If you turn off the Vistula River promenade near Krakow’s Grunwald Bridge, you’ll find yourself on Józefa Dietla Street, named after a prominent physician and former mayor. This tram artery runs alongside Kazimierz, one of Krakow’s most famous historic districts. Once a Jewish quarter, Kazimierz is now one of the city’s most popular tourist destinations. Just two blocks down, where Dietla meets Eliza Orzeszkowa Street, named after the Polish writer and translator, you’ll find restaurant Ciepło.

This cozy restaurant serves Ukrainian home-style dishes and is widely considered one of the most popular Ukrainian spots in Krakow. But there are no Ukrainian flags, embroidered signage, or folk-style clichés. Instead, you step into a modern, stylish space with a thoughtfully designed interior. It’s only the themed art exhibition on the walls, and the fact that the entire staff speaks Ukrainian alongside Polish and English that quietly reveal this to be a Ukrainian establishment. The restaurant was run by its 32-year-old co-founder Olena Mykhailovska.

In this interview with YBBP journalist Mila Shevchuk, Olena shares how a team of four people with no prior experience in social projects or the restaurant business managed to quickly open hostels for displaced Ukrainians, what inspired them to launch a concept restaurant, how many litres of borscht they sell in a day (and why it sometimes disappears from the menu), and the unique challenges of working with Ukrainian cuisine in Poland.

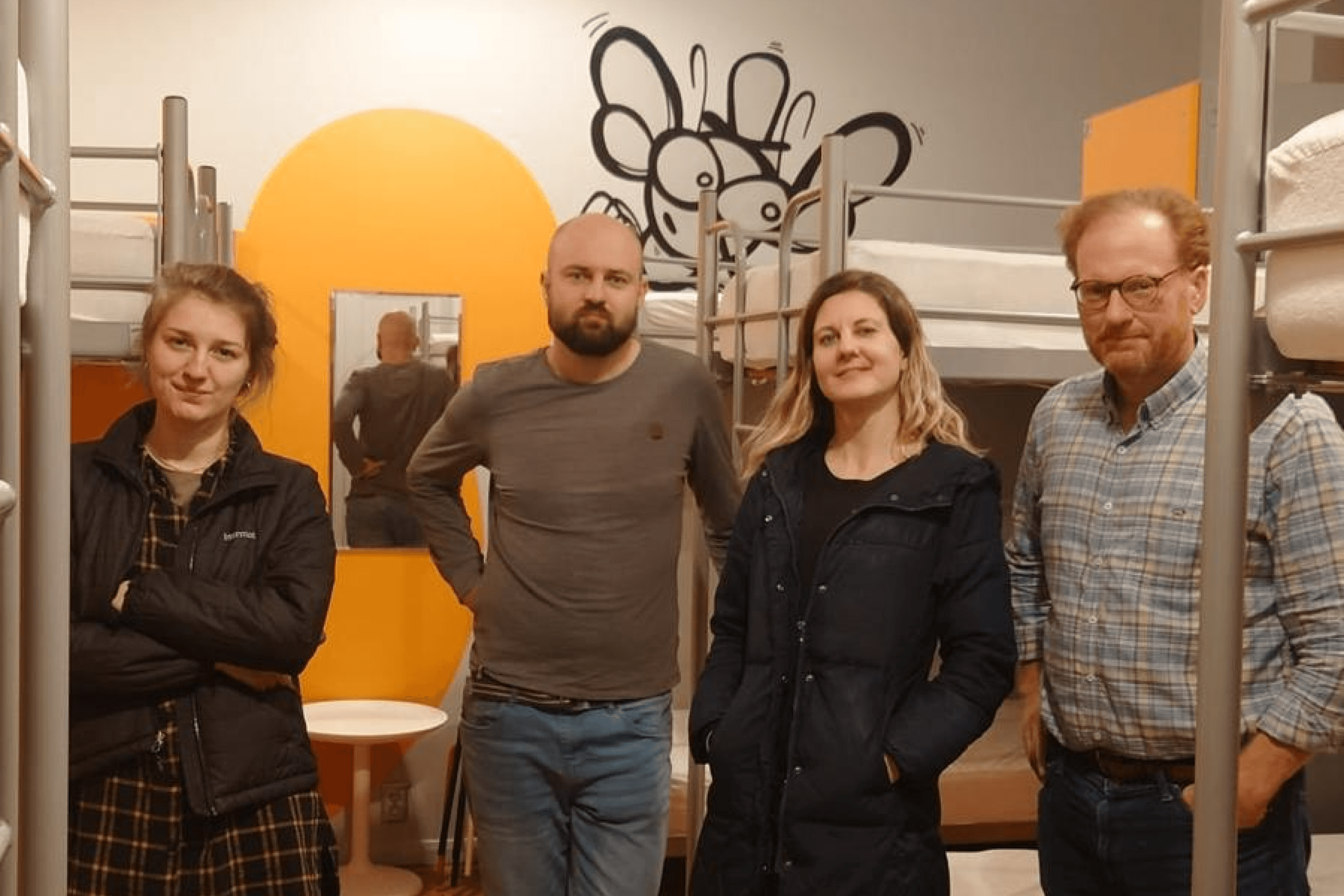

She studied urban planning and spent six years in Poland, working in her field. In 2021, she returned to Ukraine. But after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Olena brought her two young nephews to Poland and stayed on to volunteer at the border. Using her own funds, she arranged overnight shelter for Ukrainians crossing into the country. When the money ran out, she turned to social media to find a way to keep going. She soon joined the team at ZeroCamps, a foundation created by Polish IT entrepreneur Mateusz Zguda, supported by funding from his American friend Hewitt Strange, with Maryna Kliushnyk providing organizational support and maintaining direct contact with refugees. The foundation provided shelter to more than 3600 Ukrainian women and children in its hostels across Krakow.

Later, the team decided to further integrate these people, leading to an experimental social project — a Ukrainian home-style restaurant in the heart of Krakow that is still staffed exclusively by Ukrainian women.

What is your education and work experience before this restaurant story? Did you have any prior experience in charity work, and how did you get involved?

I am an urban planner. I studied in this field for 10 years and worked in Poland, where I lived for six years. But I wanted to return to Ukraine. In the fall of 2021, I came back home and launched my own project in the Carpathians. After the full-scale invasion, I took my two young nephews to Poland. Since I knew both languages, I began volunteering right at the border. Friends offered me a house, and for two weeks I brought people there to stay overnight because at that time, there literally wasn’t room even for those who could pay. But I ran out of my own money and started looking for ways to continue this work — without starving in the process. At that point, all my capital was tied up in Ukraine and I wasn’t working on anything else. So I simply found an opportunity: a very similar project, but it was privately funded. That’s how the Zero Camps foundation was born. Its goal was to ensure that people didn’t have to spend nights at train stations or camps, but instead had decent conditions, at least temporarily, where they could feel safe and figure out what to do next. This was cooperation, not volunteering. Of course, no one worked just eight hours back then — if not 24, then at least 12.

The foundation is made up of four people. The initiative was started by a Pole, Mateusz, and supported by Hugh Strange from Charlton, USA, who was the main fundraiser. Marina and I, both Ukrainians, handled the organizational aspects. Mateusz Zguda lived in Krakow and owned an IT company there. He saw that Krakow’s train stations were overcrowded 24/7 with Ukrainian refugees and decided to help. He brought mattresses to his downtown office and helped transport people from the stations. He posted about this on LinkedIn, and Hugh saw the post and said, “I have people with funds. This needs to be organized properly.” They understood they needed Ukrainians on the team. Marina left Dnipro for Poland, where Mateusz helped her settle. They met, she told she had experience working with people, had organized scouting for children, and had the aim to help her compatriots — so Mateusz invited her to join the team. They needed someone fluent in both languages to communicate with Ukrainians and Polish authorities. He posted on Facebook that he wanted to set up a foundation. A friend of mine shared the post, I reached out to him, and we joined forces. Within a day, we rented our first hostel just five minutes from the train station; two weeks later, another. Then we added three apartments in Krakow and one house, allowing us to provide housing for about 150 people. We managed to do it all within a month thanks to financial support from Hugh and Mateusz handling the legal side.

Krakow is one of the most expensive cities in Poland. How much did it cost to run one hostel?

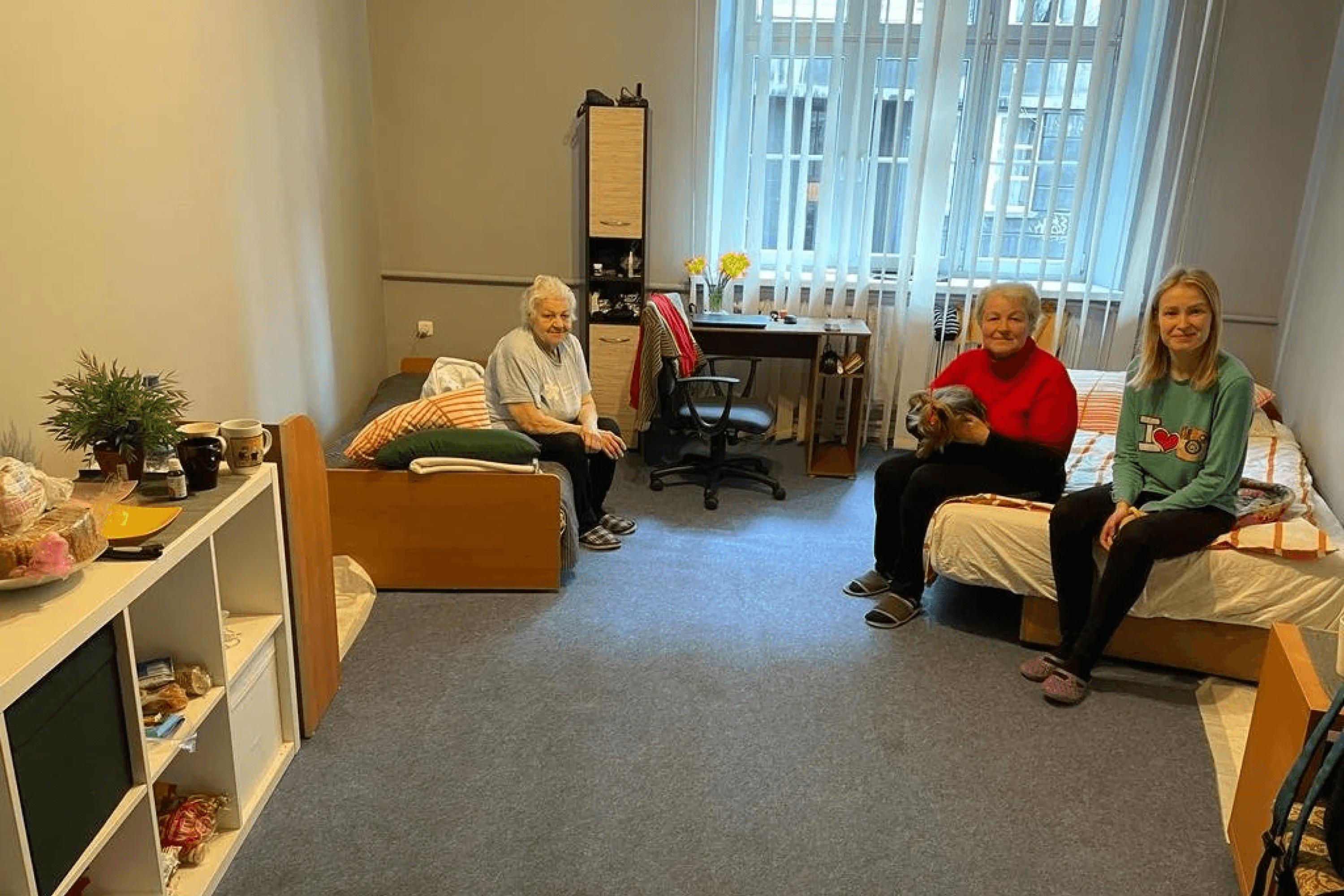

We closed the last hostel in September 2024. I remember the rent for one hostel was around 20,000 zlotys, about $5,000 a month, not including utilities. Poland has a complicated system — you can’t really predict utility costs, and you often end up paying extra. We also provided food from the very beginning until closing the hostels in 2024: we made weekly purchases according to hostel residents` lists of needs. Mateusz calculated that more than 3600 people stayed in the hostels. We had no experience in the social sector and learned as we went. At first, the idea was just to provide temporary housing, but then we realized many people weren’t able to move on and needed to stay longer. At the same time, they weren’t integrating and were just waiting it out. So after six months, we started charging a small fee for those staying long-term. Everyone can earn this, even if they have two kids and can only work part-time, like twice a week. But we wanted people to get out there and engage.

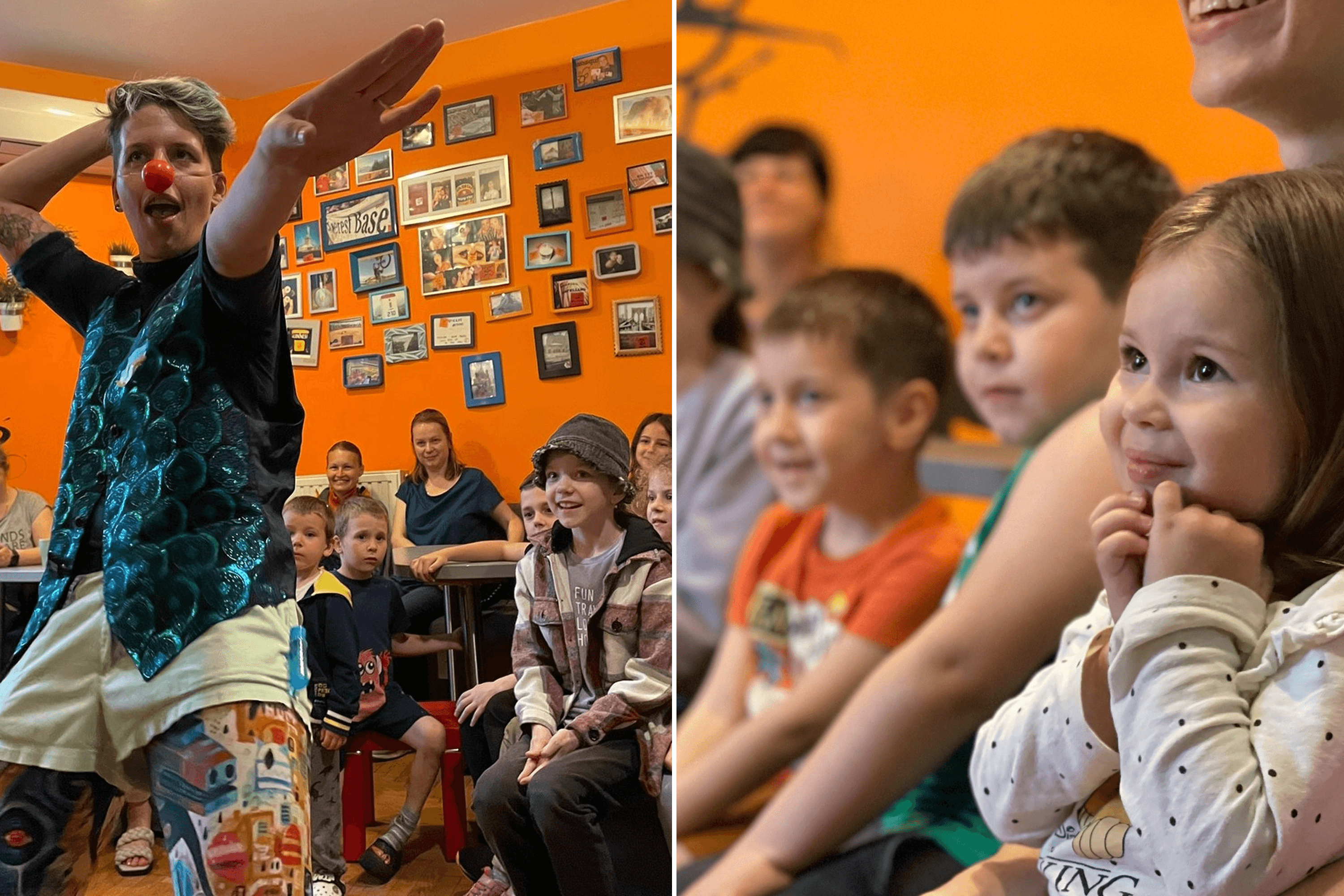

We all noticed one thing: the women cooked a lot and were eager to share what they made with others. It was Ukrainian hospitality shining through, even in such difficult circumstances. That’s how the idea of opening a home-style kitchen came about — a place that could be their first workplace and help them get back on their feet, while we shared our kitchen with them. One reason we began considering this was because we received additional funding from the Polish government, which we invested into Ciepło. It was the standard subsidy of 40+ zlotys per person — a popular program in Poland to support community organizations hosting displaced people. With that funding, we wanted to take the next step in offering help.

Who on your team first came up with the idea for the restaurant?

It was Mateusz who said it would be great to open a home-style restaurant in Krakow. As someone in IT, he saw this as one of the biggest problems of modern life — not having easy access to comforting, home-cooked meals when you’re too busy to cook. The idea was his, and so was the name Ciepło, which was meant to evoke the warmth of home. Around the same time, Hugh had a baby and continued helping with fundraising, but after a month or two, he stepped away from the day-to-day organization of the foundation. So it came down to the three of us — and I was the only one who opposed the idea. I had friends in the restaurant business and knew how difficult it could be, how it can take up all your time. I also instinctively knew it would end up on my shoulders.

How did things progress from there, and how did you ultimately become involved?

Maybe it was ambition, a feeling like “let’s try and see what happens.” It was exciting, a new experience. Then I connected it to a personal need. I missed home and really longed for my culture. In Poland, Ukrainian cuisine is presented in a strange way: either at a very high level in Warsaw, in luxury restaurants without a true Ukrainian idea, or with white walls, sunflowers, and embroidered towels, serving pelmeni, chebureki, and everything all mixed up because some people came from Kazakhstan, some from Belarus, and some from Ukraine.

My Polish friends often asked me for chebureki or pelmeni recipes, and I said that’s not all of Ukrainian cuisine — it’s very diverse and delicious. In my mind, I had a clear picture of how it should look and be served, and what we definitely wouldn’t present. We still don’t have pelmeni on the menu. There was also the issue of dishes linked to the Soviet era, like vinegret salad and liver cake, but we chose to keep them because they’re part of our childhood and our parents. Ultimately, they give Ukrainians a feeling of home and bring back emotions.

What else is deliberately missing from your menu or service?

From the very beginning, we absolutely did not serve in Russian — that was never up for discussion. We took a long path: we didn’t use our flag’s colors or coats of arms on the signs because we understood this was a very temporary situation. Back then, those flags were everywhere, and every new business used them to show they were from Ukraine, which was an easy way to attract customers. We decided to go with the Polish name Ciepło. At first, many Ukrainians passing by came in, surprised to find it was a Ukrainian spot. Why not call it “Ukrainian Taste” or “Ukrainian Cuisine”? Why not use Ukrainian language or display the flag? Every choice was deliberate, carefully planned, and intentional.

How is your restaurant officially structured — is it a social enterprise that generates profit under a charitable foundation?

We opened the restaurant as an association under the foundation. The foundation didn’t open it directly but is the sole shareholder of the association because associations can generate income. That income was intended to support the foundation’s goals — helping Ukrainians. However, we closed the hostels before the business took off. That was also an illusion of those who lacked experience. The restaurant business is tough, especially in a country where the minimum wage changes every three months. At Ciepło, I’m also an employee. Within the foundation, we were on the board. At Ciepło, Mateusz serves as president, and I was responsible for day-to-day operations. I didn’t personally hold any shares — I was a co-founder. The foundation ownes 100%.

Did the foundation have to invest any initial capital in the company to open the business?

The foundation invested about 300,000 zlotys in the company.

What were the biggest expenses when opening the restaurant?

Rent and supplies. We got the space in September 2022 and opened at the end of November, so it took two months to get ready. A large part went toward kitchenware — we ordered clay bowls, and back then I was still pretty naive. I wanted to source a lot from Ukraine, and we had ceramic borscht bowls made for us in a craft workshop in Chernihiv. Then there were payroll costs. In the first few weeks, people volunteered since we didn’t yet know who would stay on the team, but eventually we had to start paying salaries even before opening. I think we only began making money after six months, maybe closer to a year.

But even so, that’s pretty quick for a profitable business.

People who know the industry say it’s good — it could have been better, but it’s not the worst outcome. We’ve made a profit, but it’s still not stable, and we’re not consistently in the black. Seasonality is a big factor. And the dishes are rich and filling, so summer is a tough time for us. The peak period is when it starts to get colder and around the holidays. We live from holiday to holiday — that’s our season, from Christmas to Easter. Now the season’s over, and we have to keep ourselves afloat. It’s kind of like a game: you make a little profit, then you go into the red again.

What was the hardest part of the official opening?

On opening day, the health inspection wanted to shut us down. It’s on the ground floor of an old building, a tenement — there’s ventilation, everything meets regulations because we took over a place that had been a restaurant before and didn’t change anything. We weren’t responsible for the smell bothering the residents. But because the chimney system was faulty and too narrow, the smell got into the apartments. And since we were doing full cooking, including meat dishes, there were strong odors. The neighbors filed a complaint against us, and the inspection came at that very moment. It turned out that some certificate was either outdated or missing — the owner and I were figuring it out. We didn’t even know this could happen. They told us to only prepare salads and sandwiches. But it was opening day! So officially, we were closed until 4 p.m., but at 6 p.m. we had the official opening, we worked at our own risk.

Hadn’t you already been operating for a few months?

We were just getting started with a short menu: two or three cold appetizers, five main courses, two desserts, and three soups — and even that felt like a big deal for us. When we opened, it was about 50% of what’s on the menu now.

How difficult is it to handle permits and bookkeeping in Poland?

We took the space without a license to sell alcohol. It used to be a pub, which really bothered the residents. But we had one condition: we wouldn’t rent the place unless we could at least get permission to serve low-alcohol drinks. We spent about a month negotiating that license. As for the sanitary inspection, the space already had approval — we didn’t have to redo anything. The bookkeeping was handled by the same firm that worked with the foundation and Mateusz’s IT company. They’d been on the market for a long time, had a solid reputation, and we simply chose people with experience.

Does your profit have to go entirely to the charitable foundation?

The profit is supposed to support the foundation’s goals as outlined in its charter. But that only applies once it reaches a certain level — we’re not talking about 2,000 zlotys. The business also has to contribute to a risk fund. For now, any profit goes toward covering a rougher month or season ahead. There hasn’t been enough yet for this project to generate another one, the way the foundation led to Ciepło.

You said you initially struggled to find a space. What budget did you first plan for — rent or purchase — and how did it turn out? Since your location is central.

We weren’t sure if this would be a neighborhood story, home-style cooking in a residential area with one concept, or a central spot where we’d dive into the culture, which would also interest tourists. I had my own vision, but we followed the foundation’s goals. We were aiming for around 3,000 to 5,000 zlotys depending on the area and the type of odstępne. In Poland, you have to pay the previous owner for any renovations done or for things like an extractor fan. In the end, our rent is 12,000 zlotys. Plus utilities, that brings it to about 15,000 zlotys.

And who took care of setting up the space?

Me.

You mentioned the lack of Ukrainian branding, but by one table there’s a wall that says “Greetings from Mariupol” and other cities.

That happened quite organically. The place has branding — a logo, the colors we use, and our font “Misto”, created by a Ukrainian designer. Mateusz’s wife, who owns her own graphic design firm, helped make it. Conceptually, we chose a style somewhere between urban and ethnic. I understood that without ethnic elements, you can’t really show the culture or catch attention. But the renovation was already done, the tables and bar were there. We didn’t have the money to redo everything, nor the time or energy. We had to work with what we had and add our own touch. That wall was painted with magnetic paint. At first, it was our kids’ corner. People came with their children, sat there, and Ukrainians wrote about their hometowns. That’s how the wall became covered in writing.

How did you select the women? Are they all still Ukrainian?

Since we opened, only Ukrainian women have worked here. At first, it was mostly those who arrived after February 24.

Were those women only the ones who lived in your hostel?

No, although that was the plan. Our hostels were a great source for staffing, but waiters needed to be young people who spoke three languages. We had to present the concept — foreigners and Poles came in, and we needed to explain the place and its culture to them. So, we began looking for students who arrived after the full-scale invasion, had learned Polish, and spoke English. We didn’t have such people in our hostels. However, we did hire some from the hostels for technical support, kitchen help, and dishwashing. There were cooks, but not all had enough experience — we needed people with stronger expertise in professional cooking. Just because the women from the hostels could cook didn’t mean they were ready to work in a restaurant. They needed to know the technical processes, how to cook for large numbers, and how to manage that. So, we hired people with experience.

The hostel experience showed us that, although staff turnover is common in restaurants, it became even higher when we hired people from hostels because they were waiting to return home. We didn’t take that into account when we came up with the idea. We hadn’t considered that some might leave after a month or two while the restaurant was already up and running. After that, we began mixing the team. Now, only one woman from the hostels is still with us — she makes varenyky — along with a few others.

How many people currently work at the restaurant?

The number varies between 13 and 15.

Considering Polish taxes, how much of the turnover goes to salaries?

The person managing the business estimates how much salaries should take as a percentage of turnover. Here, it’s sometimes around 60%, which is quite high.

What’s the current minimum wage in Poland, and how does that compare to what your employees earn? Do these women earn more than or about minimum wage?

Poland’s minimum hourly rate is currently 30 zlotys and 50 groszy gross. It depends on how many hours and shifts they work. For cooks working full time, between 140 and 155 hours — since kitchen hours can sometimes be longer than office hours — it’s not minimum wage, our average salary is $1,400 per month.

So they can all obtain their documents and work residence cards?

Yes. When it comes to documents, my co-founder Marina and I were on the worst kind of temporary status. The whole paperwork process during my first stay in Poland was very draining. And having those documents prevents you from leaving the country for a while. That didn’t work for me. I was never interested in citizenship or permanent status, but I understood that others needed it. We made sure they had everything they needed to sort out their own paperwork.

What kind of menu did you open with, and what is it like now? Has it changed?

Of course, it has changed! When we first opened, for the first three weeks, we served Poltava-style varenyky, syrniki, borscht, and to be honest, maybe some ribs — so about three or four main dishes. We also brought in Carpathian teas and Lvivske beer at that time. I remember people coming in, and we told them it was a temporary menu because we were still developing it. We actually worked on perfecting the borscht for two weeks since every cook has her own recipe; we adjusted it to a version that would suit everyone. It’s truly a handmade, crafted story. Now, our regular menu includes four appetizers, like forshmak, salo with rye bread, and eggplant rolls; three salads, including one with veal cheeks; and three types of borscht — red borscht made with ribs, garlic, and pampushky, a vegan red borscht, and green borscht with egg. We offer ten main dishes, including Poltava varenyky, pancakes with chicken and mushrooms, and fried varenyky. For dessert, we have crepes with poppy seeds and nuts, homemade Napoleon cake, syrniki with sour cream and homemade jam, and Lviv-style cheesecake — desserts priced between 24 and 29 zlotys. Previously, Ciepło opened around noon or 1 p.m., but now we’ve added breakfast from 9 a.m. to 1 p.m., featuring savory and sweet syrniki, oatmeal, eggs, and sausages, with prices ranging from 17 to 44 zlotys.

What are your most popular dishes right now?

It’s borscht, sometimes we sell up to 150 liters with pampushky and salo. It basically fills our entire menu. Anyone in the restaurant business knows some dishes can’t be included because they overshadow others. We can’t remove it since it’s our signature dish and calling card. Borscht is very filling and some people don’t want to eat anything else after having it. Sometimes we joke about just selling borscht. That said, doing so would stray from our concept of offering diverse regional dishes since people mostly come for borscht and varenyky — which taste just like mom’s or grandma’s.

You mean you made and sold 150 liters of borscht in a day?

On weekends, yes, it could be 150 liters a day. On a typical day, it’s a lot less — we just wouldn’t be able to keep that pace up all the time, it’s simply not realistic.

What are your top-selling dishes after borscht? What are the three most popular items?

What are your top-selling dishes after borscht? What are the three most popular items? This Easter was the first time borscht didn’t top the sales. Instead, chicken Kyiv, ribs, and nalysnyky led the way. Chicken Kyiv and varenyky are always among the favourites. These days, the average bill is about 100 zlotys, with guests typically spending around 60 per person — though that depends on group size and how many dishes they order.

What are your personal favourites from the Ciepło menu?

I get why people love borscht. I’ve eaten it often myself. But I also really like kulesha — when it was on the menu, I ordered it all the time. Nalysnyky, of course. And chicken Kyiv. I love Ukrainian home cooking, so even a simple beet and carrot salad with sesame tastes better to me than ramen at a Thai place. Maybe that’s why I’m doing this project.

What’s the current breakdown of your guests? Are most still Ukrainians, or is it mainly Poles and foreign tourists now?

We started out with around 70% Ukrainians and 30% Poles and foreigners. Now it’s shifted — Poles and international visitors make up about 60%. Maybe it’s because we’ve built up more reviews on Google. Tourists don’t usually go somewhere they haven’t seen online. And now we’re more visible as a Ukrainian restaurant. In the beginning, for some reason, we weren’t even showing up in search results.

When you first opened, what kind of promotion did you do, and what about now? Is it mostly word of mouth and Google?

Promotion has always been a weak spot for us. We tried running targeted ads after two years, but it was just too expensive. Between the specialist’s fee, the ad budget, and the need to run it for months, we couldn’t keep up. So we mostly rely on word of mouth.

How many seats do you have altogether? And when you say traffic has grown, roughly how many guests did you serve per day back then?

Weekends were really busy, with lines outside and people waiting for reservations. Borscht sometimes took 50 minutes to serve. I usually don’t focus on numbers, but even during early spikes two years ago, we had fewer weekend guests than we do now, which is a good sign. Inflation is also a factor: every three months, prices for food, electricity, and minimum wage rise. One of our biggest challenges is when people say home cooking shouldn’t cost this much. Our priciest dishes — stuffed Chicken Kyiv, veal cheeks in wine sauce with new potatoes, roasted ribs with country-style potatoes, and pike-perch fillet with grilled vegetables — cost between 56 and 59 zlotys (about $15 to 16). These dishes require full preparation, which is why the industry is shifting toward fast food, where labor costs are lower and processes simpler. Full cooking like frying Chicken Kyiv, baking ribs, or simmering borscht means higher costs. People enjoy the pampushky and bread we bake ourselves, along with cheeses and sausages made in-house, but often don’t appreciate their value. Most bakery items today are frozen or semi-finished, and many assume that if a dish isn’t exotic, it should be cheaper.

How many seats does your restaurant have in total? And what’s the daily guest flow like?

We have 44 seats. On a slow weekday, we might have 40 to 45 guests; on a good day, 60 to 70; and on busy weekends, 150 to 200. But I usually track sales by receipts, not by counting guests.

How often do people get takeout or order delivery?

Yes, we started using delivery platforms about six months after opening. It felt like a good way to get the word out early on. You could call it our version of advertising, even though it’s pretty expensive. You pay a 40% commission and barely make anything on deliveries. That’s why prices are usually a bit higher than in the restaurant — just to cover packaging and other costs. You don’t really earn from it, and sometimes you actually lose money on certain dishes. Still, it helped us get going and brought in about 10 to 20% of our turnover. Now we’re planning to switch to our own delivery through the website to cut down on commission and rely less on those platforms.

What are your plans for expanding or changing Ciepło? How do you see it evolving?

Ciepło has always been a very handmade project. It’s still searching for its final form. We’ve more or less found our audience, though I wouldn’t say completely. I’d love to see more places like Ciepło across Poland. Can we afford that now? Not yet — but it’s something we’d like to aim for. We also want to revive the cultural side. In our first year, we actively hosted themed events, artist collaborations, and evening programs. I used to rotate exhibitions by Ukrainian women artists every six weeks. Now it happens every three to six months. That part slowed down because it became a separate project, and we really burned out during the first year. In our second year, we decided to focus on getting the business side right. Once we’re confident the system works and feels stable and secure, we’ll add another cultural project on top.

What is the biggest challenge for Ciepło right now after two and a half years?

You have to anticipate directions for growth and changes in your target audience. Our cuisine is quite unique in the Polish market. When foreigners visit, they usually look for traditional Polish cuisine. I think the biggest challenge is popularizing authentic home cooking as a whole. Managing costs is also tough. Just when you find a steady path with higher sales and a clearer understanding of your audience, wages go up after a few months. Expenses rise so much that even if you’re doing everything right and growing, there’s always uncertainty about the future because of seasonality in the food business and outside factors. Things like political shifts, whether Trump is in power or offering support, and the complex Ukrainian-Polish history — all of it has an impact.

Have people ever booked events at your restaurant?

We’ve hosted dinners and weddings. Once, we welcomed a Ukrainian-American delegation. The consul personally called me and said, “Olena, don’t worry, this is the consul calling.” I replied, “Why would I worry?” I was so exhausted at that point, nothing could surprise me anymore. That was back in November 2023 — someone had recommended us.

If you were starting over now, what would you do differently?

I would’ve hired a manager sooner. I carried everything myself for too long. And I wouldn’t have spread myself so thin on the cultural side. But then again, maybe without that, Ciepło wouldn’t be what it is today. You need a team that believes in the idea. It’s something you have to do as early as possible. Learn to delegate, stop taking everything on yourself, and find people who can help carry the load.

What would you say to Ukrainians thinking about opening a Ukrainian restaurant in Poland or another country?

I think those are very brave people. You have to go against popular trends, like Dubai-style pasky. Chasing trends all the time is like trying to catch a rabbit. You have to create your own trend — and that’s much harder. One of the toughest parts is that Ukrainian food isn’t exotic or heavily spiced. People often tell us it’s under-salted or under-seasoned. Europeans are used to soy sauces and instant flavor boosts. Marketing is also tricky. You need to figure out how to present this cuisine in a way that highlights its value. Why are you doing this? What’s your purpose? We still haven’t added avocado to our breakfast menu. And whenever we wrestle with that decision, we ask ourselves what our original goal was. Sure, a croissant and coffee would probably sell better. But we keep coming back to that purpose. And this path is longer and harder than opening a café with Instagram-friendly pasky and Dubai-style chocolate.

At this stage, what is Ciepło really about for you?

Ciepło is really about people. I remember getting messages from those unfamiliar with our concept, saying, “Fire your amateur cooks.” Ukrainians tend to be very critical customers and often compare us to restaurants in Lviv or Kyiv. But Ciepło has always been an experimental project with a bigger purpose than just the food. A friend once said to me that this wouldn’t work because no one appreciates real cooking anymore. She said it’s all about ratings, tiny portions, and trendy flavors. No one cares that you can come in at 8 p.m. and get a proper bowl of soup. But we started this based on what we needed, and we’re still holding onto that.