On February 5, 2022, gallerists Yuliia and Maksym Voloshyn opened their «The Memory on Her Face» exhibition in Miami. The project told the story of the war that began with Russia’s aggression in 2014 and forever changed the lives of Ukrainians. They had planned to return to Kyiv afterward. However, just 17 days later, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, turning their exhibition into an unintentional yet powerful artistic statement. Their plane tickets to Kyiv were never used. Back home, their gallery on Tereshchenkivska Street became a shelter for artists, while they remained in the U.S., adjusting to a new reality. Their work did not stop, they continued their mission of promoting Ukrainian art but now on a larger scale. Over nearly two decades, the Voloshyns have been the driving force promoting Ukraine’s art on the global art scene. This is their journey.

1

In 2004, law student Maksym Voloshyn asked Yuliia out on their first date to a museum in Kyiv. Beyond their mutual attraction, they quickly discovered a shared passion for art. Maksym and Yuliia dreamed of opening a gallery of their own. Maksym was trading antiques at the time, and with his earnings, he bought a basement space at 13 Tereshchenkivska Street. In 2006, the Voloshyns turned that space into their first gallery, Mystetska Zbirka, and got married that same year. They were just 21.

The Voloshyns’ mornings were spent in university lectures, in afternoons and evenings, they were busy renovating their gallery space by hand. They wanted to create a unique art space, something Kyiv was missing—a modern, dynamic art venue. Yuliia recalls that they launched the gallery entirely with their own funds and without any experience in the field. They didn’t even know where to start. At first, few visitors came but the numbers were low, but colleagues from the art community guided them on how to promote exhibitions properly, build connections and engage an audience.

At first, the Voloshyns focused on academic art and socialist realism. They learned a lot taking masterclasses from experts and restorers, studying art history, learning to authenticate artworks, studying art history, and analyzing styles and painting techniques.

Within a few years, they had become prominent figures in Kyiv’s art scene. Two museum-level exhibitions played a key role in this rise—“Landscape in Ukrainian Art» and «Still Life in Ukrainian Art.» Each ran for an entire year, drawing over 200 visitors daily to their modest gallery space.

Mystetska Zbirka quickly attracted a loyal base of buyers and collectors, allowing the Voloshyns to start selling artworks regularly. Every cent they earned went straight back into the business. Aside from them, the gallery had only one manager. Maksym took charge of legal matters, client relations, and negotiations, while Yuliia, with her background in economics, managed the finances, crafted exhibition concepts, and worked with the media. The Voloshyns spent nearly all their time at the gallery, fully dedicating themselves to its growth.

Following the 2008 economic crisis, Ukraine saw a surge of interest in contemporary art. The Voloshyns turned their attention to it as well. Compared to classical art, it was more affordable—but visually, it was bolder, fresher, and more dynamic.

«Why water a tree that has already grown? It’s far more exciting to plant a seedling and watch it flourish», they say.

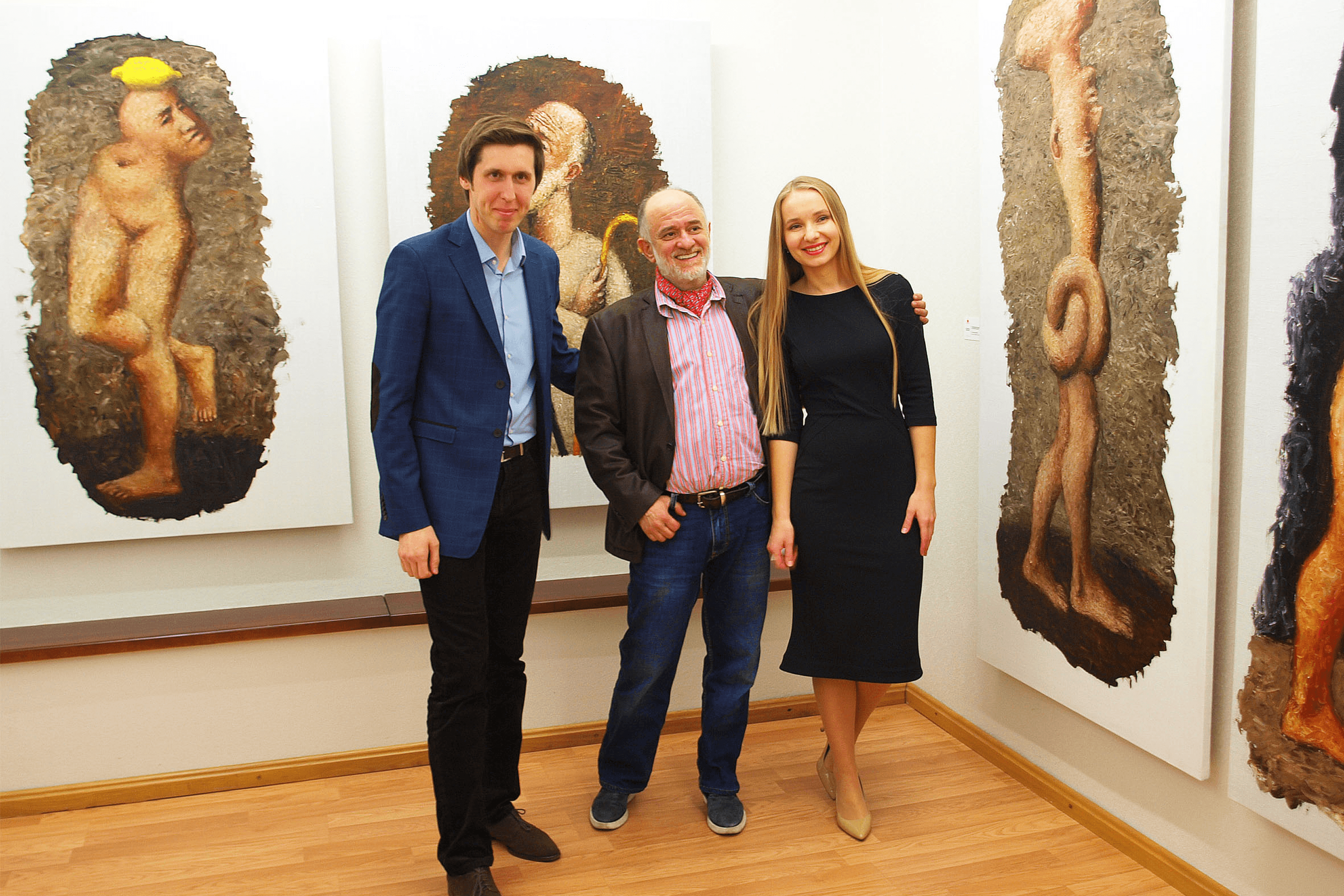

The gallerist couple played a key role in launching the career of at least one major art talent, Mykhailo Deyak, whose works made it to the prestigious Phillips auction house in London. In December 2013, his painting «Doctor Iron Fist» was auctioned off for £8,125. Following his success, the Voloshyns introduced other artists to the scene, including Anna Valiieva and Maria Sulymenko, with whom they continue to collaborate to this day.

The Voloshyns had an ambition to establish a Ukrainian Museum of Contemporary Art on Tereshchenkivska Street, transforming it into a true centre for the arts. «We were deeply inspired by how entire [formerly industrial] neighbourhoods abroad have been revitalized by the art scene, ” says Maksym. „Chelsea in New York, the Wynwood Art District in Miami—these places didn’t just become cultural hubs; they reshaped real estate markets and turned into global attractions. We wanted to see something similar happen in Ukraine. And I have no doubt—it will.»

In 2016, Yuliia and Maksym decided to rebrand. Once again, they renovated the space themselves, invested in high-end lighting, and renamed their gallery Voloshyn Gallery. Maksym explains that even then, they had set their sights on promoting Ukrainian art internationally, with the long-term goal of opening a gallery abroad. In the West, many galleries are named after their founders. When an art space carries the owner’s name, it adds a sense of exclusivity and prestige.

The Voloshyns believe they have never seen themselves as competitors and from the very start, they’ve worked as a team, balancing each other’s strengths. «Maksym is persistent and works well under pressure. He’s passionate and determined. I’m more measured, disciplined, and strategic, ” Yuliia explains. „Spending so much time together—both at home and at work—isn’t always easy. But we share the same vision, the same values, and the same goals. And honestly, with time, it only gets more exciting.“ For them, the gallery isn’t just a business, it’s their way of life.

2

In 2016, Voloshyn Gallery debuted at Scope Miami Beach, one of the world’s leading art fairs. Art fairs are global marketplaces where galleries connect with collectors, museums, and buyers. They don’t just reflect the art market, they shape it, setting trends and influencing the value of artworks worldwide.

Getting into an art fair like this isn’t easy. To be accepted, a gallery must present artists who are both market-relevant and in demand. Their works need to be innovative, and the overall concept must fit the fair’s format. On top of that, participation comes at a price which can reach tens of thousands of dollars. The more prestigious the fair, the tougher the competition. Leading fairs like Art Basel, Frieze, and TEFAF handpick only the most influential galleries in the world. Each year, international art fairs account for nearly a quarter of global art sales—around $16 billion. The Voloshyns acknowledge that participation always carries financial risk. However, the benefits are significant, as participation greatly enhances a gallery’s prestige and global recognition.

In January 2018, the Voloshyns enrolled in a Sotheby’s Institute of Art course in London on art management. Just two months later, in March 2018, Voloshyn Gallery made its debut at VOLTA New York, a prestigious fair dedicated to solo artist presentations. Their booth, showcasing the works of Mykhailo Deyak, was shortlisted among the top ten exhibitions at VOLTA.

3

Since opening their gallery, Yuliia and Maksym had traveled extensively but never considered leaving Ukraine for good. By 2020, however, their growing presence in art exhibitions worldwide meant they were spending more time in the U.S. than in Kyiv. In January 2020, their daughter Daniella was born in Miami, and the family decided to stay in the U.S. for the time being.

In 2021, Maksym and Yuliia made history by organizing an exhibition in Guadalajara and becoming the first to present Ukrainian artists in Mexico since Ukraine gained independence. That same year, they also participated in one of the largest art fairs in the U.S.—the Dallas Art Fair.

Just months before the full-scale invasion, the Voloshyns arrived in Miami to showcase their work at the NADA and Untitled Art fairs. But they both caught COVID-19 and their trip unexpectedly had to stretch their stay in the city. They decided to make the most of their time and curated what would turn out to be a prophetic pop-up exhibition in Allapattah, highlighting how the war that began in 2014 had shaped Ukrainian identity.

«On February 23, we went for a walk in Palm Beach, ” Yuliia talks about the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion. «By then, talk of war was everywhere. I posted a photo on Instagram with a caption: ‘It’s so quiet and peaceful here, but in Ukraine, people are afraid to fall asleep.’» «At 5 a.m. Kyiv time, I noticed my mom and all my friends were online. I checked the news—and saw the first reports of explosions in Kyiv. A wave of cold ran through me, my hands were shaking. For the next few nights, Maksym and I barely slept. We stayed glued to our phones, checking in on friends and loved ones. That’s when we knew—our role as gallerists had never been more important. We had to do everything in our power to make sure Ukrainian art remained seen and recognized by the world.»

In February 2022, the Voloshyns turned their Kyiv gallery into a bomb shelter for an entire year—a role it had played once before, during World War II. The gallery opened its doors to anyone in the neighbourhood who needed shelter. It was warm, had internet access, and provided a safe place to sleep. People slept on mattresses, cooked meals at home and brought them to share.

Meanwhile, Yuliia and Maksym were in the U.S., they organized charity events in support of Ukraine. They raised funds and collected mobile phones for Ukrainians in need. The overwhelming generosity of the local community led them to a decision to establish a permanent gallery space in Miami.

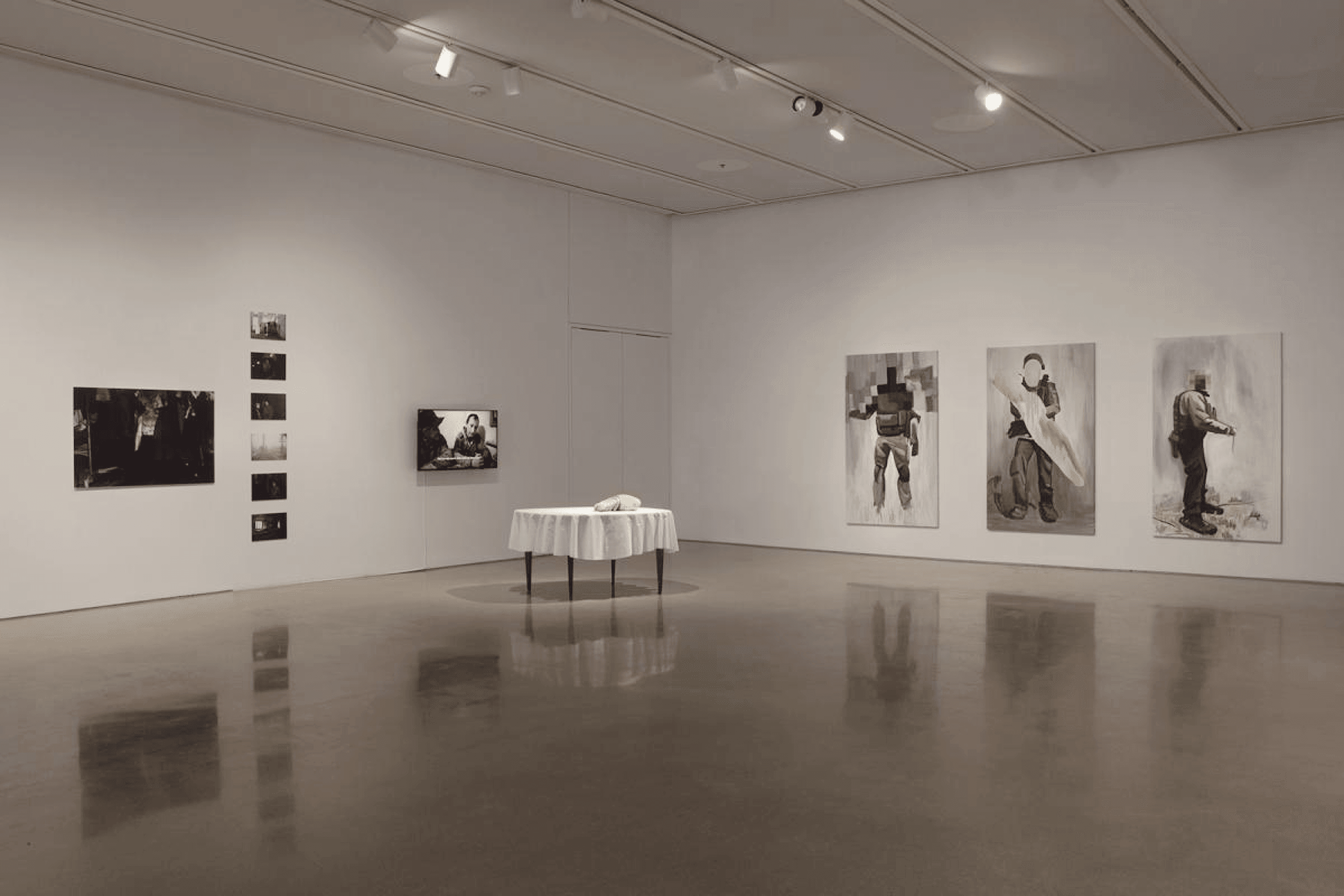

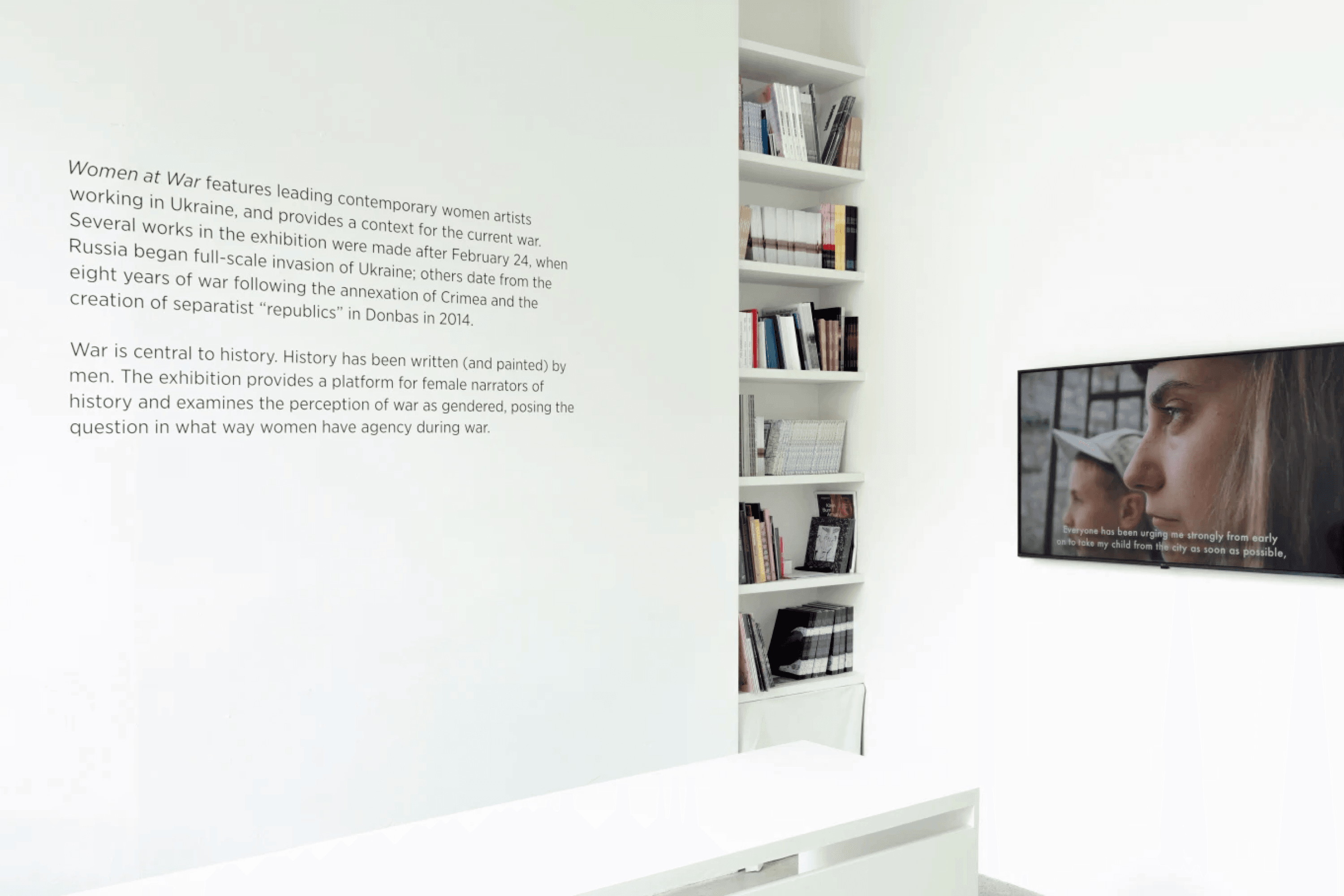

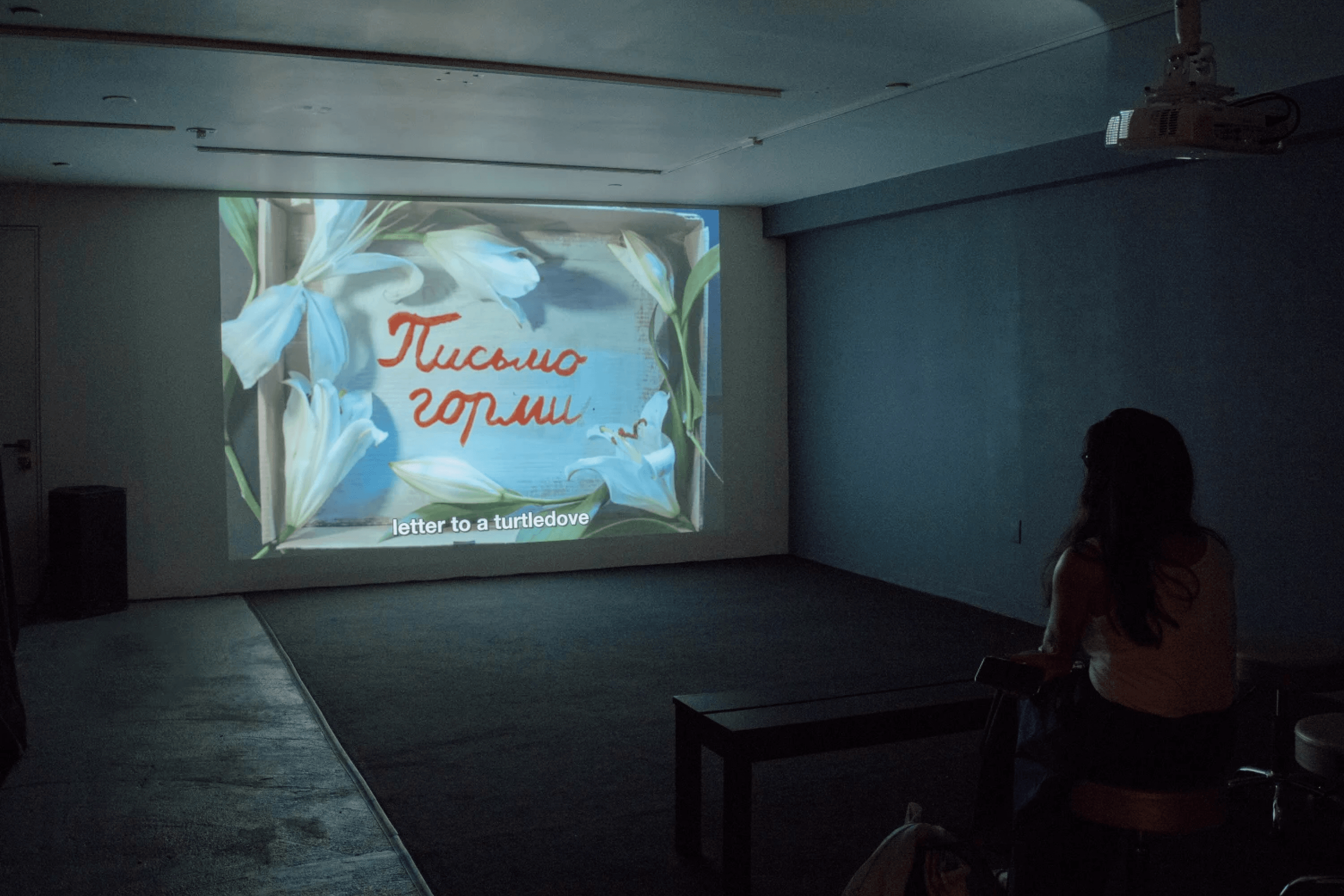

In August 2022, the Voloshyns partnered with Fridman Gallery (New York) to present «Women at War,» an exhibition curated by Monika Fabijanska. The project gained major international recognition, ranking among the top ten exhibitions in the U.S. according to Frieze and earning a spot in The Washington Post’s list of the ten best art projects of the year.

The Women at War exhibition showcased works created at different points in Ukraine’s history—some in response to the full-scale invasion of 2022, others reflecting the war that began in 2014.

In «Strawberry Andriivna» (2014–2019), artist Alevtina Kakhidze recorded phone conversations with her mother, who was trapped in occupied Donbas. Her mother could only call from a cemetery, as it was the only place with cell service.

Photographer Yevgenia Belorusets documented the resilience of female coal miners in Donbas in her series «Victories of the Vanquished» (2014–2017). Despite the war and the harsh conditions of their work, these women retained their humanity—smiling, joking, and simply living.

Dana Kavelina explores the female body as a battlefield. In her drawing series «Communications: Exit to the Blind Zone» (2019), one of the images depicts a fetus strangled by a red umbilical cord, symbolizing loss and trauma.

Zhanna Kadyrova’s sculpture «Palianytsia», a stone formation shaped like traditional Ukrainian bread, became a powerful symbol of resistance against Russian occupation.

4

Even before the full-scale invasion, the Voloshyns had already established themselves in the American art world, building experience and professional connections.

«We saw this as more than just a way to survive—it was a chance to do something bigger for Ukrainian art, ” Yuliia recalls. „The guilt was overwhelming. Reading the news from the safety of another country felt unbearable. We lived with that weight for over a year, and eventually, I lost all drive to do anything. But when we decided to open a gallery in the U.S., it became emotionally easier. We finally felt that in this way, we could make a real impact.“

Adapting to life in Miami was challenging. They raised their daughter without a nanny while managing a demanding work schedule. Daniella became a part of their world—attending exhibitions, art fairs, and meetings with curators, artists, and collectors right alongside them. When the full-scale war broke out, they had nothing but two suitcases of summer clothes. They had to start their lives from scratch.

In Miami, the Voloshyns found a space in the Allapattah district, a growing hub for the arts. The area is home to key cultural institutions, including the Rubell Museum, Superblue, El Espacio 23, and the Institute of Contemporary Art. In October 2023, they officially launched their new 1,400-square-foot art space, located next to Andrew Reed Gallery. They relocated their gallery and their family there, settling in with their young daughter. Just like in Kyiv, they did everything on their own. For the first six months, they ran the gallery without even a single manager.

The gallery opened with the exhibition «No Grey Zones, ” which explored the consequences of wars and political manipulation. Featuring artists from around the world, the show explored aggression hidden behind diplomatic language.

Bojan Stojičić from Sarajevo, a city devastated by the Yugoslav Wars, addressed the Dayton Agreement in his work «Hotel Hope Phantom,» reflecting on the treaty that ended the Balkan wars but left lasting scars.

Ukrainian artist Mykola Ridnyi turned concrete models of bomb shelters into powerful symbols of resilience and defiance.

Israeli artist Dana Levy, in her «Erasing The Green, ” examined how swiftly the borders between Israel and the occupied territories had blurred over time.

The Voloshyns say their Miami gallery is meant to foster dialogue between Ukraine, Eastern Europe, Latin America, and the U.S. They believe that integrating Ukrainian art into the local cultural context is essential for its recognition and growth.

5

On April 14, 2023, the Voloshyns’ gallery in Kyiv reopened with the exhibition «Camera Obscura.» The project featured artists from Ukraine and Eastern Europe and explored themes of violence, fear, and human dignity through the lens of Ukraine’s wartime reality. It emphasized the significance of photography as a tool for documentation and as a means of preserving and reinterpreting collective memory.

Despite the war, the gallery remains active in Kyiv. A dedicated team handles administrative tasks coordinates exhibitions and keeps programs running. Meanwhile, Yuliia and Maksym remain actively involved in all aspects of the work. Running a gallery remotely during wartime requires constant communication. They must account for safety concerns, limited access to resources, and logistical challenges.

«Most of our work is done remotely, with the support of our director and team members in Kyiv. Their resilience and dedication have been crucial in keeping our mission alive.»

Before 2022, the Voloshyns say, Ukrainian art was often perceived as marginal and exotic, existing on the periphery of the global art world. Without strong institutional backing on the international stage, it struggled to gain recognition in mainstream discourse.

Today, Ukrainian art has become a powerful and urgent voice in the global cultural conversation. This transformation has opened doors for artists while placing a new weight of responsibility on their shoulders. Through symbolism and allegory, they tell the story of war—a narrative that prestigious international museums are eager to include in their collections, ensuring that this moment in history is remembered.

The Voloshyns are convinced that Ukraine must actively invest in the global promotion of its art. Ukrainian artists need a strong international presence to ensure their work becomes an integral part of the global art world. Only through international visibility can it naturally gain value, without relying on artificial market strategies or manipulative schemes.

However, Maksym acknowledges that the constant stream of news has left Americans feeling overwhelmed and disengaged. What resonates with the public now are personal stories from artists rather than just geopolitical global events. For instance, the exhibition «The Radial Bone» by Nikita Kadan at Voloshyn Gallery in Miami blended conceptual art with deeply personal accounts from Ukrainians. The exhibition was recognized as one of Miami’s top 10 exhibitions of 2024, according to the Miami New Times.

The Voloshyns knew that basing their gallery’s strategy solely on political narratives wouldn’t be enough. Instead, they took a broader approach—inviting leading curators like Gina Moreno and Omar López-Chahoud, incorporating Latin American art into Ukrainian projects, and forging meaningful connections between Eastern Europe, the U.S., and Latin America. This strategy didn’t just amplify global interest in Ukrainian art—it elevated its market value. In 2024 alone, they hosted 10 exhibitions in Miami, 6 in Kyiv, and participated in 9 major art fairs worldwide.

«Collectors and artists know that for us, it’s never just about buy-sell transactions. We are developing the market, supporting artists, and helping them grow. If a curator or artist is only in it for the money, we simply walk away, ” says Yuliia.

The Voloshyns don’t see their gallery as American. It remains a Ukrainian gallery that has become part of the American art scene. Maksym and Yuliia also don’t view their move as permanent emigration. Ukraine remains their home, and their work will always be connected to Kyiv. When the war ends, they say, the first thing they’ll do is come to Ukraine.

«Art is a weapon, too. It may not stop a war, but it can speak to the world without words.»