Maria Shchedrina is a native of Cherkasy. She graduated from a Gymnasium with an in-depth study of foreign languages and later received her first degree in applied linguistics. After that, she went to Frankfurt am Main, where she obtained her second Master’s degree.

During her studies, Maria completed an internship in Singapore and made a decision to stay there to teach German at one of the universities. Later, she taught Ukrainian to Singaporeans, bridging cultures through language and education. In 2022, she decided that her future children should know the Ukrainian language, and therefore, in 2024, she published “Vulyk” (“The Beehive”) — a textbook for teaching Ukrainian to bilingual children. Currently, Maria is pursuing her PhD online and working on the second part of her book.

YBBP journalist Mila Shevchuk spoke with Maria about the textbook creation, the Ukrainian community in Singapore, local fines, and the phenomenon of Kiasu, which shapes the local culture of striving for supremacy in everything. The main talking points are below, and the full podcast episode is available here.

I have three phases in my life: Ukrainian, German, and Singaporean. I obtained my first Master’s degree at the Cherkasy State Technological University. Just four months later, I moved to Germany, where I got a Master’s degree in Comparative Linguistics. There, we studied how languages evolved, their origins and history, and the methods used to compare them. If a manuscript in an unknown language were to be discovered during an archaeological excavation, specialists in this field would be able to interpret it.

I happily started learning my first foreign languages at the age of four, seven, and nine. When I was four, my mother went to Egypt and was so embarrassed that she didn’t speak English that she made a decision: her daughter absolutely must know the language. Once she returned to Ukraine, she found me a tutor.

When I was seven, my parents sent me to Spain, convinced that everyone in Europe spoke English. To their surprise, the family I stayed with for 40 days didn’t speak a word of it. Immersed in their world, I began to pick up Spanish words and phrases like a sponge. By the time I returned home, I could chat fluently on the phone in Spanish. My parents were so amazed that they invited a teacher to make sure I wasn’t just inventing the words. The teacher confirmed that my Spanish was real, and encouraged me to keep learning.

When I was nine, I had to choose a third foreign language at the gymnasium. I settled on Japanese, but I have only used it twice in my life — during my trips to Japan.

I studied at one of the oldest Gymnasiums in Ukraine, whose proud motto is “The First is always the first.” Even during the Soviet and Imperial eras, when Ukrainian was often suppressed, the language continued to be taught there. It’s hard to explain to foreigners that, at the time, education in Ukrainian was a rarity. I was born in 1991, the year Ukraine regained its independence, and our teachers often reminded us that we were the first generation of independent Ukrainians, that we had to be well-educated and multilingual, because we were the ones who would represent Ukraine to the world.

By the time I completed my Master’s degree, I knew five foreign languages, having also studied German and French at university. Later, at the Faculty of Linguistics in Frankfurt, I began learning Old Church Slavonic and Ancient Greek, though I don’t count them as they’re considered dead languages. I also studied Modern Greek for two years, but since I haven’t practiced it, most of it has faded over time.

I began my main professional career in Singapore. While studying linguistics in Ukraine, I worked as an English and Spanish teacher and served as a translator for a television project in Argentina. In December 2016, I came to Singapore for a six-month internship at a German school, never expecting to stay. But I quickly fell in love with the country and decided to build my career here.

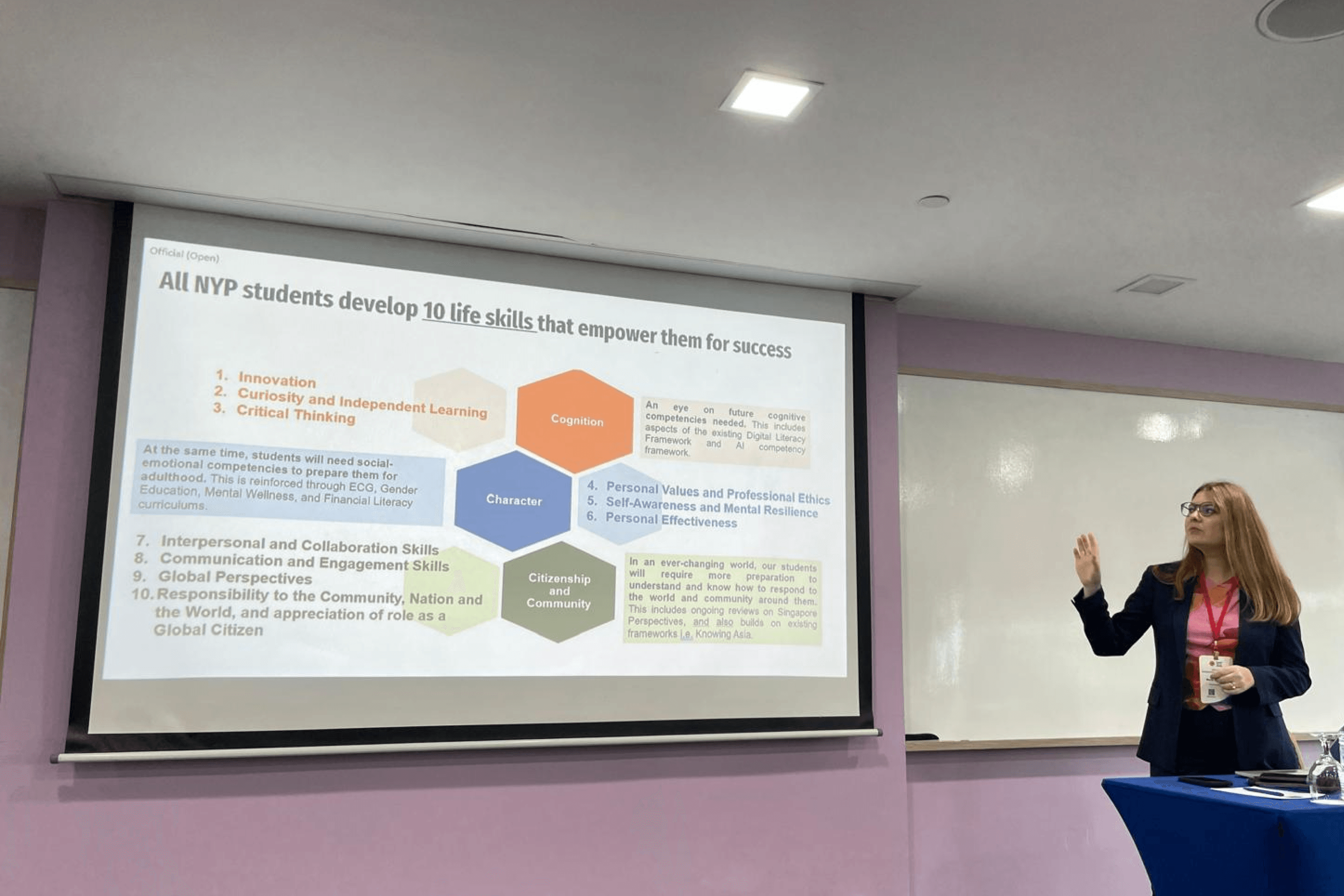

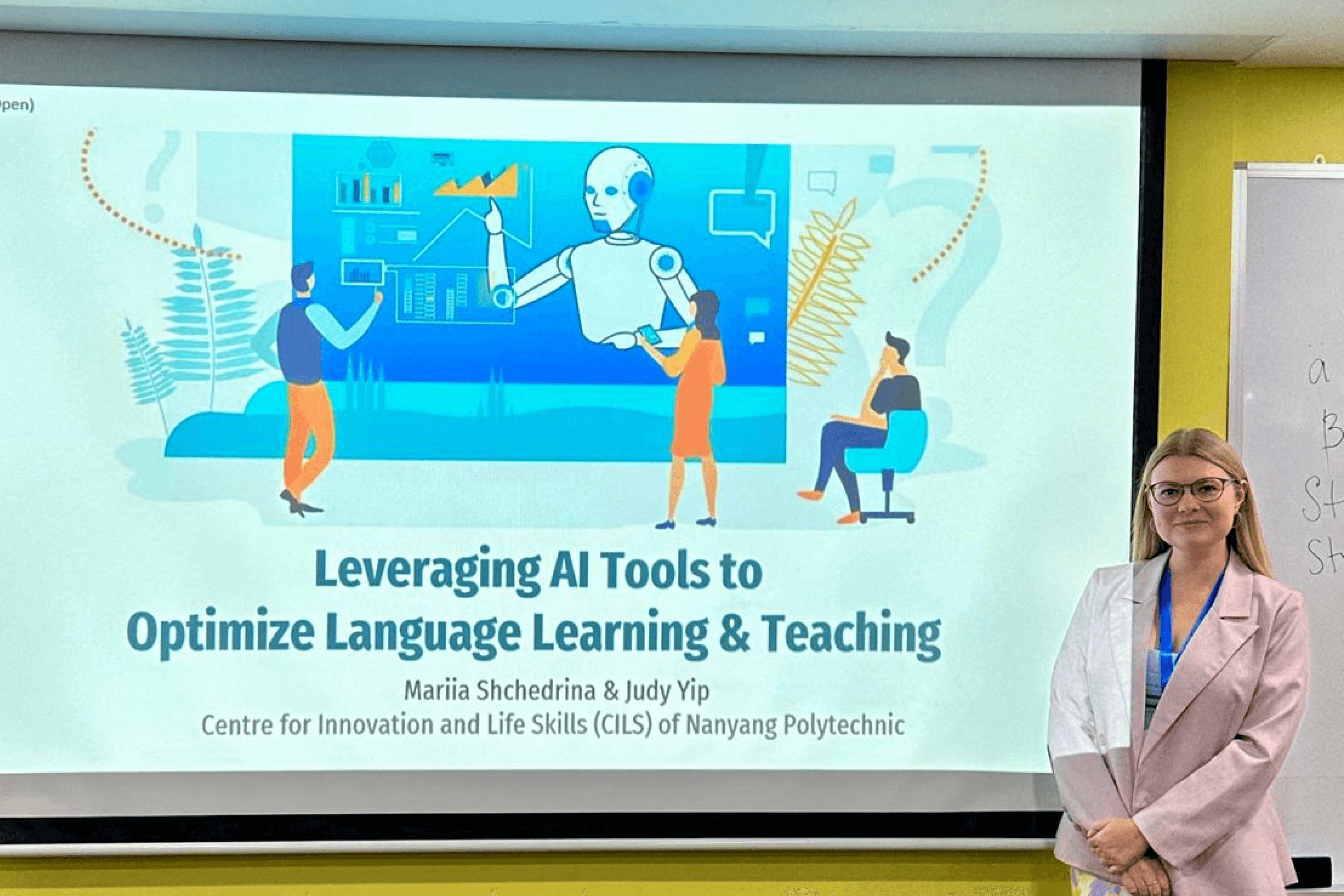

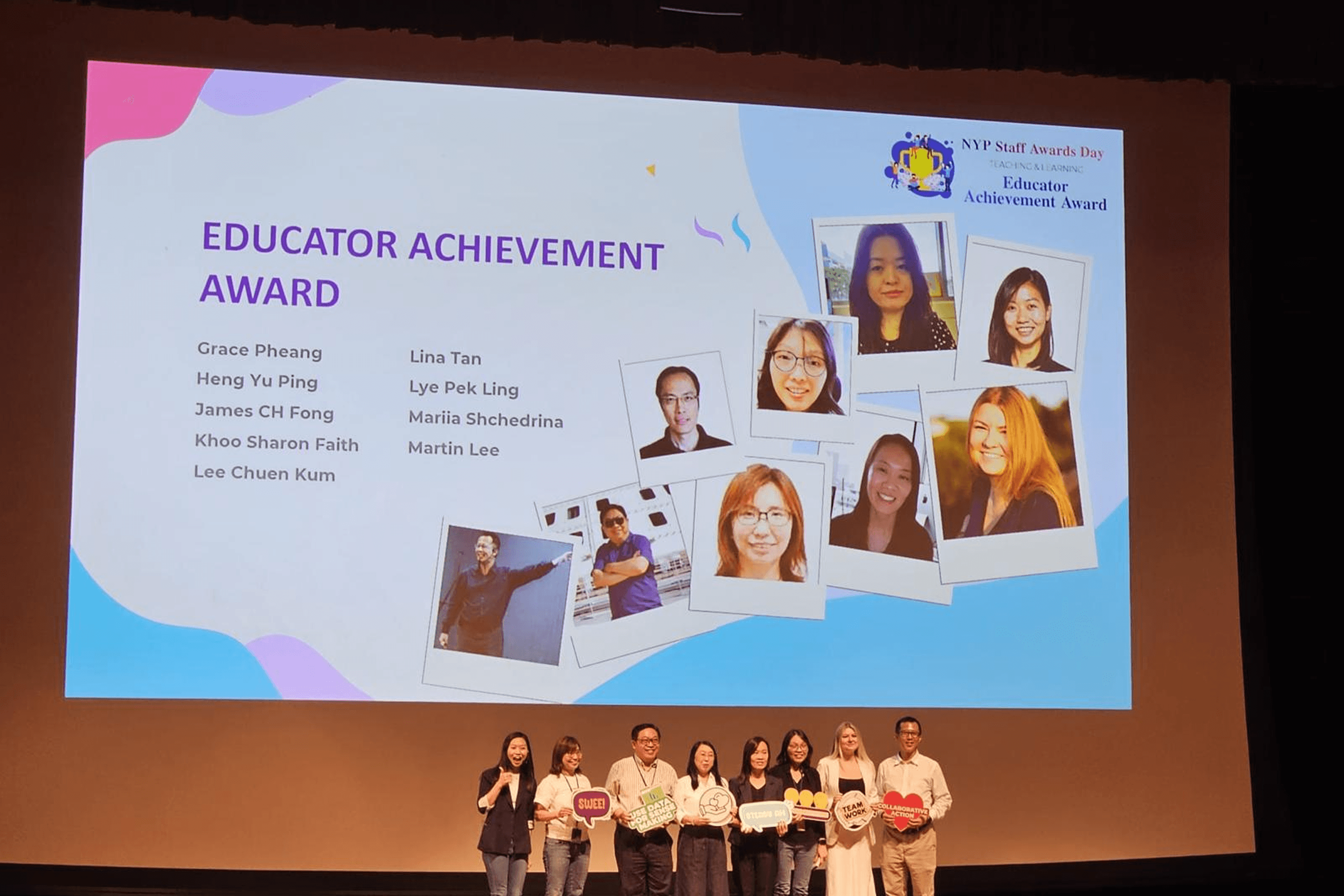

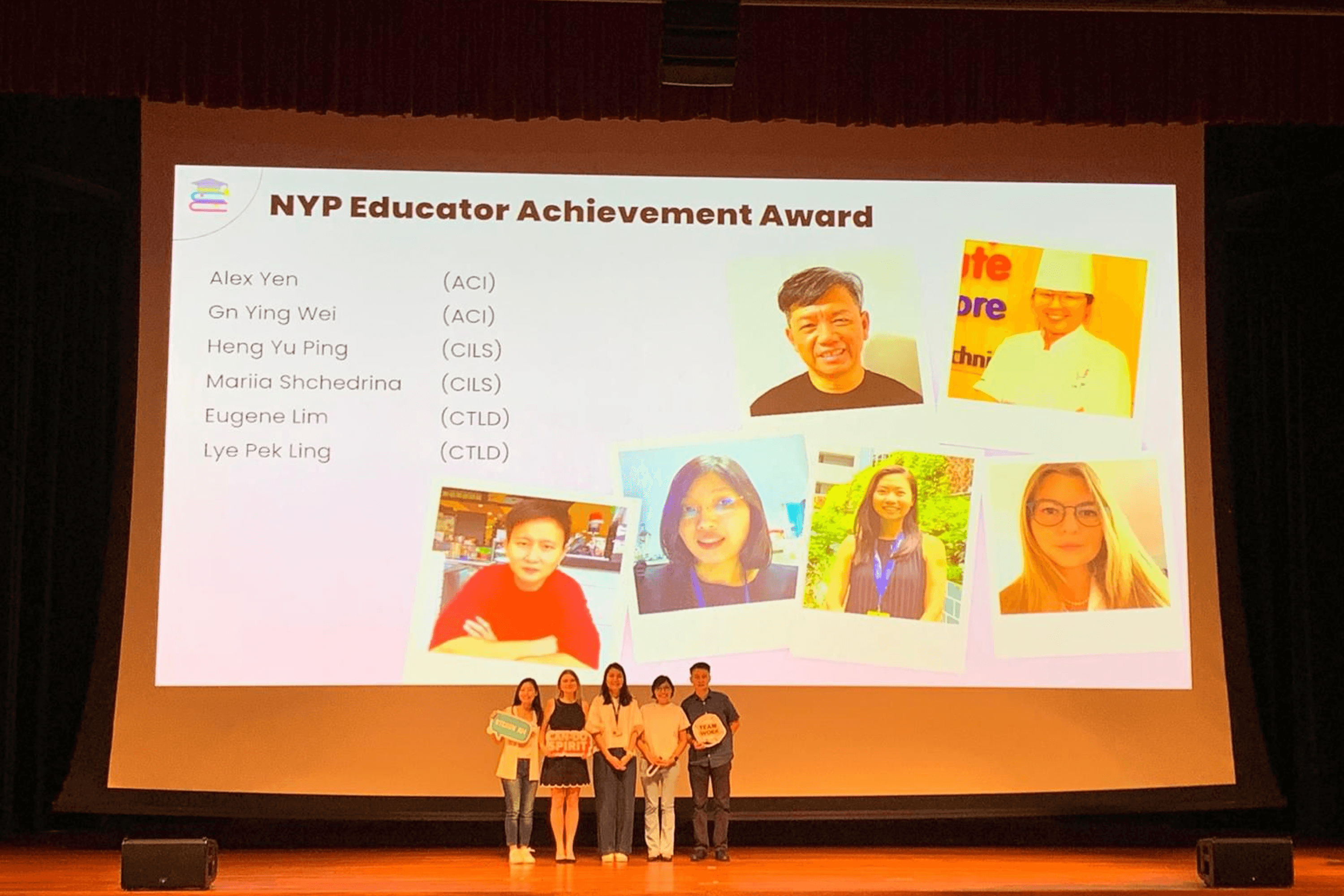

At first, I taught Ukrainian and Russian at a language school while also teaching German at the National University of Singapore. For four years, I juggled multiple teaching roles until the constant pace finally became overwhelming. That’s when I decided to move to Nanyang Polytechnic, where I have now been teaching German for five years. In addition, I teach modules on Gender Inequality and Sexual Misconduct, for which I completed training in Singapore.

It’s not easy to get into Singapore or secure a work permit, but I was fortunate. In Frankfurt, I often felt unwell and worn out by the endless grey days, and I longed for a change. One Sunday, while watching a travel program about Singapore, I felt inspired and decided to look for opportunities there. The next day, I came across an advertisement for a German language intern. It was open to students from German universities. It was my final semester, so I applied immediately. Two weeks later, my invitation to come to Singapore was approved. I had sent only one résumé, not realizing that others were submitting hundreds in hopes of the same chance of coming to Singapore.

There are four official languages here: English, Chinese, Malay, and Tamil (the language of southern India where the Tamils live). The only national language is Malay, after all, Singapore was once a part of Malaysia. I only communicate in English, as everyone here, from children to the elderly, knows it well, so there was no need to learn other languages.

Singapore is a country that gained independence not out of choice, but out of circumstance. In 1965, Malaysia declared that Singapore was too problematic to govern and decided to expel it from the federation. During a live television broadcast, Singapore’s then Prime Minister, Lee Kuan Yew, announced the nation’s independence, and wept as he spoke. Nearly sixty years later, Singapore stands among the world’s most successful and forward-looking countries.

I knew that Singapore was a country of rules, and that didn’t scare me away. I love order and I felt comfortable even in structured Germany, so I easily accepted the local norms. There are indeed many fines in Singapore: for feeding pigeons, playing loud music on the street, making graffiti, unauthorized connection to Wi-Fi, or even nudity at home. The chewing gum trade is prohibited; dental gum can be purchased only with a prescription. E-cigarettes are equated to drugs, and their sale is punishable by the death penalty.

Even nudity in your own apartment can be considered a violation if you’re visible from the street. The country’s multicultural society, made up of Chinese, Malay, and Tamil communities representing various religions, places strong emphasis on public decency and social harmony. With residential buildings often situated close to one another, it’s easy for neighbors to be seen accidentally. And if such an incident is caught on video, a complaint can be filed with the police.

The fine may be 500 Singapore Dollars (SGD). Only local currency is used here — there is no habit of converting to other currencies. The amount depends on the circumstances and whether it is the first violation. Repeated offenses can lead to imprisonment or caning.

The crime rate here is remarkably low, and the cost of living is among the highest in the world. It’s an exceptionally safe country, with surveillance cameras almost everywhere. In cafés and public spaces, it’s common for people to leave their wallets or phones on the table to reserve a seat, without any fear of them being stolen. Singaporeans are generally very kind, law-abiding, and respectful of others. Perhaps an anthropological study could explain this phenomenon: whether it stems from deep-rooted social values or from the pervasive system of fines and the fear of punishment.

Foreigners in Singapore pay a 60-65% surcharge when purchasing real estate. For example, if a condominium apartment costs 1 million SGD, a foreign buyer would need to pay 650,000 SGD tax to the state simply due to their non-resident status. Those with Permanent Resident (PR) status are exempt from this tax or pay 5%. There are no additional taxes on rental properties, though rental prices vary by district. On average, a one-bedroom apartment costs between 4,000 and 5,000 SGD per month.

Singapore avoids social tensions by maintaining a balance among its ethnic groups, permanent residents, and foreign residents. It is believed that granting residency disproportionately to one nationality could disrupt this equilibrium. Applications for Permanent Resident status are reviewed over several months, and the government does not disclose its selection criteria, making the process feel somewhat like a lottery. Even wealthy or highly skilled applicants may be rejected without explanation.

In Singapore, PR status is regarded as a privilege rather than a right. Quotas are limited, and tens of thousands of applications are submitted each year. The authorities often reject applications during the first few years perhaps to test an applicant’s commitment to staying in the country. Priority is given to candidates with strong professional qualifications, a stable income, and a long-term employment contract. Investors who contribute between 10 and 20 million SGD through approved schemes may obtain PR after fulfilling specific investment requirements.

If your contract ends or you are fired, you must leave Singapore within a month, sometimes within two. Due to this requirement, many of my friends have left the country. In the allotted time, a person has the right to find another job; in that case, they change their visa and stay.

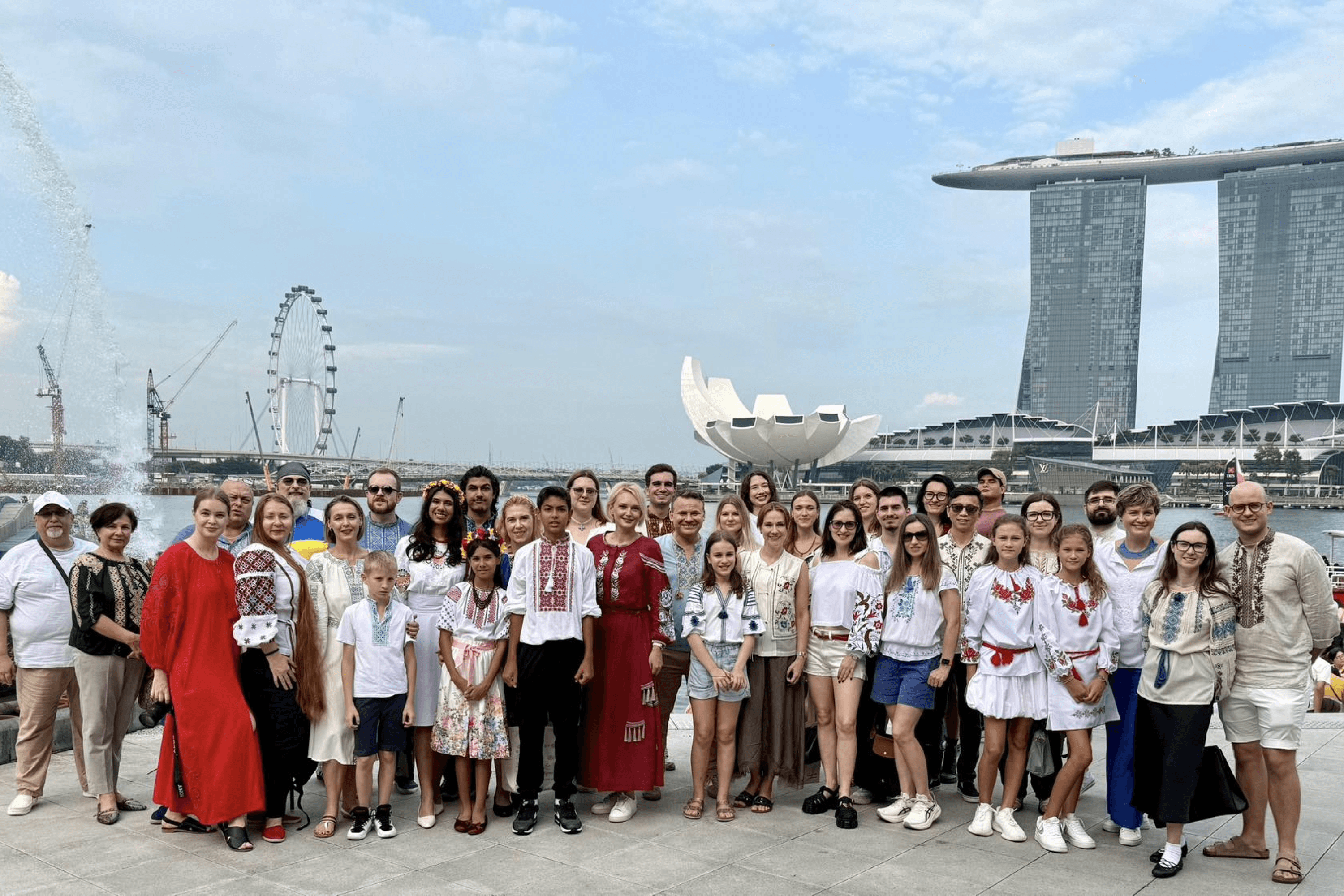

Statistics by nationality are not published here. When the Ukrainian Embassy asked the Singapore Ministry of Foreign Affairs about the number of Ukrainians in the country, it refused, citing privacy concerns. According to press estimates, there are about 500–800 Ukrainians living in Singapore. There is an active Ukrainian community and club here; they regularly organize film screenings, exhibitions, and charity fundraising.

In Singapore, demonstrations are permitted only under strict conditions, without flags, slogans, or placards. Public gatherings are tightly regulated, and organizing rallies or marches requires police approval. Certain sensitive topics are also off-limits. Foreign flags may be displayed only on embassy premises, so we can see the Ukrainian flag only in Raffles Place. If I were to hang a Ukrainian flag from my balcony, I would be fined, as such displays are prohibited.

The Singaporean concept of kiasu can be described as a kind of state-level perfectionism. The word kiasu, borrowed from the Hokkien dialect of the Chinese language family, literally means “to squeeze the maximum out of everything.” This mindset is deeply ingrained in Singaporean culture. The nation is constantly striving to outperform others and remain at the top. While this relentless pursuit of excellence is not always healthy, it undeniably drives progress and innovation.

Singapore closely observes developments in places like Hong Kong and Dubai, often aiming to surpass them. This ambition is carried by a population of about 6 million people, roughly 1.5 million of whom are expats. The government openly acknowledges that the country relies on foreign specialists, as its domestic talent pool alone cannot meet the demands of its growing economy.

The pressure of kiasu is felt everywhere in Singapore: both in society and at work. When departments plan their yearly goals, every employee is assigned numerous tasks and projects, each striving to make their team among the best. This culture motivates people to work harder, as excellence is built into institutional policy. Even in casual conversations with friends, subtle comparisons often arise: about who traveled where, what they achieved, or what they could afford. And inevitably, the thought follows: “I need to work harder too.” Depending on one’s mindset and emotional resilience, this can be either a powerful motivator or a source of stress.

I feel my own kiasu too: balancing work, PhD studies, and writing a book. It’s not easy to fit everything into a single day, but I genuinely love what I do, and that passion gives me the strength to keep moving forward.

The suicide rate among teenagers in Singapore remains a serious concern. Many young people struggle to cope with the intense academic pressure from both their parents and the highly competitive environment. From an early age, students are expected to excel: to top every ranking and achieve perfect grades. For some families, especially those with parents who studied at prestigious universities like Harvard, Oxford, or Cambridge, anything less than excellence feels unacceptable. In such a demanding system, a single disappointing grade can feel devastating. Tragically, several students from leading institutions such as the National University of Singapore and Nanyang Technological University have taken their own lives under the weight of these expectations.

Since 2019, I’ve been volunteering to teach Ukrainian to Singaporeans on weekends. It all began when a group of local students who knew me as a linguist asked me to run a beginner’s Ukrainian course. Soon after, the Ukrainian Embassy began recommending me to anyone interested in learning the language. In 2022, following the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion, many Ukrainian families reached out, asking me to teach their children. But at that time, I simply didn’t have the strength. Teaching is never easy: it requires giving your whole self, 100%, and sometimes, the energy you give out doesn’t come back. You go home drained, both physically and emotionally.

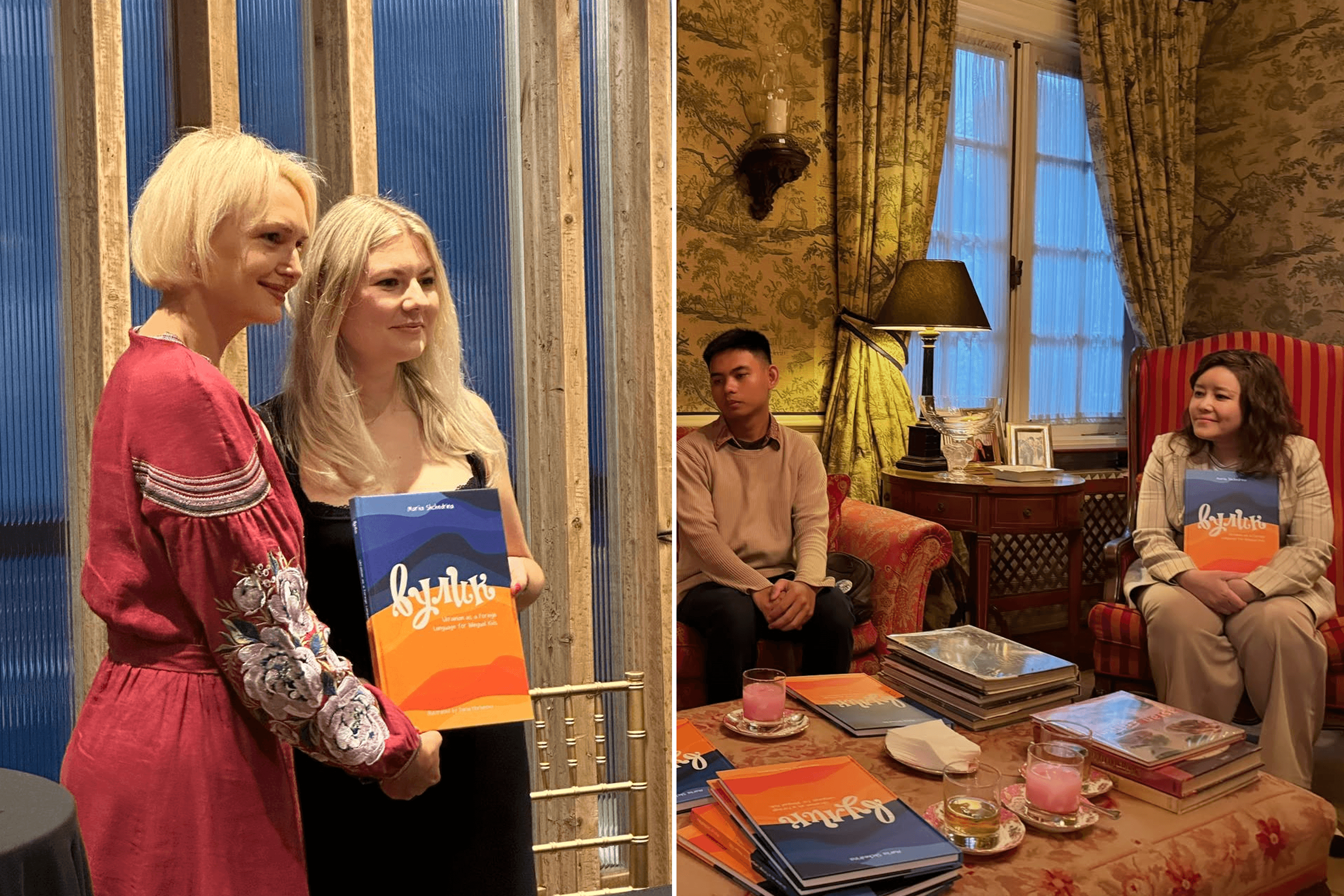

In 2022, our community opened a Ukrainian Sunday school in Singapore. Ukrainian mothers taught there, though most had neither pedagogical nor linguistic training. I decided to help by creating teaching materials for them. Later, I realized that one day I might also have children born outside Ukraine, and I would want, of course, to pass my native language on to them. That’s how the idea for my textbook was born — for my future children and for those growing up in Singapore. Here, many families are mixed: Ukrainian-Chinese, Ukrainian-French, Ukrainian-English, and many others. Their children often understand Ukrainian but don’t think in it. I wrote “Vulyk” specifically for bilingual children, for whom Ukrainian is, in many ways, a foreign language.

This book is designed for children aged 3 and above and features beautiful illustrations by Daria Horiunova from Cherkasy. Parents can look through the pages together with their children and talk about the characters: what they’re wearing, what colors they have, and what stories they might tell. The illustrations invite play and spark imagination, even without reading a single line. Dasha and I spoke on the phone only three times, yet it was a remarkable creative symbiosis. She intuitively understood what to draw and which characters to bring to life. Together, we completed the text and illustrations within a year.

By law, I am not allowed to be an entrepreneur, as I work in the public education sector — I teach at one of Singapore’s five polytechnics, where teachers are civil servants. Therefore, I officially informed my workplace that I had published a book and planned to sell it and declare everything. I self-published the textbook at my own expense and registered it as a Singaporean publication. It received an international library number (ISBN) from the National Library of Singapore. I printed one thousand copies in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, where printing costs were lower. The entire process from registration to production took about six months to complete.

Parents can easily teach their children Ukrainian with this textbook. All the rules are explained in a simple, approachable way; it’s meant for beginners. In the first volume, I focused on the nominative, accusative, prepositional, and dative cases. The rest will come in the second volume, once I finish my PhD. My thesis explores how AI is used in Singapore’s educational institutions. The Ukrainian language is undeniably complex, but I’ve always loved grammar, and creating exercises that make learning it a little easier gives me real joy.

I presented my book at Ukrainian schools in Indonesia: both in Bali and in the capital, Jakarta. The textbook has already been adopted by Ukrainian Sunday schools in Germany and Dubai. I also sent around 50 letters to Ukrainian schools in the United States but received only one reply. In Singapore, however, the Ukrainian community is incredibly supportive. Embassy staff attended my book presentation, and many parents bought copies for their children and friends. Others helped with deliveries, since shipping from Singapore is expensive: the book itself costs 50 SGD, and delivery adds another 35 SGD. That’s why I’m always looking for people traveling to Europe or the United States who can help send books from there.

If you are a foreigner, your child doesn’t have the right to attend a local school. Foreigners' children can only study at international schools, where a year costs from 15,000 to 30,000 SGD. There are two main education systems in Singapore: the International Baccalaureate (IB) — US and EU-oriented — and the British system. Only children of foreigners with Permanent Resident status can attend local schools. School education lasts from age 7 to 19, after which all boys from permanent resident families undergo two years of military service. Therefore, girls usually enter universities at 19, and boys at 21.

In Singapore, foreign children are not eligible to attend local schools. They can only study at international schools, where annual tuition fees range from 15,000 to 30,000 SGD. The country primarily follows two education systems: the International Baccalaureate (IB), which is aligned with the US and EU, and the British curriculum. Only children of foreigners with PR status are allowed to enrol in local schools. Formal education typically runs from age 7 to 19, after which all boys from PR families must complete 2 years of compulsory military service. As a result, girls usually enter university at 19, while boys begin their studies at around 21.

Singaporeans pay less for university education than foreigners. A full degree program can cost around 50,000 SGD. There are numerous subsidies and scholarships available to local students. If you are a talented Singaporean, the government may even fund your studies at some of the world’s top universities, such as Harvard or Cornell. However, this support comes with a condition: after graduation, recipients must return to Singapore and serve in the public sector for 4 to 5 years, often rotating across different ministries.

For a child to learn your language, it takes dedication, the steady effort of one or both parents. A child should be exposed to all the languages their parents speak; there is no real limit to the brain’s capacity to absorb them. Always speak the language you feel most connected to, and the child will absorb it naturally. They may not respond in the same language right away, but don’t lose hope; keep going. One day, they will speak. There are children in Singapore, born to mixed Ukrainian families who have never set foot in Ukraine, yet they speak Ukrainian perfectly. That’s the result of their parents’ commitment, an ongoing effort that keeps a language alive far from home.

After completing my PhD, I plan to create a series of textbooks on Ukrainian culture, covering music, literature, and art. These books will be written with simplified vocabulary for bilingual children around the world. Each book will serve as a mini-encyclopedia, combining engaging cultural content with exercises that develop both Ukrainian language skills and general knowledge.