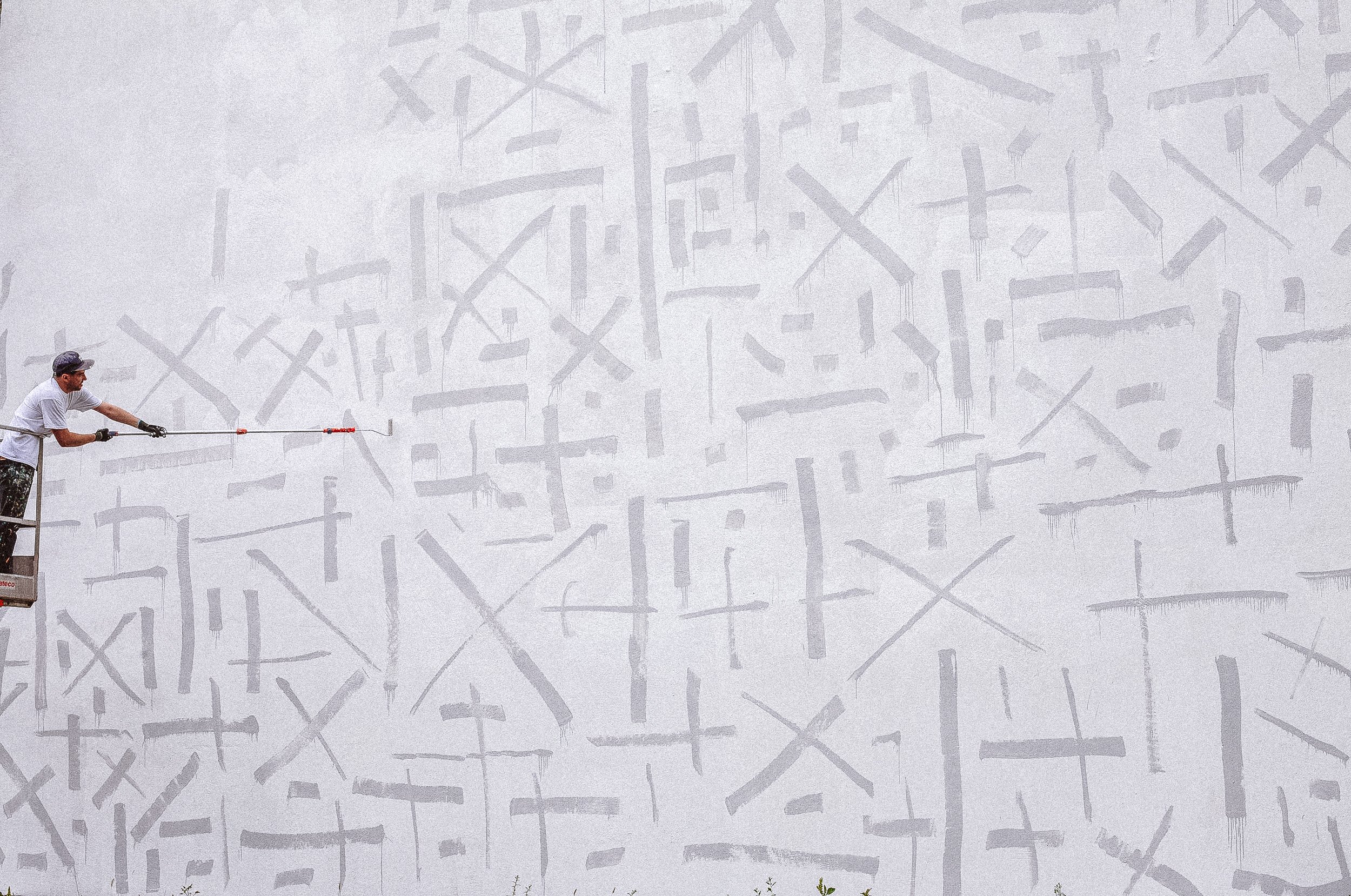

In the late ’90s, Volodymyr Manzhos spray-painted ‘Waone’ on the wall, the name that would become his artistic alias. Back then, it wasn’t about sending a message or making a statement, just raw instinct and the moment’s thrill. But that impulse never left him. He’s been painting walls ever since. In the early 2000s, together with artist Oleksii Bordusov (artistic alias AEC), Manzhos formed the art duo Interesni Kazki.

After they parted ways in 2016, Waone launched his solo journey. His projects have since become political, social, and cultural manifestos. Today, his artwork is sold at Christie’s, his clients include Hermès, Kyiv TSUM department store, and the Paris airport. The artist’s murals have become a hallmark of contemporary Ukrainian art on the global stage, from Valencia to Mexico City and São Paulo. His more than 120 murals have appeared at Miami’s Wynwood Walls and street art festivals in Rabat, Washington, Perth, Jacksonville, Detroit, and Lisbon.

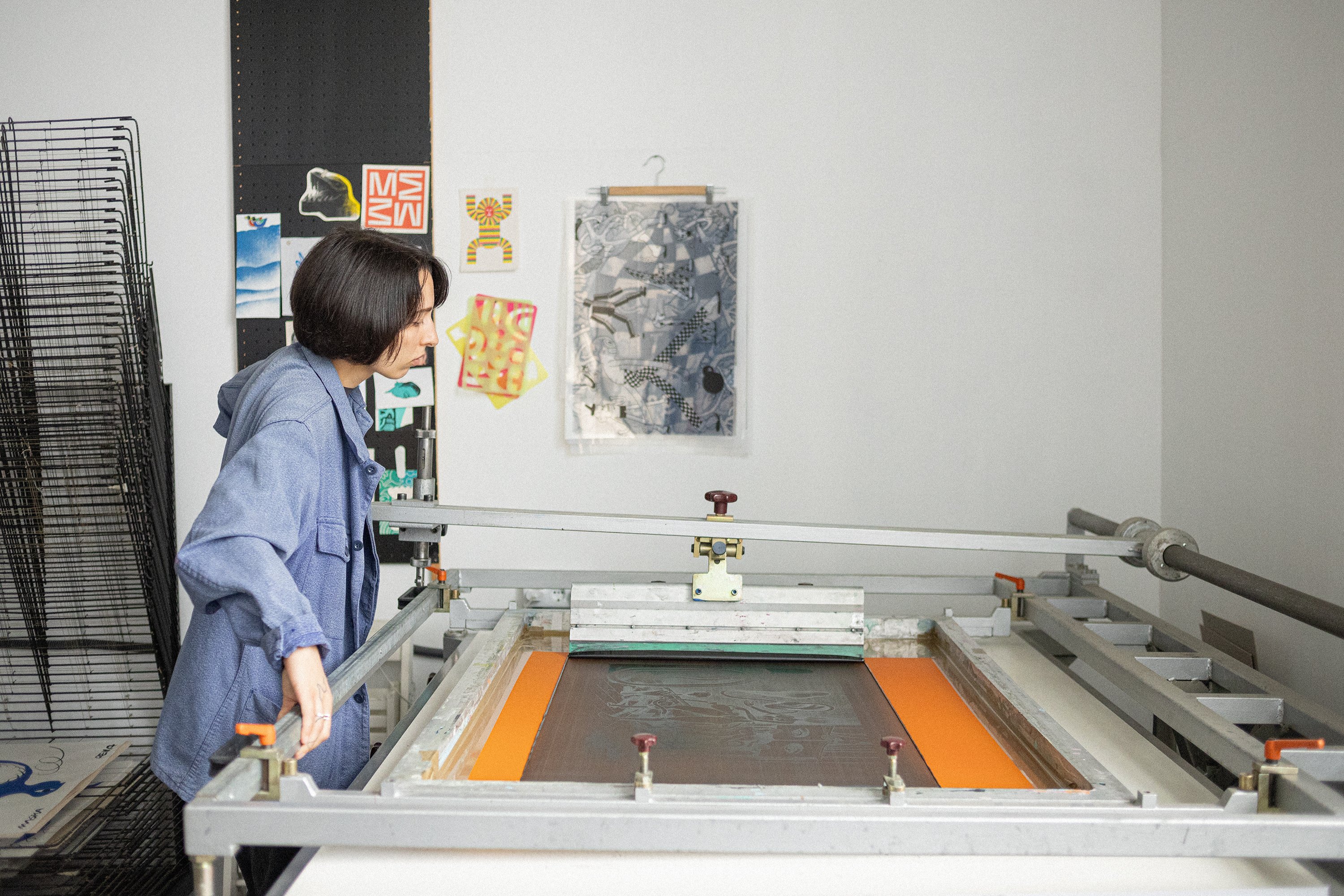

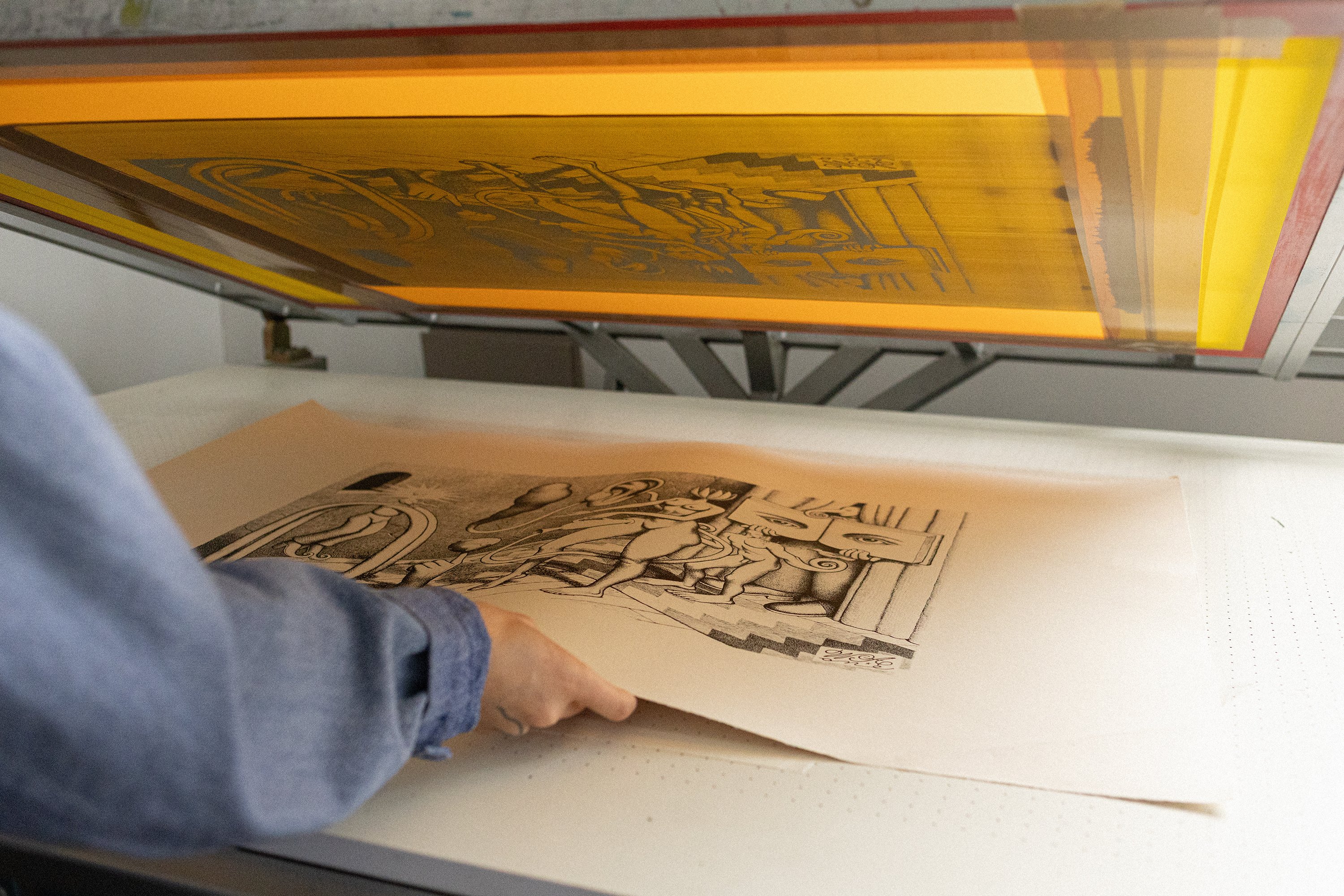

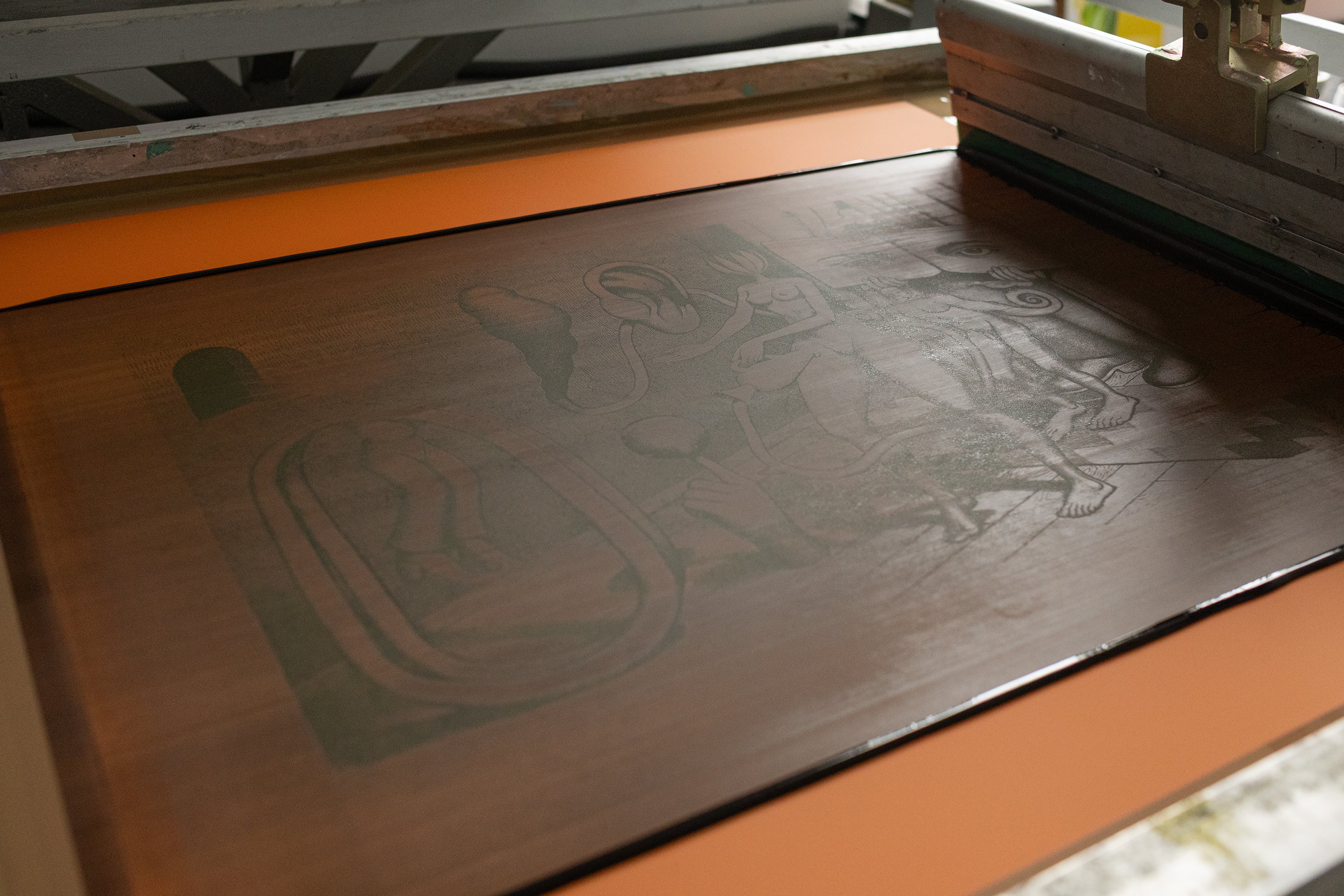

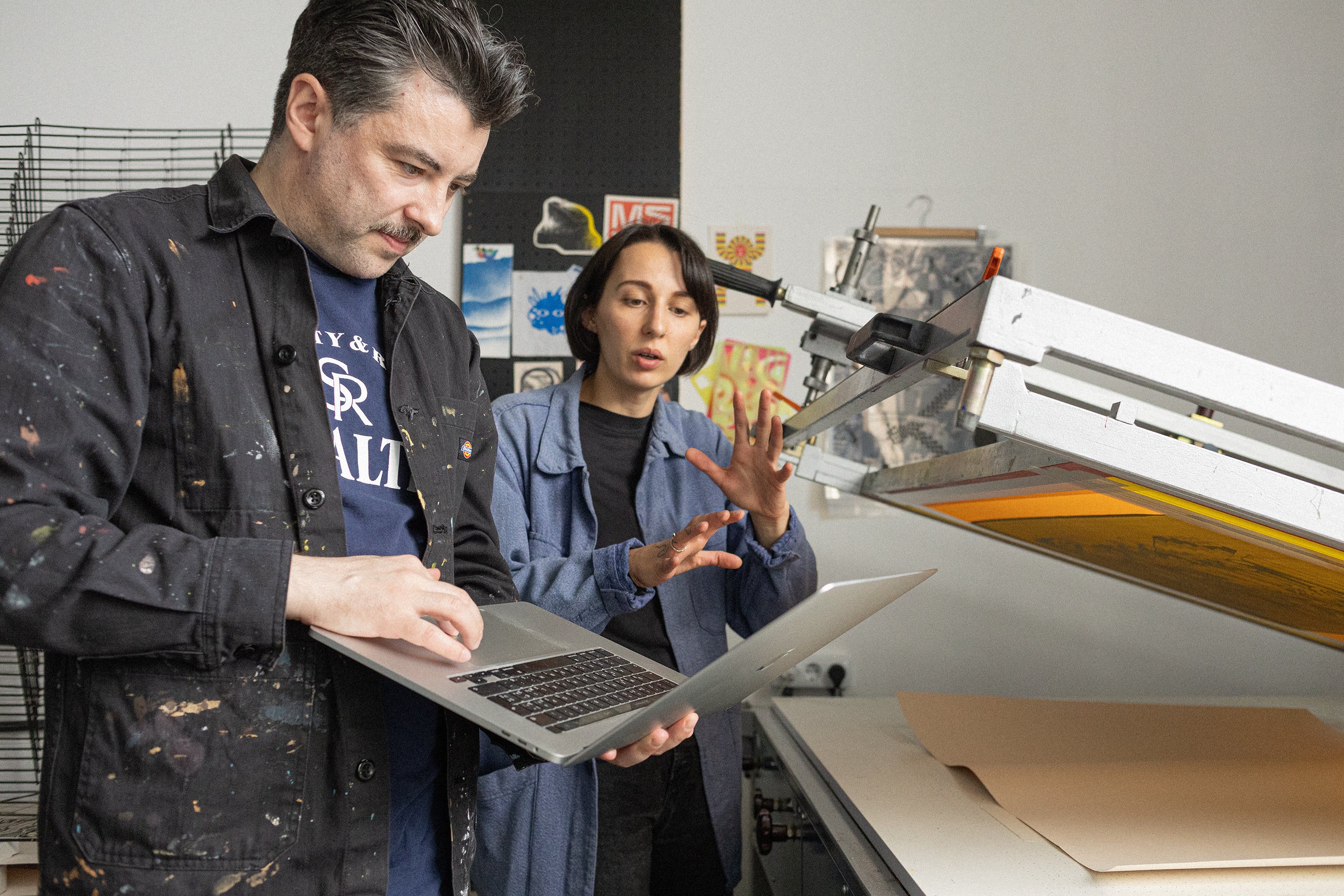

Though he now works in Ukraine, he also creates linocuts in Paris at renowned studios like Idem Paris and Arte — spaces once graced by legends like Picasso, Miró, and Giacometti.

In 1999, twenty-year-old Volodymyr Manzhos and his mother were taking his younger brother to a healer in the Kyiv region. At the time, visits like that weren’t uncommon. In the post-Soviet years, psychics and energy healers were highly popular. His brother had been ill since childhood, and the family was open to any form of help. The night before, Volodymyr had a strange dream: a doorbell rang in a dimly lit evening house. A dark silhouette appeared outside the window. He never opened the door, and for him, it carried symbolic meaning: not to make peace with evil, not to open the door to it. The next morning, the healer barely glanced at him and said to his mother, “He’s under the dome now.” At the time, Manzhos was still a student at an agricultural university, just starting to experiment with graffiti. When asked what he saw in his future, he hesitantly replied, “I think I want to be an artist.” The healer nodded, telling him that a true artist must treat creativity as a gift and be open to it.

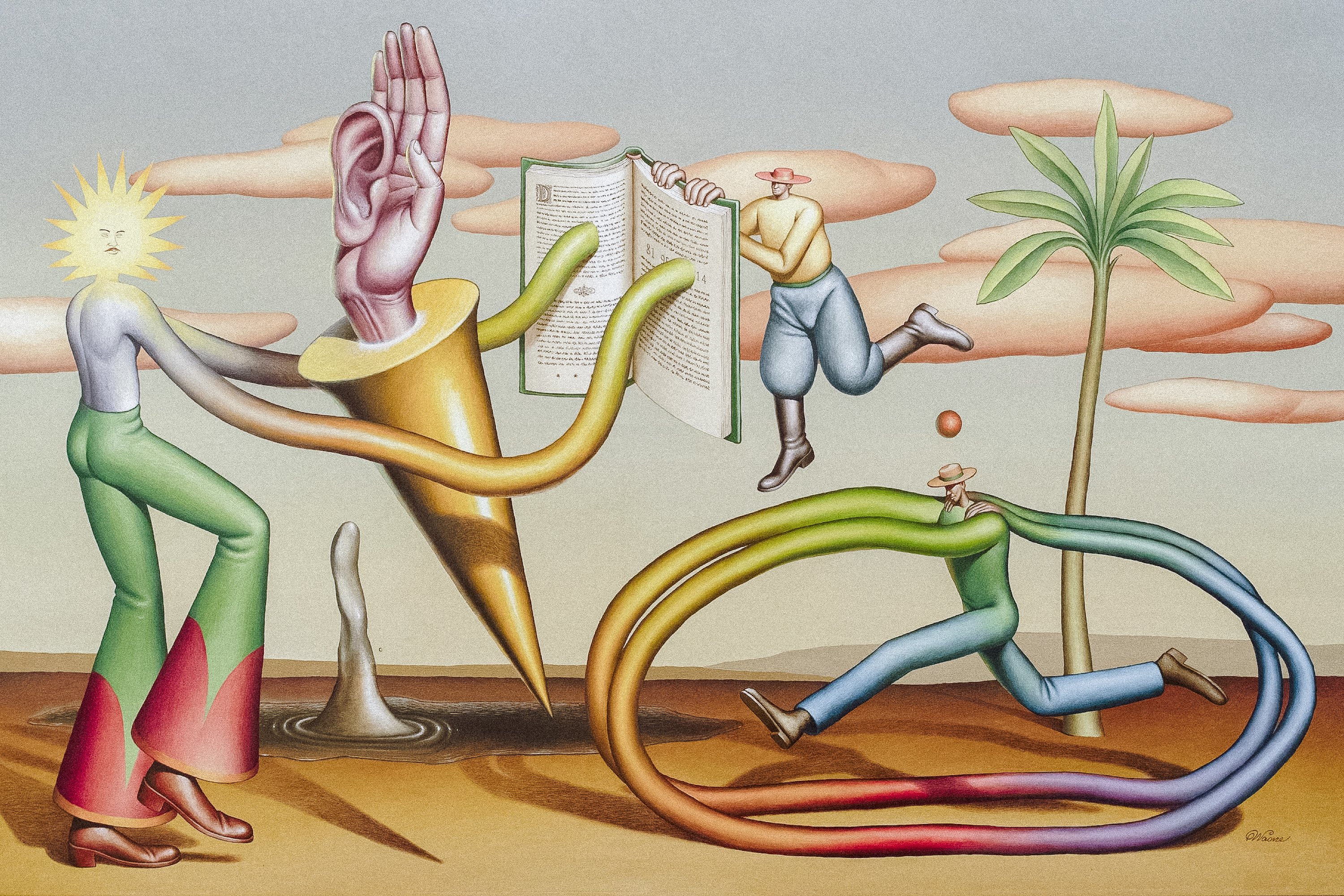

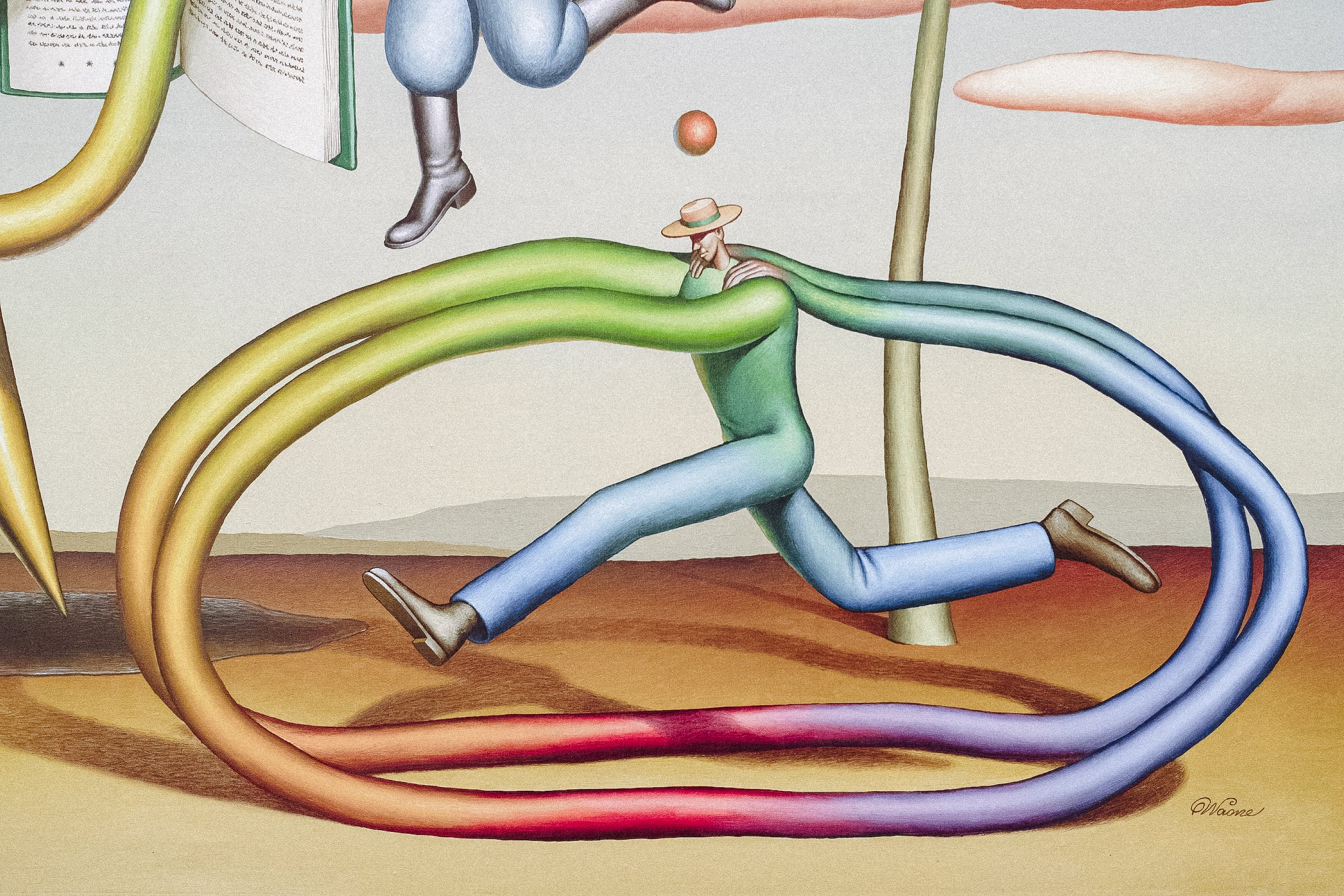

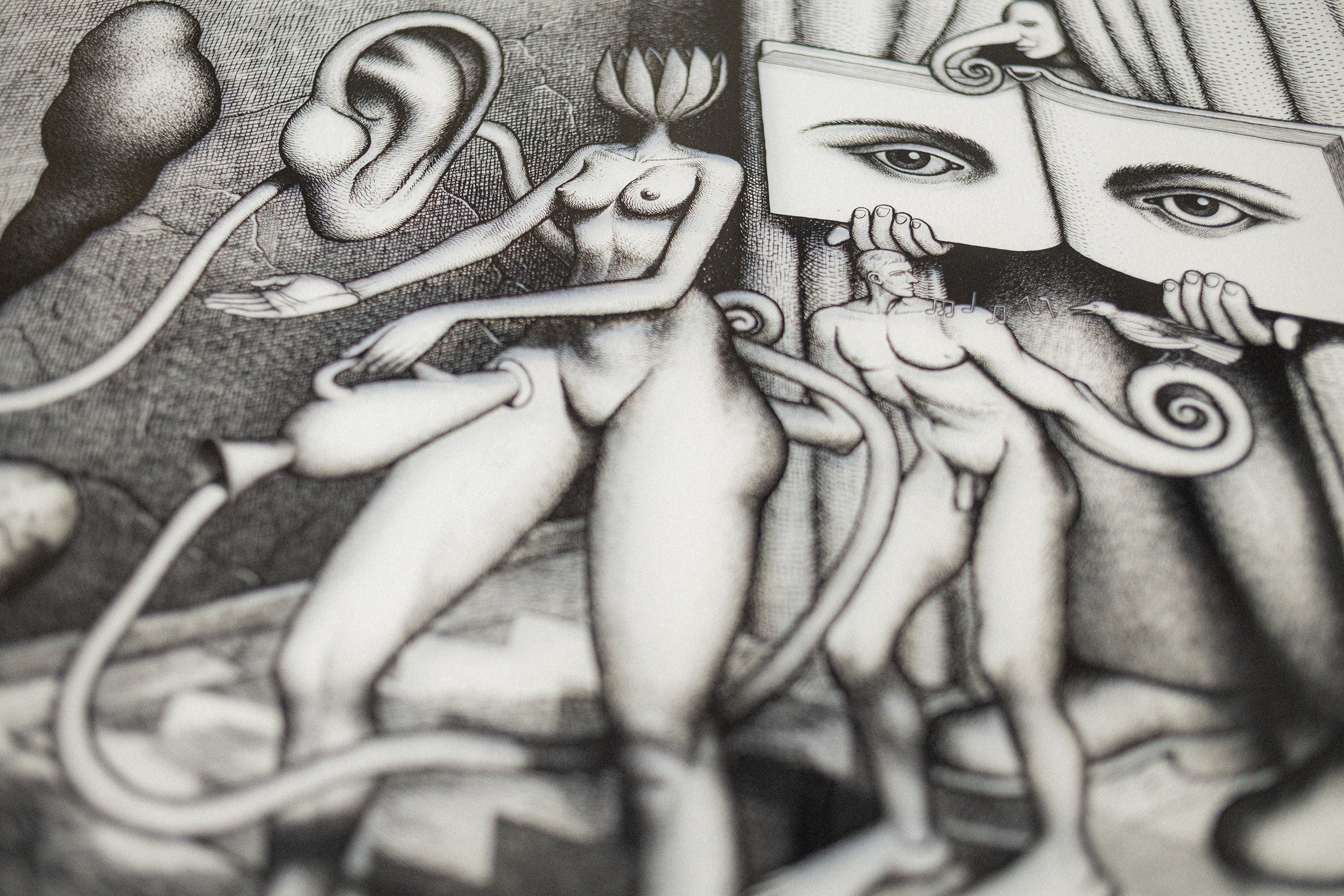

Manzhos never forgot those words — and they came true. Volodymyr didn’t just become an artist — he became a world-renowned one. He described his style as “sacred surrealism” and says the story behind each piece often begins with a single, perfectly placed detail, which feels like it was handed to him from above.

1

Volodymyr Manzhos was born in 1981 in the Kyiv region, one of three sons in the family. He spent his early years in the town of Yahotyn, where his father was the Yahotyn Poultry Plant director, at the time, one of the largest in the entire Soviet Union. In 1990–1991, his father negotiated export deals with European partners and earned commissions from those agreements.

In 1994, the family moved to Kyiv. They lived well, his father even collected art and rare Orthodox icons. The Manzhos' home was filled with art books and illustrated magazines. That’s how Volodymyr first developed an interest in art, and his father hired him a private drawing teacher.

In 1996, his father died. The family relied on savings and the sale of property for a while, until Volodymyr’s mother found work as an accountant.

After finishing school, Volodymyr enrolled at the National Agrarian University to study agricultural management. His family had connections in the industry who could help him find a job in the future. But for him, the whole experience felt like a formality. The university, he recalls, gave him neither career goals nor lasting inspiration. During his final years there, he began seriously preparing for art school, mastering academic drawing, plaster studies, and composition. But when the time came to submit his application, his mother said, “If you want it, pay for it yourself.” And he didn’t have the money. Years later, she would take pride in her son’s accomplishments and acknowledge his success.

But back then, his mother did not support her son’s fascination with street art. “Other kids are studying, getting jobs,” she’d say. “And you? Are you planning to paint fences for the rest of your life?”

Still, even then, Manzhos figured out for the first time that graffiti could actually bring in income. In 2000, he received a commission from a state-run youth organization and earned 1,500UAH, a fairly substantial sum at the time. The task was simple: paint graffiti on the wall of what used to be a Pioneer House. But what really mattered was the fact that it was his first time making money from art.

While his classmates from the Agrarian University were job-hunting in their field in 2003–2004, Manzhos wasn’t making career plans. He was painting. He earned money, then spent it all again on paint and day-to-day life. During this time, his artistic began to take shape — somewhere between tags, parody versions of Western characters, and his graphic concepts.

2

In the 2000s, graffiti culture in Kyiv began to pick up steam rapidly. By the late ’90s, it had already established itself as an important part of youth subculture, brought in from the West alongside hip-hop, raves, skateboarding, Run DMC and Cypress Hill tapes, and cult films like Wild Style and Style Wars. Graffiti became a kind of symbol of a new, free era — an alternative to the post-Soviet greyness. Around that time, the Kyiv Graffiti Club was born, the only real meeting point for street art enthusiasts. They’d gather with their sketchbooks, share styles, flip through imported graffiti mags, and swap ideas. “It was the kind of place where people could find you for commissions,” Manzhos remembers. The membership fee was 100UAH a month, but it opened up opportunities to earn money from art.

It was at the Kyiv Graffiti Club in the early 2000s that Manzhos first crossed paths with artist Oleksii Bordusov. At the time, the concept of “street art” in its modern sense didn’t yet exist in Kyiv. “There was this belief back then that painting for money wasn’t real art. ‘The ‘real’ artists were the ones who did it for themselves. But eventually, it turned out that many of these ‘authentic artists’ were just rich kids living off their parents’ money.’

Out of the dozen or so members of the club, only two, Manzhos and Bordusov, chose to team up. They didn’t consider themselves close friends, but they shared a fascination with figurative street art, had big ambitions, and saw the world the same way. Together, they began developing their distinct style: complex, figurative compositions with surreal and philosophical themes. Their style stood apart from the traditional letter-based style common at the time. That bold difference became the foundation of their partnership, and in 2005, they officially named their duo Interesni Kazki or IK.

“The name came afterwards, the style already existed,” Manzhos explains. “We needed a name that would reflect the nature of our work. The themes were surreal and symbolic, like something out of a dream or a folk myth, real fairy tales, but in our interpretation.”

As street art developed in Ukraine, a domestic market began to form itself, with clear pricing starting at $50 per square metre. Eventually, the work of Manzhos and Bordusov caught the eye of professional architects and designers. For example, the IK team received a commission to create a backdrop for the press centre at the administration of President Viktor Yushchenko.

Efforts to legalize street art often hit a wall of bureaucracy and corruption: getting a government commission usually meant handing over a kickback. So, most of the artists’ income came from private clients. Life around 2005–2006 was anything but stable: Manzhos’s earnings fluctuated from a few thousand to tens of thousands of hryvnias, sometimes with long gaps in between. But he firmly believed that street art does not answer to any system, neither politics, nor advertising or commerce. For the IK artists, their work was pure creativity, free from outside pressure or constraints.

Interesni Kazki’s first legal commission came from an advertising agency as part of a project inspired by the Cannes Lions festival. But instead of delivering a straightforward image of lions, the artists offered a surreal interpretation of the themes of inspiration and vulnerability. They painted a monkey with a drum and a Windman blowing the monkey’s hat off. The mural could be read as a metaphor of creativity and free thought that have the power to sweep away the surface-level noise of a society that behaves like a monkey with a drum. The Windman symbolizes the artist — a figure of intellectual force and vision.

In 2009, Manzhos began working internationally. In 2010, Interesni Kazki held their first international exhibition in Lyon, France, at the All Over gallery. Thanks to the growing street art festival scene, Manzhos connected with major names in the field, including JR and Wheels. In 2011, the team presented their work at a show in Milan’s Avantgarden Gallery, which focused exclusively on street art. That same year, Manzhos and Bordusov received an invitation to take part in Wynwood Walls in Miami — one of the world’s most iconic mural projects. Its founder, Tony Goldman, had purchased a local industrial zone with the vision of transforming it into an art hub and a prime real estate destination.

Projects in the United States proved that street art could be a powerful force for the cultural and economic transformation of struggling neighbourhoods. Investors often bought up entire blocks of rundown properties, and by inviting in street artists and graffiti, they boosted the area’s appeal and its market value accordingly. Back in the 1960s to ’80s, fees for such projects could reach $50,000–100,000, whereas in the 2000s, Manzhos says they were getting only $5,000–10,000. Spray paint had made the process faster and cheaper, and street art more accessible and mainstream. A new wave of projects emerged as artists began using acrylic paints, allowing for more complex compositions, textured surfaces, fine details, and longer-lasting results.

In 2014, as Russia launched its first wave of armed aggression against Ukraine, Manzhos and Bordusov responded with a mural series called Time of Change. The first mural was painted in Kyiv on Striletska Street, the second — in Poland, initiated by the European Parliament, and the third was created for Ukraine’s Armed Forces. The symbolism across the series was clear and consistent: a bear, chasing a yellow-and-blue beehive, falls into an abyss, while a Ukrainian Cossack, dressed in the uniform of the Armed Forces, delivers the final blow. “These works are about choice, resistance, and the point of no return,” the artist says.

Even art created to bring people together can run into unexpected resistance. “Most of the time, when people see me working, their attitude is incredibly warm — they stop by, ask questions, say thank you,” Manzhos says. But in Morocco, he faced open protest for the first time. Shouts came from the crowd when they saw a figure in the mural standing on a book. For many Muslims, any book is symbolically associated with the Quran, making such an image deeply offensive. It was the result of an oversight by the organizers, who — despite having the sketch approved by local authorities — failed to account for cultural sensitivities in interpretation. An artist must be sensitive not only to form but also to the cultural memory of the space in which they are creating,” Manzhos concludes.

Volodymyr recalls that during this period, thanks to their murals, their name became known in major art hubs throughout North America and Europe. Curators began recognizing them as part of the “first wave” of modern Ukrainian muralism.

But in 2016, Interesni Kazki came to an end — each artist chose to follow their own path. Waone went on to pursue a solo career.

3

After 2015, mural art started to become too commercial, tailored to mass audiences and social media. Success started being measured in Instagram likes, and the deeper meaning of works gradually gave way to generic portraits and decorative facades. What began as a form of protest and artistic independence turned into a marketing tool.

That shift hit Manzhos with a creative crisis. A turning point came with his participation in the German project Stand Wand Kunst. At a time of deep personal and artistic uncertainty, this experience brought an internal transformation. The experience pushed him to see murals and art as a whole, in a new light.

Manzhos searched for spirituality in many forms — through yoga, vegetarianism, trips to India, and Christianity. “My spiritual journey wasn’t a straight line,” he says. “I spent time in Protestant churches, explored Krishna consciousness, and found my way to Orthodoxy through family tradition and my interest in a priest who became a role model for me. That’s how my personal mix of beliefs and artistic practices came together,” Manzhos explains.

In the fall of 2017, director David Lynch came to Kyiv to present his Transcendental Meditation Foundation, an initiative promoting meditation and supporting war veterans, refugees, and survivors of domestic abuse. At the event, Manzhos met Lynch, and their brief 15-minute conversation left a deep impression on him. Lynch didn’t just talk about meditation — he embodied its effects. The sense of calm and inner harmony he carried seemed to ripple through the room, touching everyone there.

Meditation became a turning point in Manzhos’s life, dividing it into “before” and “after.” It allowed him to engage more deeply with his work and protected him from burnout. After meeting Lynch, Manzhos became even more interested in Lynch’s work as an artist. This eventually led him to Paris, where Lynch had worked at the legendary lithography studio Idem Paris, a space once graced by legends like Picasso, Matisse, Chagall, and Miró. Through his connection with French artists, including Julien Malland, Volodymyr met the studio’s owner and began collaborating with them. He set out to expand his artistic practice beyond street art into traditional printmaking. “I sent one of my works to Christie’s auction — 20,000 euros from the sale went toward securing and preserving the property of the Idem Paris studio.”

In February 2017, the artist took part in a group exhibition at Kreisler Gallery — one of the most influential contemporary art galleries, which had previously exhibited works by Picasso. Though he never received a classical art education, Waone mastered his own style and technique independently, often spending up to 10 days creating a single mid-sized piece.

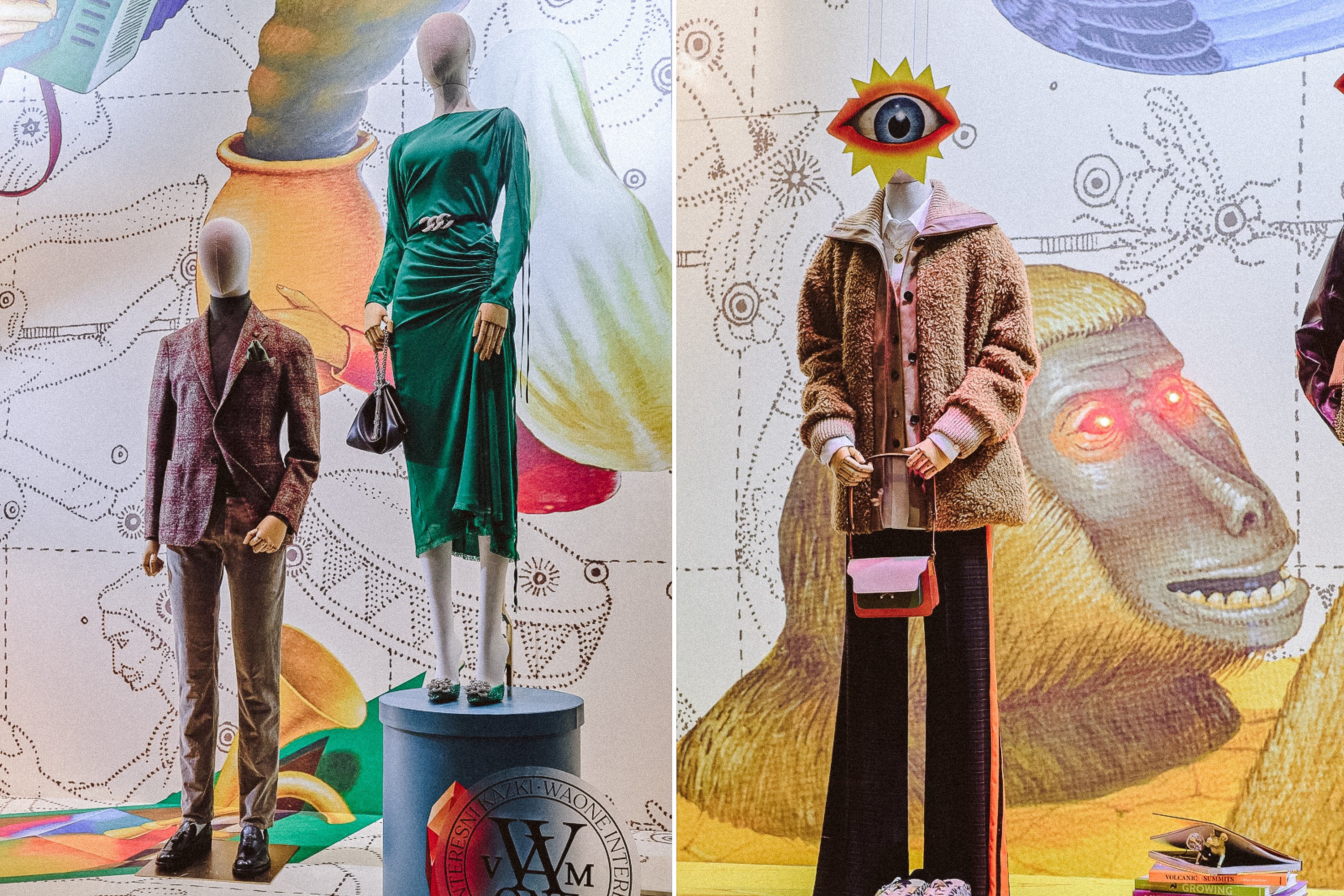

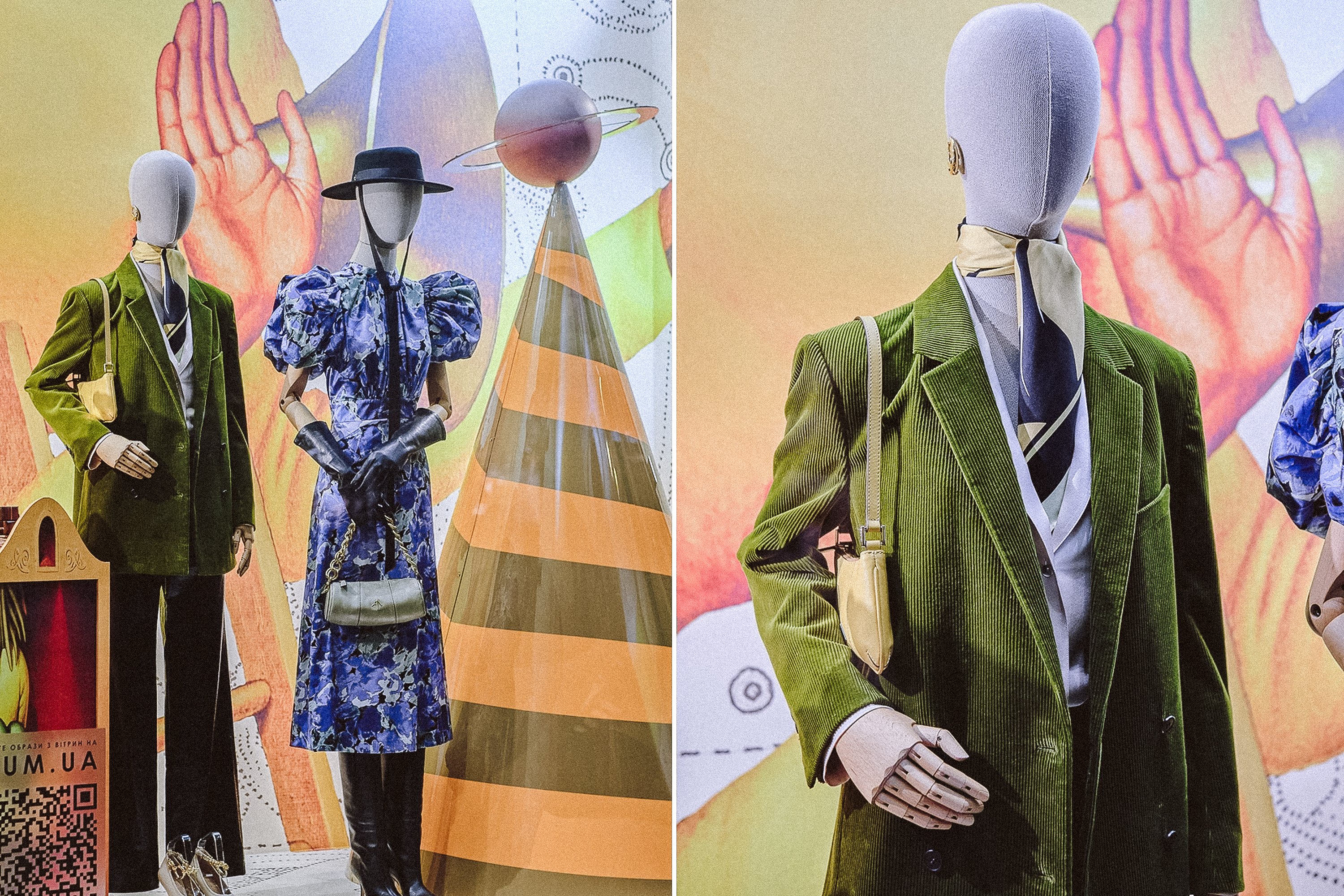

By 2020, Manzhos was comfortably making a living from his art — painting, ceramics, and graphic work. The pandemic helped him focus on this direction. For instance, filmmaker Darren Aronofsky approached him with a request to create a large-scale piece for his home. This wasn’t Manzhos’s first experience with visual design for displays. In 2021, he created surreal window installations for Kyiv’s TSUM department store. Each window featured surreal imagery blending mysticism and science: a winged tiger, a red-eyed glowing monkey, musical instruments, as well as playful and geometric forms. All the works were tied together by a single visual theme — a pattern of the starry night sky.

4

In 2021, Manzhos had earned enough to buy his own home in Kyiv. But just a year later, war broke out. That’s when Idem Paris offered him a permanent residency. “They told me, ‘Stay and work,’” the artist recalls. Idem Paris is one of France’s oldest print studios, founded in 1880 and famous for hosting artists like Picasso, Matisse, and Miró. The studio has preserved its unique 19th-century presses and still produces lithographs by hand.

At the same time, Manzhos also received an invitation from Arte, a print studio established by the Mourlot family, a legendary French dynasty of fine art printers. His life soon became split between two cities — a month in Paris, a month in Kyiv.

In April 2023, Volodymyr Manzhos joined the international art project ART ON THE BATTLEFRONT, initiated by Vogue UA. Blending media, digital tools, and contemporary art, the project aimed to support Ukrainians in wartime and spotlight the power of cultural resistance. The project culminated in an exhibition held in the heart of Vienna, at the historic Künstlerhaus. Proceeds from the project were donated to a rehabilitation fund for women in the military, created by the Ukrainian Veterans' Movement.

Later, Hermès approached Manzhos with a major commission — a window installation made of plastic sculptures, 3D-printed and hand-painted. Hermès, founded in 1837, is one of France’s most legendary fashion houses, with its in-house art department and a deep commitment to artisanal craftsmanship. The company regularly invites artists from around the globe to design window displays in cities like Paris, Tokyo, New York, and Shanghai.

Hermès didn’t assign a specific title to the installation, but the concept aligned almost perfectly with Waone’s visual universe. One scene showed a musician playing a nighttime tune under a glowing streetlamp; another evoked the calm of a surreal beach. Manzhos spent 14 months bringing the project to life. The result was striking. Though Hermès typically doesn’t host formal unveilings for its displays, this particular case became a milestone in the artist’s career. While the details of the contract remain confidential due to signed agreements, Manzhos notes the fee was in the tens of thousands of dollars.

5

Volodymyr Manzhos is currently working with the Ukrainian brand Etnodim on a unique line of embroidered clothing that merges Ukrainian traditional aesthetics with the artist’s distinctive artistic vision. But it’s not simply about transferring elements from canvas to fabric. “You have to rethink form, colour, rhythm,” the artist explains. “You can’t just take an object from a painting — it has to be adapted for embroidery. That’s a real challenge for me.”

The Etnodim project isn’t your standard commercial fashion line — it’s a limited edition series where every piece has a unique, non-repeating design. These are, in essence, wearable art objects — a fusion of fashion, fine art, and national identity.

Demand for Manzhos’s original paintings remains consistently high. His waitlist stretches months ahead — and most orders aren’t prints, but custom works created for specific clients. “I work every day from 10 a.m. to 7 p.m. I often manage up to three paintings at once, while also printing graphics, sculpting, and working with ceramics,” the artist shares. Manzhos reinvests much of his earnings into the production of bronze sculptures, a costly but deeply meaningful direction for him.

Since 2023, he’s been tracking his income closely to understand his creative business potential. “On average, I make about $10,000 a month,” he explains. “One month, it hit $50,000 — right after the Hermès installation went viral on social media. Almost everything I had available, both online and in the studio, sold out.”

Today, Manzhos is setting a new long-term goal — to create a personal museum in Europe. But he’s not just thinking of a gallery space. His vision is for a dynamic cultural hub where his artistic language blends naturally with the surrounding landscape, local architecture, and community.

After February 24, Manzhos clarified a long-standing inner dilemma: should art reflect reality? “I came to understand that I don’t have to channel pain through my paintings, prints, or sculptures — there’s already more than enough of that in the headlines,” he says. “My role is to create something intuitive and sincere, free from the pressure of external context. I deeply feel every social and political upheaval, but I prefer not to respond to them directly, except when it comes to murals. Street art, to me, is a way of showing solidarity.”