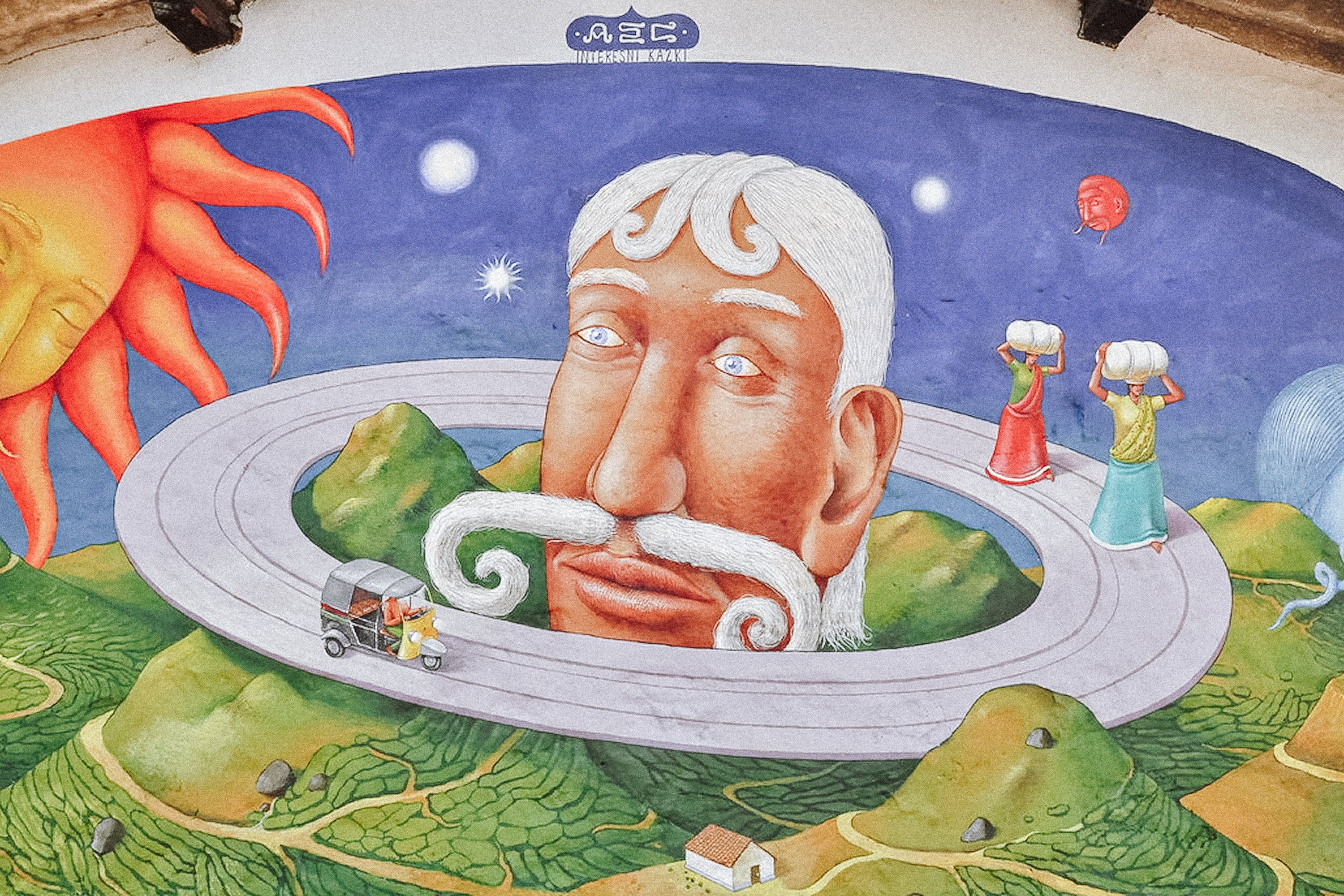

Ukrainian artist Aleksei Bordusov is known internationally as Aec Interesni Kazki. He began his artistic journey on the streets of Kyiv in the late 1990s, alongside the well-known artist Volodymyr Manzhos, also known as Waone.

Over time, his works appeared at festivals and galleries across six continents — from North America and Europe to Asia, Africa, Australia, and Latin America. In 2005, the two artists founded the iconic duo Interesni Kazki, which had worked together for over a decade, creating art that became a philosophical and cultural manifesto. Since 2022, Bordusov has been based in Tenerife, where he expanded from street art and now also works in painting and bronze sculpture at the renowned local foundry Esculturas Bronzo.

YBBP journalist Roksana Rublevska first spoke with Manzhos (you can read his story here), then caught up with Bordusov to discuss the legacy of Interesni Kazki, his solo evolution, and forced emigration.

Aleksei Bordusov, now 45, was born in Kyiv to a family of an engineer and a doctor. He loved drawing from an early age, and after high school, he enrolled in the architecture program at the Academy of Arts. But by his second year at university, Bordusov realized that architecture was too much of an engineering field and what he really wanted was to be an artist. In the late 1990s, he began painting graffiti on the streets of Kyiv and found like-minded people in the Kyiv graffiti club, where he met Volodymyr Manzhos. Eventually, the two formed the art duo Interesni Kazki. Instead of tagging letters like most graffiti artists, they began creating full visual stories — fairytale-like scenes with references to science, global culture, and mythology. Their imaginative style was deeply influenced by Latin American and Brazilian street art. In 2016, the duo parted ways, and both Bordusov and Manzhos went on to pursue solo artistic journeys.

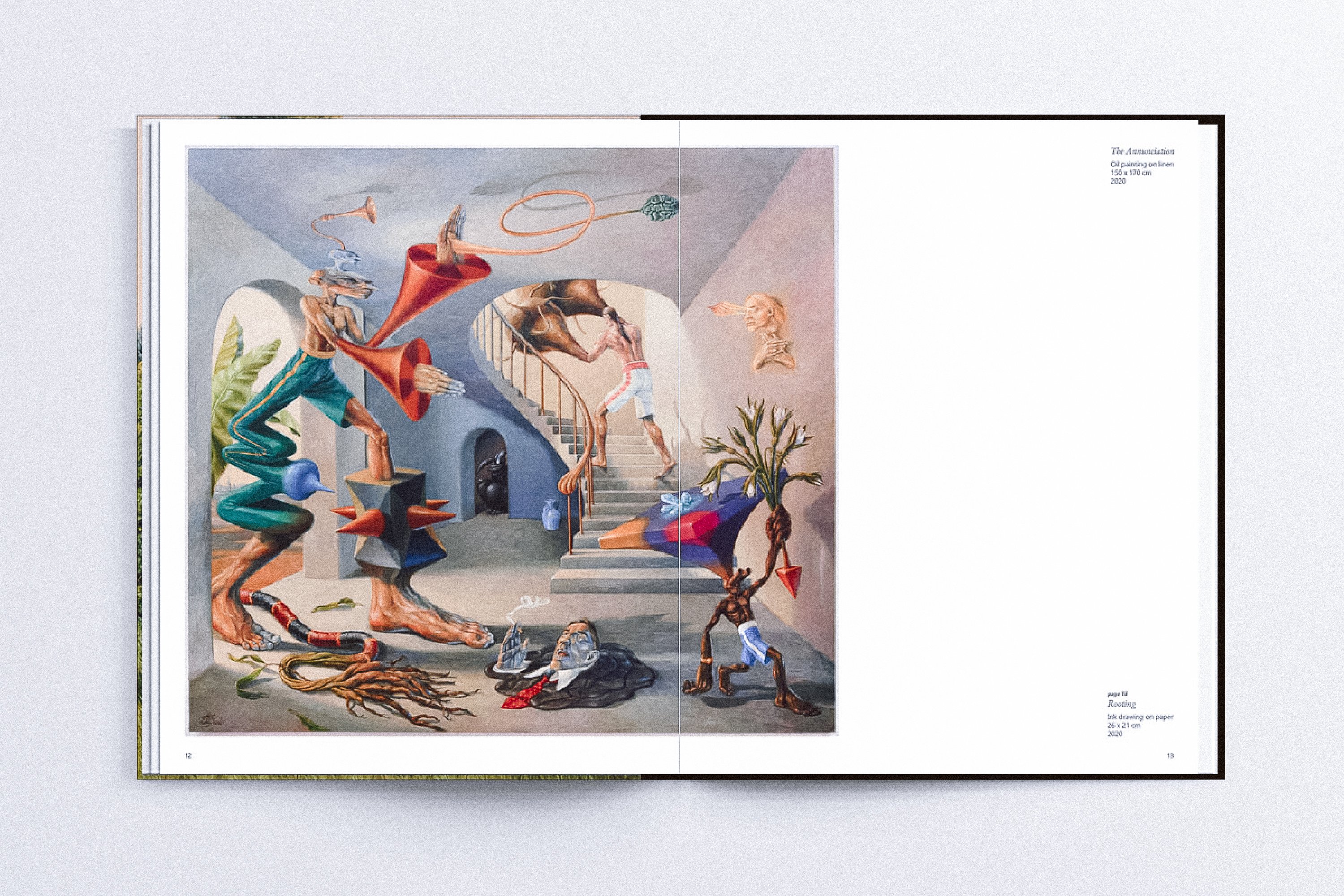

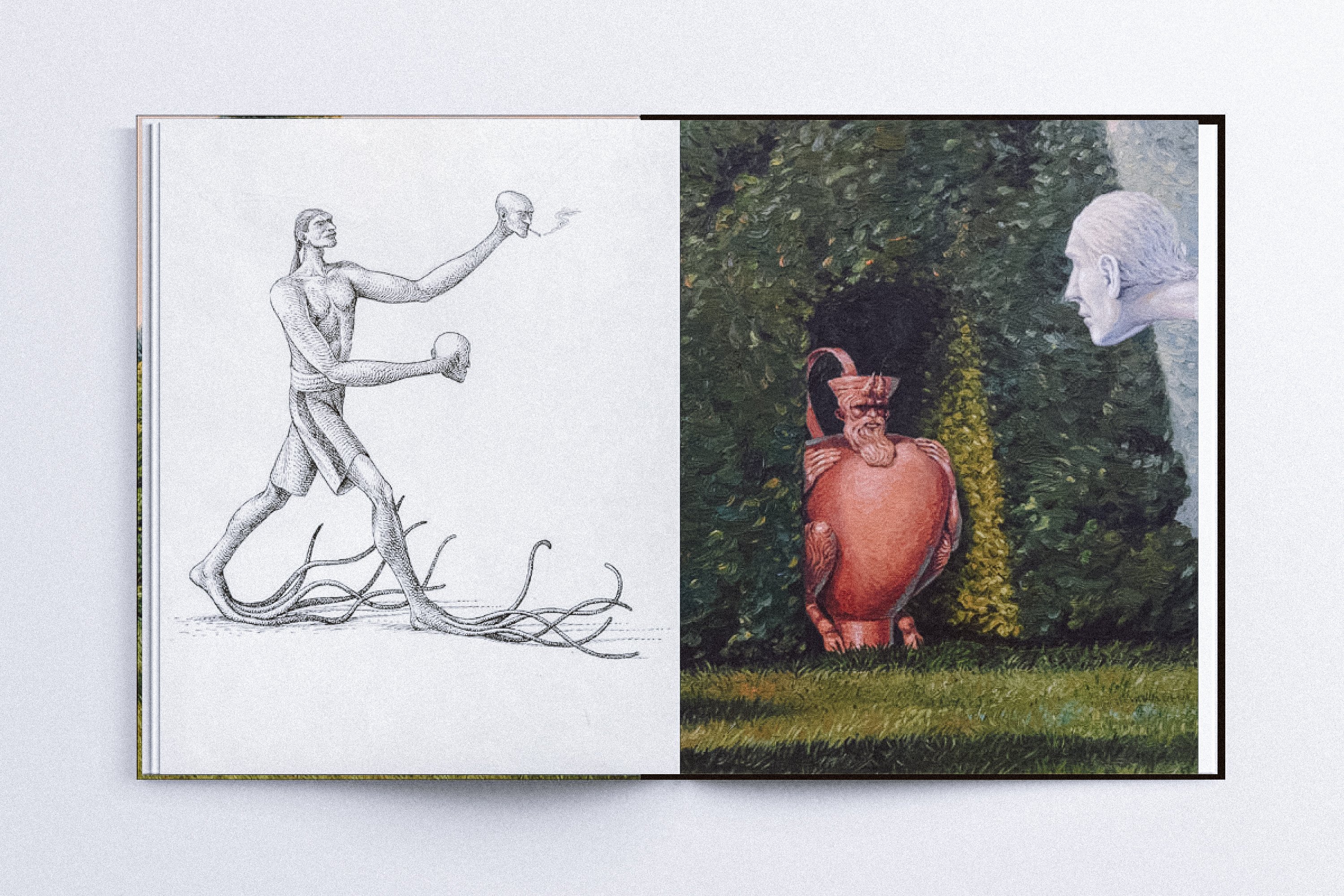

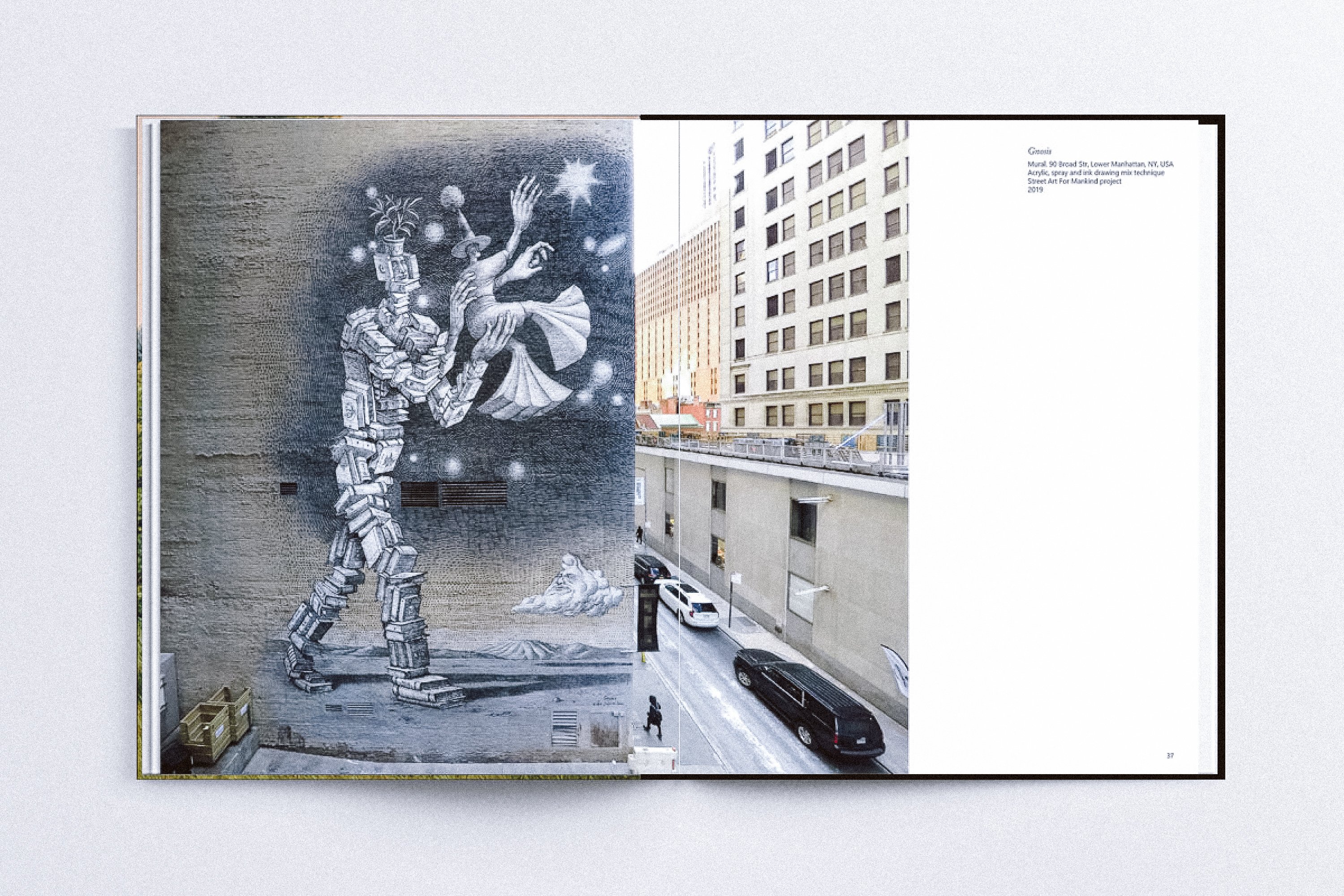

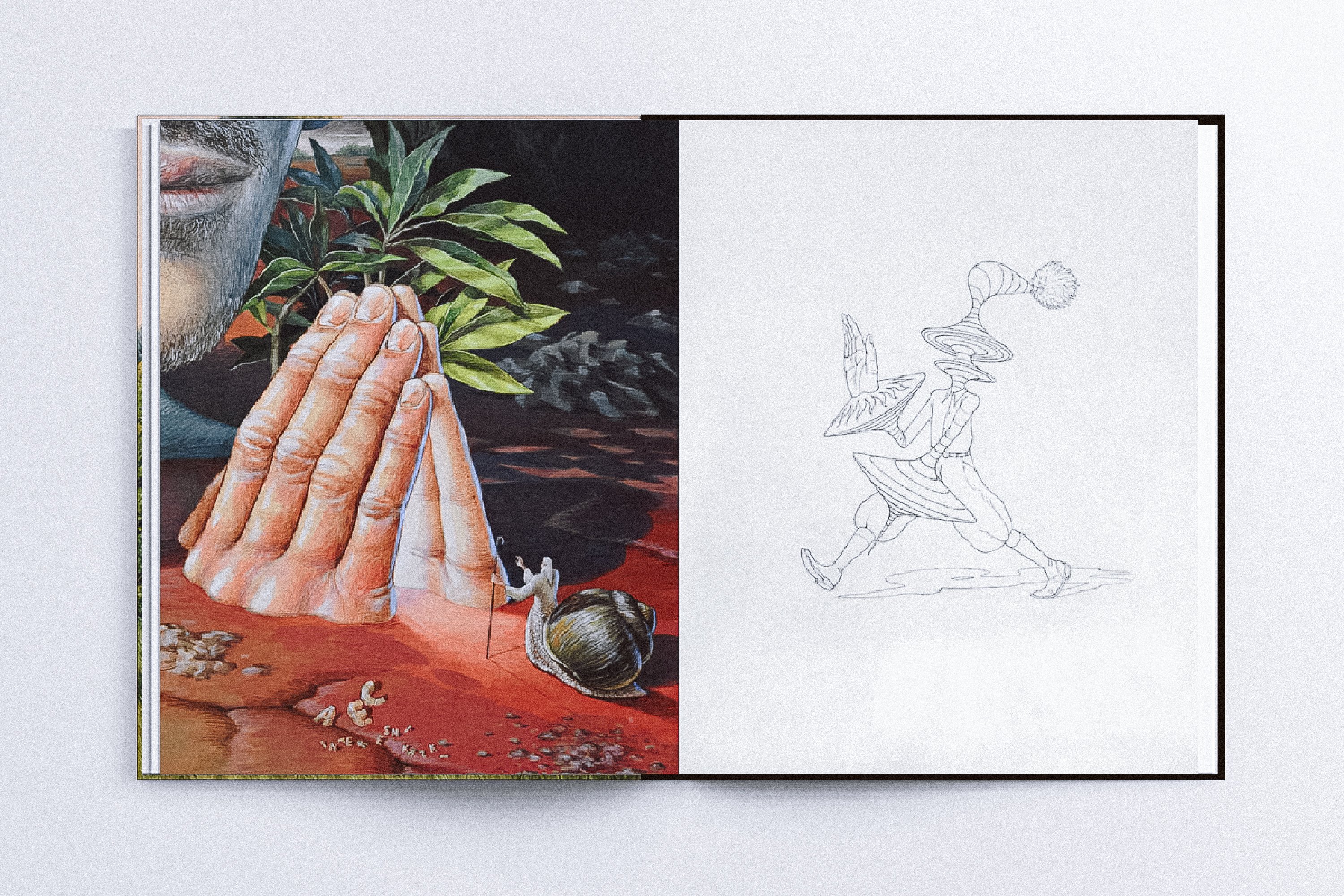

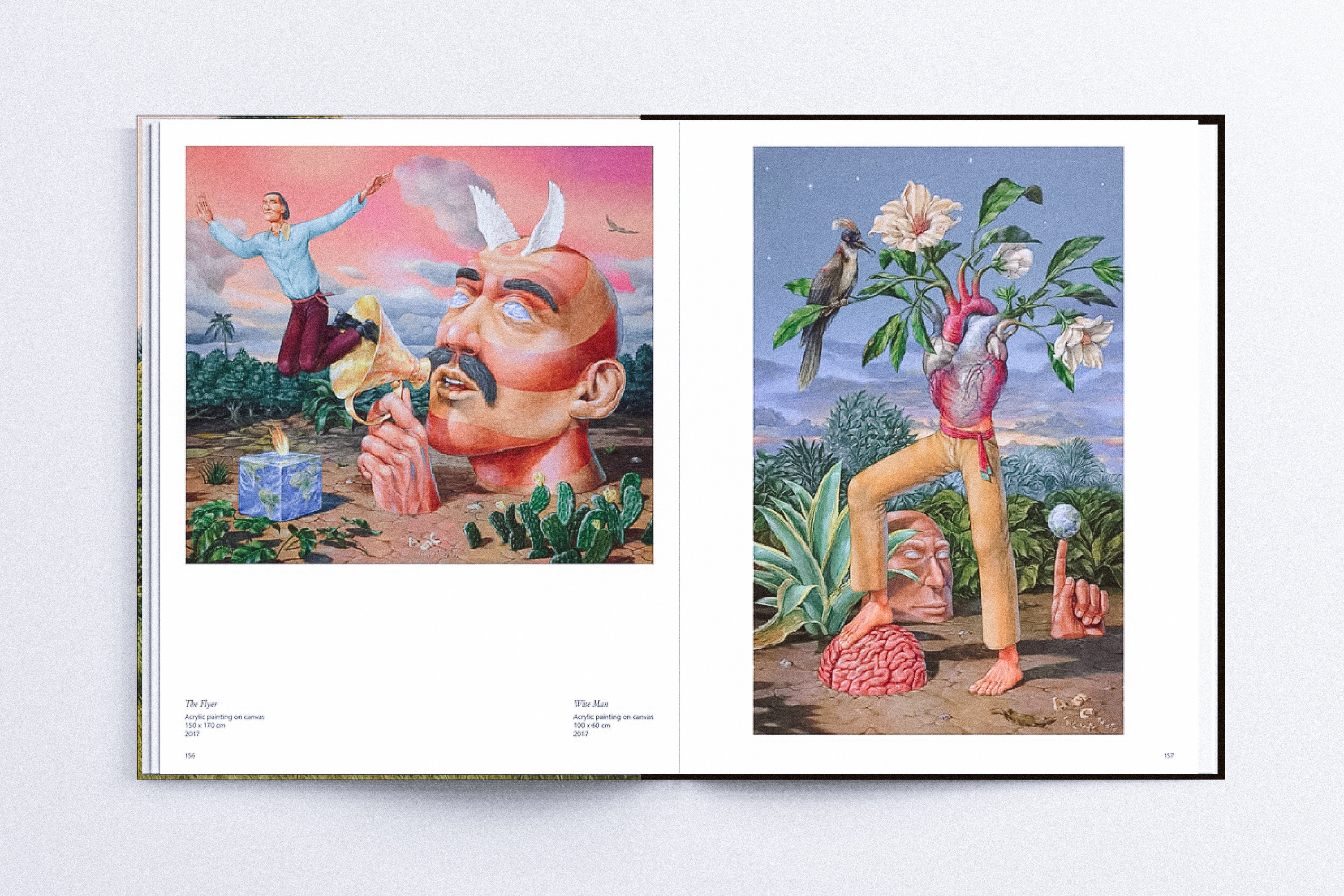

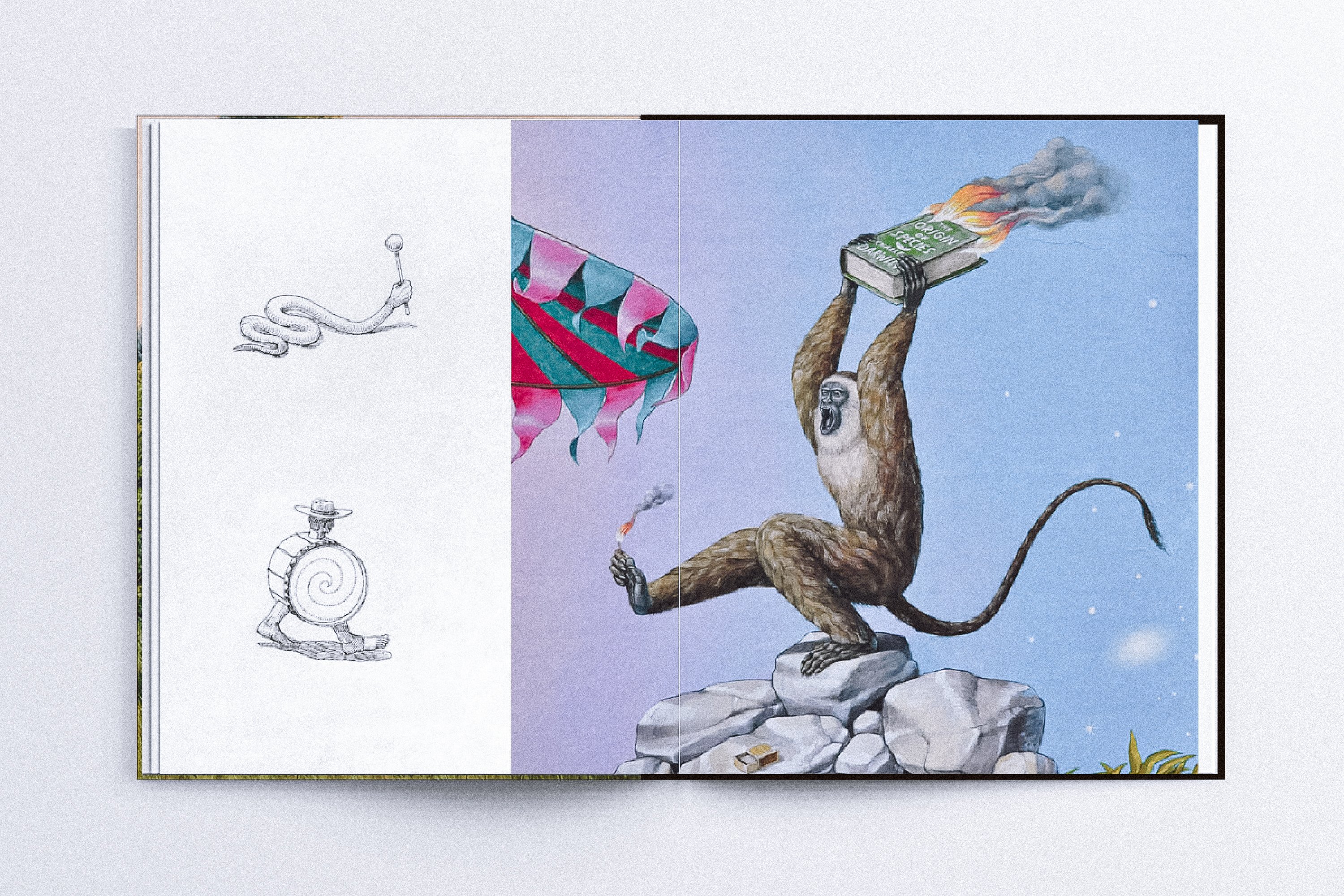

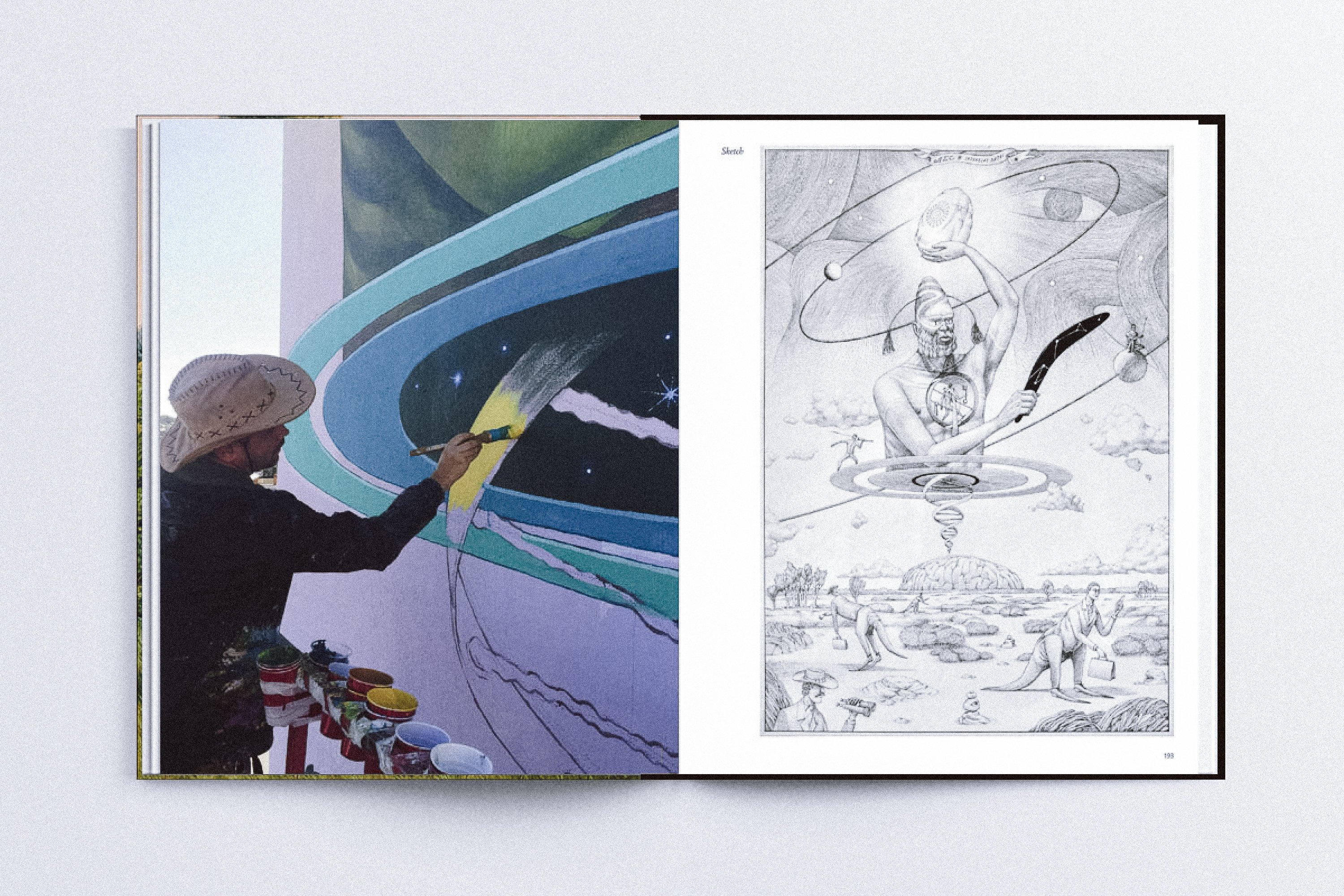

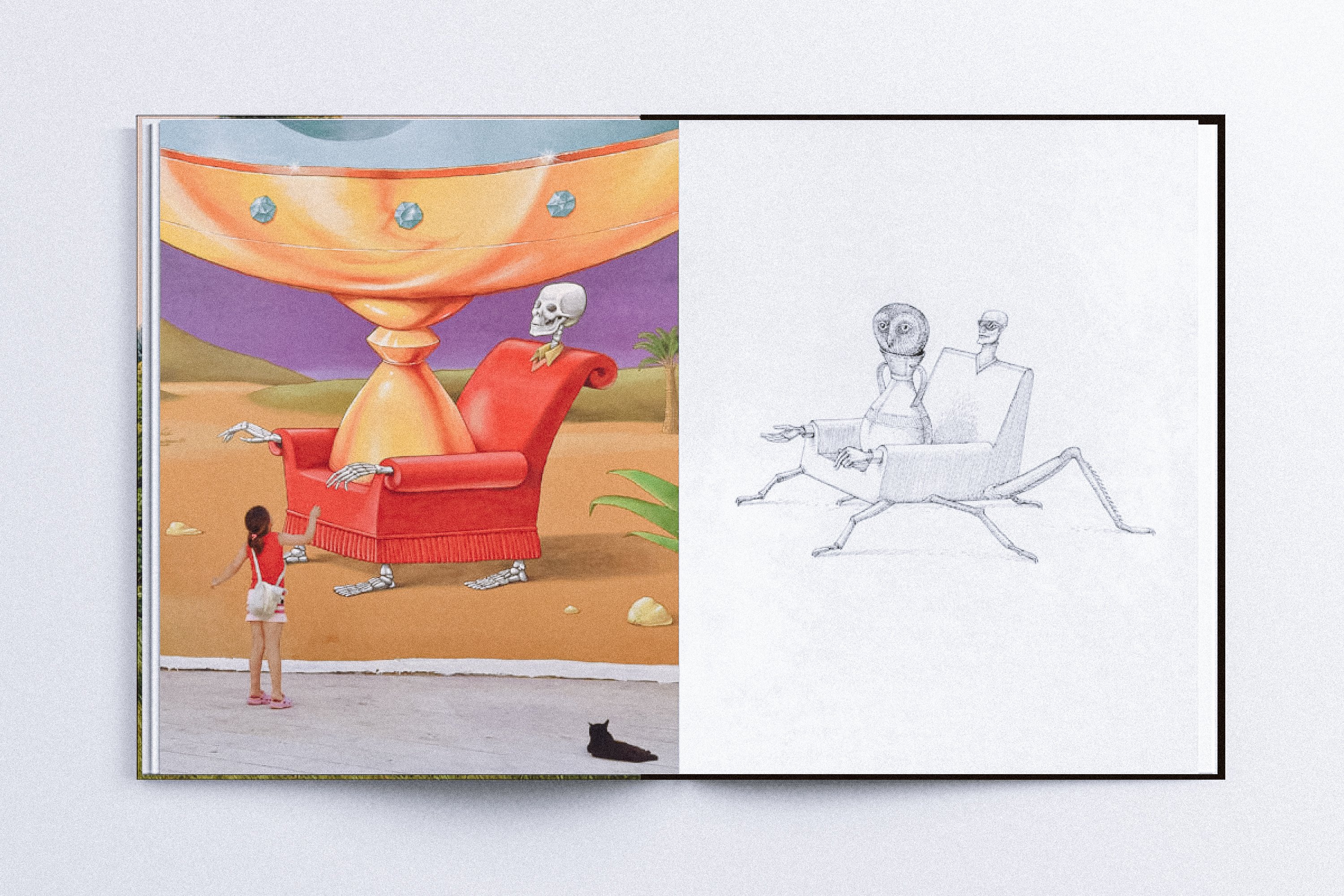

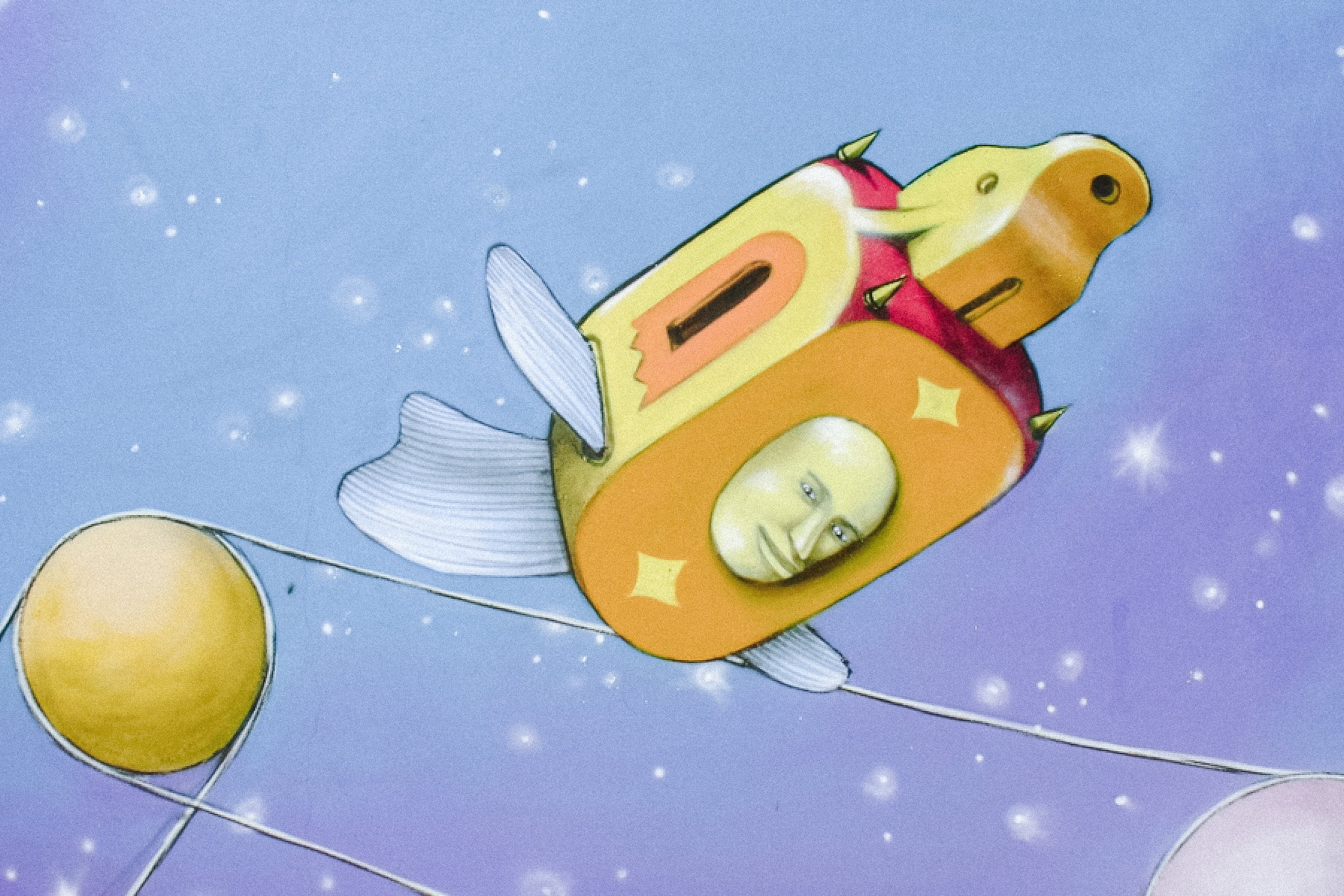

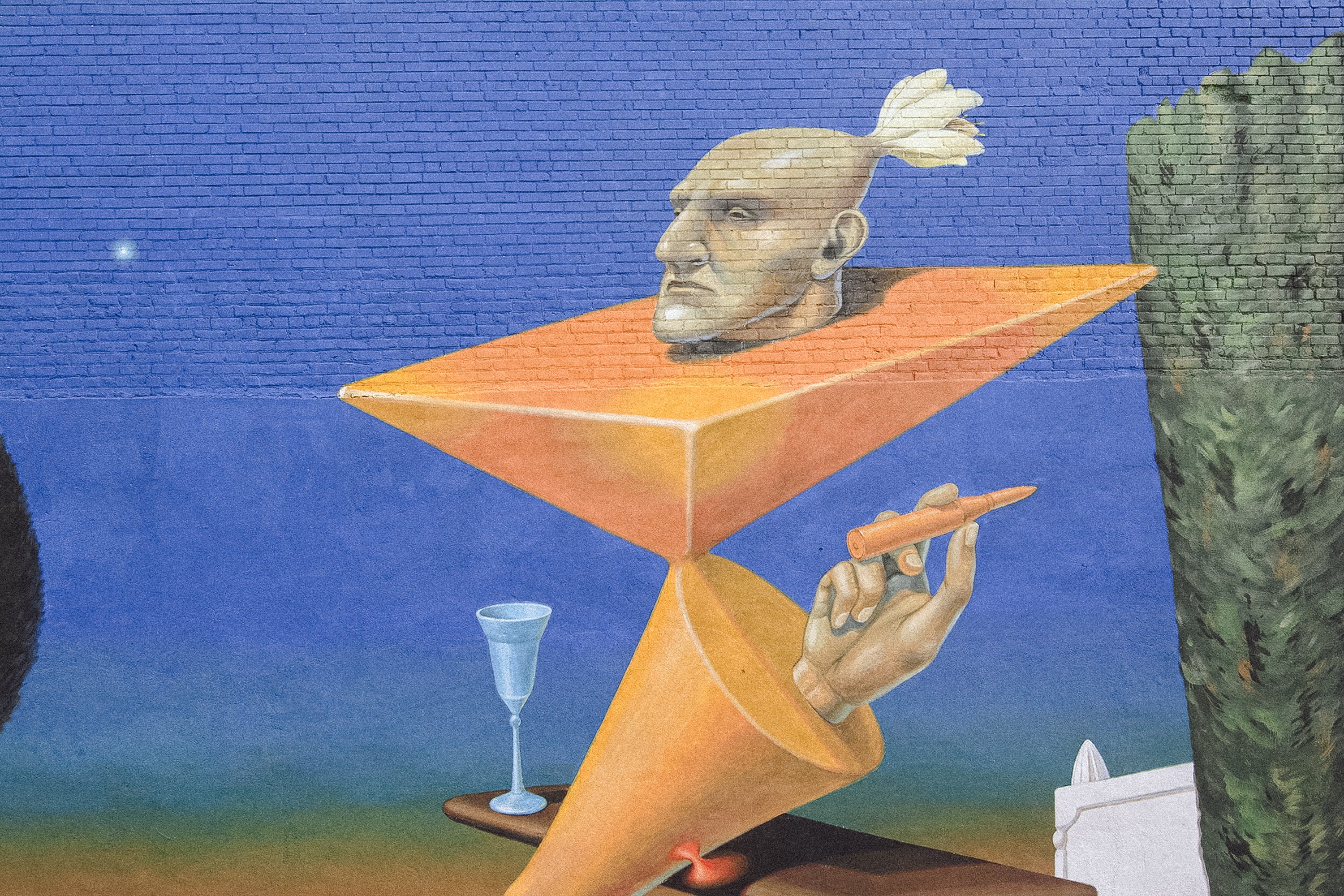

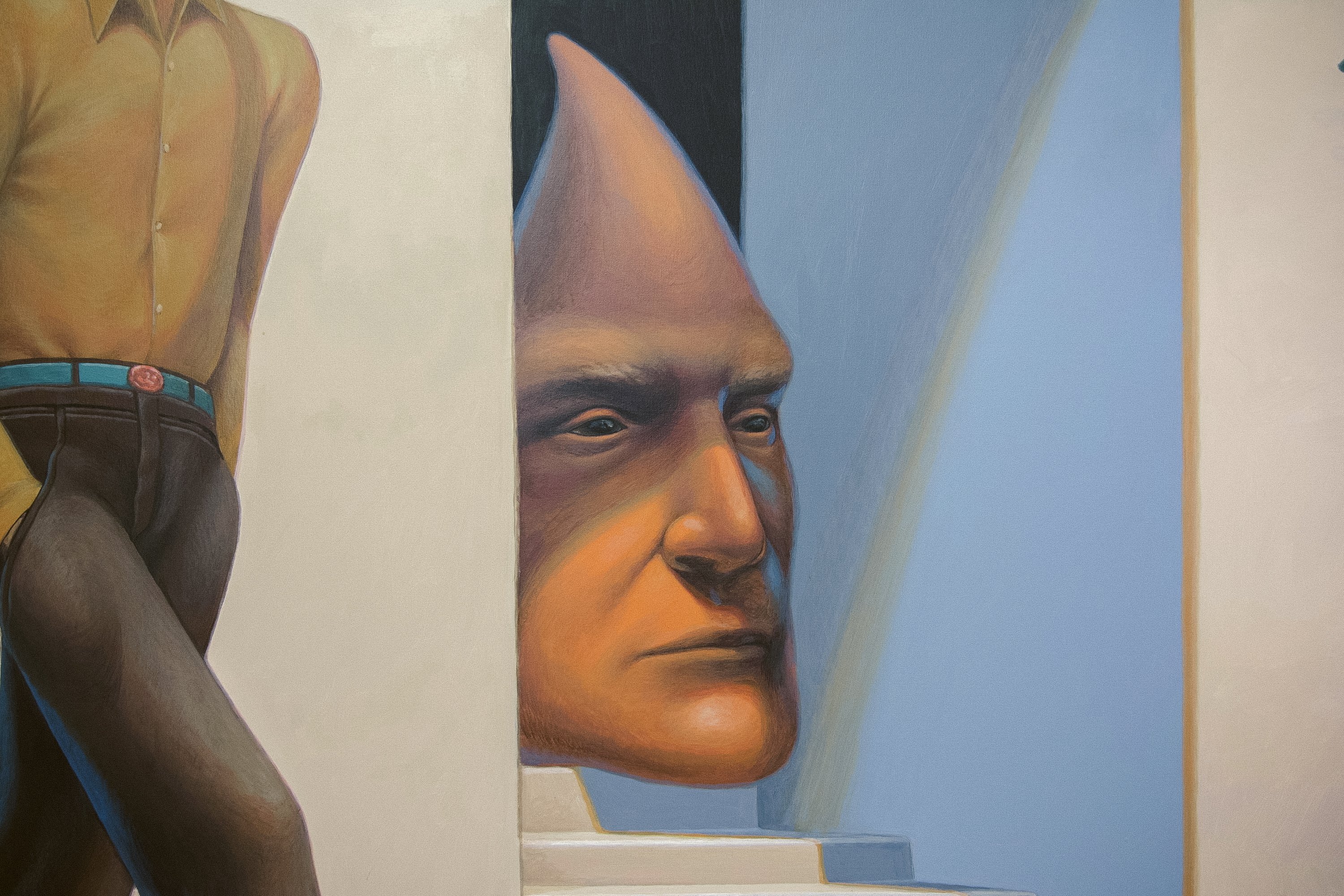

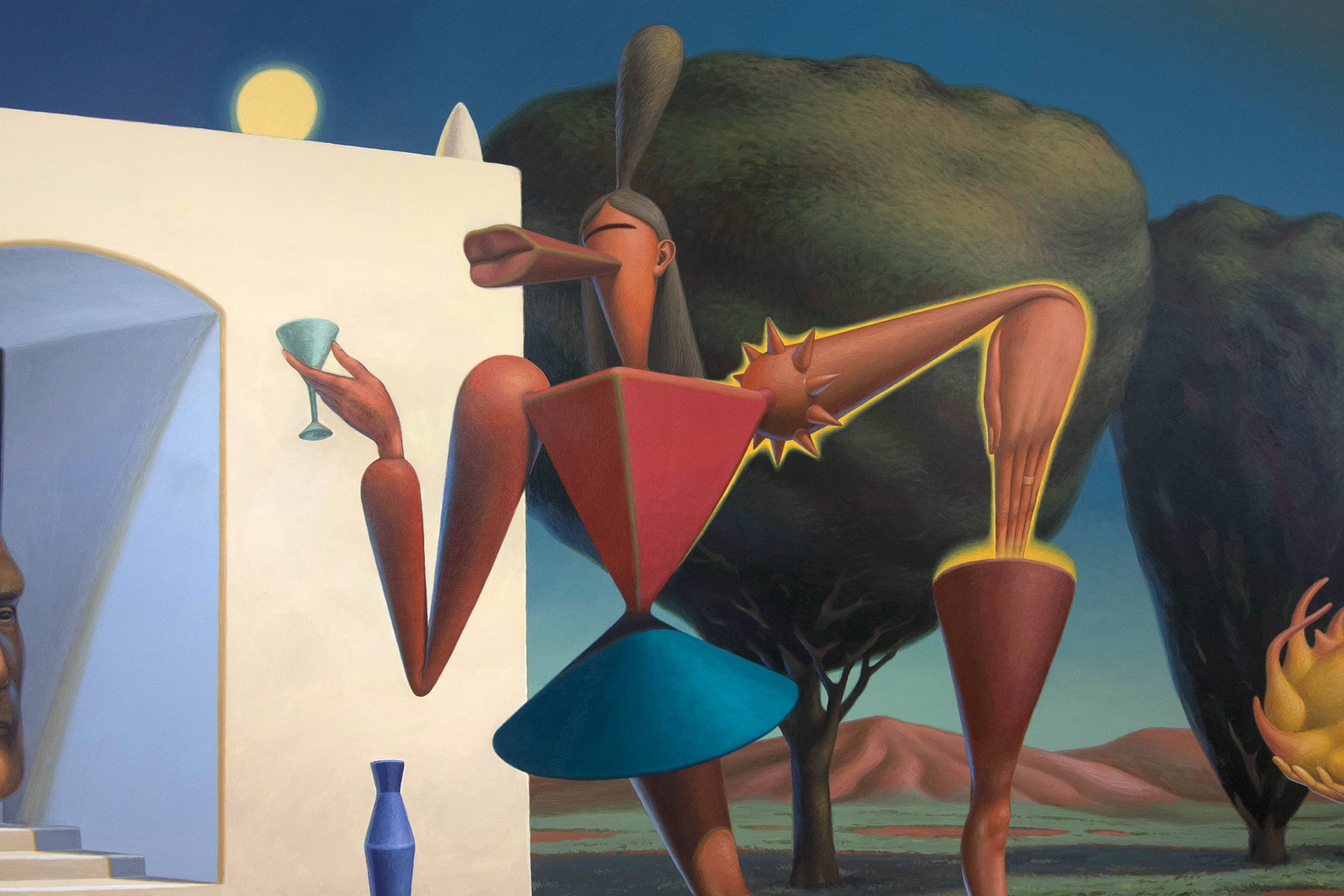

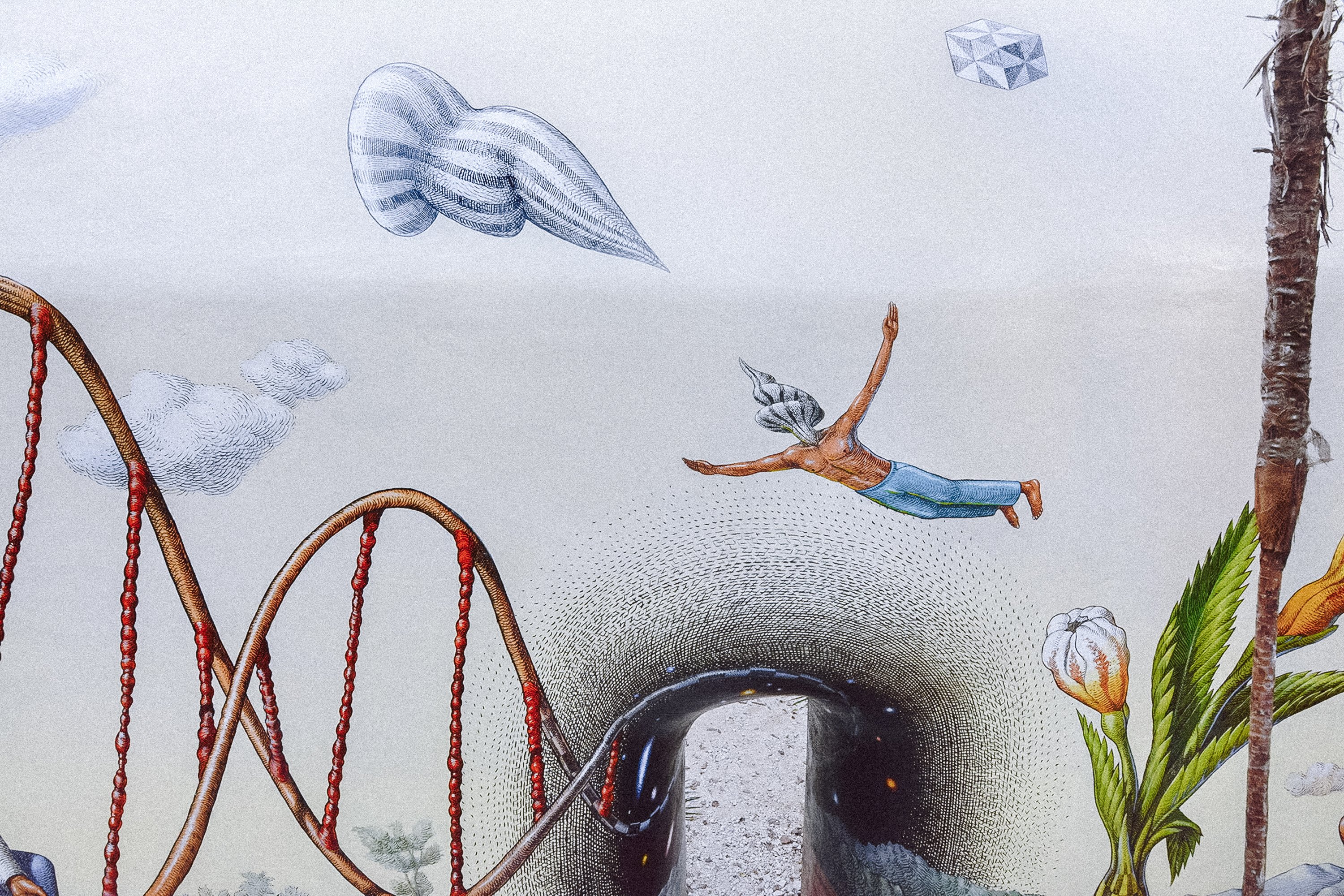

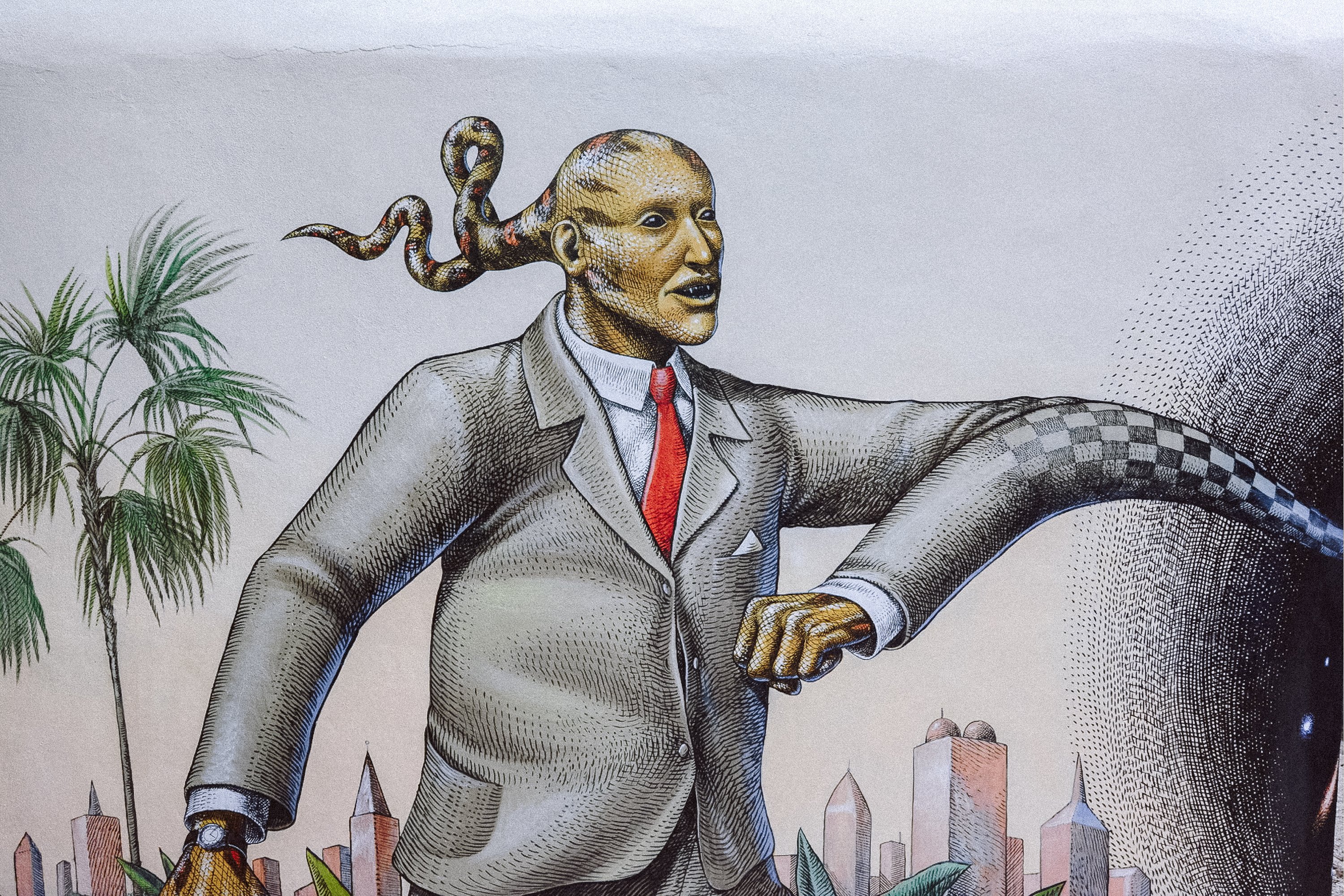

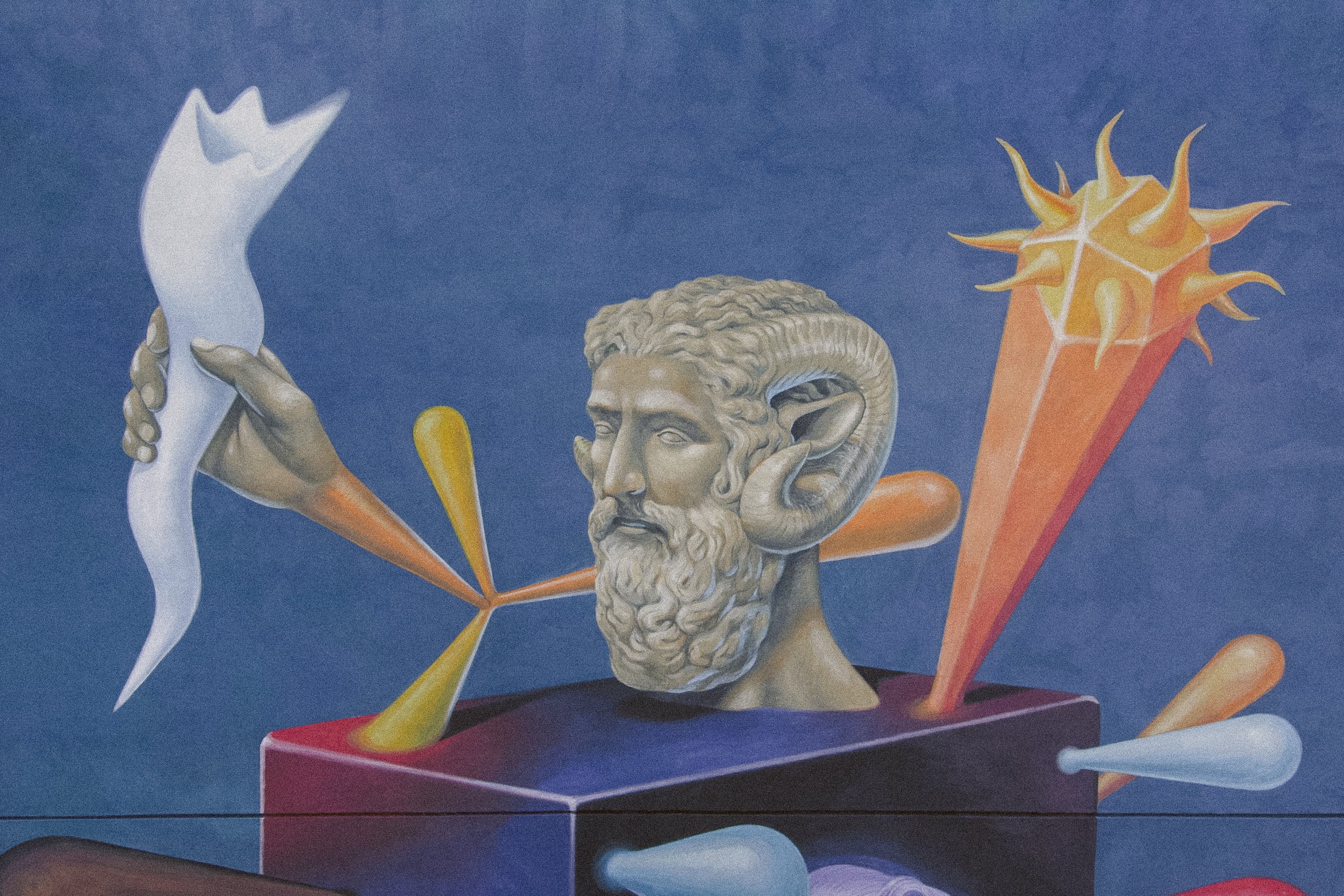

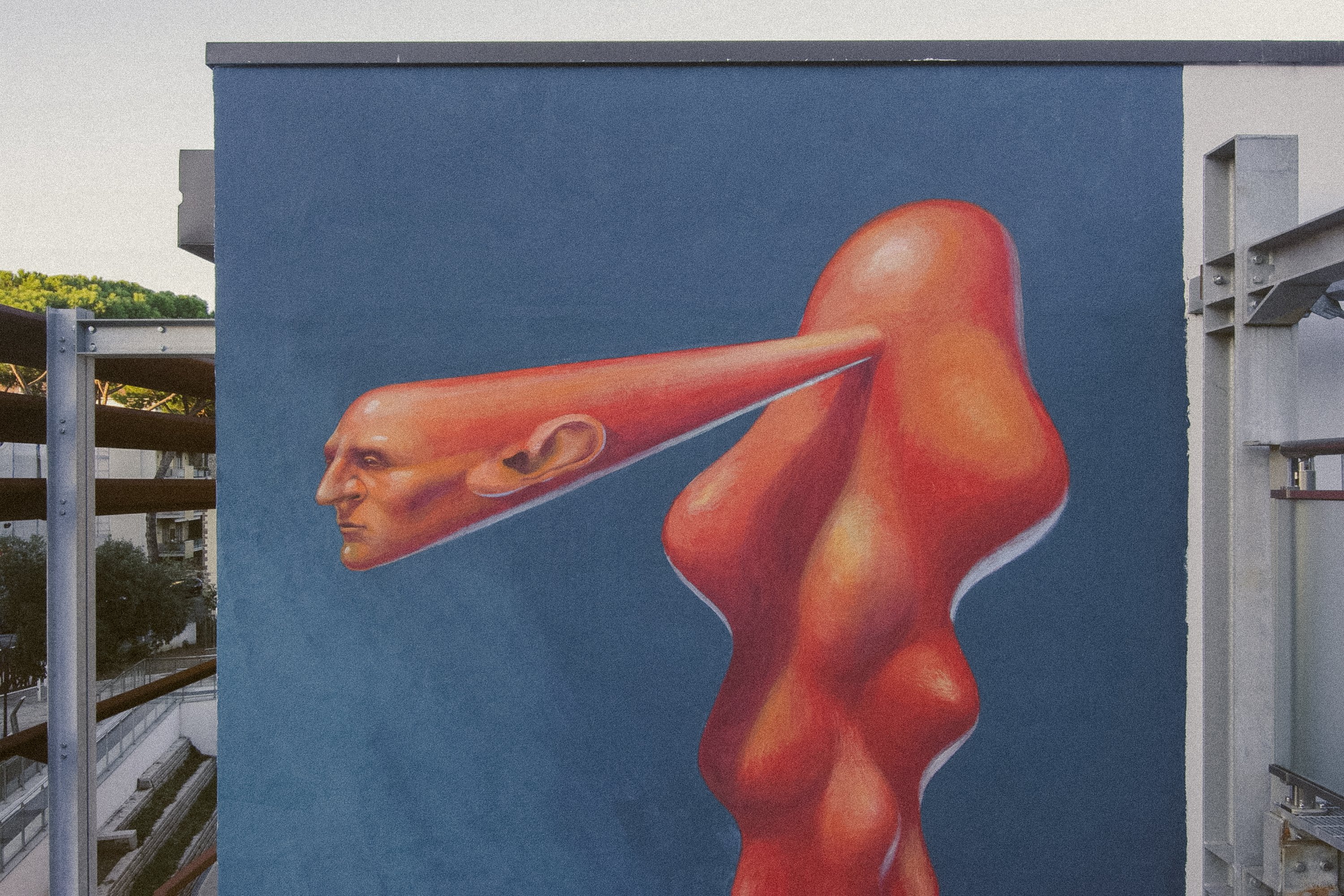

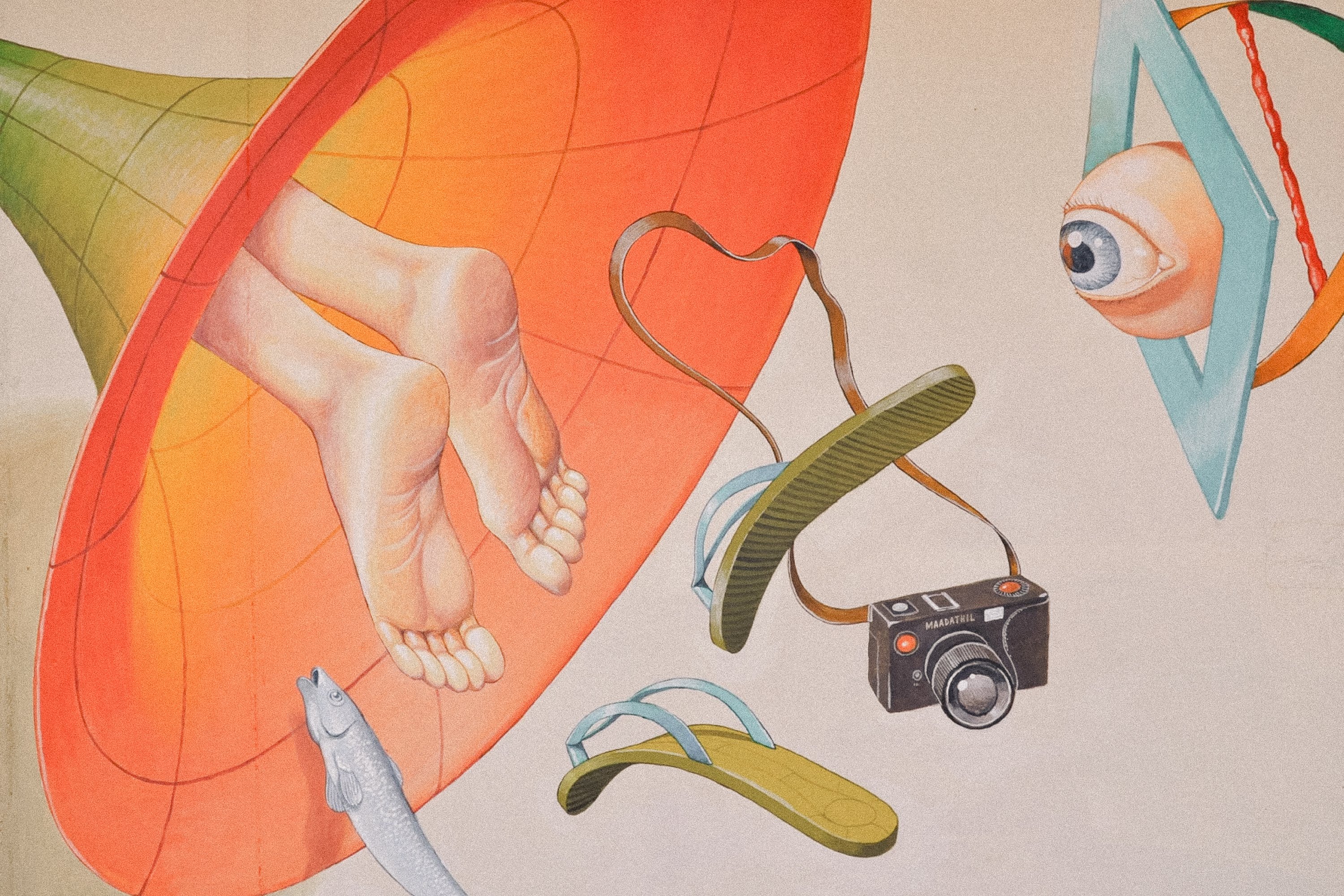

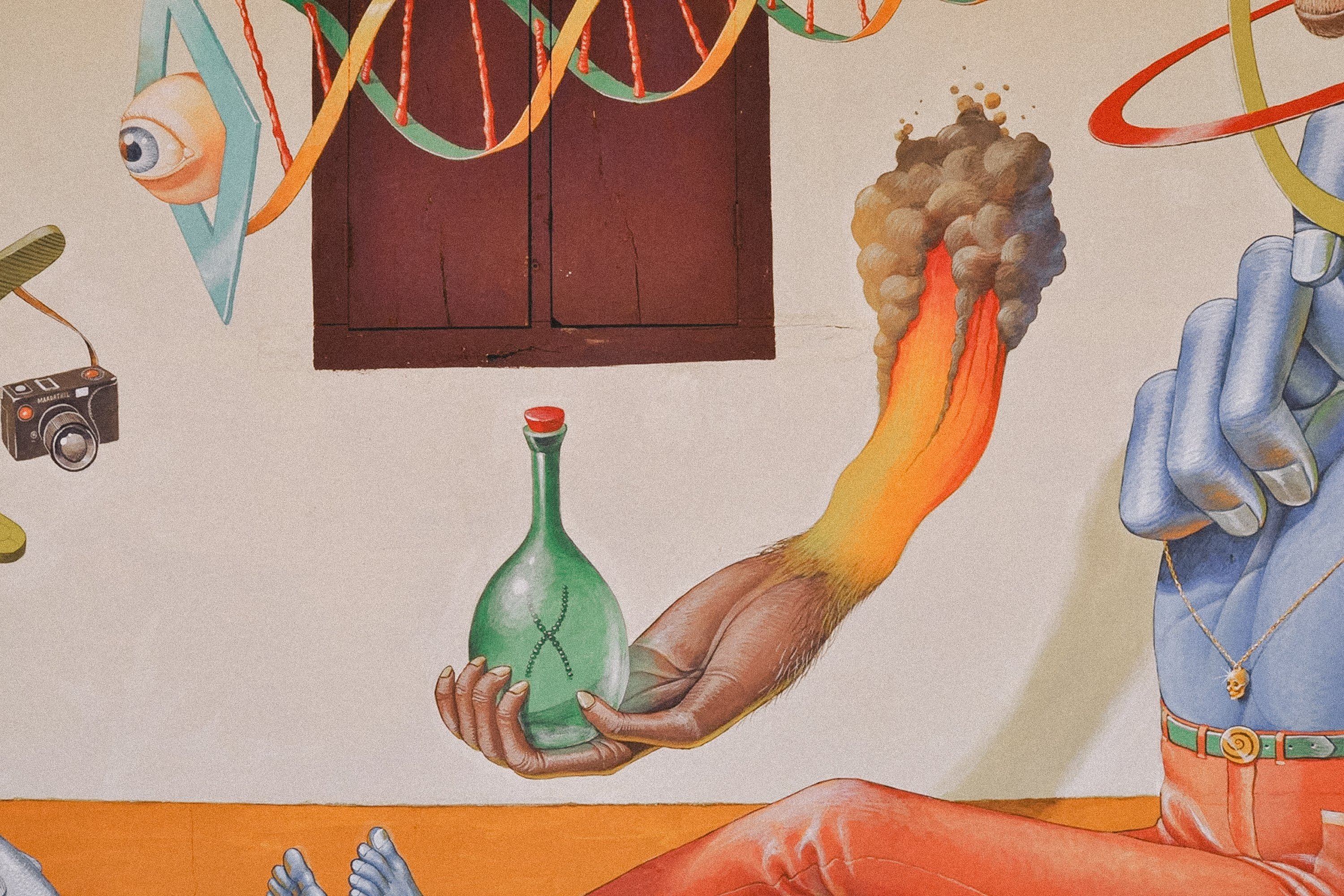

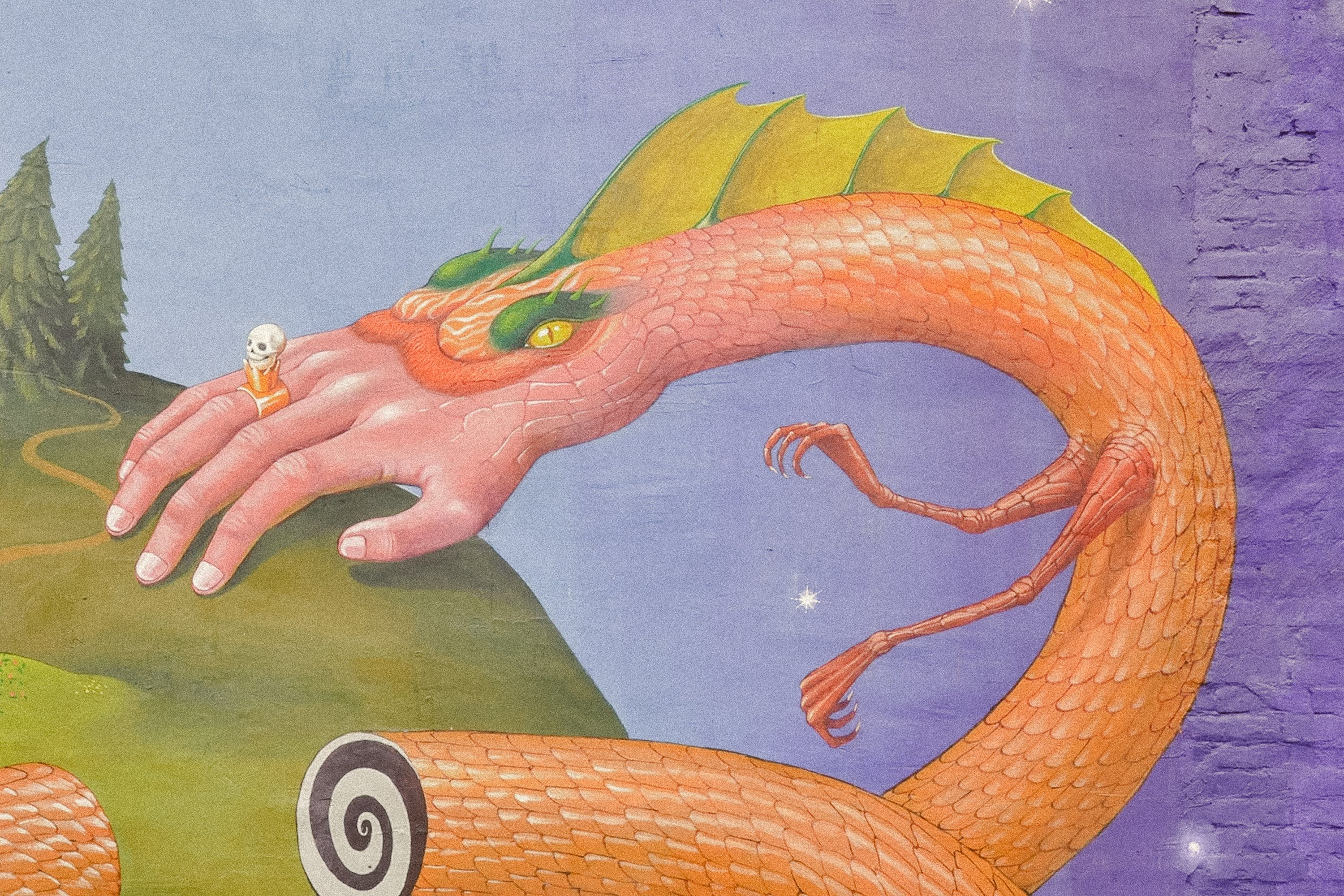

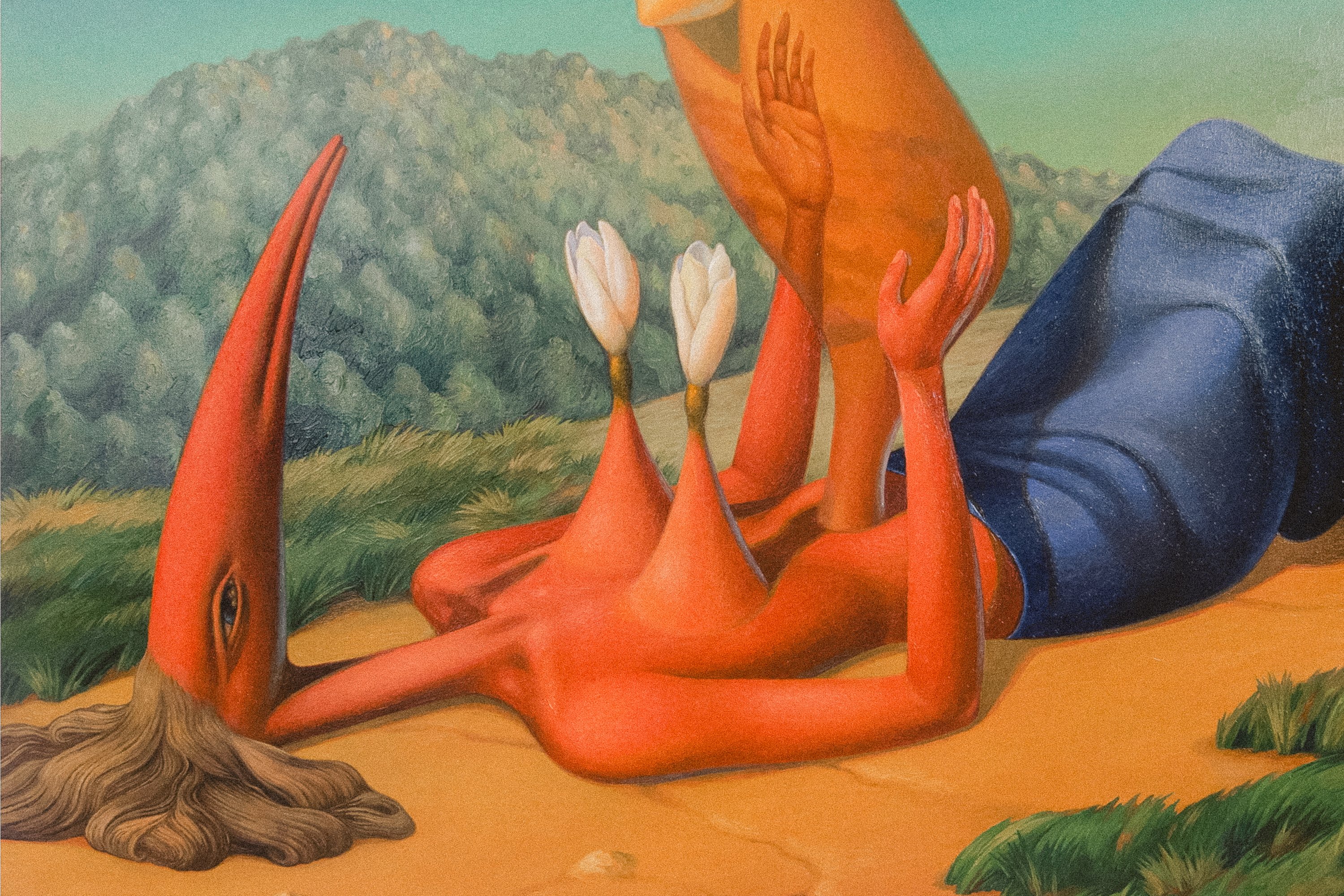

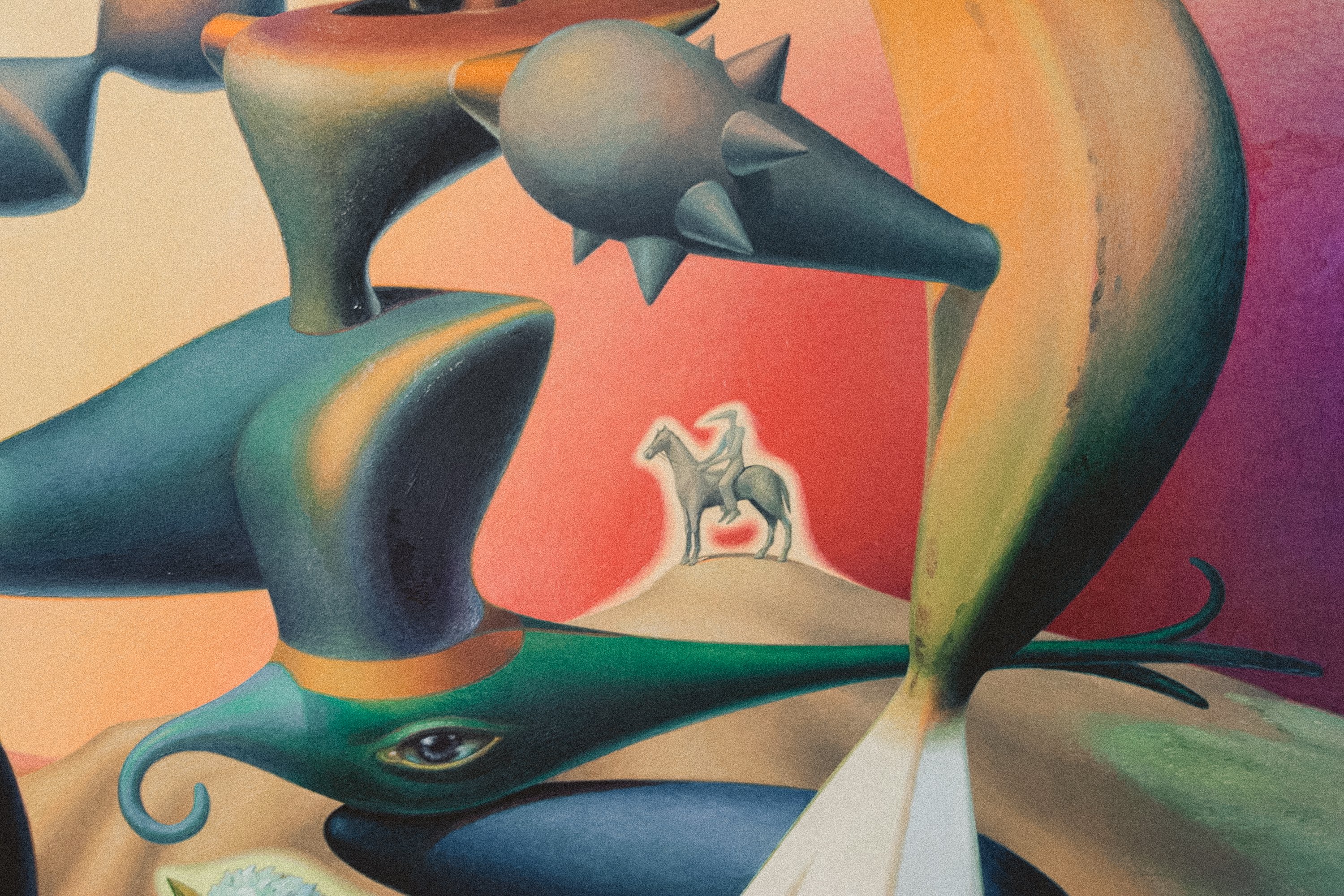

Bordusov’s artistic style has evolved over the years, from symbolic stylization to hyper-realistic detail. His works are about space, religion, mythology, and bold scientific theories, everything that helps explore and understand the universe. Aec chooses his materials carefully: acrylics for murals; in the studio, he uses watercolours, ink, and oil paints. But always with a brush, which is uncommon in street art. His visual language echoes the work of artistic legends like Hieronymus Bosch, Francisco Goya, Salvador Dalí, Diego Rivera, Moebius.

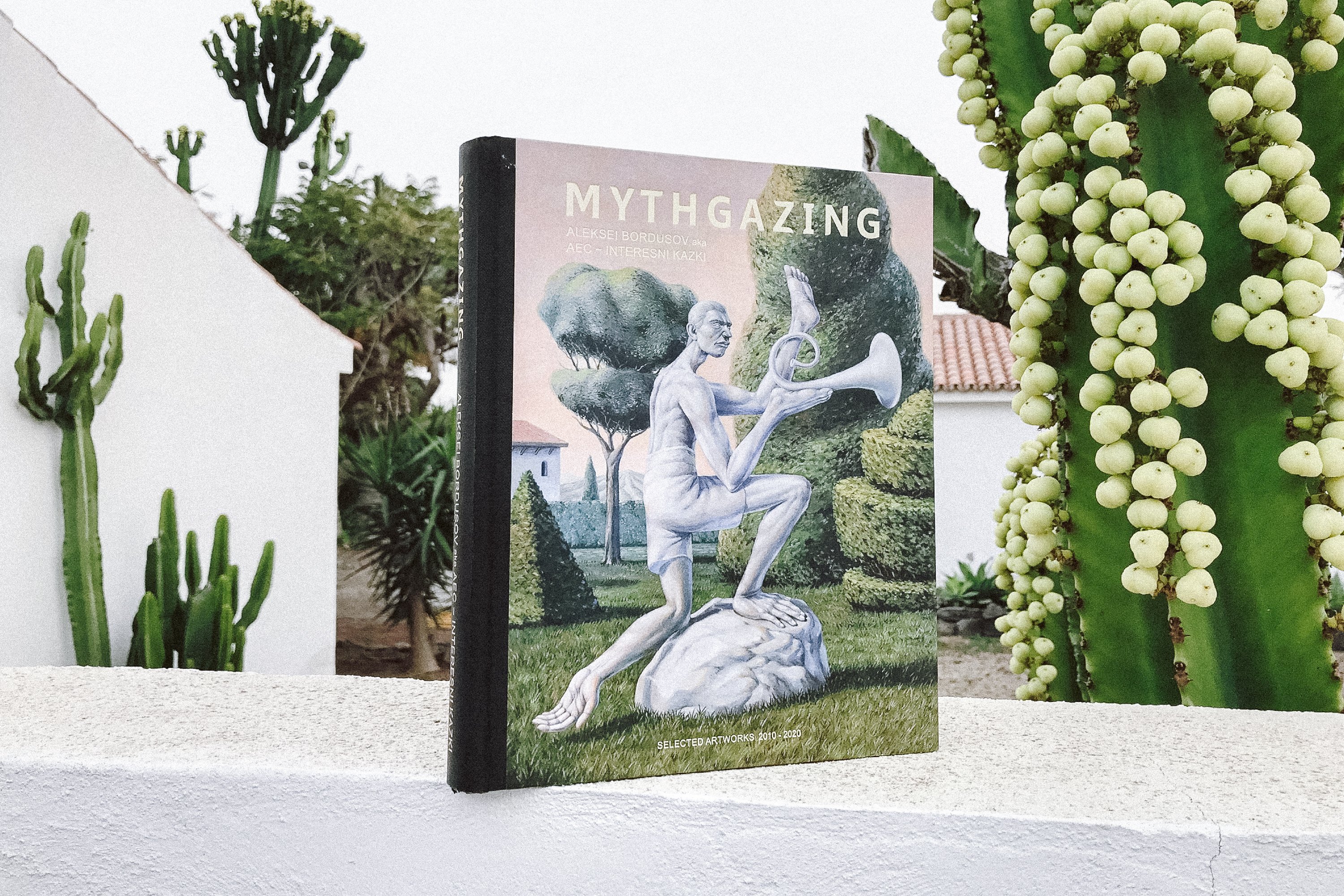

In 2021, Bordusov released Mythgazing — a monograph that gathers some of his most defining works from the past decade. Today, his murals are found across five continents, from France to India, from Brazil and the U.S. to South Korea.

When Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, Aec found himself on the island of Tenerife in Spain’s Canary Islands, where he was preparing for an exhibition. By April, he debuted Victoria, a solo show at Vienna’s Ag18 Gallery, dedicating it to Ukraine’s resistance in the face of Russian aggression. Today, Bordusov continues to live and work on Tenerife, focusing on bronze sculpture and painting. His artworks have now reached up to $40,000.

On how it started

I was 10 when my mom first took me to art school. She figured I was pretty good at drawing and that it was worth nurturing. But the place was nothing like what I’d imagined. I expected easels, brushes, and artists in berets… Instead, the teacher walks in and says, “Use your fingers. Dip your hands in paint and go for it.” It wasn’t that I was afraid of getting my hands dirty — it’s just that my expectations didn’t match the reality. I went home and told my mom, “I’m not going back there. That’s nonsense.”

In 1999, I started getting into graffiti and tried tagging my nickname, Alex, on fences. I was inspired by American and Brazilian graffiti and international magazines on the subject. That’s when I met roller skater Mark Pustovit, who founded the Kyiv graffiti club. That’s when I met Mark Pustovit, a rollerblader who had just founded the Kyiv Graffiti Club. The eight of us teamed up and formed a graffiti crew called Ingenious Kids. We painted trains, fences, buildings, always under the cover of the night, and we ran from the police. We competed with other graffiti crews, each trying to outdo the others with more stylish tags and bolder pieces. You’d sketch it out at home on paper first. Then it was out to the streets with your spray cans. And the rule was simple: paint fast, run faster.

On the rise of the Interesni Kazki art duo

In 2005, Manzhos and I became close and decided to step away from the crowd and start our own path. I think the secret to our success was our ability to blend our styles without clashing. We painted freestyle without discussing the details, it just came naturally together. That natural flow was the foundation of our collaboration. We tried combining our vision of science fiction, mythology, philosophy, and both Ukrainian and global culture in our murals.

For a long time, we were commissioned to paint computer clubs. We’d wrap them up in under two days, and each earned $100. People found us through word of mouth. These commissions were more of an opportunity — a way to earn some money and have leftover paint to create our own work. We often went painting along the Lybid, a river in Kyiv lined with endless concrete walls. Illegal, of course, but the cops almost never showed up there. It was the perfect spot for street art.

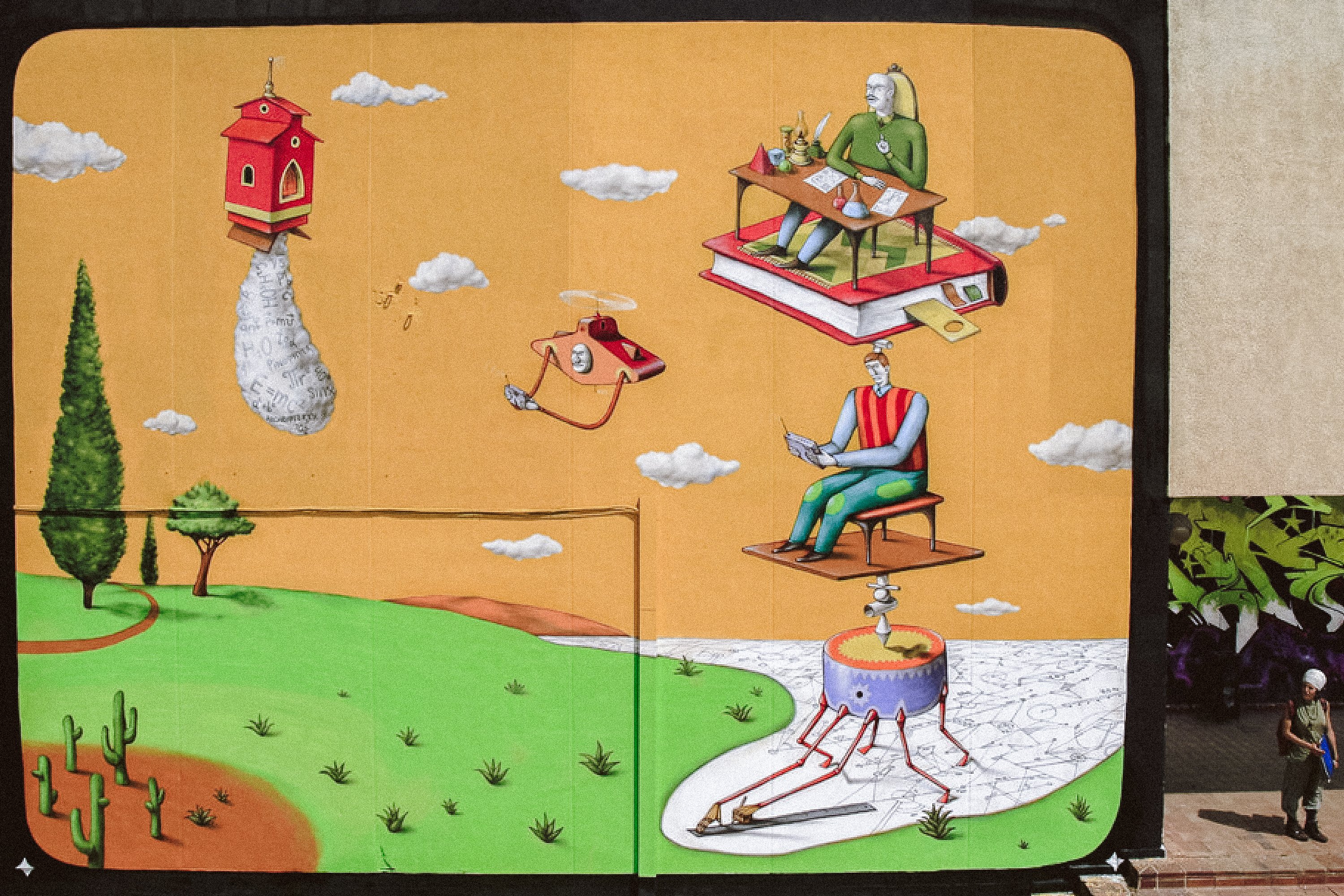

On Interesni Kazki’s international debut

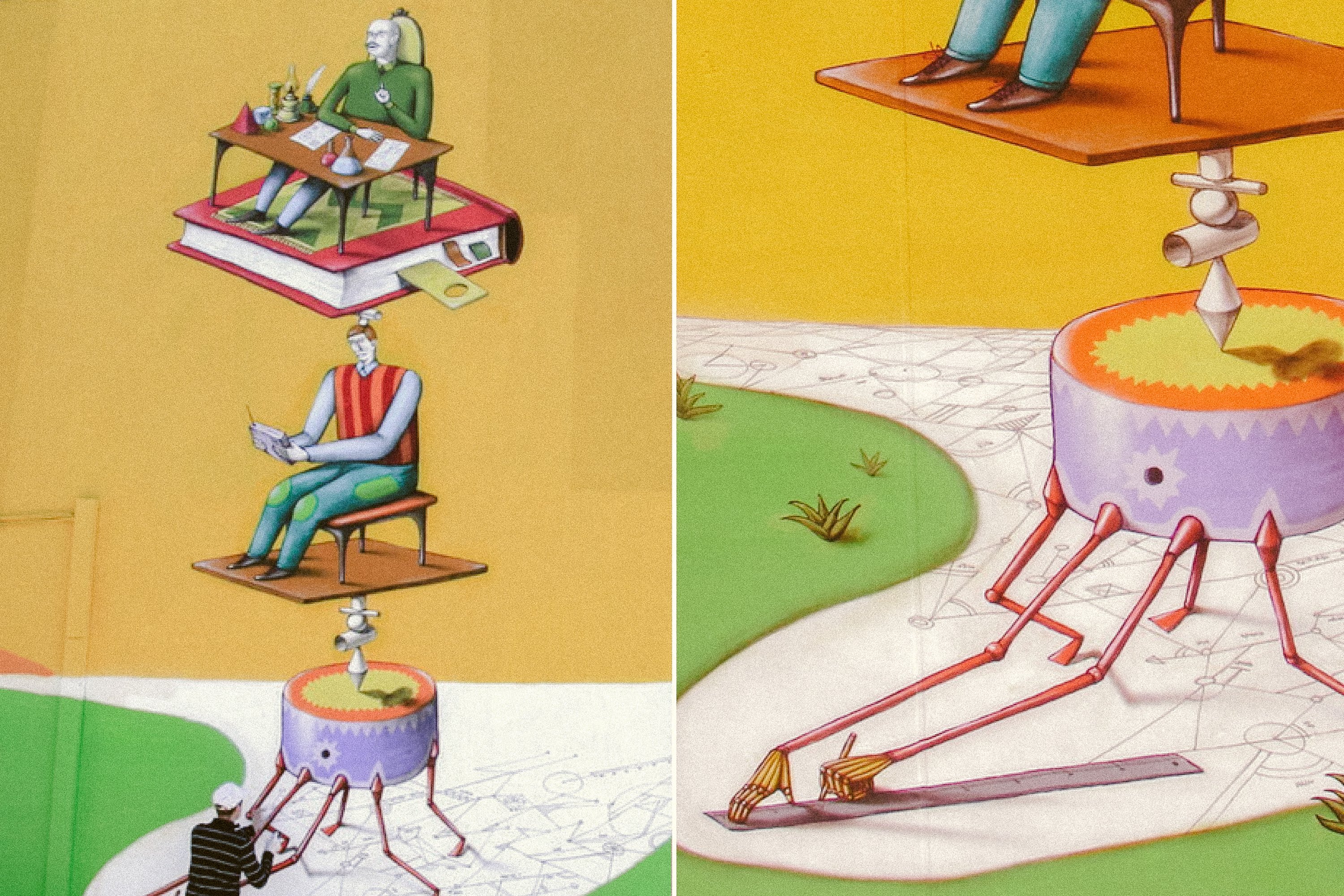

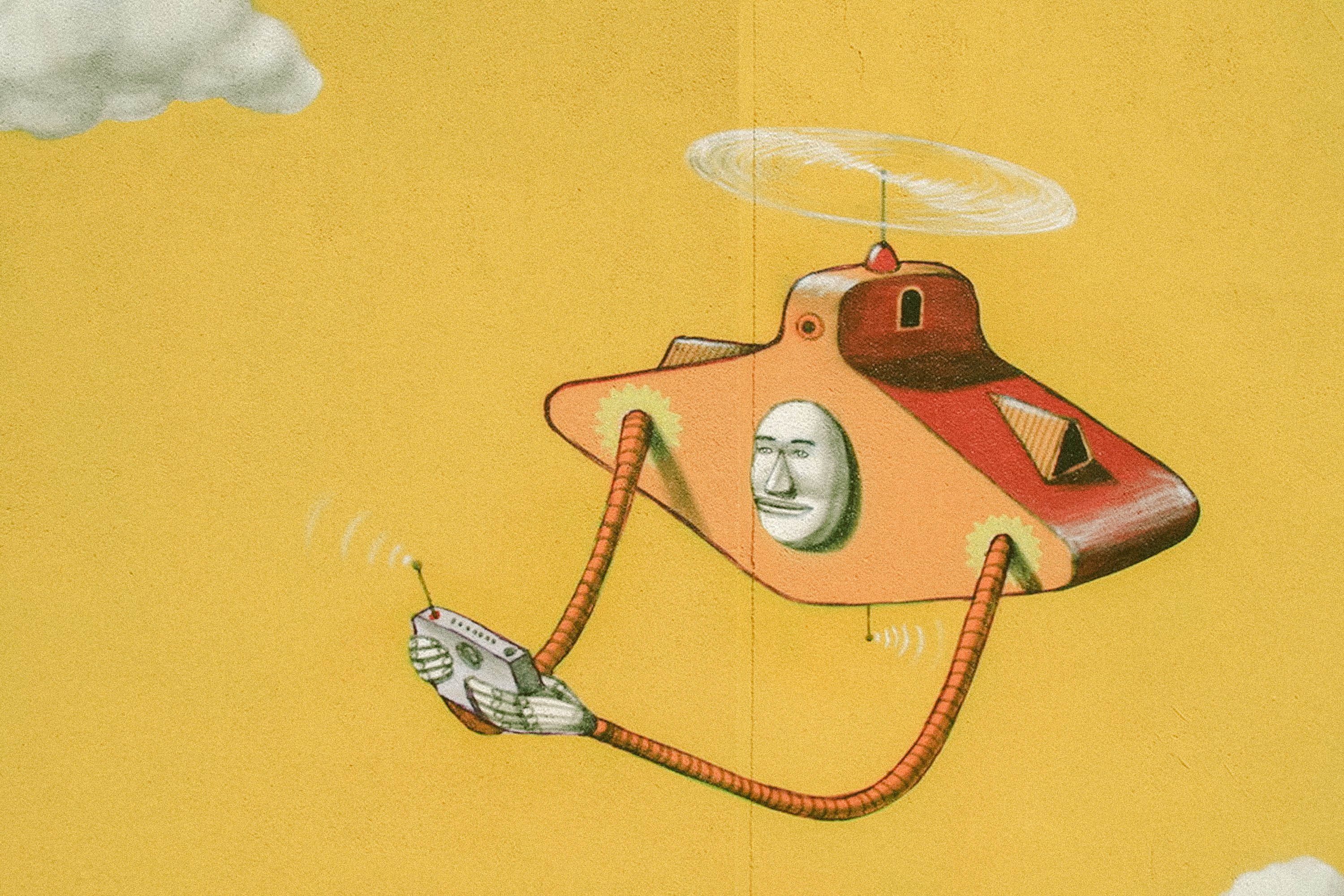

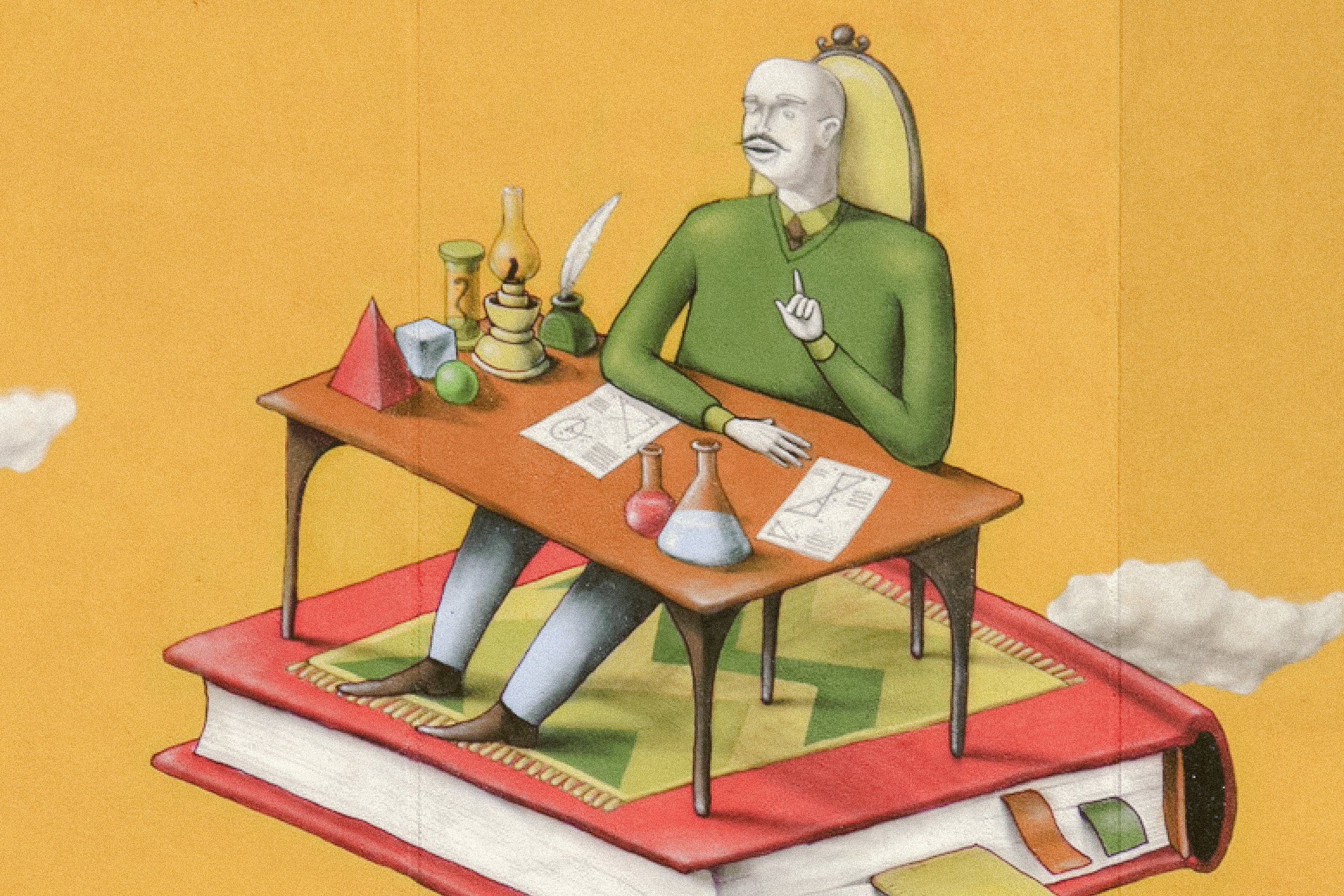

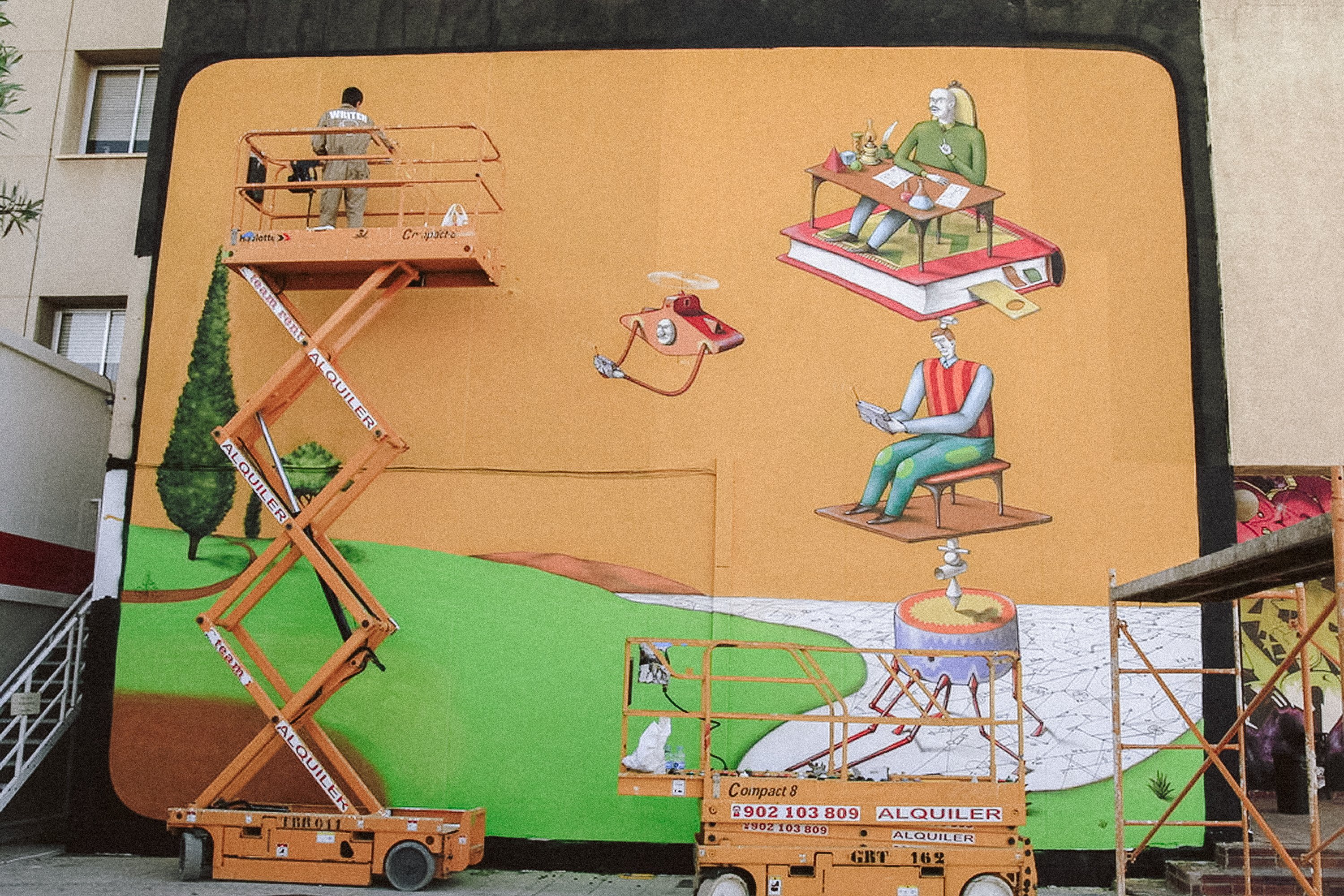

Our first project abroad was a street art festival in Valencia in 2009. They covered our travel and accommodation costs, but there was no artist fee. In return, we were given complete creative freedom, with just a loose theme: “Create something that fits the vibe of the Polytechnic University,” since that’s the wall we were painting. I came up with a robot drafting blueprints, and Volodymyr added a scientist character. After that, we started getting invited to all the major street art festivals around the world.

At the same time, we continued working a lot in Ukraine. We did interior design projects, including in the “Bilsovyk” shopping centre — now known as “Kosmopolit.” We began working there in 2007 and continued until 2011, creating a total of eight pieces. Each one was paid $4,000.

In the winter of 2010, we had our first solo show as Interesni Kazki in Lyon, at a small gallery called ALL OVER. We lived there for two months — painting, prepping, building the exhibition. Three of our pieces sold.

On the influence of Latin American culture

Diving deep into Mexican culture during the All City Canvas festival in Mexico City had a powerful impact on me. The country’s mural tradition is rich in political themes. I was impressed by the works of Siqueiros, Orozco, and Rivera. What also moved me was the incredible depth of Mexico’s past, its folklore, the Aztec and Mayan cultures. It wasn’t just about the well-known cult of death, it was a whole universe of mythology and symbolism. That’s when something important happened: I began painting walls with brushes. I wanted to achieve the highest level of detail possible.

On breaking into the U.S. art scene

I remember our first trip to the U.S. in 2011 really well. We were stopped at passport control as the officers weren’t sure whether to let us in: we were too young, didn’t have a formal contract, and they kept asking, “What exactly are you planning to do here?” They warned us we might be scammed and even advised us to turn back. There we were, in the USA, standing right at the border. One of the officers asked, “Why were you invited? How do people know who you are?” And I just said, “Well… we’re famous.” He grinned and replied, “Oh, well, if you’re famous — go on then.”

That’s how we ended up at the Wynwood Walls Project by Tony Goldman, an open-air gallery where old warehouse walls were turned into canvases for some of the world’s most famous street artists. We returned to Wynwood two years later. And since then, we’ve painted across the U.S. more than a dozen times.

On the most challenging, most expensive, and meaningful works

The mural Icarus, which I painted in Mexico City in 2017, was definitely one of my most intense experiences. The building was massive, at least fifteen storeys high, and I had to paint from a swaying suspended cradle that swayed constantly. At one point, it suddenly dropped and slammed into the wall. Thankfully, I was on a lower level, so I wasn’t injured. But I spent several more days finishing the mural under constant stress. What made it even more surreal was the subject: Icarus was free-falling, wings on fire, like a symbolic businessman crashing and burning, losing everything. I was fascinated then by the theme of collapse, of falling from the top.

The most expensive piece I’ve created was in 2024: a canvas for the U.S. company Mailchimp Intuit, which develops software for large businesses. I painted Mysterious Event in the Valley for their new office in Atlanta. I created it here in Spain, rolled it up, packed it, and sent it across the Atlantic. The project cost them $40,000.

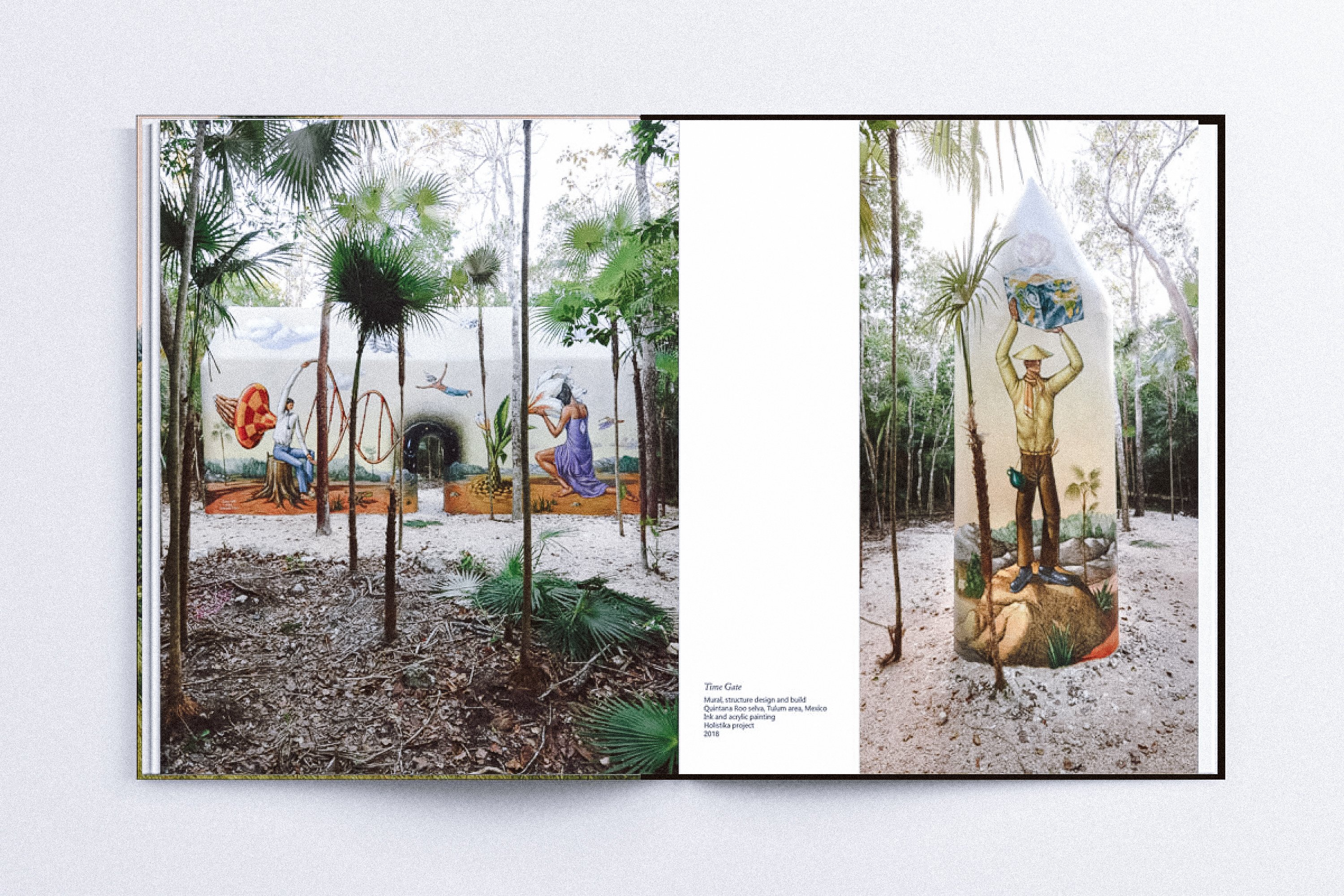

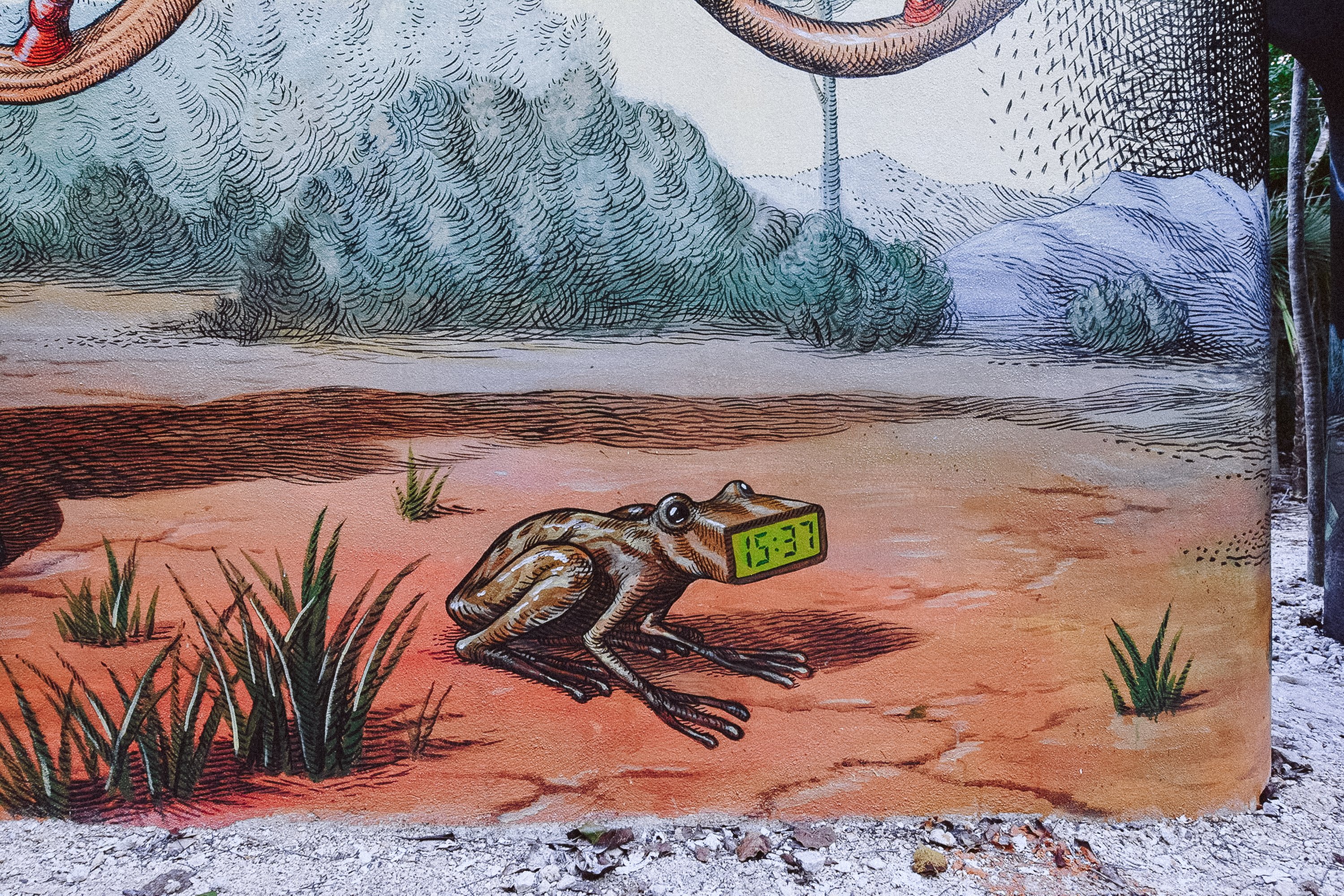

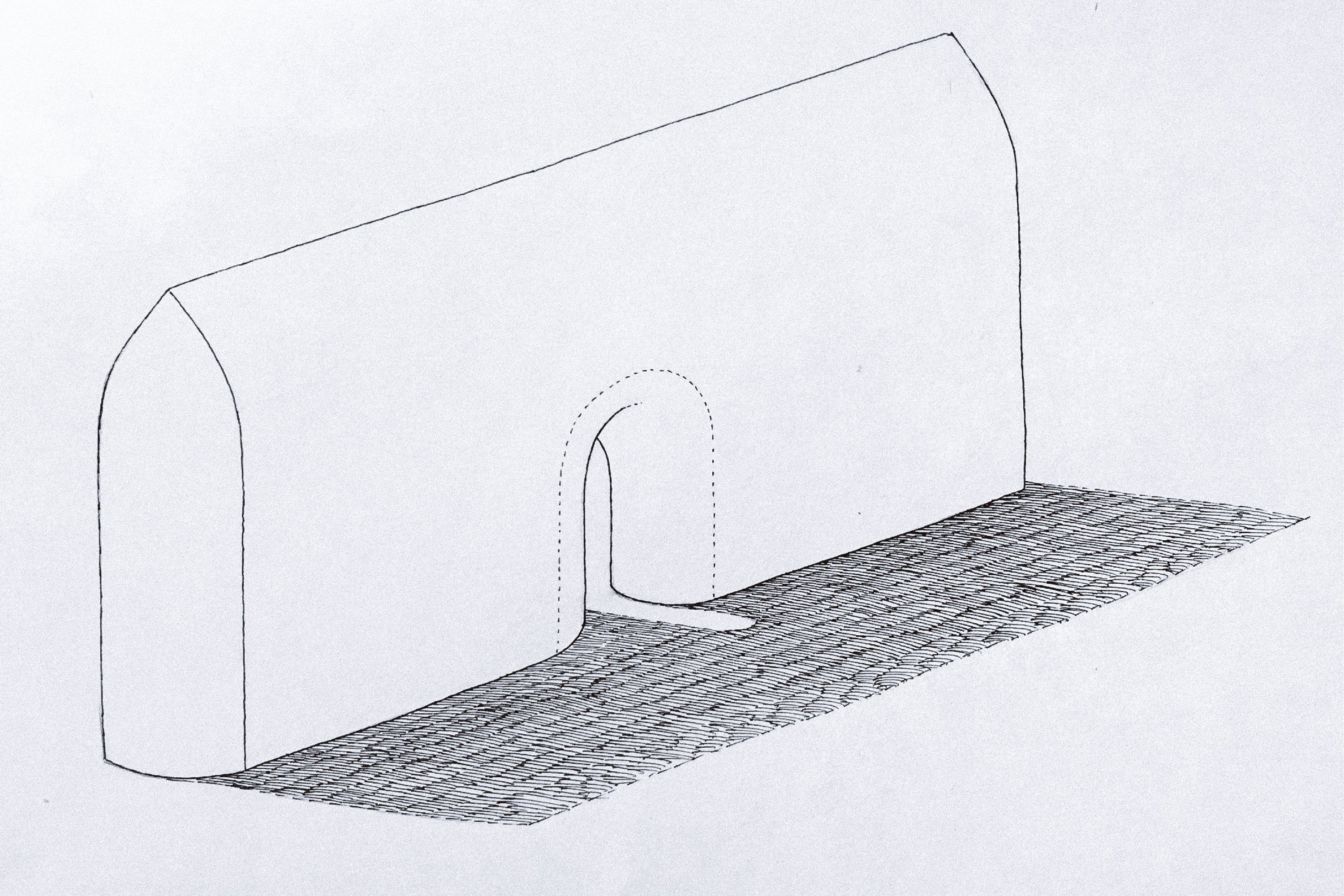

It always feels like you’re chasing perfection, and with each new piece, you think it’s your best yet. But one of my all-time favourites is Time Gate, a project I did for a resort complex in the jungles of Quintana Roo. I was given full creative control — even the wall it was painted on was my design. I developed its structure, shape, and technical drawings before handing them off to the builders. The resort’s guests walk along a jungle path and come upon the mural surrounded by nature. The idea behind it was a portal through time. While working on it, I became suddenly aware of how differently time flows in the jungle compared to a hectic city. You could really feel a strong presence of Mayan culture. The locals still hold a completely different sense of time than the tourists.

On well-known figures in murals

A school in Florence invited me to create a mural about Margherita Hack, the Italian scientist who popularized astronomy. At first, I hesitated. I thought maybe it wasn’t the best fit, I don’t usually work with portraits of specific people. But once I started researching who she was and what she did, several ideas came to mind. Another important point was that there was no expectation of a traditional portrait. I merged her image with that of Amun-Ra, the ancient Egyptian Sun god. I found it interesting that, at a certain point in history, Egyptian and ancient cultures partly overlapped. Amun-Ra, as the god of the heavens and stars, felt like a perfect symbolic counterpart to Hack’s work in science and astronomy. The school approved my concept and sketch and invited me to bring it to life. I spent about two weeks painting the mural. The commission was €6,000.

On where ideas come from

All of my visuals come from the subconscious. I’ve tried to figure out for myself where from, but it’s impossible. Sometimes they appear in dreams, other times while I’m out walking or biking: a sudden spark — “Why didn’t I think of this before?” I head home and put it down in a rough sketch to capture it.

On people’s reactions to the process

Most of the time, people are curious, but there are exceptions. I remember painting in Moscow about 12 years ago, when a woman approached me and asked, “Why are you painting some Kazakh pattern in the middle of Moscow?” It was pure chauvinism. Once in Houston, a man approached visibly agitated and snapped, “You need therapy.”

It’s not unusual for people passing by to joke, “What are you on, what’s going through your head?” But in India, it was a whole different experience. People gathered around and watched for hours as I worked. They brought food and drinks, offered encouragement, and showed genuine appreciation.

On politics in Bordusov’s art

After 2014, I completely cut off all collaboration with Russians. I ended every project, even though the invitations kept coming. The last time I painted in Moscow was in 2013, a year before Crimea was annexed. Even then, you could sense something was shifting. As soon as Ukraine came up in conversation, the tone would change, imperialist remarks would come out, and it deeply upset me.

In 2014, during the invasion, I painted the mural in Kyiv called Saint George. It was full of Ukrainian symbolism — a falcon, a Cossack slaying a serpent. I wanted to create a strong image of protection and resilience.

But afterward, I decided to step away from direct and literal imagery. It started to feel too opportunistic. No one asked me to change course, it was entirely my choice. I funded the entire project myself: paint, lift equipment, wall prep. In total, I spent about €5,000. But at the time, it just felt like something I had to do.

On creative shifts during the pandemic

In 2019, I transitioned from using acrylics to oil paints. The technique reshaped not just how I painted, but what I painted: the imagery, the form, the rhythm of creation itself. Then the pandemic hit, and it created the perfect conditions for focusing on studio work. I didn’t paint murals then. I simply stayed put in my apartment-studio in Kyiv’s Vynohradar district, quietly working on canvases. It was a period of intimate, quiet creation — a time when I could fully immerse myself in the process, with no noise of the outside world.

On emigration

Emigration wasn’t something I had planned. My wife and I left for Spain about a month before Russia’s full-scale invasion. I was preparing for a solo exhibition in Vienna, and people we knew invited us to stay in Tenerife. I intended to create a few new works here, and then the war began. We decided not to return: we no longer had our own home in Ukraine. I had been to Tenerife once before. In 2021, I came for an artist residency, and knew I wanted to return. It turned out to be the perfect place to focus.

Emigration changed me, although I’m still trying to understand how deeply and in what ways those changes are shaping my art. The place I now live is completely different from Kyiv: the climate, nature, culture, mentality, and pace of life. And of course, the language which is difficult for me, and without it, integration is difficult.

Routine is essential. It brings structure and discipline. I work in the studio even when I don’t feel inspired, because it often comes in the process. It’s like an engine that won’t start at first, and then slowly kicks into gear. Sometimes, looking at other artists’ work helps spark ideas. Sometimes it’s books. Sometimes it’s a walk in the mountains. I don’t keep a fixed schedule, but I work 8 to 9 hours a day, just not always at the same time. I follow the rhythm of the day as it comes.

On the Victoria exhibition in Vienna

I created most of the paintings for Victoria before the war began. Only one was made in Vienna and directly connected to the full-scale invasion. Somnia Belli — I painted it right in the gallery, just before the opening. That said, themes like conflict, fear, the search for meaning, and the nature of good and evil have always been present in my work. It was important for me to focus not on the events themselves, but on the feelings they evoke. People with bodies like trees, beings with mask-like faces, trees with ears, disconnected buildings — this world is both fantastical and unsettling. It doesn’t ask for logic — it asks for intuition, feelings.

As art historian Kia Waland wrote: “Art can’t stop war, but it can give us a pause, a chance to look deeper, and to find hope.” That, to me, is what Victoria is really about.

The gallery partnership worked like it always does: a 50/50 split. They represent me, cover the space rental, and handle all the preparation — stretching the canvases, building the frames. Then they promote the works to their collectors. In my opinion, it’s only fair that galleries take half — they earn it.

On sculpture

I started working in sculpture in 2024, and it’s completely pulled me in. For a long time, I wasn’t sure I was ready. I didn’t want to simply repeat in sculpture what I was already doing in painting, I didn’t want to duplicate my visual language in three dimensions. Subconsciously, I suppose the ideas had been building for a while, and late last summer, I simply bought a block of clay and decided to experiment. I immediately felt drawn in — I found an approach that felt natural to me.

I’m not interested in academic realism or perfect anatomical form. For me, sculpture isn’t about storytelling, as painting often is, it’s about the process of shaping. And interestingly, ever since I started working in volume, my painting has also changed: I now pay much more attention to form, not just to meaning. I see that as a very positive development.

Here in Tenerife, where I currently live, there’s a remarkable foundry called Esculturas Bronzo. I bring in models sculpted from clay or plasticine, and they create moulds and cast them in bronze. A single edition usually costs around €1,200, depending on size. To support this work, I’m currently seeking investors. For anyone interested in backing one of my sculptures, I offer a 50/50 profit-sharing arrangement.

On self-identity

I have no interest in exploiting the fact that I’m a Ukrainian artist just because the war has brought more international attention to Ukraine and its artists. What matters most to me is that my work is evaluated for its content and quality, not based on where I’m from. At the same time, I always say with pride: I’m from Ukraine.