she hired was to clean the barns and stalls.

In the beginning, her farm products generated a steady but modest income. Katya says that in 2011, farming brought in around €500 a month in clear profit. For that time in Kyiv, it was a solid income — especially considering she didn’t need to buy groceries: milk, cheese, butter, sour cream, vegetables, fruit, and meat — it all came from her land. And on top of that, she continued her work as a veterinarian.

3

By 2015, Kateryna became seriously interested in professional cheesemaking. While most cheesemakers rely on instinct and tradition, Katya had a strong scientific background and realized she could go further in this craft. She named her farm StreKoza, a playful twist on the word for “dragonfly.” In Japanese culture, dragonflies are a symbol of freedom and the samurai spirit — qualities that, to Kateryna, reflected inner strength and independence.

“I was searching for a new way to bring together my love for nature and science,” she says. “So I tried making my first cheese — and it was like stepping into another universe. A world where milk is alive, breathing and transforming. From then on, I couldn’t stop — I devoured books, ran experiments, and kept learning everything I could.”

In 2017, Kateryna started selling baby goats, and with that, her income took a noticeable leap. Always forward-thinking, she built a detailed database for all the animals on the farm, including their pedigrees and productivity, based on principles similar to European dog breeding systems. At the time, the idea of developing goat breeding through exhibitions in Ukraine was completely new.

That same year, Katya started working with Kyiv restaurants Kanapa and Ostannya Barykada, and began showcasing her cheeses at food festivals to build awareness of her products. She kept rare breeds for Ukraine — Anglo-Nubian goats and Jersey cows — specifically to craft premium cheeses with white and blue molds. She also attended a restaurant masterclass by a German cheesemaker in Kyiv. He made a striking observation: “You have excellent cheese. Why borrow foreign names? Give them your own. This is a great product — but it’s not Gouda, and it’s not Cheddar.”

“I started making cheese with the soul of Polissia — the land I call home,” Kateryna says. “I wanted it to carry the mystery of the forests, the scent of wild meadows, the mood of the wind drifting from the swamps. For me, it wasn’t just food — it was an expression of my identity, a fusion of craft, land, and inner vision.”

Over time, Prykhodko created about 15 varieties of blue cheese — some of them seasonal, made only in spring or summer. She also crafted six types of bloomy rind cheeses, three styles of cream cheese, and a fresh lactic cheese similar to cottage cheese. Hard cheeses were rare in her lineup — made in small batches just for the family, since producing them for sale would have required a proper aging facility.

By 2019, Kateryna’s farm had reached new heights. The herd grew to 40 goats, she added three cows, broiler chickens and pigs. This expansion allowed Kateryna to establish strong relationships with regular customers — some families received her cheese and dairy goods every month. The farm was now generating a steady profit of over $1,000 a month.

That same year, Katya discovered the Slow Food movement — a global response to the rise of fast food. For her, it wasn’t a business model or passing trend, but a deeply rooted philosophy based on respect for the land, people, time, and taste. Slow Food is guided by three core principles: good, clean, and fair. “Good” means food should be delicious, authentic, and made with skill. “Clean” means natural ingredients and living milk — nothing artificial. And “fair” means standing up for small producers, ensuring fair prices, and keeping traditional practices transparent and accessible.

Katya became an active participant in major cheese festivals. At Cheese World Ukraine, she took home the top prize — a trip to Bra, Italy, where she was introduced to Italy’s rich cheesemaking traditions.

“I was the first Ukrainian cheesemaker ever to represent the country at the legendary Bra Cheese festival — held every two years by Slow Food Italy,” Kateryna says. “It wasn’t just me presenting my cheese — it was recognition that Ukrainian cheese belongs on the world’s culinary map. I brought my signature cheeses and felt so much support and genuine interest.”

Shortly after returning home, Katya discovered she was expecting her third child. The news came with doubts and worries, but she decided to go through with the pregnancy. She was 40, and her husband Volodymyr was 52. There were big age gaps between the kids: 12 years between her eldest daughter and son, and 9 years between her son and the baby on the way. Still, despite all the challenges, Katya welcomed her daughter, Margaryta, in 2020.

4

The pandemic years were tough for the business. With markets closed and logistics disrupted, Kateryna worked directly with families, personally delivering her products to them. Holidays or expansion were out of the question, but she was still able to keep the family and animals well provided for. By 2021, things started to look up. Katya was planning to launch a large-scale cheesemaking facility on her property in the summer of 2022. She’d already purchased the equipment — all that remained was to finish the renovations.

As the threat of war loomed, Kateryna quietly began to prepare. Just two weeks before Russia’s full-scale invasion, she had arranged with a fellow farmer who agreed to evacuate her animals if it came to that. She stocked up on feed and fuel — just in case. “My husband tapped his temple and asked if we were getting ready for a siege,” she recalls. “But a good stash never hurts the pocket.”

On the morning of February 24, Kateryna’s husband woke her with the words, “The war has started.” Almost immediately, her brother — who had emigrated to the U.S. years earlier — called and urged her to remove the geolocation data for StreKoza. “The Russians won’t care if it’s a big farm or a small one,” he said. “If they start bombing, they won’t stop to check.” The thought hit Katya hard: if they came toward Brusyliv, what would happen to her and her family?

A week later, he called again — this time, he was crying. “Please,” he said, his voice breaking, “you need to leave. They’re coming your way. You have a few days at most — don’t wait.” Hearing her steady, self-assured brother reduced to tears shook her to the core. Kateryna and her family quickly began evacuating their animals. Within a day, they’d moved them all to a farm 30 kilometres away. The same farmer took in most of her cheesemaking equipment for safekeeping. The Russians stopped just 15 km short of Brusyliv. Katya’s farm survived, but she never returned to the village. Some of the animals remained with the farmer, and others were taken in by friends.

Kateryna and her family first went to stay with friends in Rivne, and by April 2022, Kateryna made a difficult decision: she packed up her family and fled the country. “At that time, I had four dogs — two large Black Russian Terriers, an elderly Chihuahua, a French Bulldog, a 13-year-old cat, three children, and my mother,” she recalls. Her husband stayed behind and remains in Ukraine to this day.

Katya reached out to Yuliya Pitenko, head of the Slow Food Ukraine movement. Through Yuliya’s network and a Facebook post, an Italian cheesemaker named Eros Scarafoni offered help. He invited Kateryna and her family to his farm, Fontegranna, in the small Italian town of Belmonte Piceno.

“We drove for three days,” Kateryna recalls. “Two thousand kilometres in my car with the animals and my toddler. We travelled 500–600 kilometres a day, stopping for breaks when we could. I had just the bare minimum in my suitcase: a few clothes, an embroidered vyshyvanka, and a cheesemaking book I never got the chance to read.”

5

Kateryna’s meeting with Eros Scarafoni felt almost mystical. Back in 2019, during her first trip to Bra, she’d picked up a few Italian books on cheesemaking published by Slow Food. She didn’t speak Italian, only a few basic phrases, but planned to read them with a translator. One of the books described a technique for aging cheese in walnut leaves, a method used by only one cheesemaker. Katya took inspiration from the idea and adapted it to create her own signature cheese.

Later, when she moved to Italy, she brought her cheesemaking library with her, and that book was there too. One evening, flipping through its pages, she suddenly realized why Eros Scarafoni’s name had sounded so familiar. He was the cheesemaker who used walnut leaves in the affinage process.

Later, Kateryna showed Eros photos of the cheese she had created, inspired by that very book. “I knew about you long before I ever came here,” she said with a smile. “It’s like the stars aligned for me to be here.”

Today, Kateryna works at Eros’s creamery and rents a small house nearby. He has years of experience, a lively farm where there’s always something going on, and a big family — his wife Irma, two children, and a grandson. For Kateryna, this partnership has meant more than just learning from a master. It’s become a source of comfort and support in a foreign country.

When Kateryna arrived in Italy, she thought she’d stay no longer than six months. The plan was simple: collaborate with Eros on a Ukrainian-Italian cheese and present it at the Bra Cheese festival, with no intention of working in partnership long-term. But life had other plans. Now, Katya works at Eros’s farm-creamery as a hired specialist. She earns €10 per hour, with her monthly income depending on the hours she works. Eros still leads the cheesemaking himself, Kateryna handles affinage, the aging process, along with caring for all the cheeses on the farm, managing the microclimate, shaping the right flavour and rind, and often making the cheesemaking itself.

Kateryna jokes that cheese brought them together. She describes their partnership like this: “It happened very naturally — not a business deal, but a genuine human connection. He’s the logical one, the one with experience. I bring intuition, sensitivity, and passion. He builds the structure. I create the emotion.”

Italy taught Kateryna to slow down. Literally — to breathe, observe, and let things unfold in their own time.

“The hardest part,” she says, “was feeling that I had the right to be here — a Ukrainian woman making cheese. Not Italian cheese, not a copy — but my own. And to find people who saw value in that and support that. Once I allowed myself to be who I am — that’s when real life began.”

Katya says she’s not trying to make Ukrainian cheese into Italian cheese. “My goal is to create cheese that speaks the language of my experience, memory, and homeland.” These cheeses are born at the crossroads of cultures — but with a Ukrainian soul. They don’t compete — they tell stories.

These days, Katya and Eros craft a full spectrum of cheeses that change with the seasons: Marava, Witch, Fern Flower (Fiore di felce), Snowy Grape, Makosh, and Broken Heart. Each of these cheeses has its own story, aroma, and character. And each carries a taste of Ukraine — even though it’s made with Italian milk, on Italian soil. The main challenge, however, is that Italians love their own. But if you’re not imitating but something new, “I wouldn’t say people line up for our cheese,” Katya says, “but every time someone tastes it, they ask, ‘Where is that flavour from? ’ That’s when I know they’ve discovered something new. We adapt the texture, adjust the method — but the heart of it remains unchanged: we’re making cheese born from two cultures.”

Katya works with raw, living milk — unpasteurized and ever-changing with the seasons. The same batch can behave entirely differently under the same conditions. But instead of seeing unpredictability as a problem, she sees possibility. Mistakes, to her, are potential new discoveries. Through food festivals and culinary fairs, Kateryna and Eros have begun attracting orders from gourmet shops, restaurants, and chefs who are on the hunt for something authentic. Their cheeses now appear in small, independent shops that truly appreciate uniqueness.

Katya says the war has sharpened her sense of mission. She is no longer just a cheesemaker — she’s a cultural ambassador. “Italians, French, Spaniards — they ask, ‘What do you eat at home? What does childhood taste like? ’ And we answer with cheese. The war made our voice stronger. It taught us how to speak about difficult things simply.”

Kateryna started learning Italian from scratch with a private tutor. Today, she uses it comfortably in both work and everyday life, though she admits she still hasn’t yet reached the level she wants. Her eldest daughter, Liza, has returned to Ukraine, while her son Kyrylo and youngest, Margaryta, attend local school and speak fluent Italian. Katya dreams of giving all her children access to good-quality European education. For now, she doesn’t have a clear plan about returning to Ukraine. For now, many of her current ideas and projects are tied to Italy, the projects she’s eager to bring to life right where she is.

6

In October 2023, Eros and Kateryna launched a free training course on the art of cheesemaking for Ukrainian farmers, to offer moral and professional support. Thirty people joined the course.

That same year, on November 9, Kateryna Prykhodko founded the online cheesemaking school StreKoza SCHOOL. “I wanted to create a space where it is safe to make mistakes, to explore, to find your own style” she says. “Our school is a place where cheese is born from the heart and not from strict instructions.” The school started with a private premium Telegram channel and a symbolic enrolment fee of €150. They purposely avoided sponsorships to protect their independence. The real value lies in the content that Kateryna shares. Eros enthusiastically supports Kateryna’s initiative: he answers students’ questions, films videos, and shares his cheesemaking secrets.

Now that the project has grown, Katya says they’re open to collaboration — but only with people who genuinely share their values. Her online students live in different regions of Ukraine, including temporarily occupied cities, as well as in exile across other European countries. Lessons take place even at night, since the school is not bound to any fixed schedule. The full-year cheesemaking course costs ₴1,500 per month, while one-month specialized courses are available for ₴500 per person.

Kateryna believes that Ukrainians are very talented but often lack confidence. Italians, on the other hand, are confident, but sometimes constrained by tradition. She sees herself building a bridge between these two extremes. Her students don’t just learn to make cheese, they’re learning to become creators: people who feel, think, and search. Katya plans to take StreKoza SCHOOL online cheesemaking school to the international level, and use cheese as a way to connect people across borders.

“Every student who joins our school ends up changing it just a little,” says Kateryna. “They bring their own family traditions, unique flavours of their region, own rituals, skills, and stories. And that’s when a real exchange happens — not just of knowledge, but of ideas. We experiment with herbal infusions, fermented herbs, aging in clay vessels, and the use of smoked wood. Each recipe holds more than just a method — it carries the spirit of the land we come from.”